- 292 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

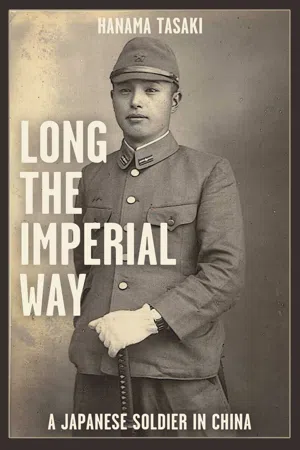

Long the Imperial Way

About this book

Long the Imperial Way, first published in the U.S. in 1950, is a realistic portrayal of life in the Japanese Imperial Army during the late 1930's. The book is based on the author's own experiences during the three years he served as a private in China (author Tasaki, raised in Hawaii, wrote the book in English). The book details the rites ingrained in the soldiers, demanding sacrifice and unquestioning obedience to superior officers. Scenes include the burning of Chinese villages, harsh beatings of the First Year Soldiers by those with more seniority, and unrestrained pillaging.

Long the Imperial Way remains one of the few books which provide insight into the experiences of the typical Japanese soldier in the period just prior to World War Two.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1 — Kao-liang Fields — Kōryan batake

The vastness of the countryside was terrifyingly depressing. There were simply no distinctive features to it like hills, or rivers, or woods. There was just the plain, and it extended and extended until it was lost in the hazy mist of the horizon. To be sure, there were the villages here and there partly hidden under scraggly clumps of trees, and the waving fields of kaoliang and wheat, and the roads winding among them, but they were sprawled indiscriminately, as if some giant had angrily tossed them out of a bag and let them fall whichever way they wanted. To one born and raised on an island they were not distinguishable landmarks but incongruous parts of the endlessness and monotony of the plain.

Private Takeo Yamamoto of the Hamamoto infantry company of the Japanese Army gazed with awe and a depressing feeling of futility at this expansive panorama of the North China continent. He was squatted, well hidden among the tall, thick grass on a low hill overlooking the plain. The hill was the only distinct break in the geography of this district for as far as one could see. The soldier held a rifle propped against his shoulder, for he was on sentinel duty and certainly not on the hill to enjoy the scenery.

Takeo was used to the wide spaces and incongruity of the continent by now (for he had been serving in China for over half a year), but he had never seen anything in such a scale as this and had to take hold of himself from time to time to keep his deeply ingrained sense of duty from becoming lost in an aimless contemplation of the surrounding. But his mind kept going astray, and his eyes kept wandering off into space....Now, the scenes at home were comforting. One had any number of different, interesting things to hold one’s attention or even to keep one entertained. There were hills everywhere with neat rows of verdant trees on them or symmetrical patches of cultivated land on their slopes. Valleys always had sparkling streams and rivers running through them over interesting formations of rock. Then there were the minutely squared-off rice paddies. Towns and roads were where everyone would expect them to be and not scattered haphazardly.

It is hot, Takeo thought, his mind wandering off into space again. There was a hot midday sun shining down from a clear autumn sky, and there was nothing over Takeo’s head but some grass he had tied to his cap to camouflage himself.

This time, however, his mind did not wander far, for a train’s whistle sounded in the distance and jarred him back to his sense of duty. He swept his eyes hurriedly along the railway which ran across the plain and past the hill directly below him. There was a thin slanting column of black smoke against the skyline far to the left, and it was approaching swiftly. Takeo could hear the faint chug-chugging of the locomotive, growing stronger with each beat.

The tracks themselves were mostly hidden by the tall stalks of kaoliang which grew thickly on both sides of them, and Takeo peered intently at the tasseled tops of the crowded grain for any signs of movement underneath. The main duty of the guard Takeo was standing was to keep a careful watch for guerrilla bands out to harm the railway, and they had been told that it was a valuable line connecting the capital with Suchow, a vital North China base they had captured only a month ago. The kaoliang fields offered ideal cover for the guerrillas, who had already overturned a train and cut the line at several places. All of their raids had been conducted at night, but the soldiers on sentinel duty were warned that the enemy might attempt similar attacks in broad daylight anytime now, for they must have been most certainly emboldened by their successes at night.

Satisfied by the normal movement of the kaoliang fields under a light breeze which was blowing across the plain, Takeo next looked at the narrow dirt paths leading toward the tracks. Only the usual desultory movement of farmers was to be discerned, and he saw no groups of appreciable size which could merit even his slightest suspicion. Completely at ease, he gazed fondly on the train which came thundering out of the fields under a trailing canopy of black, belching smoke to rush noisily across the tracks below him and to disappear again into the fields. But the black banner of smoke from the locomotive was visible for some time over the even top of the grainfields, and as it lurched jerkily but resolutely across the endless plain it looked futile and weak, and even comical, until it disappeared in the mist over the horizon.

After the smoke was completely lost to sight, the train whistled again, and the long plaintive wail of the whistle, wafted ever so faintly across the clear autumn air, awoke a sudden feeling of forlornness and homesickness in Takeo. It came so suddenly, it gripped his heart and almost choked him. As he looked longingly at the spot over the horizon where the train’s smoke had disappeared, he asked himself, Who will be helping the harvest at my home this year?

His mother had written him in her last letter, “Please put yourself at ease, because the Young People’s Corps has promised to help the harvest.”

His parents were quite old, and it would be hard on them to bring the harvest in all by themselves, even if theirs was a small farm of only six tan (an acre and a half). Takeo was their only son, and he had been doing all the heavy work on the farm for some time until he had been called into the army. Like most farms in Japan, their farm, too, was dispersed in strips over a wide area, covering hills and valleys.

For the hundredth time he told himself, If they only had an ox, it would do the work in my place.

Not very long after he had entered the army, Takeo had made up his mind that he would save enough money from his army pay to buy an ox for his parents. Fortunately, he did not smoke or drink, and he had been able to save nearly all of the five-yen-fifty he had received monthly during his four months of basic training in the barracks at home and the eight-yen-eighty he had begun to receive after coming to the front as a full-fledged private nearly six months ago. He had now over fifty yen in the bank, and when he had left home, a good two-year ox had cost from a hundred fifty yen to two hundred yen....He was not going to learn to smoke and drink, now that he was in the army, as so many of his comrades were doing, and if he had to stay at the front even after the necessary sum was saved, he would send it home and give his parents the pleasure of buying the ox.

“Is there nothing amiss?” The low, gruff voice of Private First Class Tanaka immediately behind Takeo almost made him jump.

“No, sir!” Takeo answered quickly. “A little while ago, a train passed. Otherwise, there has been no change.”

Takeo had been so lost in his favorite contemplation on the purchase of an ox that he had not heard the Private First Class creeping softly up through the grass behind him. Private First Class Tanaka was the head of the Sentinel Post on the hill and was usually in the well-camouflaged dugout shelter about fifty yards to the rear, which was the rest station, with the four other soldiers who made up the post. But the Private First Class was a strict sentinel-post leader and supervised every sentinel change and kept prowling about all the time to keep the sentinels on their toes.

“At what hour did the train pass?” the Private First Class asked.

“Yes, sir,” Takeo answered and found himself at a loss to answer further, for they had had strict orders to check the exact time any train passed under the hill and Takeo had forgotten to do so.

“I have asked, What hour did the train pass?” Private First Class Tanaka repeated angrily.

“Yes, sir,” Takeo stammered and confessed, “I did not look at my watch.” His eyes were kept constantly to the front, for he was not supposed to relax his vigil while answering a superior, but Takeo could feel the angry eyes of his superior glaring disgustedly at him from behind.

Private First Class Tanaka was a Second-Year-Soldier, or a soldier in his second year of service. Takeo and his other comrades, who had entered the service at the same time as he, were First-Year-Soldiers, or soldiers in their first year of service. The first year of service in the army was supposed to be a sort of period of apprenticeship, and the First-Year-Soldiers were held in complete servility by their superiors, who included the Second-Year-Soldiers, the Third-Year-Soldiers, and the Reserves. The Second-and Third-Year-Soldiers were regulars who had been serving their compulsory two-year term in the conscription army when the war on the continent had started, and they had been dispatched immediately to the front. The Reserves were men who had already completed their service in the conscription army and been discharged once, but who had been called back to the colors with the outbreak of war.

“You are a good-for-nothing soldier.” Private First Class Tanaka’s voice sounded derisively behind Takeo.

“Yes, sir,” Takeo answered stiffly.

“Repeat the Rules of the Sentinel Post,” the Private First Class demanded.

“Yes, sir,” Takeo answered, and he now felt a little relieved, for he had memorized well the Rules which had been handed them the previous day when they had first learned that they were coming to this post. Takeo recited in a confident voice:

“First, this Sentinel Post shall be called the Helmet-Mountain-Sentinel-Post.

“Second, since there are remnants and guerrilla bands in the neighborhood, one must constantly watch the surrounding and be especially careful of the railway.

“Third, if one recognizes anything amiss, one should immediately report it to the Sentinel-Post Leader and be especially careful that he is not seen by the enemy.”

It was a beautiful recitation, accomplished without a single flaw, and even the Private First Class seemed to be satisfied as he grunted, “All right. Be careful,” and turned and went away. Like most of his comrades, Takeo had only gone to elementary school, but he had a good head for memorizing, which stood him in valuable stead in the army, for a great part of the soldier’s task in the army was memorizing.

Even after the Private First Class had gone, Takeo felt for some time the alertness and tension the sudden visit of his superior had instilled into him. His eyes roaming over the countryside now had purpose back of them. He looked at the village about a kilometer on the other side of the railroad tracks, where his platoon was quartered, and although he could not see its streets, he examined its surrounding carefully for any suspicious-looking groups among the natives leaving and entering it. Next, he looked carefully at the roads leading to the station house beside the railway below him where the rest of his squad under Corporal Jiro Sakamoto was quartered. There were some natives leading a short train of loaded donkeys approaching the tracks, and he watched them carefully while the sentinel standing in front of the station stopped them and examined the loads on the donkeys. After some time the natives were allowed to pass, and they crossed the tracks and disappeared among the waving kaoliang.

The hypnotism of the plain, however, was not to be resisted long, and soon Takeo’s eyes were gazing blankly once more at the wide, entrancing spaciousness of the plain. He let go of his rifle and let it rest by itself against his shoulder. The alertness of his mind was once again replaced by the fatalistic depression of a moment ago.

What is death? Takeo asked himself all of a sudden, or, rather, his mood suggested the question to his mind. It was not like a philosopher or student deliberately pondering on this mightiest of questions since the beginning of time, but the question simply suggested itself out of his mood at that moment, and Takeo thought nothing more of it than if he had asked himself, What are we going to have for dinner? On the other hand, too, it was as if the great space before him had asked him the question. In any case, it was the space which had created the mood that called the question to mind.

If we die, we are going to the Yasukuni Shrine. We are going to become gods, Takeo told himself, merely repeating a popular sentiment in the country at that time. But, somehow, Takeo was not satisfied. The Yasukuni Shrine was only a locality in the country, and he was sure death was something bigger.

Takeo had come to think a great deal about death since his arrival at the front. He had already participated in a big campaign, the Suchow campaign, and he had seen many deaths as well as himself narrowly escaping death many times. Death had seemed at home nothing much more than the burning of incense and the reading of Sutras by Buddhist priests, but at the front this comforting conception had been jolted badly by the sight of many mangled and disfigured corpses.

I wonder if there is a heaven and a hell? Takeo next asked himself. The Buddhist priests usually said there was, but, How did they know? and Takeo did not trust them. Or were they reincarnated or reborn into something else after death, as his grandmother used to say? Therefore, she had never eaten the flesh of any living thing nor killed even the tiniest insects, for she had claimed every living thing on earth possessed the soul of a former human being. But this too was hard to believe, however much Takeo had loved his grandmother and trusted her.

Maybe death was just what it seemed—the end of everything! On the battlefields he had seen corpses which had been flattened by tanks, and, again, he had helped burn the corpses of comrades killed in combat, in order to get the ashes to send home to their families, for in the Japanese Army all the dead were cremated and their ashes sent home in little wooden boxes wrapped in white cloth. De...

Table of contents

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Publisher’s Note

- CHAPTER 1 - Kao-liang Fields - Kōryan batake

- CHAPTER 2 - Entertainment - Yokyō

- CHAPTER 3 - Discipline - Shugyō

- CHAPTER 4 - March - Kōgun

- CHAPTER 5 - Propaganda Mission - Sembu

- CHAPTER 6 - Billeting - Shukuei

- CHAPTER 7 - Enemy Attack - Tekishū

- CHAPTER 8 - Reduction to Ashes - Kaijin

- CHAPTER 9 - Leave Day - Gaishutsu

- CHAPTER 10 - Comfort - Ian

- CHAPTER 11 - The Kempei - Kempei

- CHAPTER 12 - Merriment - Yūen

- CHAPTER 13 - Punishment - Chōbatsu

- CHAPTER 14 - Drinking Party - Shuen

- CHAPTER 15 - In the Ship’s Hold - Sensō kanwa

- CHAPTER 16 - Rededication - Yōhai

- CHAPTER 17 - Opposed Landing - Tekizen jōriku

- CHAPTER 18 - Easing Up - Kentai

- CHAPTER 19 - Mud - Deinei

- CHAPTER 20 - Death Struggle - Shitō

- CHAPTER 21 - Cigarettes from the Throne - Onshi no tabako

- CHAPTER 22 - Native Soil - Kokoku no tsuchi

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Long the Imperial Way by Hanama Tasaki in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & European History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.