- 494 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

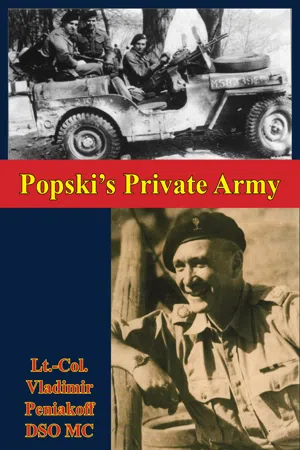

Popski's Private Army

About this book

In October 1942, Vladimir Peniakoff (nicknamed Popski) formed his own elite fighting force in the North African desert. Over the next year 'Popski's Private Army' carried out a series of daring raids behind the German lines that were truly spectacular—freeing prisoners, destroying installations, spreading alarm. This, one of the classic memoirs of the Second World War, is their story.

'A story of adventure...which has no rival in the literature of any war.'—DAILY EXPRESS

'This is certainly among the best of war books...splendid writing.'—THE OBSERVER

'One of the small handful of really first-class war books. A superb story of adventure told masterfully, brilliantly.'—EVENING STANDARD

'His courage, resourcefulness and qualities of leadership deservedly gained him a high reputation. He has now shown that he also possesses unusual literary talent.'—THE DAILY TELEGRAPH

'A story of adventure...which has no rival in the literature of any war.'—DAILY EXPRESS

'This is certainly among the best of war books...splendid writing.'—THE OBSERVER

'One of the small handful of really first-class war books. A superb story of adventure told masterfully, brilliantly.'—EVENING STANDARD

'His courage, resourcefulness and qualities of leadership deservedly gained him a high reputation. He has now shown that he also possesses unusual literary talent.'—THE DAILY TELEGRAPH

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART ONE—ALONE

CHAPTER I—DEFEAT OF THE LEVANT

AFTER I had settled in Egypt I kept few ties with Belgium, a small, dull country, I thought, with which I was bored. Furthermore I had belonged in that country to a clique of highbrows with whom it had been fashionable (and, funnily, still is, as I have recently discovered) to deride the Belgians for being a loutish and inferior breed. I have changed my mind now about that country, but for years I seldom visited Belgium and neglected most of the friends I had.

Living in Egypt I was automatically incorporated in the local European communities, all more or less Easternized in spite of their British, French, German, Italian or Greek origin. This half million of non-Egyptians are elaborately stratified. Going by outward appearances I suppose my label should have been as follows: ‘Belgian engineer. First generation in Egypt. Mixes more with the British than with his own Belgian community, yet practises no kind of sport. Does not play bridge. At home also in the French and Italian colonies. Does not cultivate the Egyptian Pashas and is not a member of the Mohamed Ali Club. Unlikely to reach eminence in the local business world’.

In fact the Levantine atmosphere that pervades the European communities in Egypt made me uneasy and slightly scared of its debilitating influence: as the years went by I anxiously watched myself, expecting to find the symptoms of rot—the mixing of languages and the gesticulating hands.

Local Europeans, Levantines and Westernized Egyptians lead a dreary life. Endeavour is limited to fierce, unimaginative money-making and the more unrewarding forms of vanity. The thrills of love are provided by a season ticket at the brothel and mechanical affairs with the dry, metallic, coldly lecherous wives of your friends. No hobbies. Games are played, to be sure, out of snobbishness, copying the English. Adventure is provided by daily sessions of bridge, rummy or poker, and gambling on the Cotton Exchange. Books are valued in a way: a wealthy Armenian cigarette-maker caused an upheaval when he provided his new flat in Gezirah with a library. I was invited to inspect impressive bookshelves: the bindings were gay and suspiciously new: in their thousands, they covered the walls from floor to ceiling. One panel was green, another blue, another antique calf. On inspection I discovered five sets of the complete works of Victor Hugo, three of Balzac, seven of Paul Bourget, four of René Bazin. The antique calf were fakes, not books at all but boxes cunningly fitted with backs cut off old books. Anyhow the owner, who speaks fluently (and simultaneously) eight languages, is illiterate.

This way of life is so boring that I never could understand why it is valued at all: indeed the death of friends and relatives is suffered with the regulation amount of tears and hysterics but otherwise with perfect equanimity. But when it comes to personal danger: what agonies of fear, and orgies of self-pity! Cowardice is boasted of and praised as a virtue—the main, the fundamental virtue, the one that keeps going these poor cardboard lives. The wise man is the one who experiences most fears, for thus he can protect himself against more dangers. In fact these shams, who spend their lives copying people they don’t understand, have only one feeling that is genuine: fear. They are terrified of physical pain, of disease, of losing money, of losing face, of accidents, of discomfort, of hard work and all; they are constantly scared and they like it; revel in it. And why shouldn’t they, the poor wretches? The fear of death is the only real motive they have for going on living.

I am by nature cautious; running deliberately into danger goes against the grain. But if I can enjoy taking risks and don’t mind physical hardship I believe I owe it to the puppets amongst whom I lived for sixteen years. It seemed natural to strive after a way of life opposed to theirs.

Levantines are only a nasty scum covering the great mass of fellaheen, the peasants on whom they prey. I liked the latter, simple folks with their roots deep in the soil—so deep indeed that they could hardly be thought to emerge at all from their Nile mud. I worked with them, understood them and spoke their language: in return I received friendliness and devotion. In a land of sham, pretentiousness and half-baked aspirations they were genuine: kindly, human, ignorant, hard-working and unaffected. But I wouldn’t try to live as one of them, the poor, starved, cringing, cowardly wretches.

I had more respect for the scanty Badawin who, in small numbers, still roam the deserts of Egypt. Weak offspring of the masters of the world, they retain a smouldering memory of the Arab conquest and they still maintain a nearly dissolved link with their parent tribes in Arabia. Poor and all but extinct, roving nomads like their forefathers, they are still acknowledged as masters by their fellaheen neighbours, who fear them without reason, for there is no strength in them.

It grieved me to find a noble race so fallen and I attempted to build them up into authentic Arab characters, an effort of constructive imagination which owed much to Doughty’s Arabia Deserta.

From 1925 to 1928 I worked in the sugar-mill at Nag Hamadi north of Luxor, in Upper Egypt. For eight months in the year, between the sugar seasons, my duties were light and gave me abundant leisure for Palgrave, Burton, Doughty, Lawrence and Gertrude Bell, writers on Arabian travel; slowly and at second hand I fell under the spell of the Arabs.{1} My mind gradually set on Arabian discovery, and travel in Arabia became my ultimate aim. At that time neither Philby, nor Bertram Thomas, nor Ingram had yet made their great journeys in southern Arabia, nor had Ibn Sa’ud been taken over then by the oil interest; thus big rewards could still be picked up by the explorer in Arabia.

With these plans in mind I discovered Haj Khalil and I undertook to train him in the traditions of his forefathers. He was only a petty sheikh of twenty Badawin tents, owner of a few acres of sugar-cane on the edge of the desert, and a small-scale labour contractor for the sugar-mill, but he had in him noble stirrings and the seed of greatness. Now settled in comfortable middle age, he had in his youth ridden to and fro to the Sudan driving camels for sale to Egypt, and had considerable desert lore. He and his brother Mifla, an uncouth camel-boy, were my guides as we rode our camels in the desert near Nag Hamadi on short trips of four or five days. I learnt then the rudiments of life in the desert: landmarks, how to read tracks, where water can be found, pastures, the care of camels and the courtesies of the nomads. Khalil is the only Arab I have met who could explain and teach desert lore. On one of our early trips he made me dump my topee—a very uncomfortable headgear when riding a camel—behind a rock in a wadi. A few days later, coming down the same wadi on our way back, he called out: “Where is your large hat?” and laughed when I had to admit I had no idea. He said the wadi would next take a bend to the north-east, then sweep round to north-west—then three small bushes in a row—a rock shaped like a coffee-cup—a gravel ridge about as high as the palm of my hand—a cave—a boulder like a camel’s head, and behind the boulder: my topee. Thus was I trained to memorize landmarks.

In return for his tuition I taught him the ancestry of his tribe, the Rasheidis, who they were related to in the Hejaz and how they were an offshoot of the Qoreish, the tribe of the Prophet. He was not entirely ignorant of these matters, having been on the pilgrimage and a guest of his brethren in the Hejaz, but until I came, he had not thought much of it, being more concerned to push himself as a business man with the French who ran our sugar-mill than to revive the traditions of his decayed Badawin. Insidiously I diverted his mind to things other than an ambition to cut a fine figure as a wealthy village omdah and put his mind to other things. I told him of the deeds of Sherif Hussein’s Arab army in the late war under Lawrence and the great battles they fought as allies of the English King. Haj Khalil was a true Badu, with a feeling for romantic situations and with political ambitions; he was fired with the pride of his race, but as there were no opportunities for him to shine in battle he had to be content to set about and make himself the leader of the scattered Badawin who pastured their meagre flocks in the mountains between the Nile and the Red Sea.

In this, with my backing, he succeeded very well, and when we entertained our guests, the ragged, bearded visitors from the desert judged him a true sheikh of the Arabs, in his golden headband and white robes and with his generous hospitality of the coffee-cups. For my own role in the pageant they couldn’t find a place in their tradition; the legend of the great English travellers to Arabia had not reached them from across the Red Sea; but they were not embarrassed, as, in spite of their destitution, they had enough pride left to take for granted the flattering attentions of a foreigner and an infidel.

The situation was farcical because Haj Khalil, as an Arab sheikh in the grand tradition, was phoney—his desert subjects were no more than gipsies, and what was I, as an explorer, but a week-end tripper? But nobody took things too seriously: the Arabs were flattered, gained in self-respect and, no doubt, were able to turn to practical advantage in their dealings with the fellaheen their enhanced prestige and their greater cohesion. For my part, I was learning to handle the nomad Arabs safely, at home, so to speak, and in such a manner that mistakes were of no consequence. I could look forward to setting out on my Arabian journeys, when the time came, with some confidence and without being too green.

Although I knew I would someday break my ties, for the time being I refrained from doing so, not being ready yet. So I went about my jobs, first in a sugar-mill, then in a sugar refinery (which stands one step higher in the industrial hierarchy), and for several years I pursued the ordinary activities of industry and, on my yearly leave, the polite pleasures of European travel.

CHAPTER II—PLAY WITH THE DESERT

IN 19301 transferred to the sugar refinery at Hawamdiah, outside Cairo. A refinery, unlike a sugar-mill, works not just four months, but the whole year round: my leisure was now limited to week-ends and occasional holidays, and consequently I had little time to spare for Arabs and desert. Also I had exhausted the possibilities of make-believe in this connection.

I took up flying and on many Sunday mornings I sat in the Almaza flying club waiting for the Egyptian instructor to turn up: for some mysterious reason he was always late, but I quite often got my twenty minutes’ tuition. I eventually qualified for an ‘A’ licence after sixteen hours in the air and one hundred and twenty hours in the club-house. Later I occasionally flew to Alexandria, Port Said or Miniah, but without much real pleasure because flying is a dull business. There is an exhilaration in the first solo flights and in the few stunts which the beginner is taught to do; cross-country flying on the other hand is very much like driving a tram, especially in Egypt, where the weather is always clear and map-reading presents no problems.

In the early ‘thirties I heard about a Major Bagnold{2} and his friends who were making motor journeys in the desert. They had reached the Gilf el Kebir and Oweinat, where Egypt, Sudan and Cyrenaica meet, 680 miles from Cairo and over 300 miles from Kharga Oasis, the nearest supply point. They had penetrated the Egyptian Sand Sea and altogether they had covered thousands of miles in the Western Desert in Ford cars. They navigated with sun compasses, used theodolites and wireless sets to fix their position by the stars, and they drove over rocks and sand dunes which had been considered impassable to motor vehicles.

Here was something new in desert travel, and I experimented on my own to find out how far and how safely I could go with a single car.

I had a Ford two-seater that I converted into a box-body truck fitted with balloon tyres: this was the Pisspot I have mentioned before and it had travelled over 120,000 miles when it came to a sticky end at Mersa Matruh in the second year of the war.

With a circular protractor, a disk of ivory from the Muski in Cairo, a knitting-needle and an aluminium frame, I got the Refinery workshop to construct a sun compass. The first model, mounted on gimbals with an oil damper to cut down oscillations, proved over-elaborate. However I found I could dispense with gimbals altogether, and the instrument I finally used looked home-made, but it was easy to set and it kept me on my course with sufficient accuracy.

When navigating with a sun compass the azimuth of the sun must be known for every hour of the day, and at any particular time of the year. The appropriate tables being out of print, on the day before going on a trip I had to clamp the sun compass on a bench in the garden and make a note, every half-hour, of the position of the needle’s shadow. It was a long and tedious process but, working thus from the bottom, I found I eventually acquired the simple art of navigation so thoroughly that I ran no risk of making a mistake even if I happened to be tired or flustered. This was important because, travelling alone in the desert with no one to check my navigation, an elementary mistake in the setting of the compass might easily have led to disaster.

I didn’t attempt to build a theodolite.{3} I went to the other extreme and bought in Switzerland a Wilde theodolite, so elaborate and so expensive that the transaction broke me and I had to curtail my rock-climbing holiday and slink back to Egypt. Though I soon found out that a common surveyor’s theodolite would have served me just as well, the pleasure of handling this lovely instrument made up for the climbs I had not been able to make in the Dolomites.

To receive the time signals I used a stop watch and a small, dry-cell, commercial wireless set, an unreliable contraption on which, sometimes, I managed to hear the time pips from Helwan observatory.

Thus equipped, and provided with the Nautical Almanack and the Royal Geographical Society’s Hints to Travellers, I spent many nights struggling with a star chart. At first Vega, Betelgeuse, Aldebaran, Castor and Pollux were seldom where I thought they should be, but in due course they lost their fickleness and kindly turned up in the region of the sky where they were expected. 29° 52’ 10” North and 31° 14’ 20” East was the position of my house in Hawamdiah. At first I was happy if the stars put it within twenty miles and not in mid-Atlantic or in the Gobi Desert: then I became more proficient and got my astrofix within three miles, which was good enough.

For my training in dead-reckoning navigation I plotted on the map a course of 100 miles or so, beginning and ending at features well identified on the map, and then I navigated my truck with sum compass and speedometer as closely as possible along this course. The distance between my objective and the spot at which I actually ended was the measure of the accuracy of my navigation. I once ended up fifty feet to the west of my objective, the doorway of St Sergius Monastery in Wadi Natrun, but that was a fluke: the going had been excellent, I had been specially careful and I had taken nearly two days to cover 120 miles. This coincidence, however, revealed to me how surprisingly accurate careful dead-reckoning navigation can be. Before that lucky hit I had felt that though I had watched very carefully for hours the shadow of a knitting-needle on an ivory plate there was no reason at all why, at the end of a long day’s drive in a featureless desert, I should from the top of the next rise lift a pyramid on the horizon. After that success, however, I gained confidence, and though I might be as much as ten miles out at the end of a difficult run I never thought I was lost.

For a solitary traveller, as I generally was, driving and navigating at the same time is a trying job. Every time the course is altered an entry should be made in the log book and the truck must be stopped while it is done; in broken country or in a winding wadi this may happen every few minutes and the going becomes extremely slow and tedious. In soft sand, where it would be fatal to stop, long stretches of the course may have to be memorized. When the going is very rough, in rocks or amongst boulders, the driver has to concentrate on watching the ground a few yards ahead of his front wheels and never gets a chance of looking at the compass or the speedometer, nor even at any of the larger landmarks which might enable him to keep a rough track of his course. As a result I had a certain difficulty in estimating the course over the sections where accurate readings had not been possible, and I sometimes had to walk back on my tracks for several miles with a hand compass, till I picked up a landmark.

Soft sand was my greatest problem. I became skilful at spotting and avoiding bad patches and at skimming over treacherous surfaces when no detour could be made. When I did get bogged down I had to unload completely, dig and lay planks under the jacked-up rear wheels. Progress was at the rate of a few feet at a time and it once took me a whole day to cover 300 yards. Then the load had to be ferried across and stowed on board. Instead of planks I experimented (without any success) with rope ladders, canvas mats and strips of coconut matting under the wheels. It was Major Bagnold who invented the steel channels which finally solved th...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- Maps

- Illustrations

- FOREWORD

- INTRODUCTION

- PART ONE-ALONE

- PART TWO-THE SENUSSIS

- PART THREE-JAKE EASONSMITH

- PART FOUR-POPSKI’S PRIVATE ARMY

- PART FIVE-ITALIAN PARTISANS

- ROLL OF HONOR

- HONOURS AND AWARDS

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Popski's Private Army by Lt.-Col. Vladimir Peniakoff DSO MC in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.