![]()

CHAPTER ONE — Troubled Childhood

I

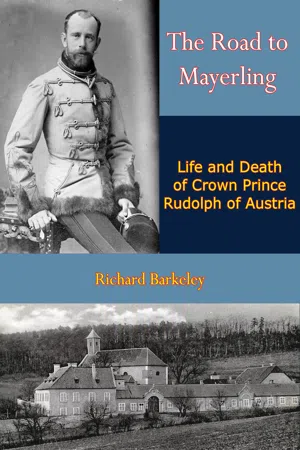

RUDOLPH FRANCIS CHARLES JOSEPH of Hapsburg-Lorraine, Crown Prince of the Austrian Empire, was born on August 21st, 1858, in the Hofburg, the Vienna Imperial Palace. His father, Emperor Francis Joseph I, had just celebrated his twenty-eighth birthday, and his mother, Elisabeth, the beautiful Princess of the Bavarian house of Wittelsbach, was not yet twenty-one. Rudolph was the third child of his parents—the first two had been girls. So one can understand that they were overjoyed at the birth of a son who would perpetuate the line of the Hapsburgs, rulers over the Austrian lands for six centuries. When congratulated on his son’s birth Francis Joseph wept with emotion. He found the baby ‘not exactly beautiful, but well built and strong’. The child, soon after his birth, was appointed a colonel in the Imperial Austrian army, but, in spite of his father’s verdict, he proved to be at first rather weak and required a great deal of care, particularly since his mother was not permitted to feed him herself. To her great regret it was impossible not only because of Court etiquette, but also for medical reasons.

This failure increased her desire to nurse him through his difficult first months, but she met with the resistance of the Emperor’s mother, the Archduchess Sophie, whose strict rule dominated the Court of Vienna. By her orders Elisabeth was for some years prevented from taking part in her children’s upbringing. This enforced rôle of observer was hard for her to bear, particularly as her first daughter had died when only two years old. She was convinced this had been due to the Court physician’s ignorance, which was probably the case. The new-born baby’s weak state must have driven her frantic with anxiety, yet her mother-in-law was adamant, and much as the Emperor was in love with his beautiful wife, especially now after she had borne him a son, obedience to his mother was second nature to him, and her pernicious influence permeated the life of the family as much as that of the state. Thus Elisabeth found no help from her husband in her struggle for her proper share in the care of her tiny son. Sophie, at least for the present, had her way, and it was a Baroness Welden, ‘Wowo’ as the baby soon affectionately called her, who nursed him expertly through his early troubles; throughout his life Rudolph remained fond of her.

A few days after his birth, the most famous German stage of the day, the Vienna Burgtheater, celebrated the event by a gala performance in which the Muse of History was shown sitting among the ruins of the past. With a golden stylo she wrote on a marble slab the date of the child’s birth, and whilst writing said, ‘Here are engraved the year and the day, but the rest of the tablet shall remain empty, for I must have room for his great deeds which, I foresee, will be recorded here’.

II

The nations of Austria attached great hopes to the young child who was to be their future Emperor. The name of Hapsburg had not yet lost its attraction for most of the peoples of the Empire, whatever their language, and they expected the young Prince to make good the shortcomings of his father, who had lost much of their goodwill by the mistakes made in the ten years since his accession.

The Emperor, despite his youth and regardless of earlier promises, had not stopped the rot which had set in under his predecessors. Most of his early advisers had been ill chosen, and he had ruled as an autocrat. Economic conditions had deteriorated, foreign policy had been inept and Austria’s international prestige was extremely low. His subjects were fully aware of this; many, particularly in the Italian-speaking provinces, chafed under Austria’s domination. His ambitious mother, the Archduchess Sophie, directed his political attitude just as she dominated his family life, and her narrow, bigoted clericalism had influenced the malleable youth in his choice of advisers. Nearly all were men entirely unaware of the strength of the forces which they tried to destroy. The revolutions of 1848-49, which had shaken the very foundations of the Empire more than those of any other country, had been suppressed with much bloodshed and—in Hungary—with Russian help. It had been Francis Joseph’s task, while still hardly more than a boy, to establish internal peace after the revolutions, but he had meekly submitted to counsellors who, by their cruelty, particularly towards Hungary, had prevented any healing of wounds. By allowing these men free rein to vent their spirit of vindictiveness, and by his inability to show clemency, he had forfeited the hopes aroused by his succession. Dissatisfaction and disloyalty continued to smoulder beneath the surface, ready to flare into open revolt at the first opportunity. Francis Joseph, before he had reached the age of twenty, had allowed more death warrants to be carried out in his name than probably any other nineteenth-century ruler of a civilised country throughout his life. Even the Tsar, who had helped to suppress the Hungarian revolution, had been shocked at such severity.

Neither the excitable Viennese nor his other subjects had forgotten the Emperor’s earlier shortcomings and they were not yet reconciled to his rule. Thus they all fervently wished that the little boy, now reared under such difficulties, would one day re-establish the bonds of affection broken by his father’s inexperienced stubbornness. They hoped that Rudolph would one day take over the heritage of the Empress Maria Theresa and her son Joseph II, who had a century or so earlier recreated popular affection for the Hapsburgs by their understanding of their peoples’ needs.

When Francis Joseph had first brought the young Elisabeth as his bride to Vienna, her extraordinary beauty had captivated her new subjects’ imagination and they had been prepared to forgive her husband much of the past. But she was extremely shy and reserved. The Viennese not unnaturally wished for opportunities of seeing their Empress, but she refused to appear frequently in public. Although they were well acquainted with her domestic difficulties and knew very well how her mother-in-law—’evil Sophie’ as they called her in their respectless way—turned the young wife’s joys into gall and wormwood, they did not forgive this reticence. Now the Crown Prince was said to resemble his beautiful motherland a new wave of affection for her, too, swept the city.

III

Francis Joseph was not immediately afforded much time to devote to his son. An extremely clumsy foreign policy had landed Austria in a war which she had to fight without an ally, with an incompetent Commander-in-Chief, and without any popular enthusiasm. The King of Sardinia, determined to unify Italy, wanted to incorporate the Italian-speaking provinces of the Austrian Empire, particularly Lombardy, and Napoleon III, Emperor of the French, gave him active support. The Austrian Commander-in-Chief, recommended by the Archduchess Sophie, had shown a complete lack of ability, and his army had been defeated. Now Francis Joseph, for the first and last time in his life, himself took command of his forces. He had not been trained for such a task and his presence in the field perplexed the military commanders. Too unimaginative to realise the consequences of the many death warrants he had signed in earlier years, now seeing before his eyes the dead and dying on the battlefield was a grave shock to him, and he sought to end the war sooner than the military situation required. He had to cede Lombardy, which rankled deeply. To have lost a flourishing, if rebellious, province, and to be defeated by an upstart, a scoundrel, as the Hapsburg considered the Bonaparte to be, caused the young Emperor to survey carefully the situation into which his policy had landed him. It brought home to him the fact that he had not been sufficiently trained for his office, and consequently he laid down rules for his son’s education which even now, nearly a century later, seem sound and reasonable. Rudolph was to be well prepared for his task—better than his father had been.

To draw up a plan for the education of the Crown Prince of the multilingual Hapsburg Empire was no easy task. Apart from the necessity of mastering a number of indigenous languages he had to learn Latin, French and English. Other subjects, too, presented their difficulties: history had to be shown against a multinational background, and most important was the question of how much time was to be allotted to religious teaching, and how much it was to be allowed to overshadow the rest of the curriculum. Francis Joseph was a devout Catholic and had; moreover, by the Concordat of 1855 with the Holy See, handed over to the control of the Church all education in Austria. Yet in respect of his son’s education he showed himself not so obedient to those principles which he considered so important for his peoples’ spiritual welfare. ‘He must not become a free-thinker, but he should be well acquainted with all the conditions and requirements of the modern times’, a memorandum of the Emperor had stated.

IV

By the end of 1859, when in his second year, Rudolph already showed signs of a strong will; if a wish was not immediately fulfilled only his mother or ‘Wowo’ could quieten him. Once, during a meal when he had no appetite, he was coaxed to eat by his uncle the Archduke Charles Ludwig. The boy very seriously asked to be left alone and told his uncle to go away. This the man took as an order from a higher ranking Archduke, and obeyed. The Emperor was overjoyed at any such sign of what he considered to be his son’s individuality.

At the age of four Rudolph went with his father to inspect the Military Academy at Wiener Neustadt, near Vienna. When the students gave the customary three cheers for the Emperor the little boy also waved his hat and shouted ‘hurrah’—and Francis Joseph nearly cried with emotion and was for several minutes unable to speak. But the boy’s ideal was his mother, she was so beautiful. Whenever he saw her in her ball dress he wanted so much to stay with her.

Rudolph’s health caused much anxiety to his parents. In December 1863 he had typhoid fever, and again in the summer of 1864 he fell from a considerable height when climbing a tree and concussion was diagnosed. For months he remained sick, and after his recovery made full use of this accident to get out of any unpleasant task by pretending to have a headache.

In spite of his poor health he very early—when he was hardly four—showed sufficient intelligence to be given lessons in religious knowledge. His first tutor was one of the Court chaplains. Neither he, nor the Head Chaplain, who took over the lessons a few months later, could inspire in their pupil much enthusiasm for the subject.

The choice of his first governor was not a happy one. Count Gondrecourt took over the supervision of the Crown Prince’s education when the boy was six. He was the Archduchess Sophie’s protégé and she considered his apparent piety more important than his qualities as a governor. He lacked entirely any understanding for a child who was then described as being ‘physically and spiritually more developed than children of his age, but very highly strung’.{1} He was a typical Colonel Chinstrap, and his methods might have been suitable for toughening a country yokel recruit, but were criminal for an overbred, sensitive, precocious and excitable child. Yet Gondrecourt knew how to curry favour with bigoted women. Obviously for the Archduchess Sophie’s benefit he stated in a memorandum: ‘The highest duty of the governor is to apply every means to secure that his disciple will never waver in his religious belief’.{2}

Not only did he fail to achieve this aim of firmly establishing Rudolph’s religious convictions, but he actually did great and permanent harm to the child’s personality. His usual drill-ground methods were even intensified as he set to work to ‘educate’ the supersensitive Prince. On one occasion the Emperor, who always rose very early, looked out into the courtyard one morning before settling down to work. He had heard words of command, and, to his painful surprise, discovered that his young son was being drilled in the deep snow by lantern light.

It is not surprising that the delicate boy could not stand such methods. In May 1865 he became seriously ill; although the trouble was probably diphtheria the diagnosis was not unanimous. People at the Court who did not belong to the Archduchess Sophie’s party maintained that Gondrecourt’s crude methods of strengthening the Crown Prince’s weak constitution were responsible. Elisabeth from the beginning had had a poor opinion of his capability as governor. She disliked his unimaginative approach and like others saw in it the reason why Rudolph did not grow stronger, but more and more nervous. Matters came to a head when she learned a little later that the Count had taken the boy to the Lainzer Tiergarten, a game park near Vienna, had pushed him in, shouted ‘A wild boar is coming’, and himself slipped out leaving the frightened child alone. Elisabeth complained to her husband, but Francis Joseph was not yet certain that the governor, whom his mother had so warmly recommended, was altogether unsuitable, or had merely gone too far on this occasion. Although the loss of the war in 1859 had shaken the Emperor’s faith in the wisdom of his mother’s advice, he was not yet prepared to disregard it entirely. But Elisabeth, fighting for her son’s well-being, remained firm. ‘Either Gondrecourt goes or I go’, she told her husband, and when he still wavered lest he should offend his mother, she showed her determination in a letter: ‘I wish to reserve for myself unlimited authority in everything concerning the children, the choice of their entourage, the place of their residence, the complete direction of their education, in one word, all this has to be decided by me alone until the children become of age’.{3}

Only now, realising how determined his wife was in this matter, did the Emperor give way and dismiss Gondrecourt. Rudolph was seven when the new governor, Latour von Thurmberg, was appointed. Although he too had been an officer in the Austrian army, he had also been a civil administrator. He was—within the limits of his time—an instinctive psychologist, an example of the best type of Imperial servant which nineteenth-century Austria had produced. Highly cultured, well read and with artistic discernment, he was entirely devoted to Rudolph and soon the boy was equally devoted to him. Between the two developed a relationship more like that between two friends than between master and pupil, a relationship which lasted far beyond the time of stewardship.

Latour remained throughout his time of office on good terms with both parents, and the mother, aware that her son was now in good hands, made little use of the authority over her children’s education achieved by her ultimatum. Francis Joseph, whatever the demands of his office, always found the time needed to follow his son’s education; he conscientiously read all progress reports submitted by Latour and answered all his frequent memoranda promptly. He did not interfere in any way and only gave a decision when one was requested, but at all times Latour could be assured that the Emperor supported him. This was essential, as the various factions at the Court repeatedly tried to influence the Crown Prince’s education. The Archduchess Sophie particularly took a long time to accept the new governor, if indeed she ever accepted him fully. As late as December 15th, 1868, Latour wrote to Francis Joseph: ‘I go my straight way without regard for anyone. Thereby one does not become popular, but it is the only means of keeping one’s independence at the Court.’

On another occasion he pointed in his criticism directly to female influences, stating in his memorandum that women had the peculiarity of expecting too much of any man who had succeeded in gaining their confidence. The Emperor must have been suffering, too, from attempts at interference, for although usually sparing in his comments, he noted in the margin, ‘Quite right’.

V

Latour had not been in charge for a year when, in the summer of 1866, the war between Aust...