This is a test

- 144 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Temperance workers had their work cut out for them in the Upper Peninsula. It was a wild and woolly place where moonshiners, bootleggers and rumrunners thrived.

Al Capone and the Purple Gang came north to keep Canadian whiskey passing through Sault Ste. Marie to Chicago and Detroit. Federal enforcement agent John Fillion double-crossed both his office and the bootleggers. The Grand Hotel on Mackinac Island survived due to gambling and fine Canadian whiskey brought in by rumrunners, sometimes assisted by the Coast Guard. Author Russell M. Magnaghi dives into the raucous history of Yooper Prohibition.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Prohibition in the Upper Peninsula by Russell M. Magnaghi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

AWASH IN LIQUOR

The Upper Peninsula has a unique history from its earliest days in terms of the use of alcohol. The French who arrived in the mid-seventeenth century brought with them the fur trade, abetted by a trade in brandy. From their early arrival, the Jesuit missionaries saw the deadly effects of alcohol on the native population and railed against it. One of the first was Father Paul Le Jeune, SJ, who in 1632 at Quebec wrote of the destruction and depopulation of the Indians and noted that some Indians pleaded for an end to the trade in brandy. It was pointed out to the Jesuits that, once drunk, Indians “had an irrefutable excuse for whatever violence and destruction they committed.” In a spree, their villages became “veritable images of hell” with the drunken Indians burning cabins, tearing ears and noses from the face and killing their opponents. The captains and elders could not stop them, and those seeking safety fled into the woods. The missionary stayed with his home and church and waited until the furor ended. Brandy debauched the very people that the missionary was there to convert and civilize. Also, there was the concern for the safety of the French settlers when Indians went on an alcoholic spree.

The first real prohibitionist in the UP was the Jesuit Étienne Carheil, stationed at St. Ignace. He wrote an extensive report to the governor about conditions at Mission St. Ignace in late August 1702. First, he attacked the “infamous and baleful trade in brandy” that led to acts of brutality and violence, contempt and insult. He noted that if Louis XIV knew of these conditions, he would immediately forbid the trade. Second, he highlighted what amounted to prostitution with the soldiers keeping Indian women for their pleasure and monetary reward. Third, widespread gambling among the soldiers and fur traders set a terrible example and scandal for the Indians. Carheil wanted to see the total prohibition of brandy trade. This earnest Jesuit was despised and hated by the fur traders and by Fort Pontchartrain d’Étroit commander, and later Louisiana governor, Antoine Cadillac for his stance. However, the issue was never settled because officials were bribed and the hard economic reality of the times. If the French prohibited brandy to the Indians, they would trade with the English for rum and as the French traders told the Jesuits, “Do you want Catholic Indians drinking brandy or Protestant Indians drinking rum?”

Some Indians, horrified at the effects of alcohol consumed by their people, called for an end to the trade in brandy that they considered poison and “took away our senses and cause us untimely death.” Other Indians pointed out the physical destruction involved, the loss of finances to trade for useful goods and the destruction of family life. Time and again Indians pleaded with the French to prohibit the brandy trade. Many of the arguments by both the missionaries and Indians are similar to those of the twentieth-century prohibitionists.

The French and Indian War, which pitted the French and their Indian allies against the British, ended in 1761. The French lost and were removed from North America. Now the English had total control of the fur trade and Indian affairs. In May 1761, British captain Donald Campbell called for a prohibition of rum to the Indians because of its destructive effects on them. Soon after, General Jeffery Amherst called for the total prohibition of rum to the Indians throughout British North America because of “the many evils that daily arose from allowing it to be sold to the Indians.” Over the years, numerous incidents saw traders killed because they refused to trade rum to the Indians. Again we read stories of Indians in 1773 calling for a prohibition of rum because they saw more young men dying from rum than lost in warfare.

Nevertheless, outcast traders and vagabonds continued to introduce rum into the Great Lakes region. It was concluded that a police force would be needed to control the import of rum, which was impractical and costly. There was also the problem of Indians traveling, as they had in the French era, to Montreal and now to Albany and to obtain brandy or rum.

The British soldiers at Fort Michilimackinac had as their principal amusement drinking. Accounts tell of men and a trader who provided watered-down rum to the men and officers, who would have all-night parties consuming wine punch. A few of them became violent and belligerent and ended up breaking into residences, raping wives and severely beating the husbands when they tried to intervene. Fortunately, this activity involved a minority of individuals.

Rum continued to be important on the western border. In 1781, there were 3,084 gallons in storage at Fort Mackinac. Rum, rather than currency, was used to pay soldiers working on projects at the fort. At one point, this got costly for the British, and in 1815 at Drummond Island in the eastern UP, they decided to substitute cheaper porter or a good wholesome beer in place of rum. Despite all of the concerns for the effects of alcohol on the Indians and some would say on the British, liquor flowed into the Great Lakes much as it would during national Prohibition some 160 years later for all the same reasons.

Was liquor produced in the Upper Peninsula? We know that the recipe for spruce beer was introduced by the French. Not only did spruce beer have a “kick” to it, but its high vitamin C content prevented scurvy. Scurvy, commonly associated with long sea voyages, regularly broke out in the North Country, especially during the winter, when fruit and other sources of vitamin C were scarce. Spruce beer was relatively simple to make with local ingredients: spruce tips, maple sugar or molasses and water. The product was a low-grade beer, but most Frenchmen turned to readily available brandy. The British army, especially under General Amherst, promoted making spruce beer in the field, and it was readily available at Fort Mackinac. Alcoholic beverages were not that difficult to make locally, needing only fruit or potatoes, fermentation and then distillation. Little is written of this activity, as imported alcohol was readily available.

Prior to the War of 1812, a distillery—the first known in the Upper Peninsula—was opened on Mackinac Island. By the time of the war, it had been abandoned and was a place of refuge when the British invaded the island.

2

STRUGGLE FOR STATE

PROHIBITION

PROHIBITION

Throughout the nineteenth-century, alcohol abuse among the British and American soldiers stationed at Fort Mackinac was a major problem. The British army stationed there from 1812 to 1815 consisted of mostly illiterate enlisted men who could not gamble due to regulations and turned to alcohol. Liquor was a major problem for the U.S. Army stationed at the fort, and drunkenness was the major offense for being courtmartialed. There was little that military authorities could do with the civilian saloonkeepers. In 1889, they opened a beer bar in the fort with the idea of keeping the men away from the hard liquor in the village.

Despite congressional and executive regulations and orders, liquor continued to flow into the Great Lakes region, and the Indians were debauched and degraded by firewater. In 1832, some 8,776 gallons of liquor landed at Mackinac Island. Although John Jacob Astor, head of the American Fur Company (AFC), tried to convince the Indians that they would be more productive without liquor, they did not listen. The old story arose—if AFC did not provide liquor, there were British sources.

Mackinac Island was the entrepôt of the fur trade and a social center. With the return of traders, the celebrating included banquets and dances until dawn and plenty of rum. Drunkenness, brawling and frequent murders were part of life.

The effects of alcohol on the native population scandalized the Catholic and Protestant missionaries arriving in the early nineteenth century. Baptist missionary Abel Bingham settled at Sault Ste. Marie in October 1828. Liquor was plentiful, and intemperance was a common vice among the soldiers at Fort Brady, civilians and the Indians. As a result, he established the St. Mary’s Temperance Society in May 1830, and most officers and soldiers, as well as fur traders, became members. Even the fort sutler, John Hulbert, who had been selling twenty pints of whiskey a day, took the pledge and lost revenue.

In the summer of 1835, Dr. Chandler Gilman, a New York City physician on a vacation to Lake Superior’s Pictured Rocks, stopped at Sault Ste. Marie. He was appalled at the alcoholism among the Native American population—“slaves to rum,” as he described them.

The Methodist missionaries worked in the Upper Peninsula and fought intemperance. One of these was Reverend John Pitzel, who worked unceasingly to end the liquor trade and Indian consumption of alcohol. At the same time, in the 1840s and 1850s, the Catholic missionary Frederic Baraga promoted temperance and had Catholics take a pledge. The Mormon leader on Beaver Island, James Strang, protested against the destructive adulterated whiskey trade to the Indians by fishermen and traders from Mackinac Island.

In the mid-1840s, the central and western Upper Peninsula was open to settlement with the development of the copper and iron ranges. Thousands of people settled the region, and an early group of these settlers were immigrants who loved their beer. In the summer of 1850, the first German brewery opened at Sault Ste. Marie. German breweries quickly multiplied so that every major community had one. The demand for beer and whiskey was readily met in stores, hotel bars, main street saloons and scrub taverns located throughout the mining districts. The men did rough work under dangerous conditions and felt that, at the end of the week, they should celebrate at the local saloon. These saloons were the poor man’s equivalent to the social clubs to which wealthy Americans had access. The saloon was a social and fraternal headquarters where immigrants could feel at home. Mail could be delivered there, the latest local news spread and the salty food of the buffet encouraged beer to flow. Unions and fraternal organizations met in the saloon, which also developed political connections and provided tipplers with access to jobs. Every community, large and small, had its saloons, and many of them had breweries, as well. At the time, breweries could establish their own saloons or readily paid a prospective saloonkeeper to go into business, providing the entire bar equipment as long as the keeper served the financer’s beer.

German immigrant and brewer Charles Meeske included a lake and beer garden on his property. Courtesy of Superior View.

The newspaper accounts provide insights into what was being sold in the saloons. Martin Vierling, who arrived in Marquette in 1868, developed a well-known establishment and in 1912 had “a large stock of the choicest Wines and Liquors” and, in particular, “the best brandys.” He also had “ales and beers bottled, and in the wood.” Rothschild & Bending was a liquor wholesaler covering a large area of Michigan, providing “all the leading and most popular Kentucky whiskies which they see either in bond or the finest Champagnes, Ports, Sherries, Moselles, Burgundies, Sauternes and other wines, both imported or from our own superior vineyards; Dubois, Lizet & Co., Martelle & domestic Cognacs; the best makes of rums; De Kuyper & other well known gins…and a fine line of imported cordials and liquors.” One enterprising saloonkeeper in 1886 advertised in the Marquette Mining Journal that those who broke their temperance pledge were always welcome in his saloon.

In the center of the copper region, Calumet, with a population of 4,000 in 1877, had twenty-four saloons, or a saloon for every 166 residents. Similar figures can be tracked across the peninsula, with the iron-mining town of Republic’s 1,000 people serviced by eight saloons. The use of alcohol was extensive, and many people like Father Baraga and others dreaded the Fourth of July, a day when liquor flowed and drunkenness was rampant and accompanied by fights.

In the eastern UP at Sault Ste. Marie and Mackinac Island, tourists replaced the fur traders. Hotels and restaurants provided tourists on this northwestern border fine food and liquid refreshment. In 1860, two “gin cocktail makers” were mixing drinks in local saloons. Mackinac Island continued its reputation as a social center, catering to affluent summer resorters.

Bianchi’s Saloon (circa 1905) was a typical saloon serving as a social club for Italian immigrants. Courtesy of Marquette Regional History Center & R.M. Magnaghi.

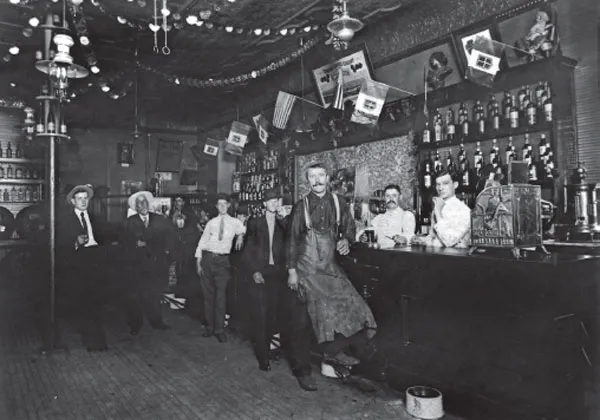

Early twentieth-century saloons like this one in Marquette served free lunches with salty foods to encourage beer drinking. Courtesy of Superior View.

De Paul’s Saloon in Sault Ste. Marie (1910) catered to soldiers from Fort Brady. Courtesy of Marquette Regional History Center & R.M. Magnaghi.

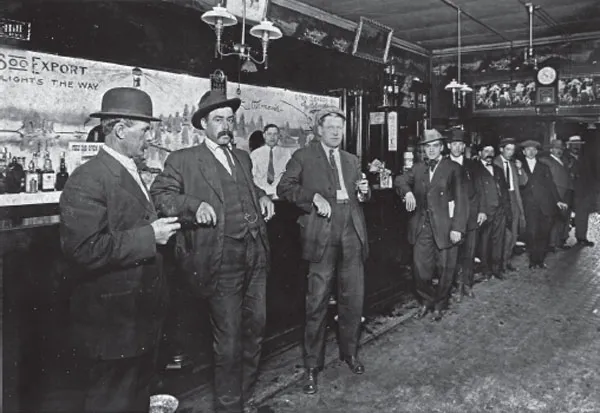

Such scenes ended with Prohibition. Courtesy of Superior View.

The consumption of alcohol grew with the population and troubled many people. There were various groups that first promoted the temperance pledge, but others looked toward total prohibition of liquor because of its abuse. In the late nineteenth century, Finnish immigrants developed a very strong temperance movement throughout the Upper Peninsula. The mining and timber companies were...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1. Awash in Liquor

- 2. Struggle for State Prohibition

- 3. Prohibition, a Reality: Or, How to Cope

- 4. Social Impact

- 5. End of Prohibition and Results

- 6. Touring Prohibition Sites

- 7. Cocktails on the Border

- Vocabulary of Prohibition

- Bibliography

- About the Author