- 110 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

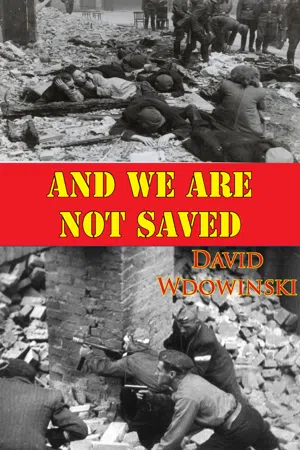

And We Are Not Saved

About this book

Succinctly and powerfully recounts the experiences of the author, a founding member of the Jewish Military Union, and important witness during the trial of Nazi criminal Adolf Eichmann. (EJ 2007) "Because the author was a leader of a major Jewish political party in Poland he is able to give us an understanding of the historical and social conditions that preceded the holocaust and gave it its impetus. Because he is a trained psychiatrist, we get illuminating insights into the behavior of the individuals and the masses, both heroic and inhumanly brutal, that determined the tragic destiny of the Jews throughout Europe."

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

THE GHETTO

CHAPTER III

The Ghetto counteracted the evil decrees of the Judenrat (as dictated by the Germans, of course) and executed with brutality by the Jewish police, by creating a relief society (ZYTOS) which was headed by former directors of the Polish Joint Distribution Committee and Zionist and non-Zionist political leaders. Later this organization became the nucleus for the political underground.

In every house a House Committee was established to gather information as to who was still in a position to contribute money, who had clothing to spare, who could share some food. One hundred forty one public kitchens were created where at nominal prices passable meals were served. Raw food, old clothes and linens were distributed amongst the poor. It was in the very best sense of the word a Self-Help organization which countermanded the conscienceless orders of the Jewish Council, some of whose officials did business with the Germans at the expense of the population in the Ghetto. Some of them grew richer, the population always poorer. The antagonism between the Judenrat and the ZYTOS was open and grew rapidly. During the “actions” the Jewish police revenged themselves by seizing the leaders of the Jewish Self-Help and handing them over to the Germans for deportation. One of the first such victims was Zagan, a left Poalezion, in spite of the fact that he had the best papers. He was a very fair and just person, and we always worked together in great harmony in the ZYTOS.

In the meantime, sad news began to seep through into Warsaw from the provinces, especially from those parts of Poland which were incorporated into the German Reich—Lodz, Poznan, Kalisz, Plock—truly Polish cities, which in the long course of history had always belonged to Poland, and were suddenly proclaimed German cities. They had to become Judenrein—free of Jews—as soon as possible. This was accomplished with German precision and organizational punctilio. Every German became master of life and death. Jews were beaten, tortured, shot. The so-called Volks-Deutsche—the local ethnic Germans in those cities—were willing helpers and contributors. They became rich overnight. The large Jewish textile mills in Lodz, for instance, were transferred to German hands without compensation. Jewish industrialists were compelled through abuse and beatings to clean up their mills, usually with their bare hands. Whoever could, fled to Warsaw or to some other city within the so-called General Government. In comparison with the areas incorporated into the German Reich, the territory in the General Government was considered a paradise.

The Jewish population in Warsaw grew. Refugees from the provinces who had relatives there, moved in with them. Others were forced to rent rooms, of course, from other Jews. The rooms were expensive and not easy to find. During the bombardment in September 1939 a quarter of the city was demolished and the Jewish section was particularly badly hit. In an area that had been previously inhabited by some 200,000 people, more than 400,000 were now herded together. Jews living in “Aryan” parts of the city were forced to move out and seek shelter in the Ghetto area. Apartments were at a premium. Even small apartments had to be shared by two or three families, single rooms occupied by five or six people, thus contributing to the decline in sanitary facilities.

In addition to the local Jewish population, Jews from small cities in the Warsaw district were also herded into the Ghetto, some 40 or 50 thousand of them, men, women and children.

Jews had no right to travel, so their guides, mostly Volksdeutsche, smuggled them through for handsome sums of money. On the way, they usually robbed them of their last penny and sometimes delivered them to the German authorities. And so they came from the provinces without money or clothing. The completely indigent were gathered upon their arrival in large centers. These were, for the most part, factory lofts bereft of every living accommodation. There the unfortunate Jews slept either on bare floors or on wooden planks. It took little time for these centers to become focal points of dangerous typhus and thyphoid epidemics.

Because of their hard and long journeys, which they had to make on foot in the middle of winter, and due to the lack of sanitary necessities (especially bathing) the refugees brought with them insects. Typhus broke out and spread like wildfire. There wasn’t a single home or apartment, even a room, which did not have at least one case of typhus fever. In 1941 alone, 43,000 people died in the Warsaw Ghetto of typhus fever and hunger. This was about 10 per cent of the population. An average of 100 or 200 burials took place daily. Soon it became impossible to give anyone a private burial. Often mass graves had to be dug. People collapsed in the streets from hunger. On the way from my apartment to the hospital, a distance of about one kilometer, I often saw in the course of one morning six, eight or ten corpses lying in the street. After a few weeks this became the normal appearance of the Jewish streets.

Folksongs sprang up dealing with hunger and epidemics. One of them had the following refrain: “I do not want to give up my bone” (from the French meaning food ration card). Actually it meant, I do not want to give up my life. In spite of all, one wanted to live. But wishing alone was not enough. All too often the “bone” was given up, especially by the poor, forsaken Jewish children.

In order to live, one had to smuggle. The official German food rations were too inadequate for life and barely missing death. The smuggling was carried on through the walls of the Ghetto. Hearses, which only an hour earlier unloaded typhus corpses, returned loaded with bread and rye flour. The Jewish cemetery bordered the Aryan section. Secret private mills were created in the Ghetto which ground the rye. In order to make this flour lighter in color and heavier in weight these secret millers added chalk and talc to the flour. This in turn caused mass colitis and gastroenteritis cases. There was no choice, one had to buy this flour because there was no other in the Ghetto. Officially, very little food came into the Ghetto. And even this little often went through the hands of conscienceless officials of the Judenrat, who made profit on the misery of their brothers. The possibilities to earn anything were practically nil. One was forced to sell his last possession in order to survive.

Water was not always available through the tap. We had to go to the well and pump water and bring it in. Washing, shaving became serious problems. We used the dirty water from washing with which to flush the toilets. Bath water had to be heated and two or three people used the same bath. A frequent bath was a luxury one could not consider. Added to the problem of obtaining water was the problem of fuel, wood or coal with which to heat it.

It is probably impossible for anyone who has not actually lived through this to imagine what daily life in the Ghetto was like. No matter what the hardships, we could never complain of boredom. The Germans were very ingenious with new laws and regulations which kept the population ignorant of the way to live within the law from day to day.

The Ghetto was established on November 16, 1940. The boundaries of the Ghetto were proclaimed and published in German and Yiddish all over the city, October 31st was set as the date when all the Jews who lived outside the Jewish section, about 150,000 of them, had to move into the prescribed area. The Jews had to leave all their possessions and enter the Ghetto without any property.

Before the establishment of the Ghetto, my wife and I lived in the non-Jewish part of Warsaw, where we also practiced as physicians. We were faced, like many others, with the problem of finding a suitable apartment which would also serve as an office. No sooner did we make arrangements for an apartment, than the boundaries were changed, the Ghetto area was made smaller, and we had to look elsewhere. This happened several times.

We were seven people including several relatives who lived with us because they fled from the provinces. Ordinarily we would be allowed to occupy only two rooms, but because we were physicians we obtained a third room. This made our situation an unusually good one. The few possessions that we took with us were carried on carts pulled by men. We accompanied these carts from afar not to be identified with them. On the way we were stopped by blackmailers who threatened to inform on us to the Germans, and we had to pay.

Other people were not as fortunate as we. They could find no rooms altogether. It was a common thing for strangers to walk into someone else’s apartment and sleep there with their clothes on.

Under such privations, the ordinary inhibitions of civilized human beings soon grew lax and were abandoned. When six or seven people had to share one room day in and day out, sexual intercourse in the presence of others was not unusual.

In due course of time food became such a problem that horse meat was considered good. When later on, after the first “action,” that became difficult to obtain, we used coagulated horses’ blood mixed with salt and pepper and spread it on bread to obtain some protein. In the morning there was no tea or coffee. One was nourished by hot potato soup with old bread, and it was a good day when one had even that.

Once the living quarters were settled in one way or another, it soon became clear that in order to survive one had to have hiding quarters as well.

There were unexpected raids by the Jewish police in apartment houses to round up people for labor camps, especially at the beginning of the “actions” to arrest those who did not have labor cards, and were therefore not productive members of the population (and for the most part those included the older citizens, for whom, if found, certain death was the verdict). The House Committees had a watch for such raids and the people were immediately notified to seek a hiding place. Where does one hide?

Necessity made us very ingenious, indeed. The Ghetto went into a furious activity of building bunkers—underground, between walls, behind closets, in attics—places where one could survive not only a couple of hours, but in some of them, the more elaborate hideouts, one could, if necessary, live for weeks. Some of the bunkers served as passageways to the Aryan side of Warsaw for purposes of smuggling food, contact with some friendly Poles, and a means of escape. Bunkers became arsenals for arms which were later used in the uprising and for headquarters for the various so-called commands. Whole blocks of houses were eventually connected by passages in cellars or in the foundation.

One need not go into the peril with which each such secret hiding place was constructed. Especially during the “actions” we were surrounded by Jewish police, Ukrainians and Lithuanians who were only too anxious to give the Germans a helping hand in any action against the Jews. Amongst the Jewish population there were some deluded individuals who, for the sake of personal immunity from arrest, a better labor card, or a bigger ration would gladly turn informers. Under such conditions we had to break down walls, construct new walls, bring in materials like planks of wood, cement etc. which were not too easy to camouflage, and do hammering without drawing attention to what was going on. Looking back upon it now, it seems incredible that we succeeded in constructing this complicated network of bunkers and underground passageways.

Some of the bunkers were found out and many Jews were slaughtered in them or dragged out to be sent on to Treblinka. But for the most part these bunkers turned out to be our only lifeline during the last stages of the Ghetto, and made it possible for us in the end to stand up against the Nazi war machine in the most dramatic revolt in modem history. It was in these bunkers as well as in other places that we learned to make Molotov cocktails and hand grenades. It was in these bunkers that we succored our wounded and gave direction to the fighters. And from these hideouts our youth jumped into the flames of Warsaw in the last days of the uprising.

The grotesque quality of our daily life in those days cannot be comprehended by the average person. Not only were we victims of hunger, disease, terror, human bestiality of every variety, but human foibles which in normal times might lead to mischief or a slight wrong easily rectified, was more often than not magnified into a situation that might mean death to the victim. Informers were one such hazard that we were all exposed to. Let me illustrate with a personal experience.

In December 1939 the hospital which was still in Czyste was very overcrowded with wounded from the bombardment and homeless people. Amongst them there were also a few cases of typhus fever. One day Dr. Schremf, an S.S. doctor who was the medical supervisor of the Jews, came to the hospital and asked how many typhoid cases there were. The Director, who had the records, gave him the number. Meanwhile, at the end of the long courtyard a new typhoid case was being wheeled in, which was not yet recorded by the office of the Director, so that now there was actually one case more than was quoted to the Nazi. For this discrepancy Dr. Schremf had the Director of the hospital and the bookkeeper arrested, because Jewish doctors lie. Because of his great concern for the health of the population, he declared a quarantine so that the doctors could not leave the hospital. So, I had to spend three weeks in the hospital.

My wife, who was home, came to see me one day and told me that a Dr. Epstein who lived near us had a relative in the hospital, a Mrs. K. Would I find her and look after her. After much trouble, because the hospital was terribly overcrowded, I finally found the woman, who was paralyzed, inarticulate and completely hopeless.

When the quarantine was over and I returned home, this woman’s daughter came to see me and thanked me for taking an interest in her mother. Since she was returning home (she lived in Czestochowa) she asked me to write to her occasionally and tell her how her mother was doing. She wanted to pay me for the visit, but I refused to accept any remuneration since it was a hospital case.

In the weeks that followed I was bombarded with letters from that family about the mother’s condition. In order to console them, I once mentioned some minor thing of improvement. This was in the winter of 1940. Within that time, on the order of Dr. Schremf, all hopeless cases were transferred to a special building, outside the hospital. This woman was amongst them.

One day in the summer of 1940, there was a great commotion in the hospital that Dr. Schremf was calling to see me. This could only be an ill omen.

Dr. Schremf faced me with a long typewritten accusation made by the family that I had neglected the patient Mrs. K. and that I had been paid 50 zloty as a fee for a patient in die hospital. I was immediately dismissed from my post and he told me that further steps against me were yet to be taken. This meant the Gestapo.

All complaints were always sent to the Judenrat, and so, of course, was this case. Meanwhile, I lived in the shadow of the Gestapo. I found out later that the daughter of the woman K. and her married sister had been present in the courtyard of the hospital while the Nazi doctor faced me with the charges. It turned out that the married sister had been an employee in my brother’s firm before the war and had been discharged for some reason. This was her opportunity for revenge.

During the weeks that followed Dr, Israel Milejkowski, Chairman of the Department of Public Health, one of the few decent and honest members of the Jewish Council, who was never overwhelmed by his position and power, on several occasions asked Dr. Schremf to rescind his order, but he would not hear of it. Finally, one day when Dr. Schremf was in a particularly good mood because he was leaving for vacation, Dr. Milejkowski again broached this subject, and this time Dr. Schremf agreed to let me go back to my post in the hospital and dropped the case. As far as the Nazi was concerned the matter was settled.

But not so with one of my Jewish colleagues. Dr. Milejkowski’s assistant, Dr. Wortman, a former Revisionist, insisted that the case had to go through the regular channels. A formal complaint was made against me to the Judenrat and the court had to try the case. The fact that in actuality the case was officially dropped by the Nazi chief who did not wait for any court action when he saw fit to punish a Jew, held no meaning for my Jewish colleague. So we went to court, and I was defended by the lawyer Grossfeld and was, of course, completely cleared. And so, the Judenrat had one more opportunity to utilize its great prestige and all the power vested in its musical tragi-comedy court.

Upon such deluded thinking, upon such human weaknesses and desire for vengeance, or for power, hung the fate of many a human being in the Ghetto.

Of all the gruesome scenes and sounds of the Ghetto that remained with me throughout these years, the saddest and most haunting of all are the ones concerning the children.

Children of the Ghetto—a cursed generation that played with corpses and death, that knew no laughter and no joy—children who were...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- ACKNOWLEDGMENT

- PREFACE

- IN THE BEGINNING…

- GERMAN OCCUPATION- PRE-GHETTO PERIOD

- THE GHETTO

- THE UPRISING

- THE HARVEST IS PAST

- A NOTE ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access And We Are Not Saved by David Wdowinski in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Holocaust History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.