- 143 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

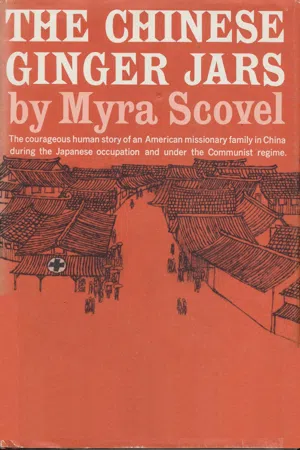

The Chinese Ginger Jars

About this book

The Chinese Ginger Jars is a bright and intimate portrait of the adventures, trials, and achievements of an American housewife who lived through dangerous days in modern China.

When Myra Scovel arrived in Peking in 1930 with her medical missionary husband and infant son, China was a land steeped in an ancient culture, mellow as the smooth cream ivory of its curio shops, relaxed as the curves of a temple roof against the sky. Twenty-one years later—as the Scovels were forced to leave China by the Communists—it was a country of fear, of terror, of hatred toward the foreigner. The dramatic events that transformed China are recounted here from the fresh and poignant viewpoint of an extraordinary American wife and mother.

When Myra Scovel arrived in Peking in 1930 with her medical missionary husband and infant son, China was a land steeped in an ancient culture, mellow as the smooth cream ivory of its curio shops, relaxed as the curves of a temple roof against the sky. Twenty-one years later—as the Scovels were forced to leave China by the Communists—it was a country of fear, of terror, of hatred toward the foreigner. The dramatic events that transformed China are recounted here from the fresh and poignant viewpoint of an extraordinary American wife and mother.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

TWO—THE ANCIENT POEM

“Before my couch, is the light of the effulgent moon.

Perhaps it is hoar frost on the ground.

Raising my head, I gaze at its brightness;

Lowering my head, I think of home.”—Li Po (A.D. 701-762) (Poem on the ginger jars, translated by L. Carrington Goodrich)

In my complacent ignorance I had always pictured China as a warm, sunny country. In spite of the specific instructions from the Board to take plenty of winter clothing to Peking, China was the Orient; and to me, the Orient meant hot weather. Our first Chinese winter furnished another of the enlightening experiences that China was constantly giving me. It was cold, bitter cold. The wind that blew down on Peking from the Gobi Desert felt as if it had been swept across Arctic ice. And seeing red lacquer temples and green pagodas through a whirling snowstorm was like living in a mixed-up dream. Fred finally bought a ponyskin coat for me from a Mongolian peddler. The Chinese teachers had their long garments lined with fur, but most of the populace kept warm by donning layer after layer of padded trousers and coats. Their clothing was so bulky that if a child fell over, he couldn’t get to his feet and someone had to come and pick him up. I understood now why the pastor of the church had told me that the seating capacity of the pews was ten in summer and eight in winter.

The winter passed swiftly, though, for we were very busy. We worked many hours a day at language school and at home. Until we could communicate with the Chinese in their own tongue, we could not begin the work which we had come so far to do. Our mission considered language study of primary importance. No matter how much Fred fretted and complained that his medicine was getting rusty and he must see some patients, there stood the inexorable rule that two years of language had to be passed before he could take on the responsibilities of the hospital. He was to be thankful for that rule in the years to come. I was given a little more leeway as to time, but we both had to pass five years of language study before we could be voted back after our first furlough.

So we kept at it, that first winter in Peking, and at last our diligence began to bear results. We practiced on anyone who would talk to us. We were still far from thinking in Chinese, but we could understand a little and we could, by repeated efforts on our part and an uncanny perception on the part of the Chinese, make ourselves understood.

Emboldened, I set out to learn another skill without which I had been told one could not get along in China: bargaining. One day in November as Fred and I were walking about the temple fair, I had spotted an incense burner, a tall pagoda-like brass piece about ten inches high—a hideous thing, I was to learn later; but being new to the beauty of simple bronze, I thought it was typically Chinese and I wanted it badly.

The shopkeeper was immediately aware of my interest. After the usual exchange of greetings, I ventured to ask in my classroom Chinese, “To shao ch’ien?” “How much, how little money?”

“The price is fifty dollars,” said the shopkeeper, rubbing the brass with the sleeve of his faded coat. “But you have just arrived in our country and I want you to have this, so I will give it to you for forty dollars.”

Um, not bad, I thought. Exchange is almost five to one. Less than nine dollars our money. But I mustn’t forget this bargaining business. I’ll begin ridiculously low.

“That is very kind of you,” I said, “but I really cannot spend more than ten of your dollars for an incense burner.”

“I am very sorry, T’ai T’ai,” he replied. (“T’ai T’ai” meant “Honorable Mrs.”)

He put the incense burner back on his improvised shelf, a board on two packing boxes, and smiled sadly. Round One was finished and we retired to our corners.

Many times that winter I was tempted to meet the price of my smiling, innocent-faced shopkeeper as he went from forty to thirty-five, to thirty, to twenty-five. I could hardly resist as his smile disappeared and his eyes grew sad. I would look from the lengthening face of the shopkeeper to the stern face of my husband and come away each week without my incense burner.

Then suddenly it was blazing spring. The Orient with its heat quickly redeemed itself. Within a week we were to leave Peking and continue language study at the cool seaside village of Peitaiho, northwest of Peking. We were eager to get to our first mission station, Tsining, but the missionaries there had written that on no account were we to bring First-Born into the heat of the Shantung Plain before September. In the midst of the packing, I remembered the incense burner and dropped everything for one last round with my shopkeeper. Fred came along to pick up some old coins he had seen at another shop.

“We are leaving Peking, as you know,” I began. “Do let me have the brass piece for ten dollars.”

“Yes, you are leaving,” he replied, “and though I cannot afford it, I will give you the incense burner for ten dollars. It will mean that my old mother and the children will have to go without food today, but I want you to have it. Though I lose money, I want you to have it.” He actually brushed away a tear with the back of his hand. For the fraction of an instant I wavered, but I did not lose the fight. Fred, who’d been off buying the coins, came up in time to rejoice with me that, for once, I had stood my ground when left on my own.

As we were leaving the temple grounds, on an impulse I ran back to the shopkeeper. “You and I have had an interesting winter of bargaining,” I said. “I am new to your country, as you have said, but I am going to be here a long time. I want to learn how to bargain properly. Tell me, how much did you really pay for this incense burner in the first place?”

The shopkeeper laughed and said indulgently, “Just three dollars. Good-by, T’ai T’ai. I lu ping an—all the way, peace.”

We had a glorious summer at Peitaiho, aside from Fred’s swimming miles and scaring me to death by staying out of sight for hours. There were sharks off the coast. Sometimes I would be so furious that I’d wish they’d bite him; then I’d be so frightened at the thought that I would walk out into the sea as far as I could just to be that much nearer to him. I dared not swim out for fear of the sharks. He could never understand why I worried. He could swim, couldn’t he? Cramps? Nobody ever had a cramp who used his head. And he loved the ocean and the gulls and the feeling of being alone in creation.

First-Born added a few words to his vocabulary and learned to walk by digging his fat toes into the wet sand of the beach. He was so fat that his little mouth was lost in a hole in his face. The Chinese thought that anyone who was fat was beautiful. I took it rather badly the first time a friend tried to compliment me by saying, “Teacher-mother, how fat you are!” The only thing that troubled our Chinese friends was that the baby had blue eyes. Once when some country women were watching me bathe him, one of them said to the other, “She’ll kill that child, washing him so much. How beautiful he is! So fat, so pretty, so white. If only he didn’t have those goat’s eyes.”

At last the day came when the train puffed into the Tsining railway station. What a welcome we had from our fellow missionaries, the Eameses and the D’Olives and the Walters, Miss Stewart and Miss Christman; and from the Baptist friends who lived across the city—the Connelys, Miss Smith, Miss Frank and Miss Lawton. They were all at the station to meet us. Their first words were prophetic of what our life in China was to be.

“The city was taken over by bandits last night,” Frank Connely said casually, picking up a suitcase and maneuvering me through the crowd.

“Bandits!” I gasped.

Our senior missionary, the Rev. Charles Eames, who was hurrying along behind us, stepped up to the rescue.

“There is nothing to worry about,” he said quietly. “Shops will be looted; there may even be some shooting, but life for us will go on as usual. Really, there is nothing to worry about.”

Maybe we should get right back on that train, I thought. Fred looked as if he were enjoying the excitement. Just the kind of an adventure he’d looked forward to, I could read behind his twinkle.

But the streets were quiet as we drove through them in our cavalcade of rickshaws. In Peking I had been surprised to find that all Chinese houses were behind walls. Here, too, the streets were lined with mud or brick walls; closed doorways with scrolls of letters across their tops and down each side marked the entrance to a private courtyard. For that matter, our compound was walled and the spacious grounds of each of our homes were surrounded by another set of walls. We did have access to one another through a path that ran along the back of the compound—an arrangement that was to stand us in good stead in the years to come when it was too dangerous for us to be on the street.

We stopped first at the Eames house where we were served tea. I was impatient to see our home. And what a surprise I got when I saw it! The thatched-roofed hut of my imagination turned out to be an imposing structure of gray brick that looked like a small factory with a front porch. Our house had been the one most recently built. The other houses on the compound were more in keeping with their Chinese background, with lattices of Chinese design and pillars on the porches. There had been an outcry when the first two-story building went up, many years ago; it would be possible for foreigners to look down from a point of vantage into the courtyards below. But by the time we arrived, a few of the more progressive Chinese inside the city wall were building two-and three-story houses themselves.

Fred picked me up in his arms, carried me across the threshold of our new home, dumped me in the front hall among the luggage and was off to see the hospital.

The house looked huge after our two small rooms at the language school. We had a living room, a dining room, a kitchen and a study on the first floor, and three large bedrooms and a small one on the second. There was a third floor that could be finished off if we ever needed it.

“We’ll never get this much furnished,” I told Fred that evening as we sat in borrowed chairs before our own fireplace. “Mrs. D’Olive said something about furniture made at a model prison. Somewhere in these trunks I have a furniture catalogue. We can show them pictures of what we want. I’ll fish it out and we can have a couch and a chair made to begin with.”

“I’m glad we brought our own beds, even though the freight was so terrific. And we’re lucky to pick up the dining-room furniture that belonged to that couple who’ve gone home. What were their names?”

“I didn’t get it.”

“Well, honey, there’s one room you won’t have to worry about furniture for—our goldfish bowl of a bathroom; doors in three of the walls and a window off a porch on the fourth! Did you find out what time of day the man comes to empty the can?”

(The can arrangement didn’t last long. While walking along the Grand Canal one day we discovered a house deserted by the Standard Oil Company when the last foreign resident left. Fred climbed to an upstairs veranda and saw through the window that there was a good bathroom in the house. He wrote at once to the office in Shanghai for permission to buy the outfit complete with pipes. He installed it himself and designed the septic tank from one of his medical books on sanitation.)

“Now tell me all about the hospital,” I said as we drank our bedtime coffee.

“There’s too much to tell and you’re tired. I’ll take you over and show it all to you the first thing in the morning.”

That night when I got up to cover the baby—and for months afterward—I looked down the stair well to see if one of those bandits had broken into the house and was even now on his way upstairs.

Right after breakfast next morning we walked the half block and crossed the road to the hospital. Could it be called a hospital? The wards were rows of mud huts; the beds were boards on trestles. There was, however, a good little operating room in a small brick building which also housed the outpatient department. I fell in love with the little room that was the pharmacy. The shelves were filled with beautifully painted porcelain jars. I found it difficult to believe that they held such modern and prosaic things as zinc ointment and unguentine. I felt that if I lifted lids I would find tiger claws, lizard skins, and scorpion tails.

The operating room was across an open courtyard from the wards.

“What do you do with postoperative cases in the dead of winter?” Fred asked the immaculate operating-room supervisor.

“We just wheel them across to the ward on a stretcher and pray that they won’t get pneumonia,” he replied. (There were no antibiotics.) This was only one of the reasons why, some time later, we converted a well-built school building into a very usable sixty-bed hospital.

We got a language teacher at once, for Fred was determined to complete his second year by January so that he could take over full responsibility for the hospital. He was allowed to take a clinic for only an hour a day and the rest of the time had to be devoted to language study. Adopted Uncle Eames, being a minister, would be delighted if Fred could relieve him in time for the spring itineration trips to the country Christians...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- THE PROLOGUE-THE GINGER JARS

- ONE-THE JADE PAGODA

- TWO-THE ANCIENT POEM

- THREE-THE GOURD

- FOUR-THE GRAPE

- FIVE-THE CHRYSANTHEMUM

- SIX-THE PEACH

- SEVEN-LAO SHOU HSING, THE BIRTHDAY FAIRY

- EIGHT-THE MEI HUA (FLOWERING PLUM)

- NINE-THE BAMBOO

- THE EPILOGUE

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Chinese Ginger Jars by Myra Scovel,Nelle Keys Bell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Central Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.