- 62 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

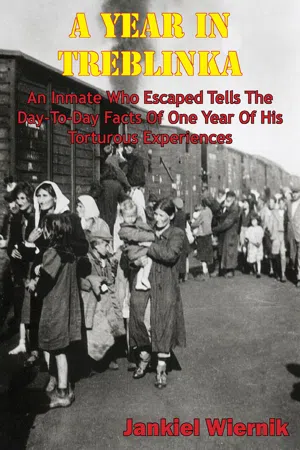

A Year In Treblinka

About this book

An Inmate Who Escaped Tells The Day-To-Day Facts Of One Year Of His Torturous Experiences.

Jankiel Wiernik was a Jewish property manager in Warsaw when the Nazis invaded Poland and was forced into the ghetto in 1940. Despite surviving the horrors of the ghetto at the advanced age of 52, he was sent to a fate worse than death at the notorious death camp at Treblinka, which he immortalized in his memoirs.

"On his arrival at Treblinka aboard the Holocaust train from Warsaw, Wiernik was selected to work rather than be immediately killed. Wiernik's first job with the Sonderkommando required him to drag corpses from the gas chambers to mass graves. Wienik was traumatized by his experiences. He later wrote in his book: "It often happened that an arm or a leg fell off when we tied straps around them in order to drag the bodies away." He remembered the horrors of the enormous pyres, where "10,000 to 12,000 corpses were cremated at one time." He wrote: "The bodies of women were used for kindling" while Germans "toasted the scene with brandy and with the choicest liqueurs, ate, caroused and had a great time warming themselves by the fire." Wiernik described small children awaiting so long in the cold for their turn in the gas chambers that "their feet froze and stuck to the icy ground" and noted one guard who would "frequently snatch a child from the woman's arms and either tear the child in half or grab it by the legs, smash its head against a wall and throw the body away." At other times "children were snatched from their mothers' arms and tossed into the flames alive."

"Wiernik escaped Treblinka during the revolt of the prisoners on "a sizzling hot day" of August 2, 1943. A shot fired into the air signalled that the revolt was on. Wiernik wrote that he "grabbed some guns" and, after spotting an opportunity to make a break for the woods, an axe..."

Jankiel Wiernik was a Jewish property manager in Warsaw when the Nazis invaded Poland and was forced into the ghetto in 1940. Despite surviving the horrors of the ghetto at the advanced age of 52, he was sent to a fate worse than death at the notorious death camp at Treblinka, which he immortalized in his memoirs.

"On his arrival at Treblinka aboard the Holocaust train from Warsaw, Wiernik was selected to work rather than be immediately killed. Wiernik's first job with the Sonderkommando required him to drag corpses from the gas chambers to mass graves. Wienik was traumatized by his experiences. He later wrote in his book: "It often happened that an arm or a leg fell off when we tied straps around them in order to drag the bodies away." He remembered the horrors of the enormous pyres, where "10,000 to 12,000 corpses were cremated at one time." He wrote: "The bodies of women were used for kindling" while Germans "toasted the scene with brandy and with the choicest liqueurs, ate, caroused and had a great time warming themselves by the fire." Wiernik described small children awaiting so long in the cold for their turn in the gas chambers that "their feet froze and stuck to the icy ground" and noted one guard who would "frequently snatch a child from the woman's arms and either tear the child in half or grab it by the legs, smash its head against a wall and throw the body away." At other times "children were snatched from their mothers' arms and tossed into the flames alive."

"Wiernik escaped Treblinka during the revolt of the prisoners on "a sizzling hot day" of August 2, 1943. A shot fired into the air signalled that the revolt was on. Wiernik wrote that he "grabbed some guns" and, after spotting an opportunity to make a break for the woods, an axe..."

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

Dear Reader:

For your sake alone I continue to hang on to my miserable life, though it has lost all attraction for me. How can I breathe freely and enjoy all that which nature has created?

Time and again I wake up in the middle of the night moaning pitifully. Ghastly nightmares break up the sleep I so badly need. I see thousands of skeletons extending their bony arms towards me, as if begging for mercy and life, but I, drenched with sweat, feel incapable of giving any help. And then I jump up, rub my eyes and actually rejoice over it all being but a dream. My life is embittered, Phantoms of death haunt me, specters of children, little children, nothing but children.

I sacrificed all those nearest and dearest to me. I myself took them to the place of execution. I built their death-chambers for them.

Today I am a homeless old man without a roof over my head, without a family, without any next of kin. I talk to myself. I answer my own questions. I am a nomad. It is with a sense of fear that I pass through human settlements. I have a feeling that all my experiences have become imprinted on my face. Whenever I look at my reflection in a stream or pool of water; awe and surprise twist my face into an ugly grimace. Do I look like a human being? No, decidedly not. Disheveled, untidy; run-down. It seems as if I was carrying a load of several centuries on my shoulders. The load is wearisome, very wearisome, but I must carry it for the time being. I want to and must carry it. I, who saw the doom of three generations, must keep on living for the sake of the future. The world must be told of the infamy of those barbarians, so that centuries and generations to come can execrate them. And, it is I who shall cause it to happen. No imagination, no matter how daring, could possibly conceive of anything like that which I have seen and lived through. Nor could any pen, no matter how facile, describe it properly. I intend to present everything accurately so that the entire world may know what “western culture” was like. I suffered while leading millions of human beings to their doom, so that many millions of human beings might know all about it. That is what I am living for. That is my one aim in life. In peace and solitude, I am constructing my story and am presenting it with faithful accuracy. Peace and solitude are my trusted friends and nothing but the chirping of birds furnishes accompaniment to my meditations and labors. The dear birds. They still love me otherwise they would not chirp away so cheerfully and would not become used to me so easily. I love them as I do all of God’s creatures. Maybe the birds will restore my peace of mind. Perhaps I shall someday know how to laugh again.

Perhaps that will come to pass once I have accomplished my work and after the fetters now binding us have fallen away.

CHAPTER 2

It happened in Warsaw on August 23, 1942, at the time of the blockade. I had been visiting my neighbors and never returned to my own home again. We heard the noise of rifle fire from every direction, but had no inkling of the bitter reality. Our terror was intensified by the entry of German “squad leaders” (Schaarführer) and of Ukrainian “militiaman” (Wachmänner) who yelled loudly and threateningly: “All outside”.

In the street a “squad leader” arranged the people in ranks, without any distinction as to age or sex, performing his task with glee, a satisfied smile on his face. Agile and quick of movement, he was here, there and everywhere. He looked us over appraisingly, his eyes glancing up and down the ranks. With a sadistic smile he contemplated the great accomplishment of his mighty country which, at one stroke, could chop off the head of the loathsome hydra.

He was the vilest of them all. Human life meant nothing to him, and to inflict death and untold torture was a supreme delight. Because of his “heroic deeds,” he subsequently became “deputy squad commander” (Unterscharführer). His name was Franz. He had a dog named Barry, about which I shall speak later.

I was standing on line directly opposite my house on Wolynska Street. From there we were taken to Zamenhof Street. The Ukrainians divided our possessions among themselves under our very eyes. They quarreled, opened up all bundles and assorted their contents.

Despite the large number of people, a deep quiet hung, like a pall over the crowd, which was seized with mute despair. Or, was it resignation? And still we were ignorant of the truth. They photographed us as if we were animals. Part of the crowd seemed pleased and I myself hoped to be able to return home, thinking that we were being put through some identification procedure.

At a word of command we got under way. And then, to our dismay, we came face to face with stark reality. There were railroad cars, empty railroad cars, waiting to receive us. It was a typical bright and hot summer day. What wrongs had our wives, children and mothers committed? Why all this? The beautiful, bright and radiant sun disappeared behind clouds as if loath to look down upon our suffering and humiliation.

Next came the command to entrain. As many as 80 personas were crowded into each car with no way to escape. I was dressed in my only pair of trousers, a shirt and a pair of low shoes. I had left a packed knapsack and a pair of high boots at home, which I had prepared because of rumors that we were to be taken to the Ukraine and put to work there. Our train was shunted from one track of the yard to another. In the meantime our Ukrainian guards were having a good time. Their shouts and merry laughter were clearly audible.

The air in the cars was becoming stiflingly hot and oppressive, and stark and hopeless despair descended on us like a pall. I saw all of my companions in misery, but my mind was still unable to grasp the immensity of our misfortune. I knew suffering, brutal treatment and hunger, but I still did not realize that the hangman’s merciless arm was threatening all of us, our children, our very existence.

Amidst untold torture, we finally reached Malkinia, where our train remained for the night. The Ukrainian guards came into our car and demanded our valuables. Everyone who had any surrendered them just to gain a little longer lease on life. Unfortunately, I had nothing of value because I had left my home unexpectedly and because I had been unemployed, gradually selling all the valuables I possessed to keep going.

In the morning our train got under way again. We saw a train passing by filled with disheveled, half-naked, starved people. They spoke to us, but we couldn’t understand what they were saying.

As the day was hot and sultry, we suffered greatly from thirst. Looking out of the window, I saw peasants peddling bottles of water at 100 zlotys a piece. I had but 10 zlotys on me in silver, with Marshal Pilsudski’s effigy on them, which I treasured as souvenirs. And so, I had to forego the water. Others, however, bought it and bread too, at the price of 500 zlotys for one kilogram of rye bread.

Until noon I suffered greatly from thirst. Then a German, who subsequently became the “Hauptsturmführer,” entered our car and picked out ten men to bring water for us all. At last I was able to quench my thirst to some extent. An order came to remove the dead bodies. If there were any, but there were none.

At 4 P.M. the train got under way again and, within a few minutes, we came into the Treblinka Camp. Only on arriving there did the horrible truth dawn on us. The camp yard was littered with corpses, some still in their clothes and some naked. Their faces distorted with fright and awe, black and swollen, the eyes wide open, with protruding tongues, skulls crushed, bodies mangled. And, blood everywhere, the blood of our children, of our brothers and sisters, our fathers and mothers.

Helpless, we felt intuitively that we would not escape our destiny and would also fall victims to our executioners. Bur, what could be done about it? If it were only a nightmare! But no, it was stark reality. We were faced with what was termed “eviction,” meaning eviction into the great beyond under untold tortures. We were ordered to detrain and leave whatever packages we had in the cars.

CHAPTER 3

They took us into the camp yard, which was flanked by barracks on either side. There were two large posters with big signs bearing instructions to surrender all gold, silver, diamonds, cash and other valuables under penalty of death. All the while Ukrainian guards stood on the roofs of the barracks, their machine guns at the ready.

The women and children were ordered to move to the left, and the men were told to line up at the right and squat on the ground. Some distance away from us a group of men was busy piling up our bundles, which they had taken from the trains. I managed to mingle with this group and began to work along with them. It was then that I received the first blow with a whip from a German whom we called Frankenstein. The women and children were ordered to undress, but I never found out what had become of the men. I never saw them again.

Late in the afternoon another train arrived from Miedzyrzec (Mezrich), but 80 per cent of its human cargo consisted of corpses. We had to carry them out of the train, under the whiplashes of the guards. At last we completed our gruesome chore. I asked one of my fellow workers what it meant. He merely replied that whoever you talk to today will not live to see tomorrow.

We waited in fear and suspense. After a while we were ordered to form a semi-circle. The Schaarführer (“squad leader”) Franz walked up to us, accompanied by his dog and a Ukrainian guard armed with a machine gun. We were about 500 persons. We stood in mute suspense. About 100 of us were picked from the group, lined up five abreast, marched away some distance and ordered to kneel. I was one of those picked out. All of a sudden there was a roar of machine guns and the air was rent with the moans and screams of the victims. I never saw any of these people again. Under a rain of blows from whips and rifle butts the rest of us were driven into the barracks, which were dark and had no floors. I sat down on the sandy ground and dropped off to sleep.

The next morning we were awakened by loud shouts to get up. We jumped up at once and went out into the yard amid the yells of our Ukrainian guards. The Schaarführer continued to beat us with whips and rifle butts at every step as we w...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- FOREWORD

- CHAPTER 1

- CHAPTER 2

- CHAPTER 3

- CHAPTER 4

- CHAPTER 5

- CHAPTER 6

- CHAPTER 7

- CHAPTER 8

- CHAPTER 9

- CHAPTER 10

- CHAPTER 11

- CHAPTER 12

- CHAPTER 13

- CHAPTER 14

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access A Year In Treblinka by Jankiel Wiernik in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Holocaust History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.