- 219 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Greek City-States

About this book

A renowned scholarly text on ancient Greek history authored by the Welsh University scholar and lecturer Kathleen Freeman, this book deals with 9 of the hundreds of great and small Greek city-states (polis in Greek word, from which the word "politics" is derived) which occupied sites from the western Mediterranean to the coast of the Levant, from the Black Sea to North Africa at a time when Greek civilization was at its zenith.

As Freeman explains in her Preface, "[i]f the Greek world is really to be understood we must know not only about Athens and Sparta, but about the islands of the Aegean Sea, the Greek cities of Sicily and Italy and Asia Minor, and the other cities of mainland Greece," and she thus casts this fascinating book in the form of a series of individual city-studies.

A must-read for every Ancient Greek historian, scholar and enthusiast.

As Freeman explains in her Preface, "[i]f the Greek world is really to be understood we must know not only about Athens and Sparta, but about the islands of the Aegean Sea, the Greek cities of Sicily and Italy and Asia Minor, and the other cities of mainland Greece," and she thus casts this fascinating book in the form of a series of individual city-studies.

A must-read for every Ancient Greek historian, scholar and enthusiast.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1. THE RISE AND FALL OF THE GREEK CITY-STATE

THE OUTLINE of the history of ancient Greece reads like a tragedy in three acts.

The first act is full of promise. A series of migrations of Hellenic peoples populates the peninsula of Greece, overwhelming the inhabitants by force or by peaceful pressure; the last and most violent of these migrations, the Dorian invasion, drives earlier Greek invaders further south and even overseas. A period of assimilation follows; and out of chaos there emerge the principal city-states of the ancient Greece we know: the new Athens, centre of government for Attica; Sparta, Corinth, Megara, Thebes and the rest; the Aegean island-states and the great commercial city-states on the coast of Asia Minor. These communities flourish; overseas trade expands; new sources of wealth are eagerly sought; and a new colonization movement, lasting over two centuries, begins. The shores of the Black Sea, the coasts of Sicily and southern Italy, are occupied; and trading-posts are planted further west and on the coast of North Africa. The Mediterranean, the Aegean and the Black Sea have become largely Hellenic, though the Phoenicians and their colony Carthage remain to challenge Greek trade supremacy.

This Hellenic world, far from being a solid bloc like a nation, consisted, like the solid-seeming substances analysed by Democritus into atoms and void, of countless units separated in space and varying in size from large communities like Athens and Syracuse to mere trading-posts like Sestos and Abydos. Nearly all these communities were completely independent: each was free to ally itself or go to war with a neighbouring city-state; each judged its own policy at every step by the standard of immediate self-interest. The colonies, even, in spite of a sentimental regard for the mother-city, were not bound to pay any heed to her wishes in peace or in war; and racial ties within the Hellenic people, such as those forming the Dorian and Ionian groups, did not prevent these groups from being split by the wedge of self-interest, as the Peloponnesian War was to show.

It is a curious fact that in spite of the Delphic injunction “Nothing too much,” and the reputation of the Hellenes for devotion to Reason and the Mean, they themselves tended to extremes in the experiment of living. In fifth-century Athens an extreme form of equalitarianism among free adult males still arouses astonishment: all officials, except the War Board of ten generals, to be chosen by lot from those eligible. In Sparta there was an extreme cult of physical fitness and militarism which can still provide a bad example. Acragas went to extremes in religion, as the magnificent ruins on her crowded hilltop still demonstrate. In the same way the Hellenic race displays to the historian the most intense passion for separatism that the world has ever seen. The hundreds of city-states had nothing in common except their descent from a common stock and their basic language, both of which meant a small common heritage of beliefs and ideas. Yet they contributed in less than a millennium more to the human treasury of civilization than all the rest of the world put together throughout all its known history.

Why did their civilization perish? It is generally believed that it perished because they were unable to sink their differences and combine. The second act of the tragedy, while showing superb intellectual achievement, also shows constant wars between city-states which weakened both victor and vanquished. There was not only the great struggle lasting for twenty-seven years between Athens at the head of her empire and Sparta at the head of her confederacy: there were many smaller struggles from time to time, in which neighbour destroyed neighbour and weakened Hellas in the face of the barbarian. For instance, the flourishing city-state of Sybaris on the south coast of Italy was wiped out in the late sixth century B.C. by her neighbour Croton, only sixty miles away, so that the very site remained uninhabited for over half a century after: this though the Greeks formed a mere fringe on the coast, with a hinterland of natives whose attitude was often hostile and always uncertain. On the island of Sicily the Greek settlers were never in full control: the interior was occupied by native Sicels and Sicans, and the western tip by the bitterly hostile Carthaginians, whose base lay across the Mediterranean at a distance of only one hundred and fifty miles. Yet the Greek city-states were never able to achieve unity. Syracuse, for instance, which by its size and strength was obviously destined for the role of leader, turned on its own colony, the little town of Camarina fifty miles away on the south coast, and destroyed it in 552 B.C.; recolonized it in 495 B.C., and destroyed it again ten years later, at a time when the Hellenic world was facing its great struggle against the barbarian, Persia in the east, Carthage in the west. These are only two examples among many.

But, it is often believed, the Greeks of the mainland at any rate, though apt to quarrel in times of peace, were able to unite in times of external danger. This is quite untrue: it is an opinion based on the famous stand of the defenders of Greece against the Persian invasions of 490 and 480 B.C. Few realize even now how very far the city-states were from achieving unity. In the former of these invasions the Persian army came by sea across the Aegean to Attica, and landed at Marathon; they had no fear about what was happening in their rear, because the whole of northern Greece, Thessaly, Thrace and Macedonia had already given tokens of submission to the Persian envoys, as also had the island of Aegina, actually within sight of the Piraeus. The victory of Marathon was almost entirely Athenian: the Spartans, having no great love for the Athenians, came too late; they themselves, only sixteen years earlier, had sent an army into Attica in an attempt to interfere in Athenian internal affairs. In the second great invasion, that under Xerxes in 480 B.C., the Spartans did send an army further north; but when this was wiped out at Thermopylae they were very ready to abandon Athens to her fate, and Athens was actually evacuated and occupied by the enemy. The sea victory of Salamis reversed this; but Athenians owed their salvation to their own exertions, not to any concern on the part of the more southerly city-states for their preservation. In later days the Greeks themselves liked to look back on this period as a time of Hellenic unity; but it was nothing of the kind. It was a brief spell when certain of the city-states consented unwillingly to fight side by side in the pressing cause of self-preservation.

The moment the immediate peril was relaxed they returned to the expression of their mutual enmity: the Peloponnesian cities to the building up of a confederacy hostile to Athens, the Athenians to their policy of the domination of the Aegean. All the city-states, in whatever they did, were governed by immediate self-interest: those that joined Sparta—Corinth, for instance—did so because they hoped that Sparta would use her military power to check Athenian expansion, which menaced their prosperity; those that joined Athens, in the hope of enjoying profitable trade relations and the protection of her fleet. When they found that Athens intended to use them in order to build up her own power, the larger states, such as Samos, attempted to break free, and were brought back into the Athenian power-orbit by force. Others, like Chios and Lesbos, revolted during the terrible Peloponnesian War, which broke out in 431 B.C. and lasting twenty-seven years drained both sides of their strength; they became, in the following century, an easy prey for the military adventurer, King Philip of Macedon, a man who, though his race and language were Greek, was nevertheless completely un-Hellenic in outlook, and who, with his son Alexander, did in fact destroy for ever the civilization of the city-states.

It was during this second act of the tragedy that all the best of what Greece has given us, with the exception of the epic, was produced. This period saw the rise of science and philosophy in Miletus, Sicily and southern Italy, and its perfection in Plato and Aristotle; the lyric poetry of Pindar; the Athenian drama; the prose historical work of Herodotus and Thucydides; the work of Solon and other legislators; Athenian oratory; the birth of scientific medicine under Alcmaeon of Croton, Empedocles of Acragas, and Hippocrates of Cos; mathematics, astronomy, biology, the art of education, painting, music, sculpture, architecture and much more. Truly, as Heraclitus said, “War is the father of all and the king of all”. The constant struggle for power and wealth between the city-states themselves was mirrored in their internal strife, in which oligarch and democrat plotted and murdered (judicially or by straightforward massacre), and where the opposition party was usually willing to sell its state to the enemy in return for political power. Philip of Macedon brought the use of the bribe and the internal band of supporters (or fifth column, as we call them) to a fine art, preferring them to the sword; but long before his day they were a familiar weapon everywhere. When the struggle between Athens and Sparta was at its height plot succeeded plot in Athens to dislodge the democratic government: exiles were scheming outside; the anti-democratic, pro-Spartan party within. When the Spartans were victorious they were able at once to put the government into the hands of a committee of thirty Athenian oligarchs, who were not only the willing tools of the conquerors but who also indulged during the eight months of their power their passion for wealth and their political and private hatreds. Athens was surely paying for her many political and military crimes: her subjection of the Greek islands, her cruelty to Melos, her attempt to subdue Syracuse. And while Greek destroyed Greek, the Persian power intrigued in the east, and the Carthaginians attacked the Sicilian Greeks in the west, capturing the wealthy city of Acragas after an eight months’ siege and destroying her neighbours on that coast—Gela, and the unfortunate Camarina, already twice destroyed by fellow Greeks. This was in 406-405 B.C. The surrender of Athens to Sparta was in April 404.

The third act of the tragedy, the break-up of the city-state system, bringing with it the end of the distinctive thought and work of ancient Hellas, begins from then onward. Throughout the first half of the fourth century the menace grows. Yet the mainland Greeks do not unite. Fresh combinations are formed: Thebes invades the Peloponnese and attacks Sparta; Athens goes to Sparta’s aid for a time, but the uneasy alliance cannot last, since neither side has good will towards the other. Philip of Macedon comes to his throne in 359 B.C. and at once begins his activities, aimed at the domination of the Hellenic world. His Athenian opponent, Demosthenes, completely clear-sighted and completely courageous, has to see his efforts to rouse his fellow-countrymen to a sense of the danger thwarted by time-serving rivals like Aeschines and sentimental doctrinaires like Isocrates, the former hoping for political power, the latter preaching the out-of-date cause of union against Persia. There was at this time a spate of rhetoric about “concord” and “unity”, but to all such talk the common citizen opposed a scepticism that baffled even the plainest speaking, and a lethargy that was impervious to all warnings. To those of us who suffered from a similar sense of impending disaster during the years between the First and Second World Wars, there is no more poignant reading in all history than the speeches of Demosthenes, in which that great man strove with all the force of piercing insight and consummate oratory to awaken his fellow-citizens to the danger. Again and again he warned, and his warnings came true; but still the response was “too little and too late”. And yet, only a quarter of a century ago, an historian of Greece could write of Demosthenes: “To the last, indeed, he failed to see things in proper perspective”, and of Philip as the “lover and promoter of Hellenic culture”. Truly, as Mr. Churchill once said in another connection, this “falls into that long, dismal catalogue of the fruitlessness of experience and the confirmed unteachability of mankind”.

Sixteen calamitous years saw the crushing defeat of Athens at Chaeronea; the death of Philip two years later, in 336 B.C., and the brief revival of hope; the campaigns of Alexander, in which the opposition of the Greek city-states was hardly sufficient even to delay the main enterprise, the subjugation of the east; the death of Alexander in 322, and the second brief resurgence, easily quelled; the flight of Demosthenes and his suicide to avoid capture. With these events the political life of the independent city-state ends for ever, as Greek philosophy dies with Aristotle in exile at Chalcis. Macedon was not Greece: the rule of the Macedonian generals in Asia Minor and in Egypt begins a new uneasy period of history, when the Hellenic world awaits absorption into the unifying realm of Rome.

What is the moral of this tragic story? Why did the vivid and distinctive Hellenic civilization not survive, or survive only as an influence in those of other peoples? The customary explanation is “lack of unity”; but this is to mistake the symptom for the cause. Perhaps a closer view of some of the most representative city-states other than Athens and Sparta will suggest an answer less superficial and more instructive to the modern world.

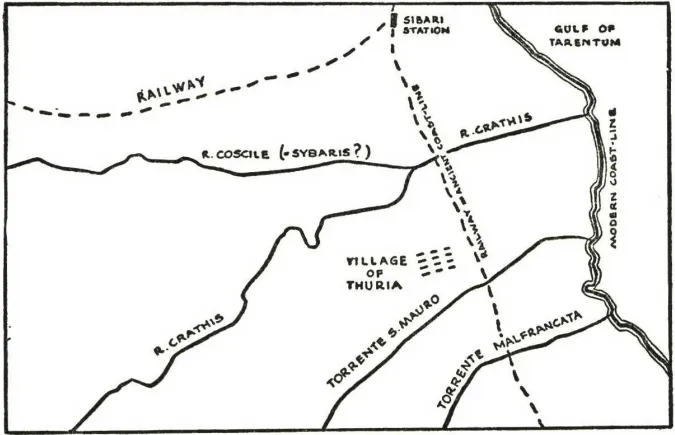

2. THOURIOI

ON THE coast of southern Italy, just before the coastline changes its direction from south-west to south-east, there was in ancient times a place where the high mountain range stood back a little, and in front of these mountains a series of semi-circular terraces formed a kind of giant’s amphitheatre looking out to sea on the Gulf of Tarentum. At this spot two rivers flowed close together into the sea; their alluvial deposit had built up a small fertile plain, and the route taken by the larger of them down from the mountains pointed to a short cut to the sea on the other side, the Etruscan Sea. Here, in the latter half of the eighth century B.C., a band of settlers from Achaea in the north of the Peloponnese built a town between the two rivers, which they named, as colonists tend to do, after a river and a spring in their homeland: the larger river they called Crathis, “the Mixer”, and the smaller Sybaris, “the Gusher”. The newly-built town took its name from the Sybaris. Both these rivers are there today: the Crathis is still called the Crati, and the Sybaris, which now flows into the Crati, is called Coscile.

On the brief but notorious history of Sybaris a great deal of nonsense was written in ancient times. Sybaris was extremely prosperous, and it attracted the envy and hatred of its poorer neighbours. Strabo the geographer, grossly exaggerating, says that in its heyday it governed four neighbouring tribes, twenty-five cities and could put 300,000 men in the field. The stories of Sybarite luxury vied with one another in prodigiousness; and when disaster finally befell the city in 510 B.C., some two centuries after its foundation, this seemed to historians one more example of the work of Nemesis. A quarrel broke out between Sybaris and the neighbouring Greek city-state of Croton, where the philosopher Pythagoras was living and teaching. The people of Croton, though at first afraid of their powerful neighbour, took the advice of Pythagoras and chose war. The result was that Sybaris was captured, the inhabitants either slain or driven away to the hills, and—so the story goes—the river Crathis was diverted by the Crotoniates over the site of the town, so that not a trace remained. Some modern writers maintain that this would have been beyond the powers of the Crotoniates as an engineering feat; but Herodotus, who later lived at Thourioi, believed it: he wrote of the dry bed of the old river, and of a temple of Athene that had later been built there.

For a time the site remained completely deserted. The scattered survivors lived at other Greek cities on the west Italian coast, and from time to time attempted to return to the old site. Once, nearly sixty years after the disaster, the site was occupied by some Greeks from Thessaly. But all these attempts were foiled by their jealous neighbours, who refused to allow the town to rise again; and the settlers were never strong enough to resist them. At last the persistence of the exiled Sybarites—by now the children or grandchildren of those who had survived the disaster—was rewarded. The possibilities of the place attracted the eye of Pericles, then at the height of his power as virtual ruler of Athens. He saw how useful it would be to have an Athenian outpost there on the coastal route to Sicily, at a spot where in bad weather the passage of overcrowded boats through the strait could be avoided by sending the men across land and the ships round to meet them. He therefore took pity on the Sybarite remnant (it is said that these had sent delegates to Sparta and to Athens, but the Spartans paid no attention), and decided to take the initiative in refounding Sybaris.

And so we come to the founding of Thourioi, as the new city-state came to be called. All was done with due form and ceremony. This colony was to be no haphazard affair like the settlements of the old adventurers; it was to be as well begun as modern Periclean science and political skill could make it. It was not to be a purely Athenian venture: a proclamation was sent round the cities of the Peloponnese, offering a place to anyone who wished to join. Many accepted. Among these was a Spartan named Cleandridas, banished from Sparta on suspicion of having accepted a bride from Pericles not to invade Attica the precious year. This man’s son was to prove a bane to Athens thirty years later: he was Gylippus, the man mainly responsible for the disaster which overtook the Athenian army and navy blockading Syracuse.

Meanwhile the Delphic oracle was consulted, according to custom. The Pythian priestess rose to the occasion with a special riddle: “You must found your city where you shall drink water by measure, and eat barley-cake without measure.” Other professional seers were called in: Athens had no lack of these. Altogether ten seers made the voyage to Thourioi, perhaps one for each of the ten ships that sailed; they took such a prominent part in the expedition that one or other of them was often said to have been its leader, or even to have founded Thourioi. They were certainly prolific in prophecies about the future of the colony; and they evidently founded a school of seers there. Twenty years later they were being held up to ridicule on the Athenian comic stage as a type of lazy humbug.

The expedition sailed. The number of colonists sent by Pericles is not recorded; but besides the Athenians many others to whom the proclamation appealed or who had reasons for wanting to leave home joined en route. When they reached the coast of Italy and had sailed round to the mouths of the rivers Crathis and Sybaris, they were no doubt met by the original Sybarites and others wishing to share in the new venture. The first thing to look for was the spot indicated by the Delphic oracle; and they soon found something that would do. They came to a spring from which the water flowed through a bronze pipe, which the natives called medimnos. The medimnos in Athens was a dry measure; they therefore decided that this answered the riddle: “The place where you shall drink water by measure, and eat barley-cake without measure.” This spring was called Thouria, “the Rusher”, and was shortly afterwards to give its name to the new city. But at first the settlement was given the name of the old city Sybaris: the first coins struck there bore the head of Athena and the inscription SYBARI.

Ancient writers are agreed that the new city was not laid out on exactly the same spot as old Sybaris. Perhaps the latter was actually annihilated and obliterated by the diversion of the river; at any rate, the site of Sybaris has not yet been determined. The site of Thourioi, however, is known; and Italian archaeologists claim to have discovered even the spring “the Rusher” which led to the choice of site. The he of the land has altered considerably since those days; the two rivers have now joined, and flow together into the sea, and their alluvial deposit has altered the coastline, adding con...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- MAPS AND PLANS

- ABOUT THE AUTHOR

- PREFACE

- 1. THE RISE AND FALL OF THE GREEK CITY-STATE

- 2. THOURIOI

- 3. ACRAGAS

- 4. CORINTH

- 5. MILETUS

- 6. CYRENE

- 7. SERIPHOS

- 8. ABDERA

- 9. MASSALIA

- 10. BYZANTIUM

- 11. CONCLUSION

- BIBLIOGRAPHY

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Greek City-States by Kathleen Freeman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Ancient History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.