- 383 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

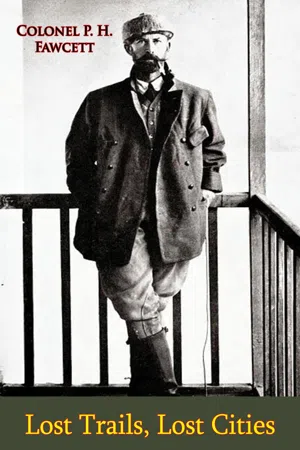

Lost Trails, Lost Cities

About this book

A chronicle of adventure and discovery in the green, deadly world of the jungle.

This extraordinary first-hand account of seven explorations into the heart of the lost world of the Amazon Basin and its mountain ramparts has been made available for publication after more than a quarter of a century's silence. On his eighth and final expedition, Colonel P. H. Fawcett vanished into the jungle wilderness; to this day his fate is unknown. Before he began his last trip he set down the story of the expeditions he had completed, and his son, Brian Fawcett, here presents it together with a summary of the attempts to solve the mystery of his father's disappearance. Colonel Fawcett was an explorer in the great tradition. He believed that somewhere in the unmapped heart of South America were the ruins of cities whose discovery would confirm many Indian legends that had come down from the days of the conquistadores. Trained in the exacting techniques of exploration-survey, he accepted an opportunity to determine the boundary line between Bolivia and Peru, and in 1906 set out on the first of his expeditions. It and the ones that followed over the next fifteen years have become classics of exploration; Colonel Fawcett combined the discipline of a scientist-engineer with the imaginative daring of a man not afraid to gamble his life on a bold conjecture.

In 1921 he set down the narrative of his first seven trips. When he failed to return from the eighth, publication was delayed until it became certain that he would never be able to complete his manuscript. But the reader will find here a wholly engrossing story of a great search written with modesty and great skill, the work of a brave and mature man who possessed both a purpose and a dream. The result is a book which will remain a classic in its field.

This extraordinary first-hand account of seven explorations into the heart of the lost world of the Amazon Basin and its mountain ramparts has been made available for publication after more than a quarter of a century's silence. On his eighth and final expedition, Colonel P. H. Fawcett vanished into the jungle wilderness; to this day his fate is unknown. Before he began his last trip he set down the story of the expeditions he had completed, and his son, Brian Fawcett, here presents it together with a summary of the attempts to solve the mystery of his father's disappearance. Colonel Fawcett was an explorer in the great tradition. He believed that somewhere in the unmapped heart of South America were the ruins of cities whose discovery would confirm many Indian legends that had come down from the days of the conquistadores. Trained in the exacting techniques of exploration-survey, he accepted an opportunity to determine the boundary line between Bolivia and Peru, and in 1906 set out on the first of his expeditions. It and the ones that followed over the next fifteen years have become classics of exploration; Colonel Fawcett combined the discipline of a scientist-engineer with the imaginative daring of a man not afraid to gamble his life on a bold conjecture.

In 1921 he set down the narrative of his first seven trips. When he failed to return from the eighth, publication was delayed until it became certain that he would never be able to complete his manuscript. But the reader will find here a wholly engrossing story of a great search written with modesty and great skill, the work of a brave and mature man who possessed both a purpose and a dream. The result is a book which will remain a classic in its field.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Topic

Personal DevelopmentSubtopic

Travel1906-1909

CHAPTER III — PATH TO ADVENTURE

“DO you know anything about Bolivia?” asked the President of the Royal Geographical Society.

Its history, like that of Peru, had always fascinated me, but beyond that I knew nothing of the country, and said so.

“I’ve never been there myself,” he said, “but its potential wealth is enormous. What has been exploited up to now is not much more than a scratch on the surface. One usually thinks of Bolivia as a country on the roof of the world. A great deal of it is in the mountains; but beyond the mountains, to the east, lies an enormous area of tropical forest and plains not yet by any means completely explored.”

He took a large atlas from the side of his desk and fingered over the pages.

“Here you are, Major—here’s about as good a map of the country as I have!” He pushed it over to me and came round to my side of the desk to point out its features. “Look at this area! It’s full of blank spaces because so little is known of it. Many of the rivers shown here are guesswork; and the places named along them mostly no more than rubber centres. You know it’s rubber country?

“The eastern frontier of Bolivia follows the River Guaporé up from Corumbá to Villa Bella, at the confluence of the Mamoré River, where the Beni becomes the Madeira, and eventually flows into the Amazon. North it runs along the Abuná, to the Rapirrar, and then overland to the River Acre. All this northern frontier is doubtful, as accurate surveys have not yet been made of it. The western frontier comes down to the Madre de Dios and along the Heath—a river that has not been explored to its source—then continues south and crosses the Andes to Lake Titicaca. On the southern frontier there is the Chaco, which is the border with Paraguay, and, further westwards, the frontier with Argentina—the only border which has been definitely fixed.

“Now, up here in the rubber country along the Abuná and the Acre, where Peru, Brazil and Bolivia meet, there is considerable argument about the frontier, and so fantastically high is the price of rubber now that a major conflagration could arise out of this question of what territory belongs to whom!”

“Just a minute!” I interrupted. “All this is most interesting—but what has it got to do with me?”

The President laughed. “I’m coming to that. First of all I want you to get the picture....

“The countries concerned in the dispute about the frontiers are not prepared to accept a demarcation made by interested parties. It has become necessary to call in the services of another country which can be relied on to act without bias. For that reason the Government of Bolivia through its diplomatic representative here in London has requested the Royal Geographical Society to act as referee, and to recommend an experienced army officer for the work on Bolivia’s behalf. As you completed our course in boundary-delimitation work with outstanding success, I thought of you at once. Would you be interested in taking it on?”

Would I! Here was the chance I had been waiting for—the chance to escape from the monotonous life of an artillery officer in home stations.

The War Office had frequently promised that boundary-survey work might come my way if I acquired the training, and so I had gone to great trouble and expense to make myself competent. Time passed without my hopes being fulfilled, and I began to doubt those promises. Now, from an unexpected quarter, there came the offer I most desired! My heart was pounding as I faced the President, but with an effort I assumed an air of caution.

“It sounds interesting, certainly,” I remarked, “but I’d like to know a little more about it first. It must be more than just survey work.”

“It is. What it really amounts to is exploration. It may be difficult and even dangerous. Not much is known about that part of Bolivia, except that the savages there have a pretty bad reputation. One hears the most appalling tales of this rubber country. Then there’s the risk of disease—it’s rife everywhere. It’s no use trying to paint an attractive picture for you, and I hardly think it’s necessary, for if I’m not mistaken there’s a gleam in your eye already!”

I laughed. “The idea appeals to me—but it depends on whether the War Office will agree to second me.”

“I realize that,” he replied. “You may have some difficulty, but with the backing of the R.G.S. I have no doubt they will release you in the end. After all, it’s a wonderful chance to enhance the prestige of the British Army in South America.”

Naturally I accepted the offer. The romantic history of the Spanish and Portuguese conquests, and the mystery of its vast unexplored wilds, made the lure of South America irresistible to me. There were my wife and son to consider, and another child was on the way; but Destiny intended me to go, so there could be no other answer!

“It would have surprised me had you refused,” said the President. “I shall recommend you at once, then.”

One difficulty after another cropped up, and I became anxious about the chances of being released. However, it was finally arranged, and I left Spike Island with the hope that before long my wife and the children would be able to join me in La Paz. With a young assistant named Chalmers, we embarked on the North German Lloyd flagship Kaiser Wilhelm der Grosse in May 1906, and sailed for New York.

This ship was at that time the last word in luxury liners, but as travel of this sort had little appeal for me I was bored, and quite indifferent to the overfed passengers who sprawled about the decks. There were gales and fog; we nearly collided with a roving iceberg, invisible till it was almost too late to avoid it. A high-pressure cylinder burst and left us rolling for hours in the troughs of a terrific sea; but it all happened in the brief space of a week, and soon we were in New York.

The energy and bustle were things I had never known before. Accustomed to the calm deliberation of the English and the solemn dignity of the East, America at first shocked me. We were not allowed beyond the area of the docks, and so my impressions were mainly of noise, advertisements, and reporters by the score. The speed of street traffic, the fussiness of the tugs in the harbour as they pushed and shouldered the innumerable railroad car-floats and lighters, the incessant shouting, all jarred on my nerves; but to soothe them again there was the truly wonderful sight of that unique skyline, the green of Governors Island, and the elegant tracery of the Brooklyn Bridge.

We had a brief glimpse of New York and no more. The same afternoon we boarded the S.S. Panama, and the Statue of Liberty sank out of sight astern. This ship was the antithesis of the floating palace we had left, for it was a dirty Government ship full of “Diggers” bound for the Isthmus of Panama. White-collar workers, adventurers, toughs, would-be toughs, and leather-faced old scoundrels crowded every foot of available space, and when walking up and down the deck we had to dodge foul squirts of tobacco-juice. Their chief occupations were drinking and playing ruinous crap games, and the noise that went on all the time made my study of Spanish grammar a difficult matter. There were sourdoughs from the Klondike, Texas Rangers, and gunmen from south of the border, boomer railroad men with stacks of forged service letters, a few prostitutes, and fresh young college boys on their first adventure. They were all good fellows in their way, and each played his part, however small, in making that masterpiece of engineering, the Panama Canal. To Chalmers and myself it served as a useful introduction to an aspect of life we had not hitherto known, and much of our English reserve was knocked off in the process.

The port of Cristobal was known as Aspinwall in those days, and ships tied up to a long jetty stretching far out into Limon Bay. Beyond the docks lay Colon, more restricted than it is now but otherwise much the same. Liberally sprinkled with Hindu curio shops and saloons, it was composed largely of alleys where drunken laughter and the tinkling of pianos seemed to uphold its reputation for having more brothels than any town of its size in the world. Notices shouted at you to come in and have a drink! Sailors were everywhere, in all stages of intoxication, reeling from saloon to saloon, and from brothel to brothel. Quarrels flared up on street corners and died down again; here and there a scuffle attracted an interested group of spectators; down some side street a screaming prostitute would fling curses at a perro muerto, or patron who left without paying the score. There was no attempt at keeping the peace —the Panamanian police knew better than to try!

Alongside the front street ran the tracks of the Panama Railroad, and the fussing yard engines moved up and down with scarcely a pause, their bells clanging monotonously. Every now and then there came from beyond the town the long-drawn wail of a chime whistle, and a freight or passenger train would come romping in from across the Isthmus and draw up in the station with thumping air compressor and the soft sigh of releasing brakes.

We left the jetty in a buggy driven by a somnolent Jamaican, bumped over the railroad tracks, and clip-clopped along the edge of Colon to the station. The town was comparatively quiet at this time of day, except for the activity in the railroad yards and a subdued tinkle of glasses from the saloons, with perhaps an occasional oath or a shout of laughter. By day it is too hot to do anything but laze and sleep, and it is after sundown that the town wakes up. It rests all day and dances all night, like the fireflies in the pandemonium of the Chagres woods.

The rail journey across to Panama City gave us our first sight of the forest of tropical America—the buttressed, ghostly pale tree boles; the hanging tangle of lianas and moss; the almost impenetrable scrub and bush. Fever was rampant, and in one of the way stations through which we clattered I noticed the platform piled to the roof for its whole length with black coffins!

For us, Latin America began in Panama City. There was little attempt at sanitation, the smells were almost overpowering, yet the narrow streets and overhanging balconies were not without their charm. In the Plaza was the “Gran Hotel”—it is always “Grand,” “Royal,” or “Imperial,” however humble, and what it lacks in status it makes up in grandiose title! This one turned out to be an insect paradise; and the proprietor was greatly annoyed when I pointed out that the bed-linen in my room was overdue for the laundry.

“Impossible!” he roared with a flurry of gesticulation. “All the linen goes to the laundry at least once a month. If you don’t like it, there are plenty of others who would be glad to have the room. Every bed in my hotel is occupied, some by two—even three—and every bathtub as well! Yours is a big room, and I am losing money by letting you have it to yourself.”

There was nothing I could say. After all, every hotel was overcrowded.

Everywhere the lottery vendors hawked their ticket strips, cafés and saloons abounded, and from the balconies we were ogled by scantily clad ladies. Down by the shore was a sea wall forming the outer defence of a crowded jail, and here you could stroll in the evening, toss coins to the scrambling prisoners beneath, and sometimes see an execution by firing squad. With so much entertainment it was impossible to be bored.

We were glad to leave Panama, all the same, when at length the time came to embark on a Chilean ship—a narrow-gutted, rakish vessel with side-loading holds, and superstructure running from the extreme stern to within a few feet of the clipper bow—designed for coast service in little dog-hole ports where no dock facilities existed. The best ships on the Coast were those of the Pacific Steam Navigation Company of Liverpool, and had time permitted we should have preferred to wait for one of these, for their officers were a cheerful lot, with a genius for deck golf, and the knack of making the trip pleasant for the passengers. But we were on the trail of Pizarro, and nothing else mattered.

As a boy I was held spellbound by the romantic histories of the Conquests of Peru and Mexico, and the long-dormant yearning to visit these countries was now about to be satisfied. Like many other readers of Prescott’s masterpieces, my sympathies were not with the daring and rapacious Spaniards risking all for gold, but with the Incas for the loss of their ancient civilization which might have told the world so much.

Guayaquil was at this time a veritable penthouse! One evening we steamed up the Guayas River through dense clouds of mosquitoes, which invaded cabins and saloon alike, penetrated to every corner of the ship, and stung us mercilessly. I had never known anything like it before. The agonies of Pizarro and his followers must have been beyond description when these pests crept out of scratching range and bit under their sheltering armour! Guayaquil’s appalling lack of sanitation had much to do with the yellow-fever endemic. As the anchor roared down into the black mud of the filthy river, evil-smelling bubbles burst upwards—and I was reminded of Malta. But Yellow Jack hardly seemed to worry the people, for the streets were crowded, trade was brisk, and well-kept launches lined the wharves. A new Minister to London was due to leave in a north-bound steamer of the same line as ours, so numerous Ecuadorian flags waved over the city’s public buildings, and we watched him with his gorgeously uniformed staff played aboard by brass bands.

The clean freshness of the Pacific welcomed us when the fever-haunted Guayas River vomited us out on its muddy tide. Rounding Cape Blanco, where the giant blanket fish leap and drum and where every wave is split by the twin triangles of sharks’ fins, we came to the Northern Peruvian port of Paita. This was a nondescript village of wooden houses, standing at the foot of unbroken sandhills, and here we were fumigated with formaldehyde for our indiscretion in visiting Guayaquil.

Salaverry was the next port of call—one of those places where you should if possible go ashore, but generally can’t. It is not far from Trujillo, itself one of the oldest Spanish settlements on the Coast and site of an ancient Chimu city and burial grounds, dug up over and over again in search of treasure. The tradition is that somewhere in this vicinity lies hidden the treasure of the “Big Fish.” The “Little Fish” was discovered about two hundred years ago and is said to have realized twenty million dollars for its lucky finder! “Big Fish” is worth considerably more, and is believed to contain the emerald god of the Chimus, cut from a single stone eighteen inches high.

Callao is the port of Lima, capital of Peru, and here we lay offshore, the ship rolling her rusty bottom out in the huge swell some distance from the embarcadero, or landing-stage. Soon we were invaded by shouting, struggling boatmen who fought their way to the ladders, and from their rocking launches bargained with shore-going passengers, breaking off every now and then to hurl streams of invective at one another. To jump from ladder to launch in this bedlam was anything but easy. One moment the lowest step of the ladder would be at a giddy height above the crowding boats, then there was a scramble to avoid a ducking as the sea came foaming up almost to deck level. It was a matter of biding your time, and then jumping, in the hope that the chosen launch would be there when you landed! Hugh jellyfish—medusæ—drifted about on the surface and as far down in the clear water as the eye could see.

Once ashore we found a choice of three railways for the nine-mile trip to Lima. There was the famous Central of Peru, masterpiece of that indefatigable engineer, Henry Meiggs; the “English Railway,” opened to traffic in 1851 and claimed as the first in South America; and an electric line whose interurban cars even at that time could do a mile a minute.

Lima turned out to be a fine city, with admirable shops and wide avenues to bear witness to the progressive policy of the late President Pierola, whose object it was to beautify the place. Motorcars were yet few, and the principal conveyance was the victoria, though in every one of the main streets horse cars crawled along tracks set in the cobbles. Almost anything could b...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- FOREWORD

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- MAPS

- NOTE TO READER

- PROLOGUE

- 1906-1909

- 1900-1914

- 1915-1925

- EPILOGUE BY BRIAN FAWCETT

- GLOSSARY

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Lost Trails, Lost Cities by Colonel P. H. Fawcett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Personal Development & Travel. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.