![]()

THIRTEEN—Koch Attacks Tuberculosis

IT WAS now August of 1881, and the Imperial Health Office sent Robert Koch as one of the German delegates to the International Medical Congress in London.

Here Koch met the most famous medical men of his day. Among them were Louis Pasteur, the great French microbe hunter, and the two famous English surgeons, Lord Joseph Lister and Sir James Paget. Rudolf Virchow was also there, but Koch took pains to keep away from him.

Although Lister, Pasteur, and Virchow—the leading lights of their respective countries—dominated the Congress, Robert Koch now became known in England. In Lister’s own laboratory at King’s College, Koch demonstrated his new technique for growing pure colonies of microbes.

Despite the fact that Koch had spoken out against some of Pasteur’s work a few years earlier, Pasteur generously rushed up to Koch and exclaimed: “This is certainly great progress, Monsieur!” Unfortunately, these two great scientists were to remain opponents the rest of their lives.

Years later, a curious question arose about this same London Medical Congress. Did Robert Koch—at this early date—actually show anyone in London that he had grown a pure culture of tuberculosis?

One report says that he did. And to no less a person than Lord Lister himself! Other reports say that Koch could not have made any such discovery for he had only made his first inoculations of tubercular material on his return from London.

The truth is that probably Koch had talked of the dreaded disease to Lord Lister—and to anyone else who would listen. It was a great deal on his mind. Since his Rakwitz and Wollstein days, he had come to hate this killer of men, women, and children.

When Robert Koch returned to Berlin, he knew he had now perfected the basic tools with which to fight a most vicious disease—tuberculosis.

For hundreds of years, tuberculosis had been the most dreaded of human diseases. During the nineteenth century, over thirty million persons had died of it. In Europe and America alone, the disease regularly claimed the lives of three people out of every seven.

Called “the White Plague,” tuberculosis had always been terribly widespread. Over the whole globe, no one was safe from it. Moreover, tuberculosis was seldom detected until it had reached an advanced stage—too late for anyone to do anything about it. There was nothing, in fact, for a tubercular patient to do except prepare for a long and agonizing illness. If by some lucky chance he recovered, no one would believe that he had had tuberculosis in the first place.

As early as the ancient Greeks, tuberculosis had been a common killer. The Greek physicians called the disease phthisis, which means “wasting away.” Later, the marauder was called “consumption” from the Latin word consumere—to consume, or eat away. Both these names arose from the disease’s chief symptom; namely, the gradual wasting away of the body. Ancient physicians tried to fight the disease by building up the body through diet, change of climate, and proper exercise and rest. Although this means of combating tuberculosis was quite sensible, it was usually ineffective, for diagnosis of the disease often came so late that the treatment was of no use.

Consumption continued to be as baffling as it was deadly in the centuries that followed. It was not until Koch’s own century that medical science began to penetrate the mystery of the disease.

In 1839, a Swiss physician, Dr. J. L. Schoenbein, pointed out that little growths called tubercles—knobs or tiny lumps—were often found on the bodies of persons who had died of consumption. Schoenbein then suggested that the disease should be called tuberculosis.

But neither Schoenbein nor other medical men of his time could seem to settle one important question about tuberculosis. Was this killer a contagious disease—one that was introduced into the body from outside? Or was it a constitutional, or inherited, disease—one that arose of itself in the body, or that was passed on from parents to children? Many medical men, including Virchow, favored the latter view.

“The disease is doubtless inherited,” this school stated gloomily. “If your father had tuberculosis, the chances are good that you will probably get it.”

Actually, the one thing that was known about the disease was that it had to be caused by some kind of microbe, for medical researchers had succeeded in transmitting it from infected human beings to healthy animals. A French physician, Jean-Antoine Villimin, had already demonstrated this. So, in fact, had Koch’s friend, Julius Cohnheim. He had put a bit of sick tissue from a tubercular patient into the eye of a rabbit and the animal had died of consumption.

Cohnheim’s work made many scientists believe—rightly—that the cause of tuberculosis was a living “something.” Cohnheim himself predicted that soon someone would find “tubercle particles,” as he called them. Encouraged by this, other scientists set out at once to work on the problem of finding these “living somethings.” Between the years 1877 and 1881, a whole series of men claimed that they had found the cause of tuberculosis. While it is probable that many of them really did see the tubercle bacillus, they were unable to stain it with dyes or otherwise bring forward enough proof of their discoveries.

Meanwhile, the treatment of those who had the disease had not advanced much either. The only new scheme had been to send tubercular patients to places called sanitariums—retreats usually located high in the mountains where they were supposed to get better by sitting outside wrapped in blankets, and breathing in the clear mountain air. However, since the question of whether consumption was catching or not had not been settled, the sanitariums dared not suggest any sanitary regulations concerning tuberculosis. Thus there was no fumigation (disinfecting by gas or smoke), no sterilization, no laws about spitting, and no really advanced means of diagnosing the dreaded disease.

In the summer of 1881, Robert Koch set out on the trail of this “living something”—the tubercle bacillus. Those who knew him well were aware that no subject interested him as much as this dreaded disease.

“Cholera, bubonic plague, and other diseases,” Koch once said, “carry off their hundreds, even thousands. But tuberculosis claims its victims in all civilized countries in the tens of thousands.”

His practice in East Prussia had taught Koch that few families escaped tuberculosis—some member somewhere was always being struck down by it. In fact, Koch was so impressed with the deadliness of tuberculosis that throughout the rest of his life—even to the very end—he let no chance escape to further investigate it.

Moreover, Koch was always very practical in his work. He made it a point always to know where he was going—or at least try to know.

Thus, in beginning his research on tuberculosis, Koch had already worked out in his mind a set of rules as a guide to further experiments with microbes. These four rules, which he later published, have become known as Koch’s Postulates. They are considered fundamental in bacteriology today:

1. In order to prove that a certain microbe is the cause of a certain disease, that same microbe must be found present in all cases of the disease.

2. This microbe must then be completely separated from the diseased body and grown outside that body in a pure culture.

3. This pure culture must be capable of giving the disease to healthy animals by inoculating them with it.

4. The same microbe should then be obtained from the animals so inoculated, and then grown again in a pure culture outside the body.

If, reasoned Koch, these four conditions could be fulfilled in the case of the tuberculosis microbe, the chain of evidence would be complete. He would then have isolated and grown pure the cause of tuberculosis—the tubercle bacillus.

From the beginning, Koch had to advance step-by-step, inventing new techniques and culture-growing media as he went along.

True, Koch had always been a hard worker and accustomed to many failures. But now he never worked harder—and never did he fail as often. Again, too, he was searching alone, for his two brilliant assistants were tracking down microbes of their own; Gaffky was later to isolate the typhoid bacillus and Loeffler, eventually, that of diphtheria.

Koch had studied Cohnheim’s experiments closely; he decided to repeat the experiment of giving tuberculosis to healthy animals. First, he obtained some diseased tissue from the body of a recently dead laborer. A large, powerful man of thirty-five, this victim had entered Berlin’s Charity Hospital only days before. As the days went by, the man’s cough grew worse; he spat up blood and complained of terrible pains in his chest. Soon his once-superb body had wasted away until he was only a bag of bones. Then the man lay dead, his tissues shot through with the yellowish speckles of tuberculosis.

Koch peered into every part of the unfortunate man’s body with his microscope. Day after day passed and he could see nothing more than the dead tissue itself. Nevertheless, he kept inoculating his laboratory animals with the diseased stuff, wondering how long it would take the deadly material to cause their deaths.

While he waited, Koch hurried every morning after breakfast to the Charity Hospital to obtain additional diseased material for his investigations. He inoculated more and more guinea pigs and rabbits with tuberculosis. When they eventually wasted away and died, Koch used their diseased tissues for study. Still, he could not seem to manage to see the killer-bacillus through his microscope.

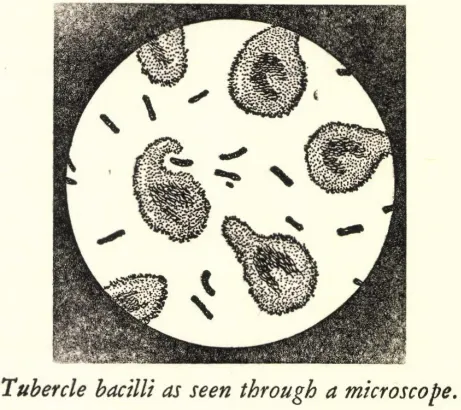

Two things were now clear to Koch. Unlike the anthrax bacillus, the tubercle bacillus was a very small microbe indeed. Thus, the job of isolating it—even seeing it—would be that much harder. Also, the microbes of tuberculosis were slow growers compared with the fast-multiplying ones of anthrax. Therefore, his attempts to grow them would take far longer.

Still, Koch was sure that the bacilli must be in the tubercles, or tiny lumps, that he found in the tissues of those who had died of tuberculosis. Yet even when he ground them up and looked at them with the best microscopes available in Berlin, he could not see the bacilli. He then tried various methods of dyeing his specimens.

As the days went by, Koch’s hands turned nearly every color of the rainbow as he experimented with different dyes. Then they would turn jet black as he dipped them constantly into bichloride of mercury to kill any stray microbes that could have ruined his experiments.

Finally, he found that the dye called methylene blue seemed to be best for his purposes. Now he kept his glass slides for long hours in this blue stain, hoping eventually to see the tubercle bacillus itself.

One day he removed one of his glass slips from this solution and slid it under his microscope. From the tiny chunks of cheesy tubercular matter, a deadly picture emerged for Koch to see. There they were at last—slim, little blue-colored rods—the bacilli of tuberculosis! Far smaller and more curved than those of anthrax, Koch estimated they could not be longer than one fifteen-thousandth of an inch.

The material Koch was examining was a bit of diseased tissue from the dead laborer. He now examined other specimens—from this man—that had also b...