![]()

PART ONE — FINDING THE METAPHOR

CHAPTER I — The Nature of Metaphor

1. Using Metaphor

HOWEVER appropriate in one sense a good metaphor may be, in another sense there is something inappropriate about it. This inappropriateness results from the use of a sign in a sense different from the usual, which use I shall call “sort-crossing.” Such sort-crossing is the first defining feature of metaphor and, according to Aristotle, its genus:

Metaphor (meta-phora) consists in giving the thing a name that belongs to something else; the transference (epi-phora) being either from genus to species, or from species to genus, or from species to species, or on the grounds of analogy.{2}

Thus metaphor is logically indistinguishable from trope, the use of a word or phrase in a sense other than that which is proper to it. Aristotle apparently regarded the features that distinguish metaphor from trope as psychological, but he did not specify them. What these differentiae are, which make the chief problem of metaphor, I shall consider shortly.

Notice how wide Aristotle’s definition is. Metaphor comprehends all those figures that some distinguish as: synecdoche (sort-crossing from genus to species or vice versa, for example, treating the university as of the same sort as a building on the campus, or the division as a battalion or battery); metonymy (giving the thing a name that belongs to an attribute or adjunct, for example, “sceptre” for authority, or “the crown” for the sovereign); catachresis (giving the thing which lacks a proper name a name that belongs to something else, which includes the use of ordinary words in a technical sense, for example, Berkeley’s “idea” and Whitehead’s “point”); and metaphor (giving the thing which already has a proper name a name that belongs to something else on the grounds of analogy, for example, “That utensil!” applied to Mussolini by Churchill, “metal fatigue,” and “Man is a wolf”). Aristotle’s discernment in treating analogical sort-crossing, to which many restrict the name “metaphor,” as only one species of metaphor, is commendable. That the resemblance theory of metaphor is inadequate has been cogently argued by Max Black who concludes that it would be more illuminating to say that in some cases “the metaphor creates the similarity than to say that it formulates some similarity antecedently existing.”{3} Metaphor often is grounded on such similarity but need not be. It might be grounded on revelation.

Wide as Aristotle’s definition is I make it wider. Without stretching his meaning unduly, I interpret his singular “name” to mean either a proper name, a common name, or a description expressible as a phrase, a sentence, or even a book. In which case a more adequate presentation of the defining feature of metaphor I am now considering is made by Gilbert Ryle. Metaphor consists in “the presentation of the facts of one category in the idioms appropriate to another.”{4} As with Aristotle’s definition the fundamental notion expressed here is that of transference from one sort to another or, for short, of sort-crossing. Thus defined, metaphor comprehends some cases of the model and also of the allegory, the parable, and the enigma which, from Aristotle’s point of view, would be cases of extended metaphor, I should point out, however, that although this definition admirably suits my purposes, it is not Ryle’s definition of metaphor at all. It is, indeed, his definition of category-mistake, and is therefore basic to his correction of the dominant modern theory of mind.

The definition is still not wide enough. Some cases of metaphor may not be expressed in words. Again without stretching Aristotle’s meaning unduly, I interpret his “name” to mean a sign or a collection of signs. This will allow artists who “speak” in paint or clay to “speak” in metaphor. Michelangelo, for example, used the figure of Leda with the swan to illustrate being lost in the rapture of physical passion, and the same figure of Leda, only this time without the swan, to illustrate being lost in the agony of dying. It will also allow the concrete physical models of applied scientists, the blackboard diagrams of teachers, the toy blocks of children that may be used to represent the battle of Trafalgar, and the raised eyebrow of the actor that may illustrate the whole situation in the state of Denmark, to be classified as metaphor.

Such an extraordinary extension of the meaning may seem absurd. This, the traditional view, is expressed by W. Bedell Stanford: “If the term metaphor be let apply to every trope of language, to every result of association of ideas and analogical reasoning, to architecture, music, painting, religion, and to all the synthetic processes of art, science, and philosophy, then indeed metaphor will be warred against by metaphor...and how then can its meaning stand?”{5} This objection to the identification of metaphor with trope is, of course, valid. It therefore seems to be valid against Aristotle’s definition and my extension of it which, because they blur needed distinctions, should be discarded. But all that follows is that sort-crossing, by itself, is not enough to define metaphor. Other features are needed. Aristotle probably realized this. Apparently noticing no logical distinction between metaphor and trope, he correctly gave the trope as the genus of metaphor, and then correctly distinguished its various species which were different logical kinds of sort-crossing. But this is where he stopped. Having offered one defining feature, he was desiderating others that constitute a new dimension. Not every sort-crossing is a metaphor, but every sort-crossing is potentially a metaphor. We need this initial width which I now proceed to whittle down.

The use of metaphor involves the pretense that something is the case when it is not. That pretense is involved is only sometimes disclosed by the author. Descartes said: “I have hitherto described this earth, and generally the whole visible world, as if it were merely a machine.”{6} But just as often metaphors come unlabeled. Michelangelo made no meta-sculptural inscription on the base of the sculpture “Night” disclosing that he had borrowed the Leda figure to illustrate the nature of death, although the initiated knew that he had. Nor did Churchill say that he was using the name “utensil” figuratively.

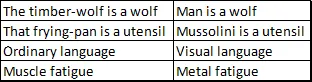

That pretense is involved is not revealed by the grammar. There is no significant difference grammatically between each of these pairs:

Yet I am inclined to say that only the second members involve metaphor. In the examples the two different things or sorts referred to in each pair share the same name, and it is as if they share other things as well. When I say that the timber-wolf is a wolf I am actually giving to timber-wolves a name that belongs to other wolves, and I mean that the timber-wolf is a sort included in the larger sort wolf; or that timber-wolves share with other wolves all the defining properties of “wolf”; or that timber-wolves are included in the denotation of “wolf.” On the other hand, when I say that man is a wolf (metaphorically speaking) I am actually giving him a name shared by all other wolves just as if I believe that he is another sort of wolf like the timber-wolf or the Tasmanian wolf, sharing with them all the defining properties of “wolf,” or sharing with them inclusion in the denotation of “wolf.” But though I give him the same name I do not believe he is another sort of wolf. I only make believe he is. My words are not to be taken literally but only metaphorically. That is, I pretend that something is the case when it is not, and I implicitly ask my audience to do the same.

But more clarity is needed on the matter of what is pretense and what is not. Certainly when I use a metaphor there is no pretense about the name-transference. Man actually shares the name “wolf.” But it is pretense that man is a sort of wolf. However, something besides the name is transferred from wolves to men. I do not merely pretend that man shares the properties of wolves; I intend it. What these properties are I may, but need not, specify. They cannot be all the properties common to wolves, otherwise I should intend that man is actually a wolf. Thus when I say that man is a wolf (metaphorically speaking) I intend that he shares some of the properties of wolves but not enough of them to be classified as an actual wolf—not enough to let him be ranged alongside the timber-wolf and the Tasmanian wolf. Or when I say that vision is a language I intend that vision shares some of the properties of language but not enough to let it be ranged alongside English and French.

Consider, however, the effect of conjoining the metaphors listed above with their corresponding literal expressions:

Men and timber-wolves are wolves

Mussolini and that frying-pan are utensils

Visual and ordinary language

Metal and muscle fatigue

These conjunctions serve to disclose the ambiguity of certain words. When I speak of the timber-and the Tasmanian wolf I refer to two different sorts of wolves by using the word “wolf” in only one sense. But when I speak of the timber-wolf and the man-wolf it is not a case of referring to two different sorts of wolves. This is so because the word “wolf” is being used in two different senses even though it is as it were being used in only one. The two different senses are called the literal and the metaphorical senses of “wolf.” Similar remarks apply to the other examples. It seems then that conjunctions such as these are devices for making us aware of the duality of meaning of one word or sign. Can it be then that awareness of the duality of meaning is the test of using metaphor? But consider some other similar conjunctions:

Seeing the point of the needle and the joke

Smelling of musk and insolence

Clad only in her tiara and an embarrassed expression

A toast to general contentment and General de Gaulle

Such conjunctions reveal the mechanics of the traditional joke that depends upon using the same word in two different senses at once. A common way of treating them is to force the “literal” meaning: to say, for example, that to smell of musk and “My Sin” is to smell of two different sorts of perfume, while to smell of insolence is not to be smelly at all. Moreover, just like the earlier given set, these conjunctions reveal not only the presence of duality of sense but the presence of metaphor, one sense being literal, the other metaphorical. In which case such expressions as “seeing the point of a joke” and “smelling of insolence” are metaphors. But this is to confuse the literal with the physical and to hold that any non-physical sense is metaphorical. Originally the literal may have been nothing but the physical. But it is not so now. There may be many literal senses, only some of which are physical. This seems to be the case here. While we are aware of the many senses in which words like “see,” “general,” etc., may be used, we do not usually consider that one of these senses—the physical—holds a monopoly of the literal sense, the others being figurative. Accordingly, it is more accurate to say that such conjunctions reveal the presence of duality of sense or sort-crossing but not necessarily the presence of metaphor.

It is harder to construct conjunctions producing the same effect with words in which the original—probably physical—sense has been lost to all but classicists:

Comprehend the meaning

Perceive the table

Discourse upon logic

For the same reason it is harder to make metaphors with them. Nevertheless it is possible for the expressions just listed and for those like “see the point of the joke” etc., treated above, to become metaphorical. Awareness of duality of meaning, as we have seen, is not enough to do it. Neither my awareness of my ability to see the point of a needle at the same time as I say that I can see the point of a joke, nor my awareness of my ability to detect the smell of musk at the same time as I say that he came into the room smelling of insolence, is enough to make my assertions metaphorical. Nor, if I am an etymologist, is my awareness of the gross original sense of “comprehend” at the same lime as I say that I comprehend your meaning. In all these cases I am using words in one or other of their literal senses. I am representing the facts of one sort in words that may be equally appropriate to the facts of another. What more then is needed to make these expressions metaphorical?

The answer lies in the as if or make-believe feature already sketched and illustrated. When Descartes says that the world is a machine or when I say with Seneca that man is a wolf, and neither of us intends our assertions to be taken literally but only metaphorically, both of us are aware, first, that we are sort-crossing, that is, representing the facts of one sort in the idioms appropriate to another, or, in other words, of the duality of sense. I say “are aware,” but of course, we must be, otherwise there can be no metaphor. We are aware, secondly, that we are treating the world and man as if they belong to new sorts. We are aware of the duality of sense in “machine” and “wolf,” but we make believe that each has only one sense—that there is no difference in kind, only in degree, between the giant clockwork of nature and the pygmy clockwork of my wrist watch, or between man-wolves and timber-wolves. It is as if the sentences

The world and this clock are machines

and

Men and timber-wolves are wolves

which we both know to be absurd, were meaningful and true. In short, the use of metaphor involves both the awareness of duality of sense and the pretense that the two different senses are one. To Dr. Johnson’s remark that metaphor “gives you two ideas for one,” we need to add that it gives you two ideas as one.

To encompass this new factor Aristotle’s definition must therefore be expanded. Gilbert Ryle offers a still better definition of metaphor: “It represents the facts...as if they belonged to one logical type or category (or range of types of categories), when they actually belong to another.”{7} This greatly illuminates the subject of metaphor because it draws our attention to those two features that I have been stressing, namely sort-crossing or the fusion of different sorts, and the pretense or as if feature. I should again point out, however, that although this definition is about the best definition of metaphor known to me, it is not Ryle’s definition of metaphor at all. It is, indeed, his alternative definition of category-mistake or categorial confusion.

The definition of metaphor now arrived at is based on Aristotle’s. It improves his, first, by widening it to include as potential metaphors any signs possessing duality of meaning; and secondly, by narrowing it to differentiate metaphor from trope, thus satisfying the desideratum in Aristotle’s definition. Moreover, it saves his definition, which is basically correct, first, by retaining his notion that metaphor is the genus of which all the rest are species; and, secondly, by preserving the distinctions between metonymy, synecdoche, and catachresis. But, of course, none of these is properly a metaphor until the as if prescription is filled. All of them have the basic ingredient of sort-crossing or duality of sense, and, to this extent, are all tropes. All of them, however, are potentially metaphors. Any trope can achieve full metaphorho...