- 213 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

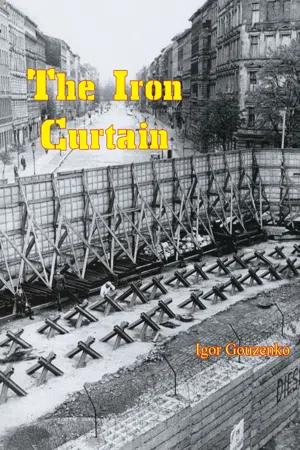

The Iron Curtain

About this book

Originally published in 1948, this book is the autobiographical account of the cipher clerk Igor Gouzenko who defected from the Russian Embassy in Ottawa on 5 September 1945, just three days after war end. In doing so he alerted the Canadian, British and American authorities to the spy rings operating in Canada which were made up of traitorous intellectual professionals and men who belonged to the social and academic establishment of Canada, confirming what Elizabeth Bentley and Whittaker Chambers were telling the FBI in the late 1940's about spy rings in the USA.

A profound and gripping story of one "little man" risking his life for the greater good of protecting the heritage of freedom that many others take for granted..

"We have been impressed with the sincerity of the man, and with the manner in which he gave his evidence, which we have no hesitation in accepting....

"In our opinion Gouzenko by what he has done has rendered great public service to the people of this country, and thereby has placed Canada in his debt."—The Report of the Royal Commission to investigate the facts relating to and the circumstances surrounding the communication, by public officials and other persons in positions of trust of secret and confidential information to agents of a foreign power. June 27, 1946.

A profound and gripping story of one "little man" risking his life for the greater good of protecting the heritage of freedom that many others take for granted..

"We have been impressed with the sincerity of the man, and with the manner in which he gave his evidence, which we have no hesitation in accepting....

"In our opinion Gouzenko by what he has done has rendered great public service to the people of this country, and thereby has placed Canada in his debt."—The Report of the Royal Commission to investigate the facts relating to and the circumstances surrounding the communication, by public officials and other persons in positions of trust of secret and confidential information to agents of a foreign power. June 27, 1946.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER I—The Case of Potekina

ALTHOUGH I never saw her standing on a high cliff laughing down at a stormy sea, as a salty wind whipped her long blonde plaits behind her, that is the way in which I picture Potekina, imagination coloring my boyhood memory.

She was the first girl I noticed as being differently personable than any other girl, but always from an awed, admiring distance until that awful day on the road to a Pioneer camp near Moscow. Suddenly a hand seized mine, and I looked down to find it was Potekina’s. We were both fourteen years old, yet memory portrays her now as a girl standing on the threshold of early womanhood.

Potekina was vivacious, always gay, thin of waist, and a natural leader in sports as well as studies. Even in winter her skin looked tanned, and her ready laugh revealed gleaming white teeth. The other boys would tease her by pulling her blonde plaits, but there was enough of the tomboy in Potekina, and enough of speed in her shapely legs, to chase the teasers around the school yard. Her eyes—they were blue, I think—held a kindliness that seemed out of keeping with her tomboy vigor. But on that particular day those eyes were filled with tears, which both surprised and worried me, overcoming even the thrilling significance of her hand in mine.

Our noisy column of young Pioneers—your equivalent of Boy Scouts and Girl Guides, with a political propaganda angle added—had been halted. Being towards the end of the column we could not see at first what had stopped us. Then gradually, coming from the opposite direction, a slowly moving line of people took shape.

They were the strangest men we had ever seen: dirty, unkempt, with faces an ashen gray. Their clothes were a patternless mess of rags, their feet wrapped in tatters. Among them was one who attracted my attention. His face seemed young, yet the rest of him was old. A piece of cloth, cut out of a bag, and wound around his head like a sort of turban, protected his ears. He had a sparse beard, and a large bluish marl at the top of his nose. His chest had fallen in, and his ribs showed through holes in the shapeless coat that clad him. There was something about him that made me think of a grotesque scarecrow, with a terribly human expression of tiredness and pain. He gave us a little furtive wave with a hand which we noticed was caked with dirtied blood.

“Bread!” he whispered in an oddly croaking voice.

I reached automatically into my kitbag to find a piece but another boy found one first. He handed it to the poor wretch, and the latter chewed away like a dog while his companions looked on ravenously.

All of us were probing for food leftovers when a uniformed girl escort came hurrying down the straggling line. A tight leather belt made her heavy breast bulge in her khaki windbreaker; horn-rimmed spectacles made her pale eyes look like those of a dead fish.

“Don’t dare give them bread!” she shouted excitedly. “They are enemies of the people.”

Other guards in the uniform of the secret police, the NKVD, hurried to the commotion centre and snatched the bread from the young man with the caked blood on his hand. As the bread fell to the ground, a guard stamped it into the dirt of the road. The poor wretch was given a shove. He stumbled, but recovered himself, looking back for a moment to the spot where the bread lay on the ground. His eyes were dull and deep.

It was that gesture, the tired, sick eyes looking back to the road, as if wondering whether it would be worth a gamble to reach for any remaining scraps, that apparently touched Potekina. It was then that I felt her hand in mine, and saw that she was crying.

I recall the strange feeling that came over me in the clear way one does some flashbacks to childhood. There was a curious sensation of pride that she should reach for my hand and not that of one of the bigger boys around us. I knew there was something I should say, something I should do, but what?

There was something evil about what we had seen, but we felt it must be right. Potekina was drying her eyes hurriedly with her sleeve. One of our escorts, a tall young communist of vigorous build, yelled:

“Now then, children! Let’s sing! What the devil are you downhearted about?”

We formed ranks and began to march. Several voices started a song. I tried to join them. Soon the few voices faded into silence. We marched with our own thoughts.

My next memory of Potekina is of a later period. We had graduated from Pioneers to the Komsomol which were the Young Communist Youth. An urgent meeting of the Komsomols of the tenth class was set for four o’clock in the afternoon.

Everybody came. This was something new, with an air of special seriousness about it. Admission was restricted to those presenting a Komsomol membership card.

At exactly four o’clock three men entered the classroom where we were assembled. I knew two of them. They were former pupils of the school who had finished the previous year and were now taking the first course at the Military Academy. One was Zayikin, who was dressed in the uniform of the Academy. He had a bright, energetic face with high cheek-bones, and very short blond hair which stood upright on his rather square-shaped skull. He was studying in the branch of communications. The other was Potapov, also in uniform, but less handsome. A short, plump chap with a tiny uplifted nose, he was in the mechanization branch of the Military Academy. They had been well-known Komsomols. The third man, of medium height and surly expression, wasn’t known to any of us.

The chairman of the Komsomols Committee, a thin student with a long nose, carried on a brief conversation with the stranger, then rose:

“We have one question for today’s meeting. Comrade Gromov, Komsomol organizer from the Central Committee, will address the meeting.”

The stranger bowed, then walked to the front of the platform. He glared at us a full fifteen seconds before speaking. His shoulders were broad and so high that he seemed to have no neck. His thin eyebrows were ruffled into a single line. He stuffed his massive fists into his pockets and took a deep breath:

“Comrades Komsomols!” he began in a heavy, ominous tone. “Today’s meeting was called on the recommendation of the Central Committee of the Komsomol. It was called for the purpose of discussing one question: the question of Komsomol member Potekina.”

My heart skipped a beat. Was I hearing things? Potekina? All heads were turning. I followed their gaze, afraid of what I should see.

Potekina sat huddled in her seat. Her face was white as chalk and her startled eyes were going from Comrade Gromov on the platform back to us.

We had been waiting for anything, but not for this. Only this morning she had been organizing a games party for tomorrow afternoon.

“Potekina!” the chairman was yelling with a severity that frightened us, “Come to the speaker’s table at once!”

She rose slowly to her feet as if in a trance, and walked up to the table where she stood staring at Gromov.

Gromov didn’t even glance her way. Instead he spoke to us.

“It is the opinion of the Central Committee of the Komsomol that this Potekina should be expelled from the Komsomol as an unworthy member who has lost political vigilance and has not been able to uncover an enemy of the people who lived under the same roof with her....”

He paused dramatically, then continued, “The fact that she has not been able to uncover this enemy was not an accident. Maybe she shared the views of her father,....” his voice rose to a shout, “her father who has by now been arrested by the NKVD as an enemy of the people!”

Potekina, her face pale, looked at us as if to read our faces. I felt afraid she would look at me and make some gesture to evoke sympathy.

Her father, we knew, was the financial director of the “Dynamo” plant, the largest electrical equipment manufacturing plant in the Soviet Union, situated in the Proletarsky District of Moscow. Because of his position, Potekina had the benefit of special rations. We had noticed her shoes especially, which were always better than those of her schoolmates.

Comrade Gromov was thundering:

“This girl’s father has been arrested for conspiring to establish a Trotzkyite-Boukharine bloc in the Dynamo plant!”

His voice had risen to a high pitch. The silence that followed was disturbed only by the sound of flies buzzing over the windows. We sat motionless, staring at Potekina. Abruptly, she spoke, her voice a bare whisper, but audible throughout the room.

“I was born in a working-class family,” she said.

Gromov smiled crookedly at her.

“Yes,” she repeated, this time a little frantically, “in a worker’s family.”

“You had better tell us what you and your father used to talk about; what political views you had.”

Potekina seemed a little hysterical: “I did not share his views!”

“Aha!” shouted Gromov triumphantly. “So you knew before that he was a Trotzkyite! Why then, did you not tell the suitable organ? Why did you not disclose an enemy? Eh?” He looked about the audience victoriously.

“You did not understand me aright,” the girl spoke nervously. “I did not share the Trotzkyite views for which you say that he was arrested. I did not know that he held such views. He never discussed them with me. He never....”

“You are getting confused, my dear Potekina,” Gromov interrupted with a grim smile. “First you say you did not share your father’s views, then you say that your father had no such views. You have not been called here to defend your father, who no longer needs a defender.”

Potekina tried to speak again but Gromov waved her to silence.

“It appears to me that we have heard enough of Potekina,” he said with slow emphasis. “She can tell us nothing new. Let the Komsomols now tell us what they know of her.”

We were all silent. Nobody would venture to speak, caught unawares and quite stupefied by the proceedings. We all liked Potekina, lively, energetic, clever at literature and apparently always a staunch patriot. It seemed unthinkable to accuse her of some kind of hostile views. Finally, her best friend, a girl called Zenina, stood up. She was tall, lean, with short dark hair combed like a boy’s, and a stubborn chin.

“I have known Potekina for a long time,” she said, “and have always esteemed her as a successful pupil. She has always been an active Komsomol. I don’t understand why she must be expelled from the Komsomol unless it is because her father has been arrested. That seems unjust because she is a patriot and enjoys the respect of all members of our class. I am sure that other comrades share my views....”

“Speak for yourself,” Gromov cut in harshly. “Don’t speak for others.”

Zenina had a lot of courage. “I do not consider it is necessary to expel Potekina. She is a good member of the Komsomol and will be a good member of the Party.”

From other parts of the room other voices spoke up. “Potekina is a good Komsomol!” “She will be a good member of the Party!” “She had nothing to do with her father’s crime!”

Gromov’s face became dark with anger. He wheeled around and faced Zayikin, the former Komsomol, who was looking worried. Zayikin jumped to his feet.

“Comrades Komsomols! I look at you and wonder if you are really Komsomols or just sucklings. A question of principle is involved and you are acting like a bunch of high-born maiden ladies. A good Komsomol, you say? An excellent pupil, you say? So what? The enemy ...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- CHAPTER I-The Case of Potekina

- CHAPTER II-My Hostages to Freedom

- CHAPTER III-Life in Moscow

- CHAPTER IV-Food, Labor and Education in Soviet Russia

- CHAPTER V-Study and Romance

- CHAPTER VI-Behind the “Curtain”

- CHAPTER VII-Spy Centre

- CHAPTER VIII-The Comintern is “Dissolved”

- CHAPTER IX-Prisoners of War

- CHAPTER X-Anna, My Wife

- CHAPTER XI-The Soviet and the Jew

- CHAPTER XII-Instructions for Abroad

- CHAPTER XIII-Zabotin and Canada

- CHAPTER XIV-Bickering Paradise

- CHAPTER XV-Fifth Column Incorporated

- CHAPTER XVI-Alias Alek

- CHAPTER XVII-A Spy in Parliament

- CHAPTER XVIII-On The Eve

- CHAPTER XIX-Difficult Escape

- POSTSCRIPT

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Iron Curtain by Igor Gouzenko in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Russian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.