This is a test

- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Long before history began to be recorded, man strove constantly to get plants that would produce greater amounts of food with less labor. Sometimes he obtained this improvement by increasing the food-producing ability of an existing plant, at other times by selecting a more capable new plant. Hybrid corn is the greatest example in recent time of increasing the value of a food-bearing plant by improving one already in common use. The development of hybrid corn is truly one of the most important advances made in all the thousands of years since man first began cultivating special food-bearing plants.What is hybrid corn, and how does it differ from the corn grown before it was developed?

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access The Hybrid-Corn Makers by A. Richard Crabb in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Science General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER I—Eternal Servant

MAN IS A GUEST on this earth of the green plants. Of all our planet’s creatures and objects, the green plants alone are on dealing terms with the world’s only great source of energy and power—the sun. In spite of all our efforts to crack their monopoly these green plants still hold an exclusive franchise in the vital business of gathering and storing the sun’s energy as food and fiber without which neither man nor any of his animals could survive for more than a few hours. This was true ten thousand years ago, and it is just as true now in what we speak of as the atomic age, a somewhat misleading reference since life on our earth has from the beginning been sustained by the sun’s energy generated by the process we now popularly refer to as “atom splitting.”

Every green plant is, in effect, a power pipeline extending directly to the sun. Most plants pipe in this precious sun’s energy as a miserable little trickle; others make it available more abundantly. A very few bring us the sun’s power in a veritable gush, and discovering one of these rare green plants is like tapping a geyser of life and energy that never can run dry.

This is the story of the discovery of one of these rare superplants, hybrid corn, and of the men who fashioned it. Since the hybrid-corn makers worked with a plant already of worldwide importance and of ancient origin, the story will be more interesting if we take a sweeping glance at eon in its unique role as a builder of civilization.

The American Indian developed nearly two dozen plants of present-day economic importance, including both white and sweet potatoes, pumpkins, beans, chocolate, squashes, tomatoes, peppers, peanuts, pineapples, tobacco, cocoa, cotton—and corn, greatest of all his food-providing plants. Corn was known to the Caribbean tribes who introduced it to Christopher Columbus as “mahiz,” from which our word maize was derived. Scouts sent by Columbus to explore what is now the Island of Cuba became the first white men of record to see corn. On November 5, 1492, the first corn fields they encountered stretched across the Caribbean countryside continuously for eighteen miles.

How did the Indians develop corn? No one knows. Although the wild ancestors of many of our other major food and fiber-yielding crops have been found, no wild or clearly primitive corn has ever been discovered—although scientists throughout the world have spent more time attempting to fathom the mystery surrounding the origin of corn than has been spent on the historical background of any other plant.

Regarding the origin of corn, most plant scientists now look with increasing favor upon the theory widely discussed in the nineteenth century and recently revived—with extensive new evidence to support it by two noted botanists of the present day, Paul Mangelsdorf of Harvard and R. 6. Reeves of the Texas Agricultural Experiment Station. This view holds that the cradle of corn is to be found in the extreme southwestern part of the great Amazon River basin in South America. Some of this region has not yet been explored, and there is a remote possibility that wild corn may yet be found in one of the inaccessible valleys of eastern Bolivia. The first Indians to plant and cultivate corn were probably those living in what is now Peru, Bolivia, and northern Chile.

In this area, it is believed, the new plant first supplied food so abundantly that it provided the energy and leisure to plant and build the first of several ancient American civilizations. This corn-supported empire of the Incas developed a culture and a standard of living that rivaled those of ancient Egypt, Babylon, and Greece.

As corn moved north, it touched off a number of later and also highly developed Indian civilizations in Latin and North America. The empires of both the Mayans in what is now Guatemala in Central America and the Aztecs in Old Mexico were in some respects even more advanced than that of the Incas. The march of maize continued northward into what is now the southwestern United States, and other Indian cultures blossomed in the Arizona New Mexico area. Then corn crossed the desert barriers into the central and northeastern areas of North America so that at the time Europeans reached the New World they found varieties of corn being grown generally east of the Rocky Mountains and as far north as southern Canada.

The coming of the spice-seeking Columbus broke the seal of New World isolation and permitted corn to continue its march throughout the other continents.

The Indians, highly dependent on maize, were wholly responsible for its survival. Had North and South American Indians neglected to plant, hoe, and harvest corn and at the same time discarded their reserve supplies of seed during any one of the thousands of years they preserved it, the maize as we know it would have disappeared from the earth, for there is not a single recorded instance of corn having ever survived in the wild. Not only did the Indians preserve corn for themselves and for us; they developed and improved it to such a point that even today most corn being grown strongly resembles the maize that was passed on to other races by these red men. All five of the common types of corn in use today—popcorn, sweet corn, flour, flint and dent corn—were developed by the Indians.

Equally surprising hat been the rapidity and degree to which this maize crop has been accepted by other races following its discovery by the Columbus expedition. Entering most other countries after the great food plants of the Old World were already solidly entrenched, this Indian corn quickly won a position of worldwide importance.

The men from Columbus’ ships came ashore in the New World early in the fall of 1492. They thought they had reached the shores of India; consequently they gave maize the name “Indian corn” because it was raised by “Indians” and somewhat resembled their own cereal crops called “corn” since ancient times. Columbus returned to Spain early in .1493, carrying with him the first maize ever seen in Europe. That year corn grew in the royal gardens of Spain and within two generations was growing as a food crop in every country of sixteenth-century Europe. In less than a century, Indian corn had moved completely around the world. Today the maize of the American Indians has become a crop of virtually all nations. So great has been corn’s relative indifference to changes in environment that every week of the year maize is being planted, cultivated, and harvested at some point around the earth. Corn is filling a role of such wide usefulness that it has won for itself a place apart from all other cultivated plants of the world.

Although the rapid spread and acceptance of corn throughout the world has added an intensely interesting and significant chapter to the romance of maize, corn has found its greatest usefulness and service right in North America. Corn has figured just as prominently in life on both American continents since the coming of white men as it did before, a fact that is likely to be overlooked by many of us today. The story of America under the white men has many incidents which dramatically highlight the importance and contribution of corn.

So important was the Indian’s corn to early colonists in America that the historian, Parker, concluded that “...the maize plant was the bridge over which English civilization crept, tremblingly and uncertainly, at first, then boldly and surely to a foothold and a permanent occupation of America.”

The English, who were the first Europeans to realize fully that the greatest wealth of the New World was in its soil, established their first colony at Jamestown, Virginia, in 1607. The wheat and small grains that they intended to grow in America failed so miserably that, except for their discovery of Indian corn, everyone would have starved. Fortunately Captain John Smith had mingled with the Indians enough to appreciate the value of corn and the ease with which it could be grown. Seeing the critical condition of the Jamestown Colony he allotted an acre of ground to every man and ordered him to grow corn on it, or be deprived of the protection of the fort.

The Pilgrims landed from their overloaded Mayflower in mid-November of 1620 on the New England shore. Aware that they had neither the time nor the energy to clear a new home site from the forest, they selected an Indian corn field as the place to build the white man’s first permanent settlement in New England. Food supplies brought from England were running low by the time the Pilgrims reached our shores. The scourge of hunger was soon among them. Fortunately Miles Standish and a few companions, while returning from a fruitless hunting expedition, came upon some mounds obviously built recently in which they found buried baskets of Indian corn.

In addition, the Pilgrims were able to buy eight hogsheads of maize and beans from the Indians to tide them over until their first harvests in the summer and fall of 1621. Squanto, trusted Indian friend, taught the men of the Plymouth Colony how to plant and care for corn, instructing them in such things as the preparation of the ground for planting, the use of fish in each hill fop the fertilizer so greatly needed in the moderately fertile Cape Cod soil, the number of seeds to plant in a hill, and the best time and means of cultivation.

Few of us today realize the extent to which the colonists used and depended upon Indian corn. Thomas Ash, a clerk on the English ship Richmond, visited Carolina and other New World places in 1682 and was surprised to observe the universal use made of maize. Writing of the colonists, Ash reports, “Their Provision which grows in the Field is chiefly Indian Corn, which produces a vast Increase, yearly, yielding Two plentiful Harvests, of which they make wholesome Bread, and good Bisket, which gives a strong, sound, and nourishing Diet; with milk I have eaten it dress’d in various ways...The Indians in Carolina parch the ripe Corn, then pound it to a Powder, putting it in a Leather Bag: When they use it, they take a little quantity of the Powder in the Palms of their Hands, Mixing it with Water, and sup it off: with this they travel several days. In short, It’s a Grain of General Use to Man and Beast...The American Physicians observe that it breeds good blood...At Carolina they have lately invented a way of making with it good sound Beer; but it’s strong and heady.”

With the close of the colonial period, public appreciation of corn began to decline, ironically, just as the production and use of corn began to increase by leaps and bounds. Maize yielded such bountiful harvests that we could afford to feed corn to animals that in turn produce the meat and milk foods which have now for a hundred years been the backbone of the American diet. Only vast supplies of corn, other cereal grains, and forage have made possible this rich diet for America, as approximately seven pounds of grain and forage must be fed to produce one pound of the highly nutritious meat or milk.

With the opening of the Erie Canal, connecting the big cities of the seaboard with the Lake Erie region, Buffalo, New York, surrounded with new corn country, became the nation’s livestock processing center. The Indians were rapidly pushed from their lands in the valleys of the Ohio, upper Mississippi, and Missouri Rivers during the early years of the 1800’s. Typical of the struggle of the whites to wrest away from the red men their corn grounds was the Black Hawk War of 1832.

The Sac and Fox Indians occupied what is now northwestern Illinois, southern Wisconsin, and a large part of Iowa. The center of the Sac and Fox nation was the villages situated along the Rock and Mississippi Rivers, near the sites below the present cities of Rock Island, Illinois, and Davenport, Iowa. There Indians had more than eight hundred acres under cultivation, most of which was in corn.

The whites began pressing in on the Sac and Fox Indians about 1800. In 1804 a highly questionable treaty requiring the Indians to move west of the Mississippi was drawn up in St. Louis between the Americans and two Indians who Chief Black Hawk, great leader of the Sac and Fox, said were not authorized to negotiate. Pressure upon the Indians increased constantly. During the next quarter of a century the Indians yielded territory grudgingly but bloodlessly. Illinois became a state in 1818, and matters came to a climax in 1831 after the Sac and Fox women had planted their corn along Rock River—their last crop on the corn fields of their ancestors.

Early that summer General Gaines of the United States Army issued an ultimatum to Black Hawk, giving him just two days to accept the terms of the St. Louis treaty and move his people across the Mississippi River. Although protesting vigorously, the Indians did retreat to the west bank of the Mississippi. Deprived of an opportunity to harvest their crop, the Indians were hungry during the ensuing winter, and in the spring Black Hawk and his braves recrossed the river. The Black Hawk War—in which Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis served as fellow officers—followed, and the Indians were soon decisively beaten. Victory gave the whites complete possession of the great corn lands east of the Mississippi River.

Farmers moved into these fertile areas as soon as treaties, rifles, or both had been effectively used to remove the threat of Indian troubles. The meat packing industry followed westward as the new corn lands were opened. Whereas in 1825 Buffalo, New York, had been our great meat processing area, by 1860 the packing industry was centered in the Ohio River city of Cincinnati, known in its early days as “Porkapolis,” so numerous were its swine-slaughtering plants.

This was the era of the “land whale,” when fat hogs, fed two years or more on a concentrated corn diet, supplied the oil that largely replaced the whale oil used earlier so extensively in the seaboard area of the United States. Sixteen million pounds of hog oil—each pound representing a scoopful of corn—were processed at Cincinnati in 1849 alone. Fifteen hundred men were engaged at that time making the barrels and kegs in which was shipped this oil that was used for illumination, lubrication, medicine and numerous other purposes.

One may well wonder if the Confederacy’s president, Jefferson Davis, did not reflect sadly on the fact that he had helped clear the Indians from the Illinois and Wisconsin prairies. By the time his Confederates were fighting the Civil War, those prairies had been broken, and corn was being funnelled into Chicago, in the form of livestock and grain, in such volume that Chicago was bidding for Cincinnati’s position as capital of the American livestock industry. Chicago’s P. D. Armour got his start toward fame and fortune by supplying meat from corn-fed livestock to the Union Army. In 1861 Chicago traders handled twenty-five million bushels of corn, and livestock representing many times that much corn, Feeding the Union and its armies gave Chicago such a stimulus that by 1870 it was recognized as the food center of the entire world—capital of a vast economic empire built largely on corn.

Corn growing became big business in the Civil War period and immediately after. In 1880 our farmers were raising more than thirty-four bushels of corn for every man, woman, and child in the United States.

Farmers began to feel a tremendous interest in improving their corn. The maize of the Indians, good as it was, must now be made b...

Table of contents

- Title page

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- DEDICATION

- PREFACE

- INTRODUCTION: WHAT IS HYBRID CORN?

- CHAPTER I-Eternal Servant

- CHAPTER II-Dawn on the Prairie

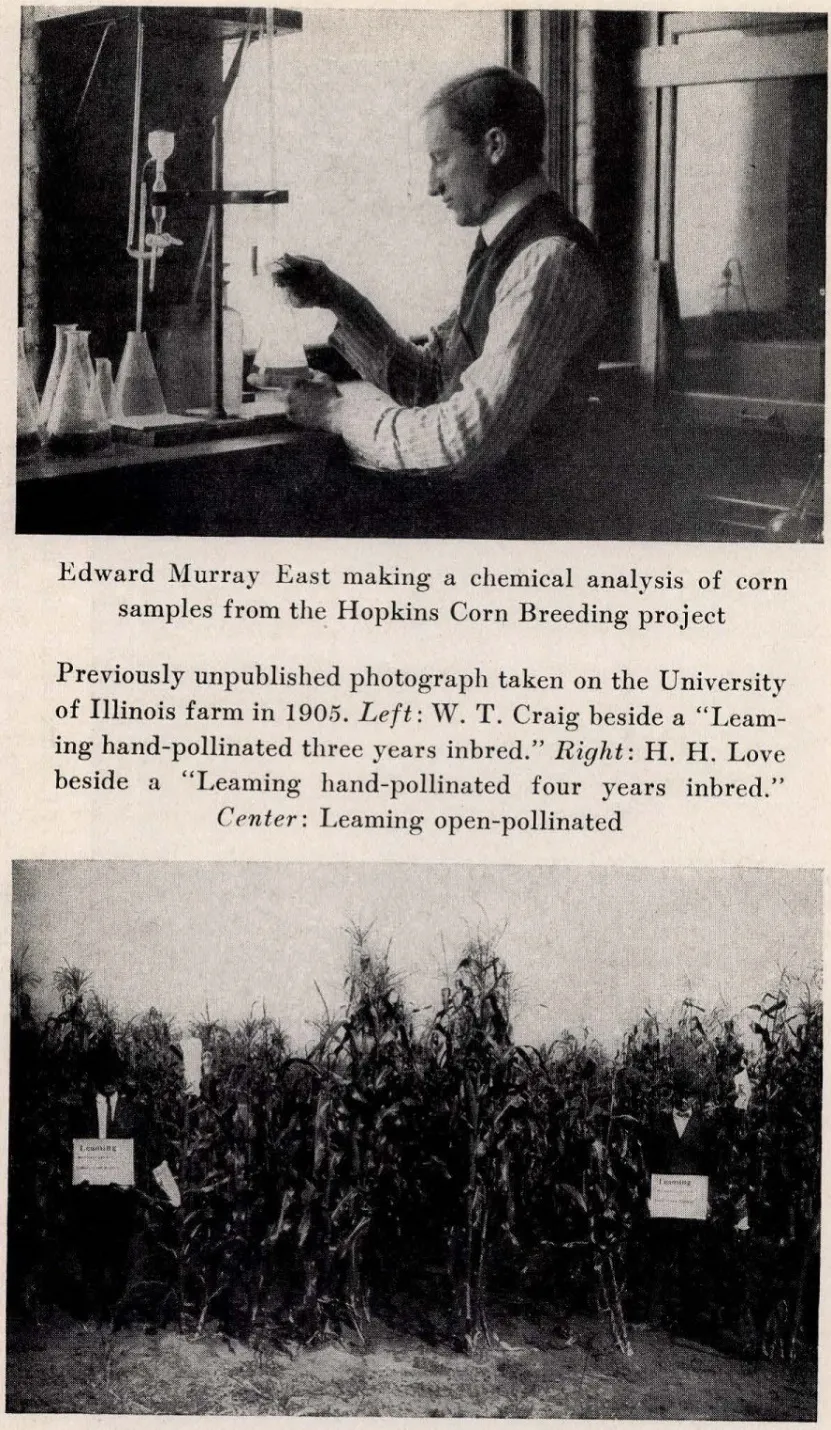

- CHAPTER III-Edward Murray East

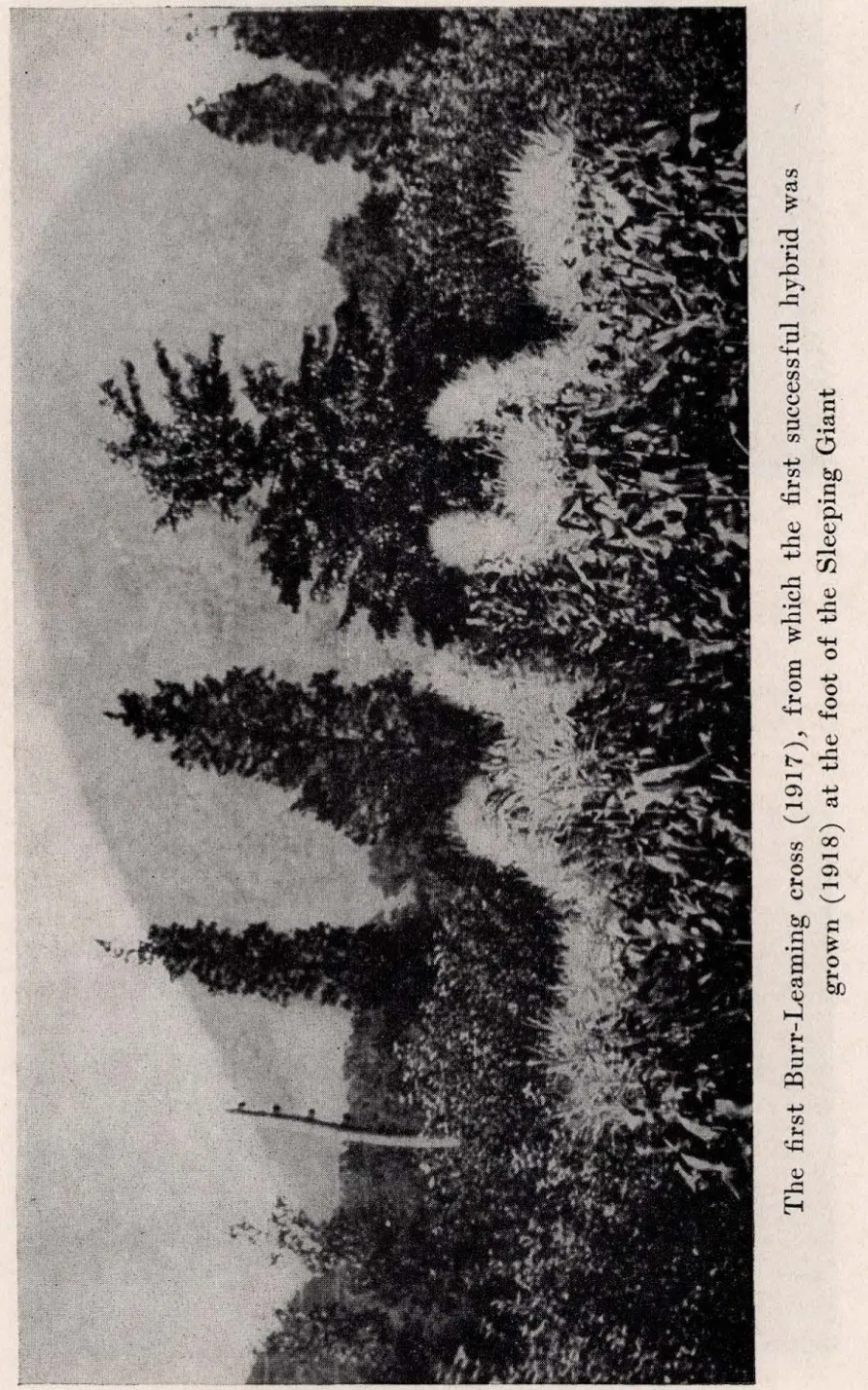

- CHAPTER IV-Land of the Sleeping Giant

- CHAPTER V-Unexpected Help

- CHAPTER VI-New Hands on the Oars

- CHAPTER VII-Yankee from Kansas

- CHAPTER VIII-An Idea Moves West

- CHAPTER IX-New Horizons

- CHAPTER X-Henry Agard Wallace

- CHAPTER XI-New Victory at Tippecanoe

- CHAPTER XII-Successful Mission

- CHAPTER XIII-New Empire-in the North

- CHAPTER XIV-The Story of De Kalb

- CHAPTER XV-Fame Comes to El Paso

- CHAPTER XVI-Builders All

- CHAPTER XVII-New Temple on Old Foundations

- CHAPTER XVIII-Distinguished Service

- CHAPTER XIX-Just the Beginning