![]()

AIR SUPERIORITY IN WORLD WAR II AND KOREA

Participants—Active Duty Years

Gen. James Ferguson, USAF, Retired—1934-70

Gen. Robert M. Lee, USAF, Retired—1931-66

Gen. William W. Momyer, USAF, Retired—1938-73

Lt. Gen. Elwood R. Quesada, USAF, Retired—1924-51

Dr. Richard H. Kohn, Chief, Office of Air Force History

Kohn: Let me welcome you on behalf of the Air Force and thank you for taking a morning out of your busy schedules to share your experiences with us. The Historical Program selected air superiority as the topic for discussion because it seemed to us to be as vital today as it has been in the past. Air superiority is a primary mission for the Air Force; it is perhaps the single most important prerequisite for all other forms of air warfare and the exploitation of the air environment in warfare. We suspect that in recent times air superiority has been neglected in the spectrum of competing ideas and thinking on strategy, tactics, and air doctrine.

We hope to keep this interview, as much as possible, focused on the years before 1955. We believe the present needs to be informed by the past. As historians we believe the past is the most crucial guide to the future. And we fear that some of those in the present are too confident; perhaps they have not heard enough, or know enough, about the past.

Momyer: I think it’s going to be a little bit difficult to cast it completely within the limitations of 1955. I think you are going to have to range a little bit beyond 1955, it seems to me, if you are going to draw on some of the current experience, without getting in and fighting the Vietnam War per se. But if you are really going to raise some of the fundamental questions about how important air superiority is, and what the meaning of air superiority is, then I think you are going to have to go back and forth in your illustrations. I would suggest that we not necessarily constrict ourselves just to pre 1955 per se.

Kohn: Can we focus it there, General Momyer?

Momyer: I would say start out on the pre-World War II era, particularly with General Quesada and General Lee, as kind of a kickoff to then start drawing on their experiences, particularly in World War II.

Kohn: I think that would be fine.

The Pre-World War II Era

Kohn: Let me begin by asking whether before World War II we thought much about air superiority. The belief in the Air Corps Tactical School{6} was that the airplane could reach the economic and political heart of a nation, thereby defeating that nation, leaping over opposing armies and navies. How was this thought to be possible? How widely was that thinking held? Was there a lack of attention to the question of air superiority, and did that inattention prove difficult once the war began?

Quesada: Well, I will start out, mainly because I am the oldest guy here and was in a remote way involved in that psychology. As you suggest, there was a definite school of thought within what was then the Air Service that they could, with immunity, assert a strategic influence on a conflict. There was almost an ignorant disregard of the requirement of air superiority. It was generally felt, without a hell of a lot of thought being given to it, that if there should occur an air combat, or a defense against the ability to envelop, it would occur at the target. That was the thinking of the time. It might interest you to know who the architects of this thinking were. When I cite them, I do it with a compliment to them; because, where they might have been a little bit wrong in detail, they were in fact very imaginative and very courageous. Of course, everybody knows that Billy Mitchell{7} was a factor in it, but he wasn’t the one who molded air force opinion of the time. People who molded that opinion of the time were basically “Tooey” Spaatz,{8} Gen. Frank Andrews,{9} and Gen. George Kenney.{10} A fellow named Ennis Whitehead{11} was also very active in this. In that group it was almost a fetish. They molded the thinking of enveloping. I don’t mean to be critical, but history has to be remembered and written within the context of its time: what was happening then. There was practically no consideration given to air superiority per se. That came along, I would imagine, around 1937 when air superiority began to creep into the thinking. What was then called the pursuit airplane was generally, as I remember it, considered a defensive weapon that would remain static until called into play to fight. It wasn’t until 1937 and later on that we began to recognize that the enemy would adopt the philosophy that we ourselves had adopted: that is, they would defend. It wasn’t until early World War II that we really began to give serious consideration to the fact that, in order for the strategic effort to be effective, we had to be able to cope with fighting opposing defensive forces over our target. World War II brought that about.

Momyer: How is it, in your judgment, that we lost our air superiority experience from World War I? Look at the dogfights. Dogfights were essentially nothing but combat for control of the air, whether you call it air superiority or not. It came out in World War I, theoretically, with the pursuit airplane. The pursuit airplane was primarily to fight other pursuit airplanes, to shoot down balloons, and to shoot down any kind of reconnaissance activity. There is a gap, it just seems to me as I have looked back through the history, a complete gap, until you get probably almost to the time of Chennault.{12} I don’t think it is really clear—maybe you can amplify that—what Chennault’s concept was of pursuit aviation. If you will look in all the readings about what he said, he kept talking about air defense or defense of the United States in terms of pursuit and talked about bombardment escort. Can you amplify what you think Chennault thought about air superiority at that time?

Quesada: If I had expanded my remarks and thought of Chennault, which I would not have—you reminded me of it—I would have to say that he made a big impact on this problem. Don’t forget that before we were in the war he was on the battleline fighting. He learned through experience that in order for your enveloping force to be effective you had to do something about its air defense. Whether he thought of it as creating a situation over our targets that gave us superiority of the air, I just don’t know. Chennault was the great advocate of pursuit aviation. He carried the ball, and almost boringly so. He was a pain in the ass to a lot of people. He did turn out to be quite right, as many people who are pains in the ass do.

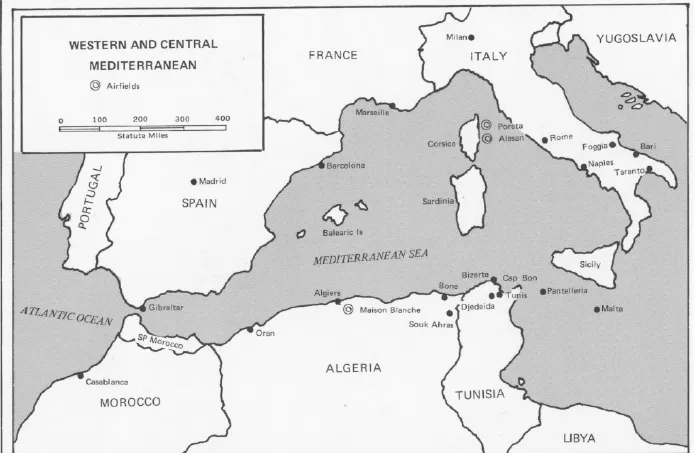

Momyer: Almost in that same pre-world war time period, we had the Spanish Civil War, with the German Condor Legion, and the forces of the Soviet Union.{13} You had really a semistrategic bombing campaign, for example, with the bombing of Madrid and the escort and the fighter engagements that took place there. Yet, looking back, I can’t find much interpretation of that. I can’t find much codification. I guess what I am really coming to is that up to World War II, I can’t find much codification of what we really thought about how we would employ air, except for the strategic forces. You had strategic thinking, of course, with AWPD-1—the war plan—as you well know, for the targeting of Germany.{14} But I guess a theory of air superiority in terms of its relationship to the ground forces was totally missing.

Quesada: Well, “Spike” [General Momyer], I was trying to say, without knowing it, what you have recited. I think during that period, we really didn’t know what we were trying to do. We were doing it but not defining it. Air superiority, or the concept of air superiority was, in my opinion, really defined after the second World War started. In Spain it was used in a sort of half-assed way, but I don’t think it was defined. Let me go back to your comment about World War I. When you look back—really as we think now—the fighter airplane in those days was basically an ego trip. The fighter airplane didn’t do a hell of a lot of good. They would go up and fight each other and create aces, but there was no great strategic effort that was being executed or fulfilled. Basically—I don’t mean it in an unattractive way—the fighter business in those days was a bunch of guys going up and fighting another bunch of guys without a known objective.

Momyer: I think our preoccupation with the strategic concept of war did more to frustrate any thinking on the employment of other aspects of aviation. If you will look at our pre-World War II writing, it’s almost all devoted to the employment of strategic aviation against the heartland of a nation. If one were able to overfly enemy ground forces, overfly his naval forces, and get at the source of his power, one could bring the war to a conclusion without defeating his military forces.

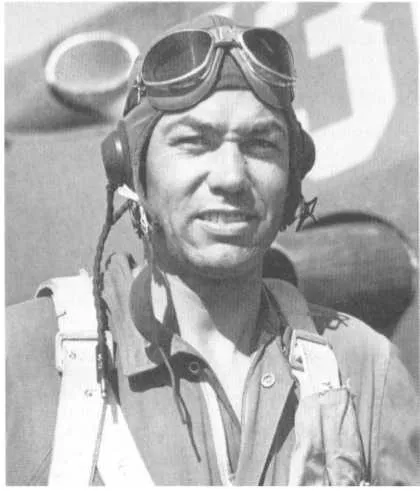

Robert M. Lee, Jr., as a first lieutenant.

![]()

World War II

Kohn: While you have said that there wasn’t a great deal of thought about air superiority and it wasn’t really codified, what kinds of problems did this cause us as we went into World War II? How did you respond to what you found in the air war, once we were in the war? What lessons did you find as you looked in 1939, 1940, and 1941 at the fighting in Europe? Did we change our thinkin...

![Air Superiority In World War II And Korea [Illustrated Edition]](https://img.perlego.com/book-covers/3018633/9781786257536_300_450.webp)