![]()

CHAPTER I — MY YEARS IN THE ARMY

I FIRST saw the light among the wonderful Finger Lakes of central New York, in the historic region made famous by Red Jacket and other noted chiefs of the Iroquois confederacy. If the legend be true, these lakes were formed when the Great Spirit dropped here a slice of the happy hunting grounds and left the imprint of his fingers in the soft rocks so that his chosen people, the Iroquois, could ply their bark canoes in deep waters and build their habitations on the shores of secluded lakes.

Along Seneca Lake and the deep woods that bordered it I passed many a happy day of my boyhood, encroaching, no doubt, upon many hours that should have been devoted to school. The inclination I had for forest life and scenes, and later for the free life of the plains and mountains of the Far West, may have been derived from ancestry, for my family claims descent from that strong character of early New England days, Hannah Dustin, who, having been captured by Indians, rose stealthily in the night when all were asleep, and killing several of her captors, finally reached her home and friends after an exhausting journey through swamps and forests.

The opening steps in the Civil War, culminating in the attack on Fort Sumter in April, 1861, came with a series of shocks to my native village of Geneva, and the excitement that prevailed is still fresh in my memory. There was marching by night of “Little Giants” and “Lincoln Clubs” in resolute and solemn array, and I yet recall how the oil dripped down from dusky, smoky torches onto black wide-awakes and capes. Many of those who so gaily or solemnly passed marched later in lines of battle, and came back from the war battered or crippled, or came not at all.

Nearly everybody wore a rosette of red, white, and blue, and some of these were very gorgeous indeed. A regiment of volunteers was soon recruited and a training camp was established in the outskirts of the village. I well remember the day when the regiment, fully equipped for service, marched down Main Street before my entranced eyes to the music of a line of drummer boys stepping in front, among whom, to my astonishment, I saw two or three of my schoolfellows. This set me to thinking deeply and I deplored the fact that my youth and my position as eldest in the family rendered it imperative that I remain with my mother, sister, and brothers.

Toward the close of the war, having obtained my mother’s consent, I left the academy at Lima, New York, where I had been attending school, to enlist as a soldier. I was then not yet sixteen years of age. I have a dim recollection of going before a board of officials in my native village, who, after an examination, directed me to proceed to Rochester, where I would have the opportunity I desired to join the army.

On reaching Rochester I presented myself to the recruiting officer for the Fourth New York Cavalry, but was summarily rejected because of my youth. Made wise by this first failure—although at that period I had not heard of the young recruit who, having been rejected in his first effort to enlist, rushed over to a shoe store, had himself fitted to a pair of shoes, and ordered that they be marked number eighteen, so that he could say he was over eighteen—I succeeded in my second attempt. The regular army officer who examined me on this occasion seemed impressed by my good looks and tall stature. I was enrolled in the regular establishment, and shortly a sergeant took me in charge and furnished me a suit of army blue, which I donned with much satisfaction. So green was I at this time that I did not know the difference between the volunteer and the regular army.

Passing over trivial incidents, such as being served with coffee without milk and bread without butter, I soon found myself en route for New York. For a few days we were housed with other recruits in a curious, circular structure called Castle William, which stood on the point of Governors Island nearest the Battery, when we were ordered aboard a transport bound for City Point, Virginia. I have little recollection of our voyage except that it was a misty and boisterous one. Coffee, hard-tack, and meat were served out to us on the forward, unprotected deck of the ship, and I did not see an officer until we arrived at City Point.

Here, all was confusion. A multitude of tugs and steamers enlivened the water-side, while officers and soldiers rushed about on shore amid a lot of military wagons, tents, and other equipment. Disembarking, we were marched a short distance to a camp and there lined up for assignment to certain skeleton companies, whose ranks had been depleted by losses suffered in recent service. We were then issued equipment and dismissed.

My captain proved to be a stout, cocky fellow who had evidently been promoted from the ranks. He was, however, an efficient officer. “Bring down those hands with vim,” was a favorite order when on drill. For some time our service consisted in guarding prisoners of war, and also general prisoners in bull pens.

After the cessation of hostilities, we marched from Burkesville to Richmond, the view of which was marred by burned buildings and bridges. Later we took the road to Washington. At no time had I met more than one battalion of my regiment. Our battalion was commanded by Captain Robert Hall, and Lieutenant Theodore Schwan was adjutant. When next I met these officers, a third of a century later, one was in the adjutant general’s office in Washington, and the other was in the Philippines, and both were brigadier generals.

Arrived in Washington, the battalion encamped south of the Potomac in the pines, where we remained until after the Grand Review. On the evening of June 6, 1865, I was detailed as one of fifty men to act as guard on the following day near the reviewing officer, on the occasion of the review of the Sixth Army Corps. Long before daybreak we were on the road marching through the misty, fog-covered stretches to the Potomac. On either side, as we passed, could be heard the morning call of bugle, fife, and drum, and stentorian voices giving commands to moving cavalry.

Finally, in the morning light we saw the Potomac and the low land about it. We crossed the historic Long Bridge, and at length stopped to rest at some point on Pennsylvania Avenue. Here, I remember, I purchased a small pie of a negress, who had a stand near by. The pie looked fine, but when tested it proved to be thin and tough. The crust was not of the kind that melts in the mouth, and I retired disappointed and hungry; the soiled shin-plaster which I paid for it was wasted.

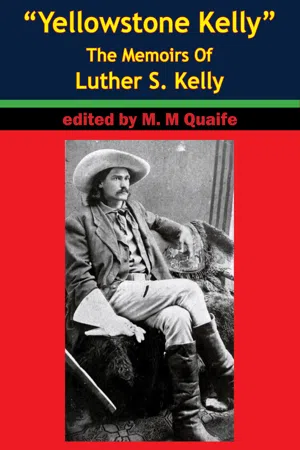

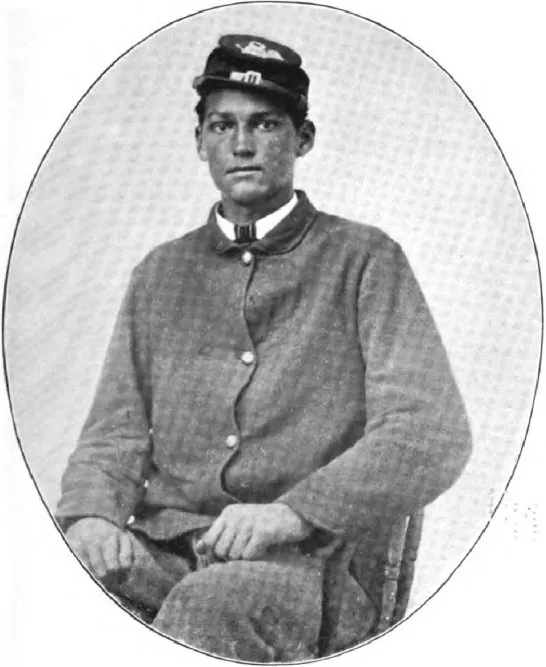

LUTHER S. KELLY

As a Private, Company G, 10th Infantry, April, 1865.

From a Daguerreotype.

About ten o’clock the officer in command lined us up in front of the reviewing stand. As yet no one was at hand to occupy the vast structure, which rose tier upon tier of rough boarding, gaily decorated with flags and bunting, although crowds of holiday sightseers were beginning to throng the streets. We were soon ordered to stand at ease, and it was a relief to look about and compare notes.

Presently squads of police came along and stationed men at intervals to clear the way. Our detachment was brought to attention, for the column could be seen in the distance moving down the avenue. By this time the reviewing stand was filling rapidly through the different entrances; generals and staff and field officers were much in evidence, while members of Congress and others prominent in official and civil life were being frequently greeted with bursts of cheers.

Soon all was excitement, as a burst of music heralded the approach of a column of mounted police who led the way, followed, as I recall, by an escort of cavalry. Close on their heels came the commander of the Sixth Corps and his staff, followed by orderlies, the corps headquarters guards, and bands; then came the first division with its staff, followed by columns of troops passing in review in lines of companies, the left of the line being only a few yards away from where we were. As the heads of the different organizations passed along we stood at “present arms” until our fingers and arms ached with the tension. Bronze-bearded fellows they were, clad in the blue field uniform of blouse and cap or black hat; infantry, cavalry, and artillery marched with the precision and compelling force of veterans—a latent power that enemies of the Republic might well have taken note of.

I was but a recruit, and was unable to identify any of the famous warriors who moved so gallantly by, but I noted one dashing officer of high rank whose horse seemed to have gotten the bit and was bearing his rider at full speed along the line of march before he could curb him. It may have been Custer of the waving locks, although I am not sure.

All day long that column passed, and our arms became numb with saluting and holding our rifles at a carry. Some regiments were arrayed in white collars and many had new uniforms; other regiments, perhaps direct from the field, had had no time to make requisitions on the quartermaster for new clothing. So they passed, horse, foot, and artillery, followed by camp followers and “bummers” in strange and quaint attire gathered in foraging forays on the flanks of armies.

After our battalion had been encamped for some time at Kalorama Heights my company was sent into Washington and stationed in some old quarters, where we suffered a good deal of discomfort from the heat and the unsavory conditions generally. At length word came that our regiment was to move to the Northwest to take station on the frontier. Presently, after considerable preparation, we boarded some antiquated day-coaches and began our journey. Of it I remember little save an incident at one station where iron kettles of hot coffee, sweetened with molasses, were brought into the car and with this, together with hard-tack and slices of pork, our hunger was satisfied.

Arrived at St. Paul, my company and one other were assigned to Fort Ripley on the upper reaches of the Mississippi River, and shortly after we took up the line of march through a thinly settled region to that point. There was little excitement at this post and when winter set in the routine of duty was dreary enough, but in the spring, when the genial sun transformed the dead verdure into a blanket of green, I joyed in taking my rifle and rambling through the silent forests and along the pebbly banks of the Mississippi and its tributary streams.

When spring had advanced somewhat, the company received orders to march across country and take station at Fort Wadsworth, Dakota Territory, in the vicinity of Big Stone Lake. The country was still but sparsely settled and in our march we encountered but few towns or villages, so that it was not uncommon to see deer break away from the head of the column. Whenever this occurred the captain would direct two of our best shots, who were usually veteran soldiers, to go ahead and kill them. I noticed, however, that they seldom brought in any meat. We came upon numerous lakes, and our camp was usually pitched on the bank of one of them. Here I was in my element, for I was an expert swimmer, and I rather astonished the officers and men by my long underwater dashes.

Finally, my chance came. We made an early camp, and after the tents were pitched I walked to the captain’s tent, saluted, and asked permission to go hunting.

“Have you had any experience in hunting?” he inquired.

“No, sir,” I replied, “but I do not see any of the expert hunters bringing in game, and I would like to try my hand.”

He smiled, and gave me the required permission, warning me at the same time not to get lost.

I had noted, a mile back on the road as we came along, an open glade crossing a water course. I reached this opening through the woods and skirted the timber along it for some distance and then, striking a game trail at right angles, turned off on it, but left it again as I touched trails leading in the direction of the opening. Once I caught sight of two white flags and saw the deer as they took a long leap together over some tall brush. I now became more wary. It was getting on toward evening and I finally retraced my steps in the direction of camp after missing two good shots because I was not ready. At length I stopped in a trail to listen, and seemed to hear the muffled sound of chopping in the direction of the camp. While thus engaged I caught the sound of light hoofs pounding the ground and suddenly in the path a buck appeared, coming full tilt directly toward me. As I raised my gun I inadvertently called out “whoa”; he stopped short as I fired low on his neck, bringing him to the ground.

He was too heavy for me to pack or drag as he was, and I was glad that no one was around to see the awkward way in which I opened him with my pocket-knife and rid him of entrails and blood. He was still too heavy to pack, so I let him drain and scraped the blood from his coat; then, with much difficulty I cut off his head as near the ears as possible.

I knew how to pack a deer, for I had seen the process. I cut through the second joints of the front feet to the muscles, then slipped my knife down between the bone and muscles to the hoof joint. By inserting these bones through the thin part of the hind legs a lock is made to swing over the shoulder. I carried the deer in this fashion and my entry into camp was spectacular. I held a reception with all the honors. After the carcass had been duly inspected I was directed to turn it over to the company cook.

Our route now led direct toward the foothills of the Coteau des Prairies. We were leaving the timbered lake country of western Minnesota and entering the region of the great plains. There was a tang in the air and the very herbage was odorous of the range that attracts wild game.

Soon we came in view of Big Stone Lake, with Lake Traverse near by, with the Browns’ homestead looming like a gem amid its background of green hills. Lake Traverse, I was told, is the source of the Red River of the North, which runs very straight to Hudson Bay, while the waters of Big Stone Lake flow in the opposite direction, toward the Mississippi.

At our noon camp in the foothills a troop of Minnesota volunteer cavalry passed by in irregular column. Impatient to regain their homes after dreary service in the Dakota foothills, they would not wait for any formal turning over of the garrison, but skipped out bag and baggage, leaving a quartermaster to attend to the details. They were a soldierly-looking lot of men, and though roughly clad and mounted seemed fit for service in the field. Under their slouched black hats they took in “us regulars” as merely Uncle Sam’s unit to form their relief. I should have liked much to talk with them and gain some knowledge of the life and country ahead of us.

Later in the day we rounded the point of a hill and beheld the long-looked-for Fort Wadsworth, nestling between two small lakes and surrounded by a mere embankment of earth. We soon marched in and were assigned to one of the company quarters which had been vacated by our Minnesota friends.

Fort Wadsworth belonged to the usual type of frontier post, having a square parade ground surrounded on one side by a set of officers’ quarters and offices, with log quarters for three companies of troops and stables and corrals completing the other sides of a square. The aspect it presented was cheerless enough, with not a tree nor a foot of cultivated ground.

The nearest post to the westward was at Devil’s Lake, but there was not a settlement anywhere in the country nearer than those we had left behind in Minnesota. The region was devoid of both Indians and big game, other than a few white-tail deer in the sparse timber of the adjacent foothills.

Early in the autumn the captain of my company, who was also quartermaster and commissary, sent for me and said: “Corporal, you will take three six-mule teams and wagons and proceed to Sauk Center,...