![]()

Chapter 1—THE EXPANSIONIST SETTING: 1844

§1

On Saturday evening, February 19, 1848, there occurred in the city of Washington a simple drama with few characters, but of huge portent to the nation. Shortly after dark a tired, though lithe and vigorous, man of frontier qualities reached the capital. Scarcely two weeks before, he had left Mexico City and had moved quickly downward through mountain passes to Vera Cruz. Ten days later his ship, the Iris, discharged him at Mobile. From there James Freaner, the noted “Mustang” of the New Orleans Delta, hastened northward to his destination. He delivered two letters at the Washington home of Mrs. Nicholas P. Trist and then sought out the residence of the Secretary of State, James Buchanan.{1} In his baggage was the recently negotiated Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo.

This memorable document would shortly convey to the United States the Mexican provinces of California and New Mexico. It would, therefore, complete the process of American expansion to the Pacific which two years earlier had achieved its first notable triumph in the Oregon Treaty. This dual diplomatic success of the James K. Polk administration effected the consummation of but a single purpose. Together these two treaties carried the American tide to a 1,300-mile frontage on the western sea, which included the harbors of Puget Sound, San Francisco, and San Diego.

That generation which elected Polk to the presidency built an empire to the Pacific. Whatever its immediate impulse, this conquest of the continent had foundations sturdily formed through half a century. War and diplomacy filled only the final stage. Earlier Americans had given that policy purpose as well as substance—rugged frontiersmen who had penetrated the most awesome wilderness of North America and sweaty pioneers pushing out along deepening trails, bringing American ways to the valleys of the Willamette and the Sacramento. These men, like transgressors, had found the way hard. More remote in space and time were dour Yankee seamen who cruised across the Atlantic horizon in a vast pincers movement of ten thousand miles in search of markets, sea lanes, and ports of call in the north Pacific. These men called to mind spacious harbors along Pacific shores and markets a hemisphere away—Java, Manila, Singapore, Canton, and Shanghai. Subjugation of the continent was a common endeavor, belonging neither to section nor party.

Thomas Jefferson’s purchase of Louisiana, to Henry Adams “an event so portentous as to defy measurement,” had implied that the United States would become a great continental power. Thereafter geographical predestination alone convinced numerous British and American writers that the nation would one day reach the Pacific. Some, indeed, had regarded the prospect with considerable pleasure.{2} Not until the forties, however, did the Americans approach the high point of their expansive power when they would propel the course of empire to its long-expected fulfilment.

The stage was well set. Polk’s America was as restless as a caged leopard and as charged with latent energy. In twenty years the American people had broken tens of thousands of new acres to the plow. They had created new cities where a wilderness had held sway. From New England to Pennsylvania and reaching on into the Ohio Valley an industrial revolution was multiplying the productive resources of the United States. Previous uncertainty over the nation’s future was rapidly crumbling before an unprecedented vigor and self-confidence. The forties were a spacious decade. From the radiating power of American industry and commerce and the strength of a pioneering movement the distant Pacific shores would not escape.

Individual enterprise created the first centripetal force. Afterward came group ambitions and national effort, terminating in the final triumphant progression of American arms from Monterey and Buena Vista to Contreras, Churubusco, and Molino del Rey. Many streams of adventure, political maneuvering, and administrative policy played a role in the growth of the republic. But the determining factor that charted the course of the American nation across the continent to the Pacific was the pursuit of commercial empire. Through every stage of this westward extension blew the west wind and resounded the crash of heavy surf on a bold and distant shore.

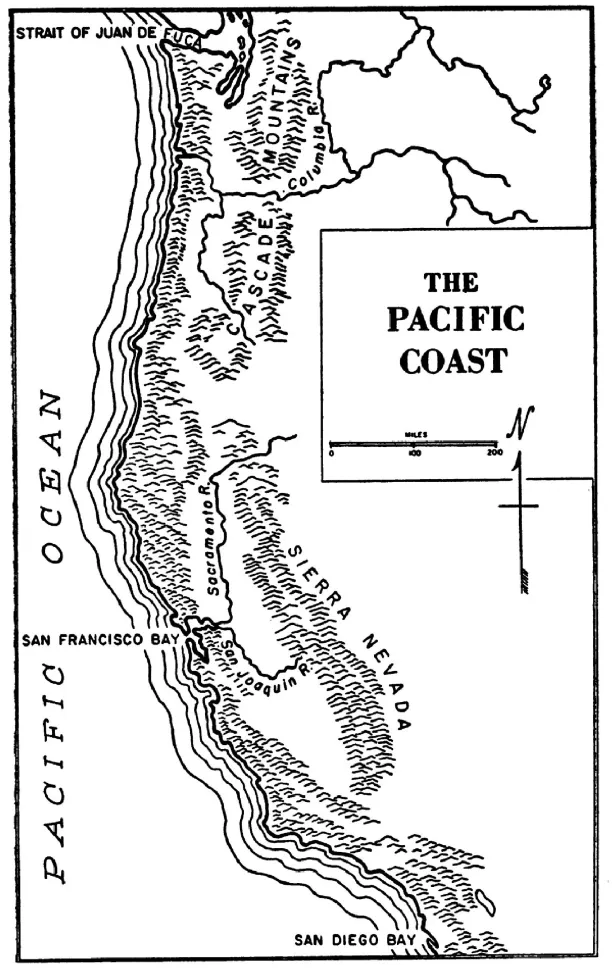

It was a forbidding coast that stretched and twisted from Juan de Fuca Strait to San Diego Bay. Through most of this length offshore mountain ranges crowded the narrow coastal plains or pushed them completely into the sea, leaving threadlike beaches hemmed by jutting cliffs. Only one river, the Columbia, reached deeply enough into the interior to become a maritime port. Nature had confined her lavishness in the creation of harbors along this shore line to three locations. At the Strait of Fuca she had severed the mountains completely, permitting the sea to inundate the vast reaches of Puget Sound with its myriad of islands, inlets, bays, and harbors.

Eight hundred miles to the south was the second cut, the Golden Gate. Here she had formed a harbor of hundreds of square miles behind the lofty outer ranges and created an access to the large inland valleys of the Sacramento and San Joaquin. Far to the south where the coastal range recedes from the shore, nature provided the third major port of the Pacific coast, San Diego Bay, formed by a long, low limb of land extending westward and northward to enclose the harbor’s land-locked waters. Empire-building in the forties secured frontage on the western sea that encompassed precisely these three harbors, suggesting at the outset a large measure of commercial particularism in the underlying American purpose.

As late as 1844 only the sea gave real significance to regions bordering the Pacific. Over its trackless routes had passed Spanish, British, and American seamen who in a span of two centuries had carefully charted the coast’s inlets and harbors. From that astonishing array of mariners loom such names as Juan de la Fuca, whose name appears gratuitously on a strait he never sailed, Sir Francis Drake, Pedro de Unamuno, Sebastian Vizcaino, James Cook, Robert Gray, and George Vancouver. Countless seamen had known this coast and had known it well before Meriwether Lewis and William Clark traversed the continent and stood breathless at the mouth of the Columbia. Yankee merchants had plied the coastal waters in search of sea otter and hides decades before American pioneers appeared in neighboring valleys. First love of Oregon and California was the broad Pacific; for New England seamen it was the tiny strip of coast hugging the sea.

Through fifty years Yankee mariners had anchored that strip to the larger world of the Pacific. Like the Spaniards who had sailed the famed Manila galleon, they had demonstrated the profitable and natural relationship that existed between the Pacific coast of North America and the great markets of the Orient. In the forties New England was invading the distant ocean with renewed vigor, but the transoceanic ties of the Pacific lay even heavier on the minds of commercial expansionists. What mattered was not the reality of that commerce in the mid-forties, but its unlimited future for that nation which could control the sea lanes of the north Pacific.

![]()

§2

Boston in 1844 was entering a new era of commercial greatness. Her teeming population, now surpassing the hundred thousand mark, still supported a volume of shipping second only to New York. Never before had her wharves been so congested, her harbor so crowded. During the thirties Boston had averaged fifteen hundred vessels a year; throughout 1844 her average reached fifteen a day. Few major markets of the world were excluded from her vast trading empire, but her contacts with the Far East still loomed high in her prosperity.{3} East-India merchants continued to enjoy a special prestige in New England seaport towns, and an office on Boston’s India Wharf still conferred more distinction than ownership of a cotton textile mill.

Boston merchants had successfully invaded all key ports of Southeast Asia. At Canton the New England firm of Russell & Company conducted the bulk of America’s share of the China trade. British goods pouring into the Orient after 1835 increased the competition for markets and reduced American sales. Thereafter United States imports of silks, teas, and coffee tended to create enormous trade balances against New England and New York merchants. The heavy British sale of Indian opium created a demand at Canton for bills of credit on London; these the American traders supplied.

China itself was assuming new commercial significance. After the First Opium War of 1842 the British forced China to open four additional ports to British vessels. Quickly President John Tyler dispatched Caleb Cushing, a Newburyport, Massachusetts, lawyer closely identified with the Canton trade, to China to secure like concessions for the United States. In the Treaty of Wanghia, which Cushing negotiated in 1844, American merchantmen gained admission to five Chinese ports, including Canton and Shanghai. This treaty broke the monopoly of the Hong merchants of China, a privileged class who held licenses to conduct that nation’s foreign trade and serve as keepers of Canton’s foreign community.{4} For years this group had harassed foreign merchants with annoying exactions and heavy port charges. This treaty marked the first time in six decades that United States trade with China had the benefit of American diplomacy. Suddenly to merchants, travelers, and politicians the markets of the Orient seemed staggering in their potentialities.{5}

Hawaii was a piece of New England in mid-Pacific. Boston merchants had linked the trade of these islands with California, Canton, and the south Pacific. “Honolulu,” writes Samuel E. Morison, “with whalemen and merchant sailors rolling through its streets, shops fitted with Lowell shirtings, New England rum and Yankee notions, orthodox missionaries living in frame houses brought around the Horn, and a neoclassic meeting-house built out of coral blocks, was becoming as Yankee as New Bedford.”{6}

New England merchants had brought Oregon into the China trade as early as 1787, when they commissioned Captain Robert Gray and the Columbia to visit the Oregon coast in search of sea-otter skins. From that moment the trade grew to impressive proportions almost purely by Boston enterprise. Looming large in Boston’s success was the tough shipmaster William Sturgis, who entered the trade early. With John Bryant of Boston he formed the firm of Bryant & Sturgis, which revived and dominated the Northwest fur trade after the War of 1812. Until the thirties this high road of Boston commerce offered profits and adventure—rounding the Horn, bartering for fur in Oregon, trading for tea and silk in Canton.

This trade bound that stretch of coast from the Columbia to the Strait of Fuca to the hearts of Yankee seamen. By the forties the traffic had disappeared.{7} Hudson’s Bay, the Northwest Fur Company, St. Louis fur traders, and Russians moving southward from Alaska created too much competition and drove fur prices too high. After 1837 only occasional New England ships skirted the coast in search of the disappearing skins. Boston’s old Northwest trade was history, but its impact on the New England conscience persisted.

California likewise had captured the Yankee imagination. Long before the Mexican Republic opened these ports to world shipping, Boston vessels had frequented these coasts in search of sea otter. With the news of Mexican independence in 1822, Boston mercantile houses dispatched their ships to acquire California hides. Thereafter hides for the New England boot and shoe industry jammed the holds of returning Boston merchantmen.

Bryant & Sturgis entered the hide trade with their Sachem in 1822 and dominated it for the next twenty years. When Alfred Robinson, later to represent the company at Santa Barbara, arrived aboard their Brookline in 1829, the trade was firmly established. For another decade this house did a thriving business, keeping one or more ships active along the California coast at all times. In the twenty-year period Bryant & Sturgis exported about a half million hides, or about four fifths of the total.{8} The Bay State’s exciting commerce with California, which qui...