This is a test

- 270 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

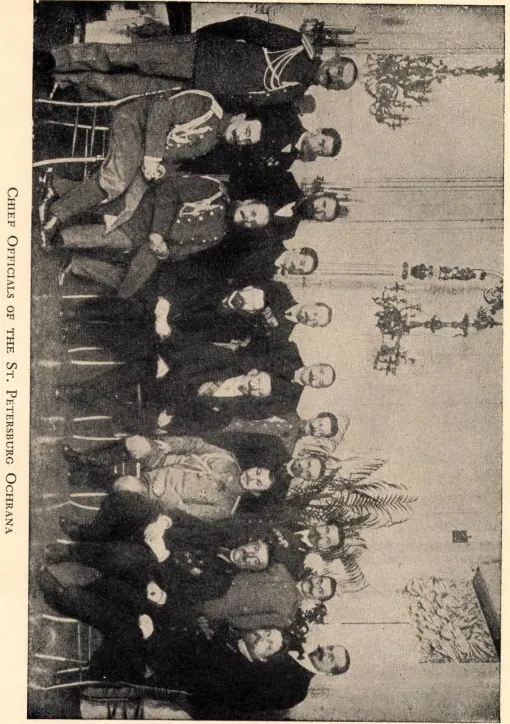

Originally published in 1930, these are the memoirs of the last Tsarist chief of police, Okhrana, who was arrested by the revolutionaries, refused to be a Bolshevik spy, escaped to France, became a railway porter and died penniless.The book tells of the part he played in Rasputin's death and his experiences during WWI and the Revolutions, and the comparison between the Okhrana and the Cheka, the Soviet secret police, in which he describes a kinder, gentler Okhrana.Richly illustrated throughout.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Ochrana by A. T. Vassilyev in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Geschichte & Russische Geschichte. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

GeschichteSubtopic

Russische GeschichteCHAPTER I

Functions of the Ochrana—The External Agency—Qualities required of Police Spies—Technique of Observation—Myednikov’s School—His Special Section—Suppression of a Bomb Factory

MUCH that was mysterious, enigmatical, and dreadful was associated in the mind of the Russian people with the term Police Department. For great sections of the population this office signified frankly a phantom of terror, of which the most improbable tales were told. Many people seriously believed that in the Police Department the unhappy victims of the Ochrana{3} were dropped through a hole in the floor into the cellar, and there tortured.

Of course there was not the slightest foundation for such legends. The Police Department never perpetrated the bestial cruelties fantastically ascribed to it. On the contrary, its measures were always strictly legal. Nevertheless, this authority was really of terrifying import to certain people; but, of course, these were not the peaceful population. They were those adversaries of the Empire who, being not yet very numerous, were only tentatively but surely aiming at the diffusion in Russia of the poisonous gospel of Socialism.

It is to be ascribed to the propaganda of these scoundrels that the Secret Political Police acquired such an evil reputation, for the revolutionaries naturally did their utmost to bring discredit upon their bitterest enemy in order to hamper as far as possible its effective activity. They had once contrived to smuggle one of their agents, an individual named Voiloshnikov, into the Third Section of the Police Department, and consequently to bring about much confusion. Appropriate measures were taken to prevent such things occurring again; and the revolutionaries, in their impotent rage, thereafter made it their business to accuse us persistently and at every opportunity of cruelty and illegality in our procedure.

However, I personally, and many of my predecessors, can most emphatically declare that these accusations were absolutely groundless. The correctness with which the Ochrana did its work is also vouched for by the testimony of that distinguished Public Prosecutor and model of uprightness, Muravyov, who after the Revolution acted as President of the Special Commission which investigated closely the conduct of the Tsarist authorities.

It would take too long if I were to set about tracing here the development of the Ochrana. I therefore confine myself to the statement that the first beginnings of a Political Police were made in the reign of Peter the Great. It was at that time that the Chancellor Biron set up a secret political office, whose functions in certain respects coincided with those undertaken afterward by the Ochrana. During the nineteenth century there finally arose the Third Section, since become so well known, from which the Special Corps of Gendarmerie and the Ochrana originated.

In the last decades of the nineteenth century the principal task of the Ochrana was to keep a check upon revolutionaries among the lower classes, and especially among the students, who had turned in large numbers to ideals subversive of the State. Later it was the active propaganda of the Socialists that assumed prominence, and with them were associated the followers of Tolstoi’s Communistic teachings. The growth of revolutionary tendencies in the Empire obliged the authorities to increase the efficiency of the Ochrana and, for that purpose, to strengthen more and more its machinery.

The duties of the Secret Police were very exactly defined. They consisted in the investigation of all movements directed against the State, and in their destruction. Further, the Ochrana had also upon occasion to concern itself with various other crimes, such as murder and robbery, and, in time of war, with matters of espionage. In all its operations it was a question of police action pure and simple: the Ochrana’s job was to discover the evil-doers. Their punishment was not its concern, but that of the judicial authorities.

Accordingly all investigations had to be handed over sooner or later to the Public Prosecutor. And the Ochrana had only the right to keep suspects under arrest for not more than two consecutive weeks. After the lapse of that period the prisoner had either to be released or to be transferred to the category of those undergoing regular imprisonment on remand. Attached to each Ochrana section were several public prosecutors, who followed the course of the inquiries and answered for the legality of all measures taken.

There was only one form of extra-judicial punishment, and that was administrative banishment; sentences of up to five years could be pronounced. This measure was, it must be admitted, frequently but leniently applied; and latterly exiles were allowed, if they desired, to go abroad instead of going to Siberia. If they took advantage of that option they were never permitted to return.

It is perfectly ridiculous to assert that the Ochrana ever, of its own authority, had a political prisoner executed. Without exception it was only the regular tribunals that could pronounce the death sentence, and this was nearly always in connexion with the crime of murder; the Ochrana had nothing at all to do with such sentences. Only in those districts where military law had been proclaimed could executions be carried out as they are all over the world—without a regular judicial sentence, and by the order of the military officer commanding. Thus the Governor-General of Warsaw once condemned a group of Anarchists to death; they had carried out a series of sanguinary crimes.

The supreme control of all investigations of a criminal or political nature was centred in the Police Department of the Home Office. This was organized in numerous sections, of which the Records Section was specially important. There were kept exact data with regard to all persons who had ever come under the observation of the Criminal or Political Police. Thus the authorities had at their disposal very carefully compiled archives containing not merely photographs, records of fingerprints and anthropometric details, but also the nicknames and aliases used by the conspirators among themselves.

The Chief of the Police Department occupied an extraordinarily responsible post; and, considering the political importance of this office, the appointment of the Chief of Police for the time being was reserved for the Home Secretary (Minister of the Interior). Whenever this Minister retired, the Chief of Police relinquished his post at the same time, so that the new Minister might appoint a man in the enjoyment of his personal confidence.

The machinery of the Political Police embraced the centres stationed all over the Empire of the so-called Special Corps of Gendarmerie and the actual Ochrana, which functioned only in the larger localities. As a rule, Ochrana sections were brought into being in those towns in which the revolutionary parties had set up their committees. The Ochrana offices had at their disposal their special Records Sections and their own libraries containing all revolutionary and other prohibited printed works. For it is to be noted that all the higher officials of the Ochrana had always to be well acquainted with revolutionary literature, and to have completely at their command the history of all subversive movements.

Moreover, the Ochrana had at its disposal a staff of trained specialists; it had its photographers, its handwriting experts, and in many districts even its own Jewish specialists competent in all matters of Jewish faith, who supplied the Ochrana with many a valuable hint.

Suspected persons might be kept under observation by two fundamentally different methods, which were for the most part applied so as to supplement each other as far as possible. These were, on the one hand, the so-called system of External Observation, and, on the other, the Internal or Secret Agency.

The former consisted in the observation of all suspects by police spies or informers, who were officially designated Agents of the External Service. These agents formed special detachments under the command of officials trained expressly for this service. Their duties were to keep an eye upon suspicious characters in the streets, theatres, hotels, railway trains, and similar places of public resort, and to endeavour to discover all possible details concerning the mode of life of such persons and the company frequented by them.

The service of these informers was exceptionally exhausting and perilous. Only such men were adapted for it as were endowed with a considerable measure of staying power and of quick perceptive faculties, for the revolutionaries knew, of course, of the existence of the secret agents, and sought to baffle and mislead them by every conceivable trick. Frequently informers, recognized as such by the Terrorists, were murdered while they were performing their duty.

An official agent in the course of years acquired quite a peculiar capacity: once he had made a careful study of a photograph the features of the original were so impressed upon his memory that he never forgot them, and any person whom he had once seen would be infallibly identified by him among hundreds of others.

Of course, the secret agents generally assumed some sort of disguise: they served as porters, door-keepers, caretakers, newspaper-sellers, soldiers, officers, or railway officials. It was a special art to wear these disguises so that they might not be noticed. And the Ochrana kept for such purposes a regular store of its own, with clothing and uniforms of every kind, just as it maintained a permanent supply of horses and vehicles. In the headquarters of the Moscow Ochrana there was a special court for the numerous agents disguised as cab-drivers, where they were continually passing in and out.

The public has, generally speaking, entertained exaggerated ideas of the number of spies in Tsarist Russia. It was widely assumed that every town of any size was flooded with hundreds of secret agents, and that in St. Petersburg there were thousands. In reality the whole body of secret agents under the command of the Ochrana all over Russia did not number many more than a thousand men, and in St. Petersburg there were only about a hundred of them altogether. The Foreign Agency, the efficiency of which was so much talked of in revolutionary circles, had to carry on its operations with a very small personnel. Only when it was a question of observing perhaps a Socialist congress or a conspiracy abroad were a few agents occasionally sent out from the Ochrana in St. Petersburg and Moscow to strengthen the service in Western Europe.

The duties of the External Agency and the means to be employed in all cases by the agents are shown in detail in the orders of the Police Department. These orders were for a time kept strictly secret, but in spite of all precautions they came finally to the knowledge of the revolutionaries. This circumstance alone makes it permissible for me, in what I shall have to say in the following pages, to refer to these instructions, which provide in any case the most appropriate means of giving the reader authentic information as to the operation of the Ochrana.

The Police Department lays it down as a necessary preliminary to any successful piece of work that the agents should, above all, be able to impress firmly upon their memory the features of the individuals to be kept under observation. The spy is expressly recommended to take advantage of every opportunity of practising and developing this important faculty, and to cultivate the habit of calling back to mind, with his eyes closed, the characteristic features of any person, after having taken one brief glance at him. Along with the face, they were to observe accurately stature and build, gait, colour of the hair, and carriage of the shoulders.

All points noted were to be entered in the report book, and this was to be submitted every week to the head of the section to which the spy was attached. Special record folios, with red, green, and white leaves, afforded the chief official of the detective service added facilities in overlooking the materials that were continually coming in.

Every month the chiefs of the Ochrana sections drew up the lists of persons who were being watched, all known details about them being stated, as well as the reasons for keeping them under observation.

Written and telegraphic communications between spies and their superiors were never to be conducted in ordinary language, but chiefly in the jargon of business correspondence. If, for example, an agent wanted to report that the man he was tracking had gone to Tula, the telegram would run: “Goods required arrived Tula.”

As for the personal qualities to be possessed by the agents, the instructions to which I have before alluded require all agents of the detective service to be politically and morally reliable, honest, sober, bold, adroit, intelligent, patient, prudent, upright, obedient, and of good health. Individuals of Polish or Hebrew descent were, on principle, excluded from any kind of employment in the External Service. All newly appointed agents were to have it explained to them how very important their office was for the security of the State, and then to be sworn in in the presence of a priest.

The first business of the new recruit was to make himself thoroughly acquainted with the town in which he was to be stationed, especially with drinking saloons, beer-gardens, taverns, and houses with an access to two or more streets. Then he must know all about droshkies and motors, their stances and their fares; the hours of arrival and departure of the main long-distance trains; times for beginning and stopping work in the various factories and workshops. He must memorize the uniforms of the various military units, of schoolboys and students. During his period of training he had, to begin with at least, to hand in daily a report in writing, showing his progress in those branches of knowledge. On these reports depended the decision whether he had, or had not, any aptitude for service in the Police.

Not till then was he entrusted with the execution of some actual observation work, and, to start with, even that only under the guidance of some older and more experienced official, whose duty it was to point out his faults. At the same time his political reliability was tested by other agents, who engaged him in conversation and sought to gain his confidence.

Nor was the private life of the secret agent a matter of indifference. He might indeed be a married man, but it was always regarded as rather an unfavourable circumstance if he showed any excessive devotion to his family. For dangerous and responsible commissions such men were just as ill-suited as those fellows who were inclined to form intimate associations with women of easy manners and with other doubtful acquaintances.

Of course, it was firmly impressed upon every agent entering the Service that whatever he got to know during the course of his duties was to be regarded as strictly official and secret, and must never be betrayed to anyone.

For certain reasons it had appeared expedient to indicate persons under observation not by their real names, but by certain nicknames. Whenever an agent was brought by his work into contact with a suspected person he had to give him at once some such nickname, which thereafter wou...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- ILLUSTRATIONS

- INTRODUCTION

- AUTHOR’S INTRODUCTION

- CHAPTER I

- CHAPTER II

- CHAPTER III

- CHAPTER IV

- CHAPTER V

- CHAPTER VI

- CHAPTER VII

- CHAPTER VIII

- CHAPTER IX

- CHAPTER X

- CHAPTER XI

- CHAPTER XII

- CHAPTER XIII

- CHAPTER XIV

- CHAPTER XV

- CHAPTER XVI

- CHAPTER XVII

- CHAPTER XVIII

- CHAPTER XIX

- CHAPTER XX

- CHAPTER XXI

- CHAPTER XXII

- CHAPTER XXIII

- CHAPTER XXIV

- CHAPTER XXV

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER