This is a test

- 183 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

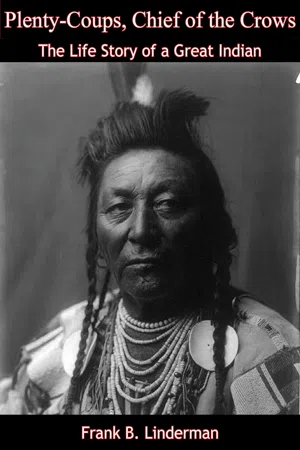

In his old age, Plenty-Coups (1848-1932), the last hereditary chief of the Crow Indians, told the moving story of his life to Frank B. Linderman, a well-known western writer who had befriended him.First published in 1930, Plenty-Coups is a classic account of the nomadic, spiritual, and warring life of Plains Indians before they were forced onto reservations. Plenty-Coups tells of the great triumphs and struggles of his own life: his powerful medicine dreams, marriage, raiding and counting coups against the Lakotas, fighting alongside the U.S. Army, and the death of General Custer.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Plenty-Coups, Chief of the Crows by Frank B. Linderman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias sociales & Biografías de ciencias sociales. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Ciencias socialesSubtopic

Biografías de ciencias socialesI

PLENTY-COUPS, aided by Coyote-runs and Braided-scalp-lock, seated himself in round his cabin on Arrow Creek. “I am glad you have come, Sign-talker,” he said, his nearly sightless eyes turned upon me. “Many men, both of my people and yours, have asked me to tell you the story of my life. This I have promised to do, and have sent for you; but why do you wish to write down my words, Sign-talker?”

The least suspicion that his story might count against him or his people would result in my failure to get a truthful tale of early Indian life on the plains. My answer must be honestly and carefully made.

“Because I do not believe there is any written story of an Indian chief’s life,” I said. “If you tell me what I wish to know, and I write it down, my people will better understand your people. The stories which I have written of Esacawata and the Crows have helped white children to know the children of your tribe. A better understanding between your people and mine will be good for both. Your story will help the men of my race to understand the men of your race.”

Magpies jabbered above the racks of red meat hung to cure in the dry air, and the Chief’s dogs, jealous and noisy, raced below them. By gift, the dogs would get very little of the meat they guarded; the magpies, more by theft.

“You are my friend, Sign-talker. I know your heart is good. I will tell you what you wish to know, and you may write it down,” said Plenty-coups, at last. “I would have Coyote-runs and Plain-bull sit with us each day,” he added. “I am an old man, and they will help me to remember.”

“Good!” I agreed, glad of their company. They had known Plenty-coups all their lives and were different as two men could be. Plain-bull, thin and spare, was retiring; his badly scarred forehead was a reminder of strenuous life. Coyote-runs was tall and sturdy, his voice deep, and his manner aggressive. Both were old men, and both expressed satisfaction at the Chief’s decision to tell me his story.

“If you do not tell all—if you forget—I will touch your moccasin with mine,” Coyote-runs warned the old Chief, seriously. “We trust Sign-talker,” he said. “Begin at the beginning. You are sunk in this ground here up to your armpits. You were told in your dream that you would have no children of your own blood, but that the Crows, all, would be your children. Your medicine-dream pointed the way of your life, and you have followed it. Begin at the beginning.”

“He is more than eighty,” I thought, when the Chief’s face, upturned to the speaker, was in profile to me, its firm mouth and chin, its commanding nose and wide, fighting forehead, models for a heroic medallion. The broad-brimmed hat, with its fluttering eagle feather, hid the contour of his head. His gray hair fell in braids upon his broad shoulders. He had been a powerful man, not over-tall, and was now bent a little by the years. His deep chest and long arms told me that in his prime Plenty-coups had known few physical equals among his people. Could he, with one eye entirely gone and the other filmed by a cataract, distinguish Coyote-runs, I wondered.

He removed the hat from his head, laid it upon the grass beside him, and gripping the arms of the chair to steady himself, stood up. We all rose. His fine head lifted, he turned as though his nearly sightless eyes could see the land he so much loves. “On this beautiful day, with its flowers, its sunshine, and green grass, a man in his right mind should speak straight to his friends. I will begin at the beginning,” he said, and sat down again.

The company fell silent, as though waiting for me. Coyote-runs began filling his pipe, his eyes not watching his fingers. A score of questions came to my mind, but I banished them in the interest of order. “Where were you born?” I asked, while meadow larks trilled in the hay field.

“I was born eighty snows ago this summer [1848] at the place we call The-cliff-that-has-no-pass,” said Plenty-coups slowly. “It is not far from the present site of Billings. My mother’s name was Otter-woman. My father was Medicine-bird. I have forgotten the name of one of my grandmothers, but I remember her man’s name, my grandfather’s. It was Coyote-appears. My other grandmother, a Crow woman, married a man of the Shoshone. Her name was It-might-have-happened. She was my mother’s mother.”

Years ago I had heard that Plenty-coups was not a full-blooded Crow, but was part Shoshone. I knew that with the tribes of the Northwest a mother’s blood determines both tribal and family relationship, but here was an opportunity for verification that ought to stand.

“With the blood of a Shoshone in your veins, do you consider yourself a full-blooded Crow?” I asked.

“Yes,” he replied. “You are a white man and are thinking of my Shoshone grandfather, but remember that his woman, my grandmother, was a Crow and that all the women of my family were Crows.”

“What are your earliest remembrances?” I asked, feeling that I had interrupted him with my question.

He smiled, his pipe ready to light. “Play,” he said happily. “All boys are much alike. Their hearts are young, and they let them sing. We moved camp very often, and this to me, and the other boys of my age, was great fun. As soon as the crier rode through the village telling the people to get ready to travel, I would find my young friends and we would catch up our horses as fast as the herders brought them in. Lodges would come down quickly, horses would be packed, travois loaded, and then away we would go to some new place we boys had never seen before. The long line of pack-horses and travois reaching farther than we could see, the dogs and bands of loose horses, all sweeping across the rolling plains or up a mountain trail to some mysterious destination, made our hearts sing with joy.

“But even in all this we were not completely happy, because we were obliged to travel with the women and loaded travois. Young men, riding high-spirited horses whose hoofs scarcely touched the ground, would dash past us, and, showing off before the young women, race out of our sight. Then our mothers would talk among themselves, but so that we might hear.

“‘That young man on the white horse is Little-wolf, son of Medicine-woman,’ one would say admiringly. ‘He is brave, and so handsome.’

“‘Yes, and he has already counted coup and may marry when he chooses,’ another would boast.

“‘Think of it!’ another mother would exclaim. ‘He has seen but twenty snows! Ah-mmmmm! Perhaps she would lay her hand over her mouth, which is the sign for astonishment.

“This talking between our mothers, firing us with determination to distinguish ourselves, made us wish we were men. It was always going on—this talking among our elders, both men and women—and we were ever listening. On the march, in the village, everywhere, there was praise in our ears for skill and daring. Our mothers talked before us of the deeds of other women’s sons, and warriors told stories of the bravery and fortitude of other warriors until a listening boy would gladly die to have his name spoken by the chiefs in council, or even by the women in their lodges.

“More and more we gathered by ourselves to talk and play. Often our talking was of warriors and war, and always in our playing there was the object of training ourselves to become warriors. We had our leaders just as our fathers had, and they became our chiefs in the same manner that men become chiefs, by distinguishing themselves.”

The pleasure which thoughts of boyhood had brought to his face vanished now. His mind wandered from his story. “My people were wise,” he said thoughtfully. “They never neglected the young or failed to keep before them deeds done by illustrious men of the tribe. Our teachers were willing and thorough. They were our grandfathers, fathers, or uncles. All were quick to praise excellence without speaking a word that might break the spirit of a boy who might be less capable than others. The boy who failed at any lesson got only more lessons, more care, until he was as far as he could go.”

Age, to the Indian, is a warrant of experience and wisdom; white hair, a mark of the Almighty’s distinction. Even scarred warriors will listen with deep respect to the counsel of elders, so that the Indian boy, schooled by example, readily accepts teaching from any elder. He is even flattered by the attention of grown men, and is therefore anxious to please.

“Your first lessons were with the bow and arrow?” I asked, to give him another start on his boyhood.

“Oh, no. Our first task was learning to run,” he replied, his face lighting up again. “How well I remember my first lesson, and how proud I felt because my grandfather noticed me.

“The day was in summer, the world green and very beautiful. I was playing with some other boys when my grandfather stopped to watch. ‘Take off your shirt and leggings,’ he said to me.

“I tore them from my back and legs, and, naked except for my moccasins, stood before him.

“‘Now catch me that yellow butterfly,’ he ordered. ‘Be quick!’

“Away I went after the yellow butterfly. How fast these creatures are, and how cunning I In and out among the trees and bushes, across streams, over grassy places, now low near the ground, then just above my head, the dodging butterfly led me far before I caught and held it in my hand. Panting, but concealing my shortness of breath as best I could, I offered it to Grandfather, who whispered, as though he told me a secret, ‘Rub its wings over your heart, my son, and ask the butterflies to lend you their grace and swiftness.’ ”

The Indian of the Northwest (Montana and the surrounding country) believes that the Almighty gave each of His creations some peculiar grace or power, and that these favors, at least in part, may be obtained from them by him, if he is studious of their possessor’s habits and emulates them to the limit of his ability. Here, I believe, is where the white man was first led to declare that the Indian believed in many gods. I have studied the Indian for more than forty years and have tried to understand him. He believes in one God, and has told me many times that he had never heard of the devil until ‘‘the Black-robes brought him” to his country. He does, however, believe there are created things which possess evil powers. Some of the tribes do not like the owl, believing him wicked. Others do not look upon him in this light, but respect him.

“‘O Butterflies, lend me your grace and swiftness!’ I repeated, rubbing the broken wings over my pounding heart. If this would give me grace and speed I should catch many butterflies, I knew. But instead of keeping the secret I told my friends, as my grandfather knew I would,” Plenty-coups chuckled, “and how many, many we boys caught after that to rub over our hearts. We chased butterflies to give us endurance in running, always rubbing our breasts with their wings, asking the butterflies to give us a portion of their power. We worked very hard at this, because running is necessary both in hunting and in war. I was never the swiftest among my friends, but not many could run farther than I.”

“Is running a greater accomplishment than swimming?” I asked.

“Yes,” he answered, “but swimming is more fun. In all seasons of the year most men were in the rivers before sunrise. Boys had plenty of teachers here. Sometimes they were hard on us, too. They would often send us into the water to swim among cakes of floating ice, and the ice taught us to take care of our bodies. Cold toughens a man. The buffalo-runners, in winter, rubbed their hands with sand and snow to prevent their fingers from stiffening in using the bow and arrow.

“Perhaps we would all be in our fathers’ lodges by the fire when some teacher would call, ‘Follow me, and do as I do!’ Then we would run outside to follow him, racing behind him to the bank of a river. On the very edge he would turn a flip-flop into the water. Every boy who failed at the flip-flop was thrown in and ducked. The flip-flop was difficult for me. I was ducked many times before I learned it.

“We were eager to learn from both the men and the beasts who excelled in anything, and so never got through learning. But swimming was most fun, and therefore we worked harder at this than at other tasks. Whenever a boy’s father caught a beaver, the boy got the tail and brought it to us. We would take turns slapping our joints and muscles with the flat beaver’s tail until they burned under our blows. ‘Teach us your power in the water, O Beaver!’ we said, making our skins smart with the tail.”

A woman wearing a pink calico dress and a red shawl came now to give the Chief a small bag full of something. I did not learn its contents. In her presentation the woman spoke rapidly and in a high-pitched voice, as though she were either excited or angry, and in his acceptance the Chief said not a word. He took the bag, laid it beside his hat on the grass, and the woman vanished. Nor was there any comment by either Coyote-runs or Plain-bull, and since the woman had used no signs with her rapid speech I could only hope that the visit had not seriously diverted the Chief from his story. But it had not. He began again, as though he had not broken off.

“I remember the day my father gave me a bow and four arrows. The bow was light and small, the arrows blunt and short. But my pride in possessing them was great, since in spite of its smallness the bow was like my father’s. It was made of cedar and was neatly backed with sinew to make it strong.”

I knew he would take for granted that white men know how an Indian holds a bow and arrow, and I did not intend to permit this. There has been too much discussion over the proper position of the hands for me to let the opportunity to question him pass.

“Show me how you held your bow and arrow,” I said.

He looked around his chair, as though searching for something he could not see. Coyote-runs guessed what was wanted, and, picking up a small cottonwood limb, quickly fashioned a rude bow. They both laughed merrily while Plain-bull found a smaller stick to serve as an arrow, and each in turn took a squint at its crookedness and shook his head. But it would do, and the Chief stood up with the improvised weapon. Gripping it firmly with his left hand, he deftly placed the arrow with his right, the index and second fingers straddling the shaft and, ...

Table of contents

- Title page

- DEDICATION

- FOREWORD

- I

- II

- III

- IV

- V

- VI

- VII

- VIII

- IX

- X

- XI

- XII

- XIII

- XIV

- XV

- XVI

- XVII

- XVIII

- XIX

- XX

- AUTHOR’S NOTE

- REQUEST FROM THE PUBLISHER