- 143 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Serial Universe

About this book

In this book I have tried to give the reader a bird's-eye view of the territory covered by the theory called 'Serialism'. Some of the chapters, greatly condensed, have been delivered in lecture form to the Royal College of Science (Mathematical Society and Physical Society). But the main outline of the subject is, I believe, clear enough to be appreciated by those who have no special technical knowledge. Where all is fog, a blind man with a stick is not entirely at a disadvantage. In my case, Fortune presented me with a stick; and I have used this with considerable temerity. Certainly, it has led me somewhere possibly only into the roadway, where I shall be run over by a motor-bus full of scientific critics. But, if I have crossed safely to the other side, then I should like to express my gratitude to Mr J. A. Lauwerys of the University of London, whose continuous encouragement has been the chief factor which has kept me tapping along.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I—THE THEORY OF SERIALISM

CHAPTER I—MEANING OF A ‘REGRESS’

A ‘series’ is a collection of items linked together, chain-fashion, by some recurrent relation. The notion of series has reference, always, to some underlying unity; this is implicit in the fact that the separated items are related to one another.

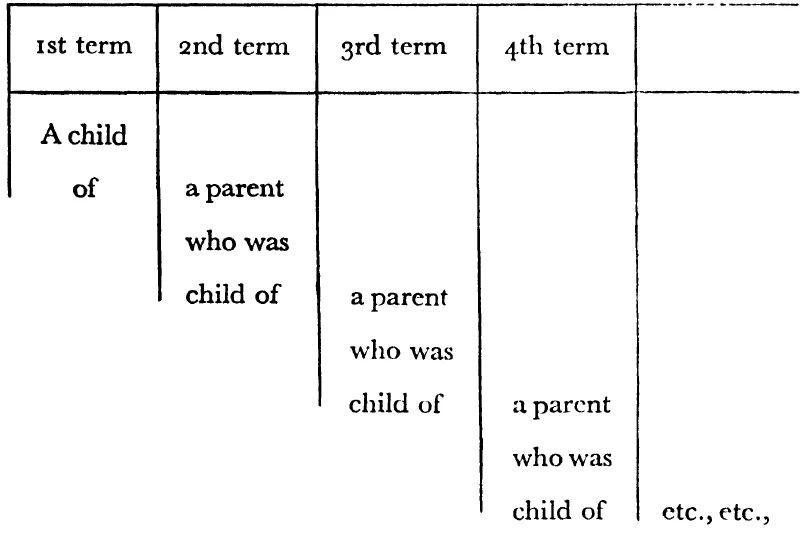

The distinctive items of a series are called its ‘terms’. For example, if we regard a child as a creature who had a parent who had a parent who had a parent, etc., etc.; the child is the first term, his parent the second term, and his grandparent the third term of a receding series. And, if we tabulate that series thus:

the relation between the terms becomes readily apparent.

We know, from various biological indications, that this particular sequence stretches back to before the dawn of history. But the old-time philosophers thought that it must either recede to a time infinitely remote, or have been started by some magical act of creation. And it is rather interesting to consider what were their grounds for that assumption.

If we look at the first term in the table, we find there an individual to whom we have allotted only one character—the character of being a child. Now the fact that every child has or had a parent is merely a truism; it is asserted already in the meaning attaching to the word ‘child’. And, taken by itself, it does not compel us to entertain the notion of remoter ancestors. But suppose we go on to the second term. We come to a person who is declared to possess a double character—a person who is both parent and child. As a parent, he is related to the first-term individual already examined; and, as a child, he must be related to some ancestor not yet taken into account. Now, the early philosophers supposed, wrongly, that it was a matter of logical necessity for every parent to be also a child. If that had been true, the series, obviously, would have been bound to extend backward to infinity.

The point—the point which is so often over-looked—is this: The extension of a simple series to infinity involves some necessarily dual character in its terms. But, to discover that dual character, we must trace the series as far as its second term. A study of the first term (such as the child in the above example) with its single character, will yield us only half the required information. And it may be noted that the third and remaining terms do no more than repeat the information already asserted by the second term. All the remoter individuals in the purely imaginary example we have taken would have possessed the double character of being both parent and child; but we could have discovered that from an examination of the second term alone.

In brief: Every simple series to infinity is the expression of some logical fact which is asserted in the second term but not in the first.

And, as we shall see later, it may be impossible to exaggerate the importance, to the human race, of this very simple characteristic of a simple infinite series.

Now, a series may be brought to light as the result of a question. Someone might enquire, ‘What was the origin of this man?’, or a child learning arithmetic might set to work to discover what is the largest possible whole number. The answer to the first question has not yet been ascertained: the answer to the second can never be given. It will be seen, however, that the reply in each case must develop as a series of answers to a series of questions. In the first instance, we reply that the man is descended from his father; but that only raises the further and similar question, ‘What was the origin of his father?’. In the second case, the child will discover that 2 is a greater number than 1; but he is compelled to consider then whether there is not a number greater than 2—and so on to infinity. A question which can be answered only at the cost of asking another and similar question in this annoying fashion was called, by the early philosophers, ‘regressive’, and the majority of them regarded such a ‘regress to infinity’ with absolute abhorrence.

Their attitude is easy to understand. They wished to regard the universe as something completely explicable. To admit that there were questions with answers which receded as a rainbow recedes, was, in their opinion, to admit, before they started, that their task of explaining everything was foredoomed to failure. Then, again, a considerable number of the early philosophers supposed that the universe must be, at bottom, something extremely, even childishly, simple; a naïve theory which involved that to every question there must be a simple and straightforward answer. This provided another reason for the ancient dislike of regressions. And we must add to the list that very numerous class which wished, and still wishes, from motives of policy, to divide the world sharply into things which are comprehensible and things which are incomprehensible. To such persons, a question which is answered by an ‘infinite regress’ is anathema, because it provides, very obviously, a class between the two divisions.

In brief, it was universally recognised that a regress might be logically incontrovertible; men moulded their lives and their sciences upon the immense stock of reliable information provided by the study of these incompleted series of questions and answers; and yet the regress to infinity was looked upon as being, in some fashion apparent only to intuition, not actually untrue, but not precisely that aspect of the truth which it was the business of philosophy to discover.

They were quite unable to put this feeling into words. They wandered off into loose talk of complexities’, which was a dubious charge, and of ‘contradictions’, which was a libel unjustified in anyone with any pretensions to intelligence—for a contradiction produces no regress at all, and the whole trouble about the infinite regress is its damnable logicality. If the truth of the premiss (i.e., the double character of the second term) is acknowledged, the regress becomes mathematically inevitable. Yet the feeling has persisted to this day: it crops up afresh whenever some new regression, to the sight of which we have not grown accustomed, is discovered. And Bradley, perhaps, gave it its nearest approach to verbal expression when he said, ‘Reality cannot be an infinite regress’.

The answer, I think, is this:

The truth or falsity of Bradley’s dictum depends upon the meaning it attaches to the word ‘reality’. If it refers to reality pure and undefiled by any attempt at translation into terms of human comprehension, his statement, probably, is true (though you must not ask me to give reasons for that belief). But if the word means reality in the scientific sense,—rational cum empirical reality,—then the assertion is, defi...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- PREFACE

- INTRODUCTION

- PART I-THE THEORY OF SERIALISM

- PART II-GENERAL TEST OF THE THEORY

- PART III-SPECIAL TESTS OF THE THEORY

- PART IV-CONCLUSION & APPENDIX

- APPENDIX

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Serial Universe by John William Dunne in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Philosophy & Ethics in Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.