![Last Flight From Saigon [Illustrated Edition]](https://img.perlego.com/book-covers/3020649/9781782898955_300_450.webp)

- 120 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Last Flight From Saigon [Illustrated Edition]

About this book

Illustrated with over 30 maps, diagrams and photos

The Southeast Asia Monograph Series is designed and dedicated to telling the story of USAF's participation in the Vietnam War. This monograph, the sixth in the Series, adds another exciting chapter to our continuing effort to bring forth and highlight the dedication, courage, and professionalism of the U.S. airman in combat. The primary intent of this series is to emphasize and dramatize the human aspects of this long and frustrating struggle, straying somewhat away from the cold hard statistics of "tons of bombs dropped" and "structures destroyed," etc., frequently the headliners in historical presentations.

"Last Flight From Saigon" is an exciting and moving account of how all our Services, as well as several civilian agencies, pulled together to pull-off the largest aerial evacuation in history-what many have referred to as a modern day Dunkirk. The three authors, intimately involved with the evacuation from beginning to end, have carefully pieced together an amazing story of courage, determination and American ingenuity. Above all, it's a story about saving lives; one that is seldom told in times of war. All too often, critics of armed conflict make their targets out to be something less than human, bent on death and destruction. One need only study the enormity of the effort and cost that went into the "evacuation of Saigon," and the resultant thousands of lives that were saved, to realize that the American fighting man is just as capable, and more eager, to save lives than he is in having to wage war.

The Southeast Asia Monograph Series is designed and dedicated to telling the story of USAF's participation in the Vietnam War. This monograph, the sixth in the Series, adds another exciting chapter to our continuing effort to bring forth and highlight the dedication, courage, and professionalism of the U.S. airman in combat. The primary intent of this series is to emphasize and dramatize the human aspects of this long and frustrating struggle, straying somewhat away from the cold hard statistics of "tons of bombs dropped" and "structures destroyed," etc., frequently the headliners in historical presentations.

"Last Flight From Saigon" is an exciting and moving account of how all our Services, as well as several civilian agencies, pulled together to pull-off the largest aerial evacuation in history-what many have referred to as a modern day Dunkirk. The three authors, intimately involved with the evacuation from beginning to end, have carefully pieced together an amazing story of courage, determination and American ingenuity. Above all, it's a story about saving lives; one that is seldom told in times of war. All too often, critics of armed conflict make their targets out to be something less than human, bent on death and destruction. One need only study the enormity of the effort and cost that went into the "evacuation of Saigon," and the resultant thousands of lives that were saved, to realize that the American fighting man is just as capable, and more eager, to save lives than he is in having to wage war.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER I. HANDWRITING ON THE WALL: POLITICS ECONOMICS, LOGISTICS, 1973-1974

On 28 January 1973, the Paris Ceasefire Agreement for ending the war in Vietnam was signed. That date is chosen as the starting point for the drama of FREQUENT WIND, which culminated early on the morning of 30 April 1975.

Looking back at the US involvement in the Vietnam War, one could give many reasons why it ended as it did, and most reasons probably contributed in one way or another. One of the key decisions which affected the outcome was the pronouncement of the Nixon Doctrine on Guam in July 1969. In his statement of US Foreign Policy for the 1970s, President Nixon outlined the guidelines of partnership, strength, and willingness to negotiate. His central thesis was that the US would participate in the defense and development of friends and allies, but that:

“America cannot and will not . . . conceive all plans . . .design all programs. . .execute all the decisions. . .and undertake all the defense of the free nations of the world. We will help where it makes a real difference and is considered in our interest”.

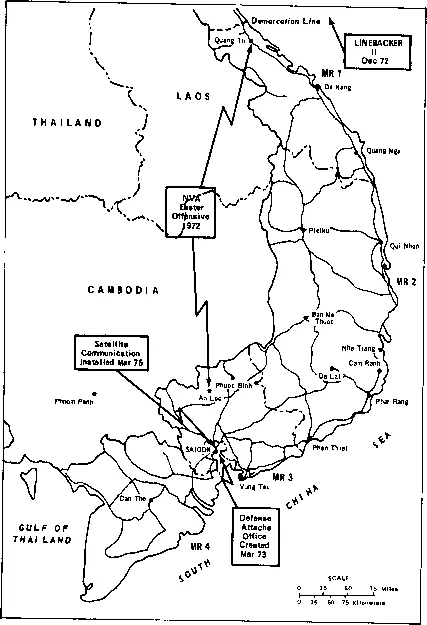

By the spring of 1972, most American ground forces had departed South Vietnam. This was in compliance with President Nixon’s plan of Vietnamization, whereby the Vietnamese would eventually take over all the fighting to preserve their own country. The threat of American air power held the shaky Vietnamization program together, buying time for the South Vietnamese to build their strength. The North Vietnamese Easter Offensive of 1972 was beaten back, largely through the massive use of US aerial firepower—including both Operation Linebacker I, the heavy bombing of North Vietnamese supply routes, and the direct air support of the South Vietnamese Army. Ceasefire negotiations between Dr. Henry Kissinger and the North Vietnamese seemed to be making progress in the fall of 1972, only to bog down however, in mid-December.

Operation Linebacker II, the massive aerial attack on the North Vietnamese heartland, helped convince the North Vietnamese that the US would continue to support the Thieu regime in the Republic of Vietnam, and may well have forced the North Vietnamese back to ceasefire negotiations in January 1973. The result was what the US, on 28 January 1973, called "peace with honor” for America, the starting point for this story.

Figure 1. South Vietnam, April 1975.

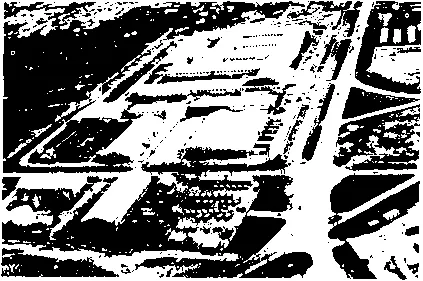

In this era of “peace" was born the Defense Attaché Office, Vietnam (figure 2). Conceived in October 1972, the Defense Attaché Office (DAO) was located in the old Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) headquarters building on Tan Son Nhut Airport, on the north edge of Saigon—about a 15 minute auto trip from downtown Saigon. The US Joint Chiefs of Staff provided preliminary guidance for the creation of the DAO and instructed MACV to establish in coordination with the American Embassy, a Defense Attaché Office of not more than 50 military spaces to be fully operational on an anticipated ceasefire date plus 60 days, and to arrange for necessary in-country management, of continued resupply, local maintenance, and contractor support for Republic of Vietnam Armed Forces.

Forty days after the activation of the DAO the JCS approved the final manning tables providing for 50 military and 1,200 US civilian spaces. With an added authorization of 3,500 Vietnamese spaces, the DAO became an organization of 4,750 individuals. On 29 March 1973, with the inactivation of MACV, the US officially ended its military combat role in Vietnam. A total of 209 military personnel remained in South Vietnam (50 officers from all services at the Defense Attaché Office and 159 Marine guards assigned to the Saigon Embassy and the four Consul General offices at Da Nang, Nha Trang, Bien Hoa, and Can Tho). The Marines provided, security services in the four Military Regions of the country. From its origin , the DAO was in a continual process of reducing manning. Contractor personnel were being cut at an even greater rate than US government employees. By the end of 1974, reductions-in-force lowered the total DAO strength to 3,900 employees (50 military officers, 850 US civilians, and 3,000 Vietnamese).

Figure 2. Defense Attaché Office, Tan Sort Nhut AB, Saigon (Formerly MACV Headquarters).

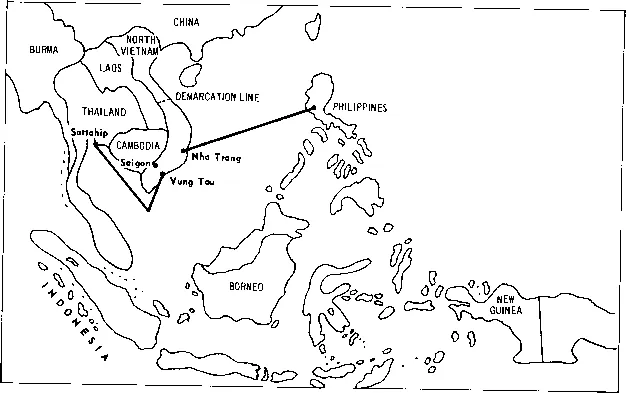

Figure 3. Underwater Communications Cables.

From the outset, the command structure of the Defense Attaché Office was unique, primarily because of its active role of monitoring South Vietnamese military activities. The first Defense Attaché for the new DAO was Major General John E. Murray, USA, who moved from his former job as Director of MACV Logistics to the position of Attaché. He was the ranking American military officer in Vietnam.

General Murray had two bosses. One was the American Ambassador, Graham A. Martin, who had taken office in July 1973. Ambassador Martin directed all in-country political, economic, and psychosocial aspects of the American mission. On the military side, General Murray worked for the Commander, US Support Activities Group-7th Air Force at Nakhon Phanon (NKP), Thailand. Later, he reported directly to the Commander-in-Chief, Pacific (CINCPAC) in Hawaii. Doubtless, this arrangement violated the principle of “unity of command.”

The Attaché published Quarterly Assessments{1} describing the situation in Vietnam. In his first Assessment, dated 30 June 1973, General Murray pointed out some changes created by the departure of US Advisors upon whom the Vietnamese had relied. After claiming that the Attaché could not submit a more objective report because his staff was not as personally involved in the subject as had been the advisors, he went on to say that the source data coming from the Vietnamese might not be completely reliable because it could no longer be validated through the advisor system. He added that Vietnamese staff personnel were often startled by US interest in military details and expressed chagrin at Vietnamese lack of concern. He complained about the South Vietnamese lack of a sense of urgency, inaccurate reporting, and inability to see the need for timely actions and responses.

On 30 September 1973, General Murray updated his previous report with a stern warning of an enemy logistical buildup which lacked only the requisite manpower to make it a serious threat of a major, country-wide offensive. At the same time, he lamented the incompleteness of the “Vietnamization Program.” He was especially disturbed about the Vietnamese Air Force. Training was incomplete, operational readiness was not satisfactory, the airlift record was disappointing, and most of the bombing was being done from altitudes of 10,000 feet and higher—not only reducing accuracy but also causing interservice bitterness.

General Murray continued as Defense Attaché until the summer of 1974, never changing the general tone of his quarterly reports. The enemy buildup continued, Vietnamization lagged in several vital areas, and the economy that supported the South Vietnamese Government, though more resilient than might have been expected, was nevertheless stricken with a bad case of inflation. He closed his tour with a pessimistic report maintaining that the contest could be won but only with the strong materiel support from the US Congress and taxpayers.

In August of 1974, Major General Homer D. Smith, USA, replaced General Murray. He, too, was a logistician, as materiel deficiencies were deemed to be one of the weakest areas of the South Vietnamese Armed Forces. From the outset, General Smith was plagued with the same problems faced by his predecessor, and his reports were not much different from those cited earlier. The requirements for the fiscal year just begun had been established as $1.4 billion. The appropriation, when it finally emerged in September 1974, had been cut down to half that figure. Smith was soon reporting that some of the earlier pessimistic predictions of the effects of reduced funding were now coming true. He complained that though the spirit of the South Vietnamese remained high (all things considered) the want of money had deprived them of most of their offensive capability. Thus, the initiative had been thrust into the hands of the North Vietnamese, and the outlook was grim indeed unless new material aid was soon forthcoming. By the end of the year, the Communists were beginning to take advantage of the weaknesses Smith cited by probing around Phouc Binh—the beginning of the last battle.

If the full weight of American economic power could not be deployed to stem the onslaught, could military power be used? Many thought that the Ceasefire of January 1973 carried at least an implied commitment to reintroduce US airpower to the fighting if the Communists violated their agreement.

There were some remnants of American airpower in Southeast Asia: the B-52s and their tankers were still at U Tapao, and F-4s, A-7s, AC-130s and F-111 As were poised at the other Thai bases— though a decision had already been made to remove them during Fiscal Year 1976.

Fortunately, the South Vietnamese did not know of that decision. Rather, the mere presence of American airpower, close by in Thailand, gave them hope. Regardless of where the authors travelled in-country or to whom they talked, military or civilian, the typical questions usually came out: “When will the Americans return with their airplanes to stop the Viet Cong (VC) and the North Vietnamese Army? When will the B-52s come back?” It wasn’t a question of “will they return?” it was “when?” Most Vietnamese talked to thought that the US would help them when they needed it. It was a difficult task to sidestep such questions since the possibility of a resumption of American bombing was slim, if not non-existent.

In addition to the overwhelming confidence of the South Vietnamese that the US would return, they were fully convinced that Saigon was invincible. If all else failed, one could make it to the “Jerusalem” of South Vietnam and be safe. This was a false but consistent illusion.

The factors noted above plus many more led Americans serving in South Vietnam in December 1974 to think the unthinkable—a mass evacuation of Americans from Vietnam was becoming a very real possibility. To most of the American military in Saigon, evacuation was a foregone conclusion. It was not a matter of “if,” it was a matter of “when.” Clearly 1975 looked like a bad year!

Plans and Preparations for the Inevitable

In any venture, especially in a strange environment, common prudence dictates that one at least give some general thought to possible actions if the worst should occur. By the beginning of 1975, the warning signals were loud and clear. Though few thought the collapse would be so sudden, most were sure that it would come in the not-too-distant future. Thus, there was renewed interest in planning for the worst. How were we to remove a considerable number of Americans and Third Country Nationals from danger? How many South Vietnamese lives were in jeopardy? What could we do to bring them to safety? Of course, a plan to achieve these things was prepared quite some time before the final crisis. Although the evacuation did not much resemble the original plan, it is nevertheless necessary to discuss briefly the planning process to give the reader a better grasp of the background to the crisis.

As the hurried evacuation of the American Embassy in Poland before Hitler’s 1939 onslaught showed, the maintenance of an evacuation plan has many precedents and has by now become a standard operating procedure. The work done on TALON VISE (original code name of the evacuation plan, later changed to FREQUENT WIND) during 1974 and 1975 was not so much planning as it was updating an existing plan in a rapidly changing situation. TALON VISE-FREQUENT WIND was a military contingency plan (USSAG/7AF) developed at the request of the U.S. Ambassador for the evacuation of personnel from the Republic of Vietnam. Many other factors, however, complicated the Ambassador’s work on the plan. For some time force levels had been changing in Southeast Asia and all over the Western Pacific, and this called for changes in the evacuation arrangements. It was difficult to determine the exact numbers to be evacuated. By the beginning of 1975, the planners had a fairly stable figure of 8,000 Americans and Third Country Nationals, but there never was a firm figure for the number of Vietnamese to be carried out. Estimates varied from 1,500 to 1,000,000 Vietnamese who had been so closely associated with the US that their lives would be endangered under a Communist regime. An extremely unstable personnel situation had been the rule among the allied forces for a long time and seemed certain to continue. To further complicate the situation, there was no reliable ground system of communications for alerting and gathering up individuals for evacuation. Only the radio offered any hope of achieving that part of the job. In the end, then, not only was the task monumental, but it was nearly impossible to even define it.

What resources were available for accomplishing the job? Because of its speed, flexibility, and relative security, airlift was thought to be the most desirable mode of evacuation. Movement on the ground was feasible in only a very few areas of Vietnam. Sealift was practical, but the line of communications down the Saigon River to the sea was vulnerable to interdiction from the banks of the stream. The problem with airlift was that the main terminal, Tan Son Nhut airport, was in the midst of the congested area of the capital, and no one could foresee what the attitude of the local population would be during the final withdrawal, It was known that enemy SA-7{2} missiles were available in the region and that fixed-wing aircraft operating in and out of Tan Son Nhut would be highly vulnerable to such weapons. Moreover, USAF airlift planes and personnel had long since been withdrawn from South Vietnam, and the only reliable airlift available in the country was Air America. The helicopters and smaller aircraft of this company were invaluable for removing people from remote locations, but they did not have the capacity or the range to carry the evacuees away from Vietnam. Of course, the Military Airlift Command could schedule its own C-141s and C-5s as well as the airliners of the contract carriers into Tan Son Nhut for the rescue. Some of these aircraft were available on very short order from places in the Western Pacific, and others could be brought in from the United States with remarkably little delay. Then too, there was a considerable fleet of C-130s stationed in the Philippines only 1,000 miles away from the scene. Thus, assuming that the terminal at Tan Son Nhut would be secure, a sizable number of airlift aircraft could be made available for the task.

However, if the security of the airfield degenerated to the point where large, fixed-wing aircraft could no longer safely land and take off, another option was still available—helicopters. Some Air America helicopters could be used, but many more were available on the Navy’s carriers and could be flown to and from Saigon by their Marine pilots.

What resources were available for establishing and maintaining the security of the evacuation? USAF bases in Thailand, only a few hundred miles away, still had about 30,000 people. These bases could supply daytime close air support with their A-7s, F-4s, F-111s, and OV-l0s. All through the night, even during adverse weather, the Thailand-based AC-130s could cover the withdrawal with their 105 mm cannon and electronic sensing devices. ...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- FOREWORD

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- PREFACE

- CHAPTER I. HANDWRITING ON THE WALL: POLITICS ECONOMICS, LOGISTICS, 1973-1974

- CHAPTER II. AN AGONIZING THREE MONTHS: DETERIORATION, JANUARY THROUGH MARCH 1973

- CHAPTER III. HISTORY’S LARGEST AERIAL EVACUATION: INITIAL EFFORTS IN SAIGON 1-4 APRIL 1975

- CHAPTER IV. THE QUICKENING PACE: FIXED WING EVACUATION BUILDUP, 5-19 APRIL 1975

- CHAPTER V. THE FLOOD TIDE: THE MASSIVE FIXED-WING AIRLIFT 20-28 APRIL.

- CHAPTER VI. THE LAST FLIGHTS FROM SAIGON: FREQUENT WIND’S HELICOPTER PHASE, 29-30 APRIL

- CHAPTER VII. THE FINAL DRAMA: SEALIFT AND INDIVIDUAL FLIGHT. 29-30 APRIL 1975

- CHAPTER VIII. THE MORNING AFTER: A FINAL TALLY

- EPILOGUE

- APPENDIX I: AUTHORS

- EDITOR

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Last Flight From Saigon [Illustrated Edition] by Lt.-Col. A. J. C. Lavalle in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.