- 242 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

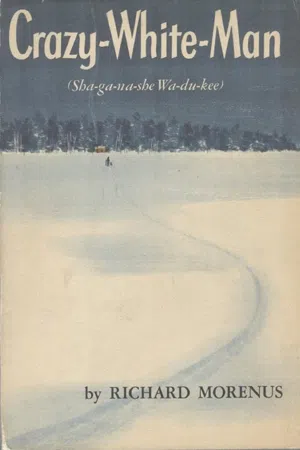

Crazy-White-Man (Sha-ga-na-she Wa-du-kee)

About this book

The author was a businessman from New York who got tired of the "Big City" life and was unhappy for some time. He decided to move as far away from that environment. Taking only his dog, some gear, and an open heart he travelled to Canada. During this trip, he found an island of epic beauty and decided to purchase it. His story tells of his difficulty trying to adapt to such the harsh environment. The local population were Native Americans who gave him the name "Crazy White Man" for making the changes that he did.

Dick Morenus, New York radio and magazine writer, took to the Ontario bush country to shed his ulcers. After writing this hilarious account of his six-year transition from tenderfoot to woodsman-guide, he returned to city life to teach, write, and lecture,

CHICAGO TRIBUNE — "As a story of the indomitable spirit of men and women pitted against the overwhelming forces of nature, 'Crazy-White-Man' is an inspiring one; as a tale of pure adventure, it will be hard to put down ... a book that is a little classic of the rugged life."

CHRISTIAN SCIENCE MONITOR — " ... one of the best tales of escape from city pressures ... It is a vivid close-up of the Ontario bush—written down with the vividness and gaiety of a man who knew he was free."

NEW YORK TIMES — "Respect for Mr. Morenus' courage and hardihood grows with every page we read . . . it emerges as a valuable addition to the small number of books about the Canadian bush."

COLORADO SPRINGS FREE PRESS — "Anyone from young to old who has wanted to toss the soft life of today into the discard and live as our ancestors did will enjoy this book. To those who have lived under frontier conditions it will be equally refreshing—and that cannot be said for many of this type."

Dick Morenus, New York radio and magazine writer, took to the Ontario bush country to shed his ulcers. After writing this hilarious account of his six-year transition from tenderfoot to woodsman-guide, he returned to city life to teach, write, and lecture,

CHICAGO TRIBUNE — "As a story of the indomitable spirit of men and women pitted against the overwhelming forces of nature, 'Crazy-White-Man' is an inspiring one; as a tale of pure adventure, it will be hard to put down ... a book that is a little classic of the rugged life."

CHRISTIAN SCIENCE MONITOR — " ... one of the best tales of escape from city pressures ... It is a vivid close-up of the Ontario bush—written down with the vividness and gaiety of a man who knew he was free."

NEW YORK TIMES — "Respect for Mr. Morenus' courage and hardihood grows with every page we read . . . it emerges as a valuable addition to the small number of books about the Canadian bush."

COLORADO SPRINGS FREE PRESS — "Anyone from young to old who has wanted to toss the soft life of today into the discard and live as our ancestors did will enjoy this book. To those who have lived under frontier conditions it will be equally refreshing—and that cannot be said for many of this type."

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

THE DEEP FREEZE

I AWOKE THE following morning to 10º above, and again I tested the ice. This time it held my weight—that is, it held it until I ventured twenty or twenty-five feet out from shore. A warning crack sent me slipping back to safety, for twenty feet offshore there was about twenty feet of water under me, and at that temperature I hadn’t the slightest desire to be dunked. But ice was making fast, and if the cold weather held there should be safe ice within a few days.

That morning I had to use an ax to chop through the ice to fill my water pails. One thing I noticed that second day of freeze-up, although it didn’t make for much of an impression at the moment, was that my woodpile didn’t look quite so large and secure as it had before the weather turned cold. It was surprising how much wood a stove could eat when cold weather whetted its appetite.

By ten o’clock in the morning the cabin had warmed up to a comfortable 65º, and at last I felt I had the design of my winter living worked out. Up in the morning to fix the fire and breakfast; get a couple of pails of water; load the box on the porch from the woodpile for convenience—then I’d be all set to devote the rest of the day to my writing. I’d have practically all day to write. So that problem was solved. In fact, that second day of freeze-up I worked on a couple of radio plots and laid out a magazine article I intended to do. At last life was taking on a proper pattern.

That night there were new sounds to break the winter silence. They sounded like fusillades of rifle fire. I opened the door of the cabin and stepped out onto the porch. I was slapped in the face with more frigid air than I had ever felt before in all my life. Nik had come along and, when he whiffed the cold, he sneezed and ran back, headed for the stove. It was too cold to stand there without a jacket, so I went back for my mackinaw and a stocking cap, because I still wanted to know what was making the noise. I also brought a flashlight and looked at the porch thermometer. It showed 20º below zero. The snapping and cracking were coming from the trees. The sap was freezing. As I stood there and listened, I could have composed several very unfunny puns about myself.... about sap and freezing. When I went back into the cabin, a swirl of vapor followed me and rolled across the floor.

The next day was cloudy but the cold weather held, and that morning I chopped through about an inch and a half of good solid ice to get water. It was while I was filling my water pails that I heard a hollow-sounding rhythmic tapping, and suddenly Nik began to bark. I looked at him and then turned to look in the direction his nose was pointing and saw the Indian. He was close to the shore across the channel. He was headed east. The tapping was caused by a heavy pole he held in one hand. He walked slowly, pounding the ice with the pole ahead of every step. I couldn’t recognize him at that distance, so I didn’t know whether it was an Indian I had seen before or not. But out of sheer neighborliness I yelled, “Hello,” and got no reply. I waved and that went unanswered, so we each went on minding our own business.

From what I had already learned about Indians I knew that they are the best gamblers in the world. They will bet only on a sure thing. Therefore, I knew that this Indian, whoever he might be, would never under any circumstances have put one foot on ice unless he was certain there wasn’t the slightest chance of his not reaching his destination safely.

This Indian gave me an idea. This would be a good day to get my deer. It was only a quarter of a mile across the channel to the bush, and if an Indian would take a chance on the ice being safe, it was a cinch that I could get across. So I loaded up the stove, shut the drafts, and took my rifle down from the wall pegs. I used a Winchester Model 94, .30-30. This rifle is a little light for big game, but with 185-grain bullets and with every bush shot being short this carbine has impact enough to bring down any game in the bush properly hit—moose, deer, bear.

It was a strange sensation crossing that ice. I figured that the channel ice, under which the water was very deep with a fairly strong current, might not be so thick or so safe as the ice nearer shore. Added to this was the fact that the ice was as clear as glass and I could see through it to the lake bottom. This was more or less interesting until the bottom went out of sight. That was a bit disturbing and created a feeling perhaps like being suspended in air. But because of this I went that Indian one better in being cautious.

I cut a poplar pole about twenty feet long and trimmed it. Then I took the heaviest ax I had. I slung my gun over my shoulder and held the pole under my arm. If I went through the ice, my weight would be distributed over the length of the pole and I could probably get out. Then with the ax in my other hand I crawled out onto the ice and pounded hard with the flat of the ax as far ahead as I could reach. If the ax head didn’t go through or the ice crack, I knew it was safe to move ahead. I got across without event but, as I looked back at the island, I wondered if it had been a wise thing to do. It was a long quarter of a mile. But I counted on that Indian. I knew he wouldn’t take a chance.

As I stood there on the shore looking back across the channel, I said, “That’s the trouble with people like me.” Just because I’d seen an Indian walking along the shore, all at once I had to do a lot of things. It wouldn’t have made the least bit of difference if I’d waited another day, or a week, before going hunting for my deer. I didn’t actually need it then. Furthermore, I had gone ahead without planning and without any thought.

There I stood on the bush side of the channel. Suppose suddenly the sun should come out hot and warm and start thawing, and a wind come up. There I’d be then with open water between me and the island, and thousands of miles of bush behind me. At least that Indian had a destination that was as safe for him as the point he’d left or he never would have started. But not me. I had to be smart. And certainly not the know-how smart. All I could do was pray for still cold weather and clouds. That I did and then turned into the bush to see if I could find a deer that was dumber than I was.

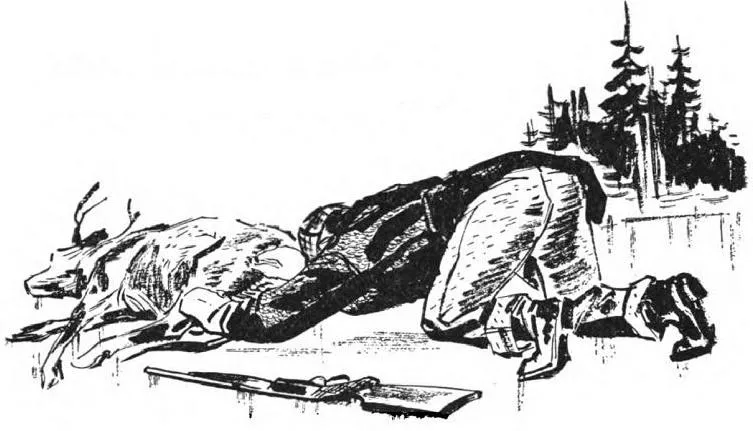

I hadn’t gone a hundred yards before I saw a young buck. So in less than an hour after I’d left the island, I had my deer and was ready to go back. There was no change in the looks of the ice, but the cabin with the pencil of gray smoke coming out of the chimney pipe looked a long way off. I had the deer on the ice and was ready to start across. On my feet I was wearing leather-topped rubbers. I tried to walk and pull the deer behind me, but my feet went out from under me. I got behind the carcass and tried to push, and it was as if I’d been on roller skates. I tried pushing and prying with the poplar pole. I slid all over the place on that glassy ice, but the deer didn’t budge an inch.

The deer, eviscerated, weighed probably 100 to 125 pounds. Suppose, when I reached the middle of the channel, this weight added to mine would be too much for the ice to hold? When I thought of this possibility, I was glad the deer hadn’t moved. There must be a safer way to get my meat home.

I had no intention of leaving all that meat there for animals to eat and going home without it, nor did I have the slightest idea how I was going to get it across over the ice. Then again a course in high-school physics came to my aid. I went back across the channel to the island. I had a very small canvas-covered cedar canoe that weighed about thirty-five pounds. I got this canoe out of storage and put it on the ice. I tied about a thirty-foot length of rope onto it and crawled back again to the deer, pulling the canoe after me. Then I skinned the deer to have less weight to pull and put the meat into the canoe.

The canoe, resting mainly on its keel and one side, presented less friction against the ice. This time in going across I sat down and backed over. In that position I presented more friction, or traction, than did the canoe. I hunkered backward, moving the canoe by pulling the rope as gently as I could a foot or two at a time. Separated by the length of rope this kept our weights a safe distance apart. If I pulled too fast or too hard, the canoe stood still and I slid. Once, about midway across, I stopped and looked around and was thankful there was no one to see how silly I must have looked, sitting there on the ice pulling what appeared to be an empty canoe at the end of a rope. But bit by bit I finally got across. I was awful cold from sitting down, but it was worth it. That night I had butchered venison curing in the store shed.

That evening after supper I took Nik down to the shore to explain to him the superior advantages of an education. I showed him where the deer was hanging, to exhibit my hunting prowess, and told him of my experiences of that day. I’m sure he was duly impressed. One wonderful thing about Nik, he was a consummate diplomat; he never let me know that there were moments when he might have thought I was slightly out of my mind. Little flakes of snow were in the air when we went back to the cabin, and it didn’t seem quite so cold. There was also a bit of breeze in the making.

The wind came up fast, driving out of the north, and within an hour or so it had risen to a high-pitched whine, slashing a blizzard ahead of it. Snow was driving against the north-side window. This was more like what I had expected the north to show in the way of winter theatrics. I wanted to feel the storm. I wanted to see if these blizzards of the north warranted the adjectives and descriptions I had read and heard about them. I buttoned and zippered into my heaviest clothes and stepped outside.

It would be difficult to exaggerate the steady power of the storm. The wind was gale force and had the feel of being solid substance. The snow was not the soft, melting snow of farther south. Each sub-zero, frozen flake stung and burned as it struck flesh. I didn’t leave the cabin porch and I wasn’t outside more than two or three minutes when I’d had enough. There’d been nothing to see. I could only feel and hear the storm. Back inside I found I was slightly out of breath.

I was sure that by morning the blizzard would blow itself out, and winter would be official.... with snow. I went to sleep that night with a thought of gratitude for the protection of my little cabin against the storm.

Morning came and the blizzard with it. It was no stronger nor had it diminished; it was the same blizzard as the night before. This was no Currier and Ives kind of snow, the gently falling flakes of the Christmas-card kind. This snow wasn’t falling; it was coming out of the north and being driven horizontally southward, and I wondered how any of it happened to stay on the ground. It was as if I were looking at the world through a curtain of shimmering scrim. I could barely see the shore trees. The shore across the channel had whitened out.

Getting my pails of water that morning was not the joyous happy experience of the days before. I took a shovel and my pails and first floundered through knee-deep drifts getting from the cabin to the lake. Then, back to the wind, I slipped and skidded through a foot-deep layer of snow until I was far enough out on the lake to have clear water under the ice. I’d thought the day before, when I was getting the deer back to the island, that there was nothing so slippery as rubbers on sheet ice. I was wrong. A foot of snow on top of the ice makes it more slippery.

When I reached the spot where I’d get the water, I began to shovel. Then I knew what it was to shovel snow against a whirlwind. I’d lift a shovelful of snow, and the wind would blow it off the blade and, with the same breath, pile more snow into the spot from which I had just taken the scoopful. At the end of the first hour I’d had enough snow to last me for the rest of my life, but that wasn’t even a fraction of it—there would be seven months more of the stuff. And I was the individual who had been slightly disappointed that the performance of the north country wasn’t living up to its press notices!

Somehow I got water that morning—I’ll probably never know how. In between trips to the cabin to get warm I shoveled and scooped and shoved and scraped to get a space of ice cleared large enough for me to wield the ax to chop open a hole. It took most of the morning to accomplish this, and, no sooner were my buckets filled and my back turned, than the water hole and all around it filled in and leveled even with the rest. The powdery snow had either blown through or sifted into the crevices of my clothes because, when I got back to the cabin and began to thaw out, every stitch I had on was soaking wet. It seemed like a waste of precious water to heat a panful and sponge off in front of the stove.

When I had changed into dry clothes, I sat for a while and watched the storm through the window. I marveled that wind could sustain so even a velocity for so many hours, and I wondered if it would ever stop snowing. Apparently it had no intention of stopping. I had become accustomed to the rains in the summertime which came in two sizes—the three-day rain and the five-day rain—but I had no idea the winter snows followed the same pattern, I found out they did. This first blizzard turned out to be one of the shorter three-day kind. That meant that for three mornings I went through increasingly thicker snow to fill my water pails. I became respectfully conscious of the value of water.

As I sat there watching the storm swirl snow in eddies and form drifts about the cabin, I felt a draft. I looked around. The windows were closed. The door solidly latched. The fire was going well; in fact, both fires were burning, one in the heater and one in the cookstove. Yet a strong current of cold air was coming from somewhere. I followed the breeze back to the north wall and there, between two of the logs close to the floor, located a spot where some of the moss chinking had come loose.

This so-called “reindeer moss” is a spongy lichen that grows indiscriminately throughout the bush wherever there is a rock surface to fasten upon, and that is practically anywhere. It is colorful and has its uses. Among its advantages are that it may be used in place of sawdust as a temporary cover for ice. It does well, dampened, to keep a catch of fish fresh. Indian squaws find it a most practical substitute for diapers. And it is used as chinking between the logs of cabins. Its disadvantage, I found, is that when it dries it turns to powder.

During the summer it had been kept sufficiently moist by the rains to be serviceable as chinking, but the heat from the stoves had dried it out and the force of the storm wind had loosened it. With a screwdriver I tried to jam the moss back into place to plug the hole, but as I touched it the wind whistled through, blowing pulverized moss into the room ahead of it. Those walls that I had thought were so well joined and chinked were as porous as a summer-resort towel. I made temporary repairs with wadded paper and wondered what I could use as permanent chinking.

I sat down and looked at the logs and did some figuring. With 5,280 feet in a mile there was just about a quarter of a mile of crevices between the logs to be rechinked. I got together all the pieces of sacking, burlap, rags, and old blankets that I could find and started to work. I put the typewriter away because I needed the table on which to cut my materials into strips. Then with a hammer and screwdriver I dug out moss and hammered in the rags. My time was pretty well taken up for several days in this pastime. Bat the job was finally done, and by that time it had stopped snowing.

During the storm the temperature had remained near zero. It cleared late one afternoon, and that night it got cold. It was 30º below when I turned out the lamps. As I lay wrapped in my blankets, at first I heard only the comforting crackle of the fire in the heater. Then from outside, as the temperature dropped, came the sporadic rifle-like cracks of the freezing sap in the trees. Then heavy thunderous boomings were added as the thickening ice of the lake cracked open, followed by a high glissando scream like a ricocheting bullet whining along the crack for miles into the distance. Then silence. This was repeated over and over—cannonading and ricochets and rifle fire and silence. And in the silences was the chuckling of the fire.

The next morning I established my permanent water hole. There was no such plac...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- FROM BROADWAY TO THE BUSH

- CONFUSION IN THE PINES

- FRIGID AIR

- THE DEEP FREEZE

- DEFROSTED

- HONEST LIARS

- HOT DOGS ON ICE

- NICHIES

- RAINBOW’S END

- THE SOURDOUGH

- WINDIGO

- DESTINATION: WILDERNESS

- R: LYNX CLAWS AND DRIED BONES

- BUSH BRIDE

- LODED

- BUCHANAN’s DIARY

- WA-BE-GO-SHEESH

- BEAR FACTS

- THE STORY OF ANNA OLSEN

- MEG-WICH AND B’JOU

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Crazy-White-Man (Sha-ga-na-she Wa-du-kee) by Richard Morenus in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.