- 263 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frederic Remington's Own West

About this book

A collection of Frederic Remington's writings, complemented by more than one hundred of his famous drawings, provides an exciting record of the Old West as it once was, with tales of cowboys, Indians, and soldiers.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART ONE—IN THE OLD SOUTHWEST

Frederic Remington knew and loved the whole West, from the arid regions of Arizona Territory to the rolling prairies and rugged Rockies of Montana. In the story of the Old West, the Southwest and the Northern Plains stand out as the two broadly defined regions each with characteristics distinctly its own. The former spilled over into Old Mexico, and the latter extended into the adjoining Rocky Mountains and up into Canada. The Southwest was marked with blistering heat and waterless deserts, cactus and drab Apaches; the Northern Plains was a vast expanse of grassy buffalo range, timbered hills, beautifully garbed Sioux and Blackfeet, and freezing winter blizzards. The white men who roamed the wilderness areas of both regions rook on different characteristics. The trappers and the cowboys were different, and even the Army had to learn a whole new catechism of service, combat and survival when they were moved from one region to the other. Years of association brought some men to love one area and hate the other. The great herds of buffalo migrated from one area to the other to avoid the intense heat or bitter cold. It might almost be said that only white men and rattlesnakes adapted themselves with equal facility to making a home of both regions.

During the first couple of years after Remington went West in 1880 as a nineteen-year-old adventure seeker, he roamed the overland and cattle trails through the back country from the Canadian to the Mexican borders. In spite of his comfortable and even aristocratic family background, and his sophisticated days at Yale, something very deeply rooted in his nature made him intensely devoted to the roughest aspects of frontier life. In both the north and the south he made his friends in the cattle country saloons and the other rendezvous of the white man and Indians who had given character to the earlier days, and he acquired their strong distaste for the passing of the Old West.

The story of the Old West is also the story of one of the longest and most extraordinary conquests by the white race of another race for the possession of a national homeland. Historically it is very important. The last thirty years of the nineteenth century were the most intensive of the transition period, in both the north and south. Remington came early enough to become intimately familiar with the lingering vestiges of what had gone before, and he was an eye witness to the grand finale. In his pictures he covered it all—for he was fundamentally an artist. Although the articles and stories he wrote are frequently difficult and sometimes impossible to pin-point as to date or chronology, they all have the one basic theme of the passing of the Old West, and they easily fall into the categories of the Southwest and the Northern Plains, It is for these reasons that they have been grouped in two parts—and arranged in as nearly a chronological order as possible.

The first pictures that Remington published were of the Southwest and there seem to have been few years between the beginning of the 1880’s and the end of the century that Remington did not spend some time in that region. What he wrote can be taken as soundly documentary, and it represents what is probably as clear-cut an impression of the people and the period as any historical treatise can convey. Here is drama, the struggle and bitterness of two races amid heat and thirst and sweat—the one striving in their own way to retain an ancestral homeland, and the other waging a war of subjugation to make a national homeland for his own people. Here is the Southwest, in transition from the old to the new. Here is Frederic Remington’s own account of that struggle.

—H. McC.

CAVALRY ON THE SOUTHERN PLAINS

I—Soldiering In The Southwest

(An unpublished manuscript)

In any historic recounting of the Apache war, the soldiers must come in for their share, although there are some folks who say, “these soger-chaps is hired to do thirteen dollars’ worth of fighting per month and I’ll be blanked if I think they earn their money.” No man earns his wages half so hard as the soldier doing campaign work on the Southwestern frontier. He may not do thirteen dollars’ worth of fighting every month, but he does marching which under special contract he might agree to furnish for $5,000 per turn of the moon. Altogether, the duties imposed on the troops of General Miles [foremost of the U.S. Army leaders in the Indian wars in the West] are as onerous and unprofitable as any within the category of military operations. They cannot end their campaign by a battle, trusting to their god of war for the result. They are fighting a mountain people in their own mountains, who have, no base, no objective point of attack, nor any false idea of military glory or even comity to defend.

Today [1889] the Indian is mounted fresh, and tomorrow night he is remounted on stolen stock; he can subsist himself in competition with the coyote on the desert; he has an abundance of ammunition; and at his back is a mountain stronghold known only to himself and all but impassable to his enemies, from which he sallies out, dealing a demoralizing guerrilla warfare on the defenseless white inhabitants of the valleys. Before the news reaches the soldiers, he has stretched miles of desolate desert behind the flying feet of his pony. Still, realizing the obstinate pursuit, he pricks on his flagging horse until the heaving flanks and faltering gait show inability to keep the terrible pace, when, with an ungrateful stab of the knife, he takes to his heels and leaves the poor panting, bleeding pony to die on the trail. Thus is he rewarded for his gallant effort by his fiendish rider and thus is the Apache at war with even the beasts of the fields.

The tired cavalry horse plods along in the hopeless pursuit, spurred and goaded to the utmost limit of his endurance. Poor beast, while in his humble way he bears the brunt, the marching, and the suffering of all cavalry war, no report mentions him, no pension awaits, no one knows, no one cares.

Much of this is also true of the trooper rider, whose identity never gets beyond his orderly-sergeant. His heroism is called duty, and it probably is. On the long march it is his task to nerve his tired muscles and keep in place. It is his duty to eat the scanty fare and perchance to carry off a vicious bullet wound or be buried in the sands of Mexico. It is his duty to do many things that stretch that word to its good Old English tension. And, after all, who are these lowly wearers of the blue? Oh, very matter-of-fact persons, with no sense of the heroic, with a lack of moral fiber perhaps, rude of manners and soldiers because of circumstances once and force of habit now. For instance, the tall young fellow with the smooth face on the roan horse is Jack Hazard―lived somewhere in Connecticut, got broke in New York City, and enlisted. That bronzed and grizzled old pirate with the black mustache and goatee, good type of the “army in Flanders,” is serving his fifth enlistment and couldn’t get a living out of the Army, The red-faced chap with the yellow mustache has served King William as a hussar; and Mike O’Malley there is a worthy descendant of the old stock—his kind are in every army, in every clime. These are the “crows”; Natchez’s men are the “kites”; the dark canyons and lofty peaks of the Sierra Madres, the Santa Ritas, the Whetstones, the Dragoons, and the Santa Catairinas are the battlegrounds. Official reports bear no romance in their lines, and the half that these rocks have witnessed will never be known.

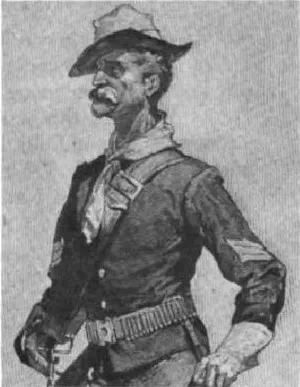

As this is a soldier’s scrape, we naturally look him over more closely. Indeed, he is a strange soldier. His brass sans glitter, his accouterments unblacked, he is covered with dust and much that was dust once but is a firmer deposit now, all plainly saying “the regulations be hanged!” His boots are red, one spur is gone, his pants are reinforced with buckskin and worn to a state of impropriety; his shirt is open at the neck, his blue coat is a dull mauve color, his hat, a battered ruin, and his skin, burned carmine or swarthily tanned, while a good stubble of beard completes all that is lacking to metamorphose our soldier into a veritable buccaneer.

Once I met a young officer some two months out from Governors Island, full of the books and much more knowledge begotten of the confidence of youth, who informed me after I had expatiated on the delightfully vagabond types these soldiers presented to an artist “that all soldiers look alike, you see one, you see all.” While this is the theory and passes for true in the Atlantic garrisons, in General Miles’s department the practice is at a wondrous variance, Pipe-clay elements are dropped for want of time to attend to them. Some of the men have not been in garrison for a year, and at times their ingenuity is taxed to appear decent.

The infantryman in his brown canvas clothes has more the look of a navvy than the smart military character, and frequently a toe has worked through a shoe until it much resembles a mud-turtle, imparting to its wearer the social air of a tramp. The villainous knives issued to the “doughboys” complete a sinister aspect, for they would look a part and parcel of the Genghis Khan; still, they have their use in the domestic affairs of the soldier while serving in place of the discarded bayonet. Another exponent of the foot soldier, the knapsack, is also gone, while the ammunition belt has relegated the cartridge box to the arsenals. A big tin cup flaps from its fastenings on the haversack, and the “set” of the pantaloons, tucked and wrinkled in the service boots, is far from fashionable.

The scouts, packers, and teamsters add artistic qualities in their strongly molded faces and businesslike get-up that the most casual onlooker could not but perceive. It readily occurs to one that he would not care to meet them in the dark, but the proof of the pudding shows them to be exceptionally honest, pleasant men in their way—only their lives are earnest and altogether discouraging to the dandy tendencies. Should one be disposed to ferret out strange characters, here is his “feast of reason”; for these men have not followed their dangerous callings and made personal histories rivaling the yellow-novel heroes without a mind peculiar, a character sturdy, and a training far from matter of fact. They will greet you roughly, with a thorough lack of conventionality, in the dialect of the frontier; and if you sabe [understand] them they are no end of friends; and spreading your blanket beside them, you may feel fortunate if you never sleep in worse company in your Western rambles.

The Indian scouts employed as trailers will certainly attract attention. They are San Carlos and Tonto Apaches, wild and savage as any race of men who ever lived; lithe and sinewy, with sharp eyes and quick, bright ways; quite different from their stolid brethren of the north. They wear the usual garments made of cotton cloth, with a colored fabric wound round their heads, allowing their manes to flow about their face and shoulders. In walking, they move off smartly, working from the hips, running with ease uphill, and as the saying goes, “they rest while coming down.” The tales of their endurance in traveling are almost incredible. That they are cruel, one does not have to look a second time to guess; he does not have to see them torture a rabbit as a pastime, for the subdued ferocity of the tiger is in their eyes and gleams out savagely at times, beyond their will to suppress. A villainous-looking Mexican named José Marie is their interpreter. He has spent his life among them, having been captured when a child and since adopted into the tribe, where he doubtless is considered a very fair Apache for a Yaqui mongrel. He shouts his interpretations at them after the manner of a Mississippi River mate in the boating days of old. Truly as heterogeneous a combination of soldier elements as the reign of war can bring together, and certainly interesting to observe, is this phase of life so important in American history, which is fast passing away.

In following the fortunes of Miles’s troopers, the first impression is the beautiful simplicity of camp life. Robin Hood is outdone, for he had the forest trees above his head. Where the saddle is taken from the horse’s back and thrown upon the ground is camp, without more ado or advancing. The aspect of a tented field is entirely missing.

In the early morning, as the night grows pale with coming light, the horse herd comes up from its night on the range at a good round trot, unconsciously keeping in the form of a column, showing the impress of a military life on the equine nature. The Apaches’ chosen ground not being made for the echoes of a trumpet, no bugles blare; but the simple calls of the sergeant summon the men. “Catch your horses,” comes the command amid the hurrying of many feet as the herd rounds up. The horses are caught and picketed, the breakfast eaten, the saddlebags rationed, because this is a warm trail and before the command “Halt” is given, sleep will be more necessary than eating.

“Come boys, get a motion on, that air mu-el will just naturally die of old age if you don’t rustle,” shouts the boss packer to his assistants. The ropes fly in the mystic circles of the “diamond hitch” as the big packs are bound on the apperajos [saddlebags]. The mule strains, lays his ears back, ...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- INTRODUCTION

- PART ONE-IN THE OLD SOUTHWEST

- PART TWO-ON THE NORTHERN PLAINS

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Frederic Remington's Own West by Frederic Remington in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.