This is a test

- 153 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

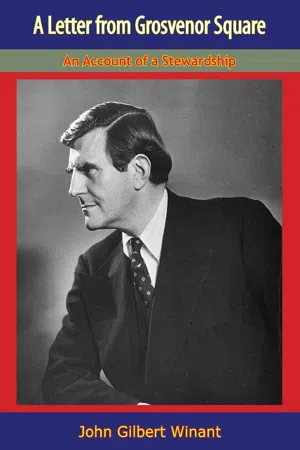

In England's darkest hours, John Winant, U.S. Ambassador, became to the British a symbol of American fellowship and support. They looked up from the still-smoking rubble of their homes and saw him standing strong with the King or with Winston Churchill.As Ambassador, his chief concern was not only immediate agreement and understanding between the two countries, but also long-term good relations. In the account of his stewardship, he not only shows American generosity, but stresses the less known—but not less important—contributions which the British made to us through reverse Lend-Lease.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access A Letter from Grosvenor Square by John Gilbert Winant in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Lend-Lease and Foreign Exchange

NOW I want to speak about the making of modern war and look at the relative position of Great Britain to Germany and Italy in manpower, armament, food, trade, and foreign purchasing power at the outbreak of the war.

In order to get a correct measure of the time, it is necessary to go back to the pre-war period rather than be wise after the event. It helps, also, to tie together many apparently unrelated and isolated facts in trying to evaluate correctly the importance of Lend-Lease. The Prime Minister described it as the “most unsordid act in the whole of recorded history.” It is probably true that no act of a neutral power ever contributed more to the defeat of an aggressor nation. The Lend-Lease program was before Congress when I left the United States. It had been recommended by the President in his Annual Message to Congress. It was approved by large majorities in both Houses and became law on March 11, 1941.

Lend-Lease was an invention of the President that opened the way for giving immediate and effective aid to those defending democracy, and it was designed to avoid the aftermath of debt obligations which led to so much distrust and economic dislocations after the First World War. It allowed us in that bleak December of 1941 to join with allies better equipped and more powerful because of our aid, and it was because of the earlier British war orders and Lend-Lease that industry and agriculture within the United States were already moving on a war basis. Lend-Lease was a practical measure. We could not say after declaring war that:

We’ve got the ships,

We’ve got the guns

and the airplanes, the tanks and all else, but we did have the plants to build them on a scale never before realized, and we had the men and we had “the money too.”

There was another consideration in developing the war industries in the United States that was important and understood. The German war industries were based on machine tools. They were the foundation for their industrial war machine. The industry in the United States that had done most in using machine tools to develop mechanized output was the automobile industry. The selection by the President of William S. Knudsen from the automotive industry was proof of that understanding. The contribution made by Knudsen to modernize industry through the intelligent use of machine tools and their directed allocations had much to do with the phenomenal production that amazed our allies and dismayed our enemies.

All this practical side of war reminded me of General Grant’s messages to the War Department when he made his way down the Ohio River. He was forever writing about mules and wagons and shoes for his soldiers, while other generals who were doing less fighting were discussing tactics and Jomini{6} and all the jargon of theoretical warfare.

And then I thought of George Marshall. Grant would have comprehended the man—this tall figure who could grasp the total reach of war with practicality, imagination, and global-mindedness.

I loved the courtesy he showed to General Pershing, his old commander. You did not need to be told that he would have the courage to pick a lieutenant colonel, Dwight D. Eisenhower, and put him in command of the European Theater of Operations, or that he would generously support General MacArthur, who had once been his superior, as the Commander-in-Chief of the Pacific.

I remember Churchill turning to me toward the end of the war and saying, “Perhaps he was the greatest Roman of them all.” This man knew the art of modern war, and what we owe to him future generations will measure to his credit long after we are gone.

When I left college I studied with General Conger, who was afterwards head of G–2 at Chaumont under General Pershing. He taught me much about war and gave me a deep respect for men who knew the art of war. It was from him that I learned what fearless and intelligent leadership meant to fighting men in the battlefield. It was he who, after the Agadir affair in 1911, explained to me that when the Germans finished the Kiel Canal they would in all probability find some incident on which to make war, and begin their march toward the Mediterranean in order to build up a great central European empire.

When I asked Conger if he could name the controlling factors in late 1914, he thought for a minute and then said: “Yes, there are three: the French Army, the British Navy, and the Allied Press. The Press will make clear the issues and that will eventually bring us into the war and ensure the defeat of the Central Powers.”

General Marshall has told me that when he himself was a young man Conger was one of the best minds in the army. After leaving college and while I was still working with Conger, I spent two summers in the Shenandoah Valley studying Stonewall Jackson’s campaigns. It was because Conger had convinced me that you could not make a good officer in less than seven years that I paid my own way to Paris and enlisted as a private in the American Expeditionary Force. He did not approve of my judgment on that, but he liked my doing it.

Conger taught me the structure of modern war; the basic things that were needed to make war—manpower, the output of factories, raw materials, foodstuffs, science, and even psychological warfare, when in those days few people had heard of psychological warfare. He was one of our greatest authorities on Prussian militarism.

Although Conger’s teaching never made an amateur strategist of me, it was because of what he taught me that, while living in Europe before this war, I became acutely aware of the malignance of Nazi political power and its military strength, and realized that the combination would once again threaten the peace of the world.

After Munich, when the Germans invaded Czechoslovakia, the British Government quickly recognized that it must adopt a war economy. The Johnson Act, which forbade borrowing from the United States by countries which had not repaid loans made in the last war, was still on the statute books of the United States. Mr. Chamberlain, then Prime Minister, took this legislation seriously and expected little help from the United States. He showed this when he failed to support Mr. Roosevelt’s suggestion of January 12, 1938, for the creation of a working committee of ten nations, representative of all regions of the world to elaborate a clear-cut agenda to establish a basis for world agreement to maintain the peace. When the President secretly sounded out the Prime Minister, Mr. Chamberlain’s reply was “in the nature of a douche of cold water.”{7} The President had hoped that the proposal would lend impetus to the efforts of Great Britain and France to prevent any further deterioration in European affairs. He believed that, even if the major Powers of Europe, including the Soviet Union, did not succeed in making any progress towards understanding, the United States would at least have obtained the support of all Governments, except the Berlin-Rome Axis, in this effort to maintain world peace. Unfortunately the Chamberlain Cabinet was not the Churchill Cabinet.

Mr. Chamberlain later showed his prejudice against Russia when he refused to let Eden or other ranking officials attend the Moscow Conference in 1939.

But whether or not one agrees with Mr. Chamberlain’s policy of appeasement, it is only fair to recognize that both he and Daladier had the support of many of their people when they met with Hitler and Mussolini and surrendered the Sudetenland to Germany in October of 1938.

The four Powers, on Hitler’s insistence, had excluded the representatives of both Czechoslovakia and Russia from the Munich Conference. The fatal weakness of that decision was not only in misjudging the intent and character of Hitler and Mussolini, but also in the fact that the action taken broke the Protocols of Mutual Assistance under which France and Russia, and Russia and Czechoslovakia, had pledged themselves to come to each other’s aid in a war of defense. Munich wiped out the hope of an Eastern allied front. This put in jeopardy the possibility of holding an allied Western front against the powerful and prepared armies of the Axis. I so informed the President.

In writing of Mr. Chamberlain, it is interesting to note two paragraphs spoken by Winston Churchill to the British Parliaments, when he paid a last tribute to this man with whose policies he had so fundamentally disagreed:

It fell to Neville Chamberlain in one of the supreme crises of the world to be contradicted by events, to be disappointed in his hopes, and to be deceived and cheated by a wicked man. But what were these hopes in which he was disappointed? What were these wishes in which he was frustrated? What was that faith which was abused? They were surely among the most noble and benevolent instincts of the human heart—the love of peace, the pursuit of peace, even at great peril, and certainly to the utter disdain of popularity or clamour.

And again:

When, contrary to all his hopes, beliefs, and exertions, the war came upon him and, when, as he himself said, all that he had worked for was shattered, there was no man more resolved to pursue the unsought quarrel to the death.

These are revealing statements that show the heart and the untroubled fairness of the man who spoke them.

It was said by some that “Churchill enjoyed the war.” No blacker lie was ever spoken. No one could have seen him in the dark days of the war, as I did, and ever doubt his suffering or his caring. Someone asked Mrs. Churchill in 1936 if she thought her husband would ever be Prime Minister. Her answer was, “No, unless some great disaster were to sweep the country, and no one could wish for that.”

I have been told that Mr. Chamberlain’s military advisers forecast a three years’ war. With unusual skill he worked out the balance of annual tax contributions in relation to internal borrowings, but his external supply requirements which called for foreign exchange payments were based not only on maintaining existing trade balances, but on a further expansion of foreign trade. The fallacy of this latter half of his program lay in the limited manpower at the command of the British. Sir William Beveridge, when I was talking with him in 1941, stated the relative position: “The British Commonwealth’s strength in manpower is seventy-five million, the Germans have eighty million, the Italians forty million, and the two in combination control the supporting output of some two hundred million allied or subjugated people.”

When I was in Switzerland, one of our abler statisticians at the International Labor Office explained to me that when the Nazis came into power the total annual earnings of the German people ranged between thirty-seven and thirty-eight billion marks, but that after they had established their full employment scheme, which called for arbitrary assignment to work jobs and a longer work day, there was a gradual increase of total earnings and that production for civilian use was stabilized at approximately forty-two billion, where it was pegged. This permitted a moderate increase in the standard of living, a fact which was noticeable in the beginnings of the Axis totalitarian régimes. It represented the meager material advantage that went with the surrender of freedom to select jobs, of longer hours of work under compulsion. Eventually total annual earnings increased to over eighty billion marks per annum. All of the surplus was devoted to armaments, none for the further improvement of the general welfare. The barter system was introduced in order to ensure savings of foreign exchange and to permit accumulation of gold. An example of this was the purchase of the Bulgarian tobacco crop in exchange for furniture and other articles manufactured by German labor. The tobacco was not consumed in Germany, but sold to Belgium for gold. Accumulated purchasing power in gold and foreign exchange was used to build up military strategic stockpiles of materials which were not obtainable in Germany or Austria, or which were in short supply. This included wolfram, magnesium, copper, and other war essentials, some less obvious, which could then be bought at reasonable prices on the world markets. Just prior to the war, and during the early periods of war before the Allied countries had developed their economic warfare organizations, there was considerable strategic counter-buying and bartering. The important factors in all this relate to the internal economy of a country and the necessity for foreign exchange.

In Britain the accumulated savings in holdings of outside securities and gold balances, with the limited outside areas for borrowings, could not realize sufficient dollar purchasing power, or other foreign exchange, to finance the war; but on the other hand increasing foreign trade meant the continued absorption of millions of men and women engaged to supply goods for foreign markets and tied up to merchant tonnage.

The heavy losses of merchant ships by submarine, raiders, and enemy aircraft and the extended patrol of the British Navy, with the resulting inability to protect convoys adequately, were felt early in the war. A consequence of these losses was the need for additional agricultural labor to increase domestic production because of the reduction of available tonnage for food imports.

The loss in the Dunkirk retreat of all British war material that had been shipped to France placed British home defense in a perilous position. It was then that the King asked his people to turn in their shotguns; I gave what aid I could to further the shipment of a million rifles from America to arm the Home Guard. It is interesting to remember that it was at this same time that one saw chalked up over the news-stands and everywhere the simple words, “There will always be an England.” This undramatic resolution, this complete unwillingness to admit defeat which I saw in the people was matched in their leaders.

The s...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- Letter from Grosvenor Square

- Appointment

- Arrival and Base Lease Agreement

- The Battle of Britain and Bombings

- The Embassy

- Eden and the Foreign Office

- Differences Between the Two Governments

- Lend-Lease and Foreign Exchange

- Contacts and Travels

- Invasion of Russia and Atlantic Charter

- British Home Front

- The Battle Front

- Pearl Harbor

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER