![]()

1

OUR APOSTLES, OURSELVES

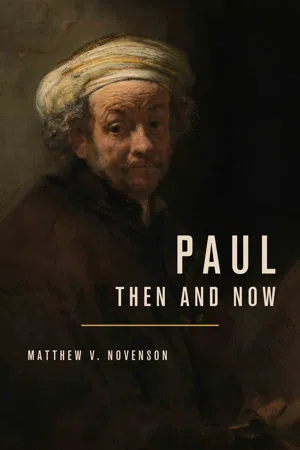

Rembrandt van Rijn, the seventeenth-century Dutch master, painted scores of self-portraits. But one of these self-portraits is not like the others. The face in the painting is clearly the artist’s own, but he is shown holding a book and a sword, the familiar distinguishing marks of medieval icons of Saint Paul. This is Rembrandt’s Zelfportret als de apostel Paulus, “Self-Portrait as the Apostle Paul,” of 1661. The figure we see is, at the same time, both the ancient apostle and the modern artist. As in visual art, so also in literature; that is the premise of this book. A great deal of modern interpretation of the Pauline letters consists of the interpreter making Paul speak for him (or her, but usually him). Our apostles, ourselves.

The roots of this fascinating reading strategy go back to antiquity. A letter ostensibly from Seneca to Paul preserved in the ancient Correspondence of Paul and Seneca reads:

When we had read your book, that is to say, one of the many letters of admirable exhortation to an upright life which you have sent to some city or to the capital of a province, we were completely refreshed. These thoughts, I believe, were expressed not by you, but through you; though sometimes they were expressed both by you and through you; for they are so lofty and so brilliant with noble sentiments that in my opinion generations of men could hardly be enough to become established and perfected in them. (Correspondence of Paul and Seneca §1)

By the time the fourth-century pseudepigrapher wrote these lines in the voice of Seneca the Younger, some ten or twelve generations of readers of Paul, at least, had already come and gone. Three centuries separated the “then” of the apostle from the “now” of the pseudepigrapher. And yet, our author reckons that many more generations will still be needed to plumb the depths of the letters—and here we are, in the 2020s CE, I writing a book on the letters of Paul, and you reading it. Equally interesting is our author’s notion that the words of Paul are, in a sense, not really words of Paul. They are, he believes, words of the divine muse that speaks through Paul. But if hermeneutical ventriloquism can turn Paul’s words into God’s words, it can also turn Paul’s words into the words of Paul’s later interpreters. In many but not all cases, these two phenomena are directly related: the interpreter, taking Paul’s words to be God’s words, uses Paul’s words to express what he or she, often on other grounds, believes to be divine truth.

Indeed, an enormous amount of the history of interpretation of Paul—like the history of interpretation of other parts of the Bible, but more so—consists of this very thing: the use of Paul’s words to make one’s own theological point. Ancient pseudepigraphers (like the author of the Correspondence of Paul and Seneca) made Paul speak for them by putting new words in his mouth. But the more usual way of making Paul speak for oneself, from antiquity down to the present, is simply to make the canonical words of Paul mean new things. The enormous grab bag of reading strategies traditionally called “historical criticism” remains useful today just to the extent that it helps us to keep that fact before our eyes and helps us to remember that an ancient author’s words did not always mean what they eventually came to mean.

With some biblical texts, modern critics have a relatively easy time remembering this; with other texts, much less so. When one reads Song of Songs as an allegory of Christ and the church, one knows without having to think too hard about it that to do so is to make a secondary (or tertiary, or quaternary) interpretive move. The many florid mentions of necks and breasts and gardens remind even the most pious reader that this poem was originally about, well, something else. But when one reads Paul’s Letter to the Galatians, one can easily trick oneself into thinking that the text is not about something strange and ancient, but about one’s own present-day theological concerns, whatever they may be. As Robert Morgan writes about Protestant interpreters in particular, “The field of Pauline interpretation … is where Protestant theologians since Luther have generally heard the gospel ‘clearest of all.’ This is, therefore, the point at which their interpretation of the tradition and their own theology are most likely to coincide. In saying what Christianity was for Paul, they are often saying what it is for themselves.” This is what I mean by hermeneutical ventriloquism. Morgan’s perceptive observation is especially true of Protestants (of which tribe—full disclosure—the present writer is a member), but not only of Protestants. Other denominations of Christians, not to mention non-Christian readers of various stripes, have likewise found Paul’s words useful for making their own points. My aim in saying this is not to throw stones at anyone for doing so. They are within their rights to use Paul’s words in this way. And even if they were not, it would doubtless carry on happening anyway. But in such a situation as this, it is not unreasonable to pursue greater clarity about what kind of reading, exactly, any particular reader is offering.

As I point out in the following chapters (especially chapters 2 and 11), recent interpretation of Paul has witnessed quite a lot of noisy insistence that people who do not read the letters in way x or y are doomed to get Paul wrong. In contrast to all that, I would like to rise in defense of (what Jeffrey Stout calls) the relativity of interpretation: the recognition that what counts as a good interpretation of the letters depends entirely on the questions and interests one brings, and that there are a great many worthwhile questions and interests one might bring (though there are also some bad questions and some blameworthy interests). Depending on the particular questions and interests at hand, very different reading strategies might be called for. Thus rightly Stout: “We might need many different complete interpretations of a given text to do all the explaining we want to do. This should encourage openness to the possibility that interpretations phrased in terms of Hirschian authorial intentions, Gadamerian talk of effective history, reception-theory à la Jauss, reader-response theory à la Iser, and the rest can sometimes usefully be seen as belonging to compatible explanatory projects geared to resolving different puzzles.” Indeed, Stout himself adduces the letters of Paul as an example in this connection. He writes:

An apostle of a religious movement writes a letter that is later canonized. You may be interested in constructing a picture that explains what the apostle was up to. If so, you will map the letter onto your language accordingly. But you may be interested instead in the letter as a scriptural book, in the relations its words and sentences take on in its canonical setting, and in its use as a normative document some centuries after it was authored. In that case, you will probably want an interpretation you can ascribe to the community for which the letter functions as scripture, thereby helping explain the community’s behaviour under circumstances unlike the author’s own.

In the present volume, I am for the most part “interested in constructing a picture that explains what the apostle was up to,” to use Stout’s idiom. That is to say, I come with a primary interest in the original historical situation of the letters and, consequently, questions framed in such a way as to illuminate that situation. These essays are, in other words, mostly historical-critical studies of the Pauline letters (focused on the first-century “then,” not the twenty-first-century “now”), although at many points throughout I also take up other, different readings of the same texts. I do so because I think that, in many cases, we can best clarify our own questions and interests by contrasting them with adjacent ones, by being as precise as possible about what we are and are not asking or claiming. This is all the more urgent with the letters of Paul because of their outsize influence in subsequent tradition. Once more Stout: “Philosophical and literary texts often enter the humanistic canon because they provide uniquely valuable occasions for normative reflection. We lavish great interpretive care upon them, but not always in order to ‘get them right.’ Getting them right sometimes ceases to matter. We sometimes want our interpretations to teach us something new, not so much about the text itself, its author, or its effective history as about ourselves, our forms of life, our problems.” As with the humanistic canon, so with the Christian canon. We might, and people very often do, read the letters of Paul in order to learn not about the letters themselves but about our own form of life. But that is a very different undertaking from reading the letters in order to learn about the past, which is the burden of the present volume. And we do both jobs better if we do not confuse the one with the other.

A few years ago, I wrote that, with her book Paul: The Pagans’ Apostle, Paula Fredriksen manages to “make Paul weird again.” (That essay of mine is now chapter 10 of the present volume.) The reason why that is such an important achievement is that Paul has come to seem so very not-weird, so normal, through long centuries of Christian use. We have made Paul’s words our own so many times over, in so many contexts, that we have come to view him simply as one of us. But he is not one of us. He is as strange and ancient as Boudica, or Honi the Circle-Drawer, or Peregrinus Proteus. The essays in the present volume try to read Paul as strange and ancient, to do what C. M. Chin calls “weird history” as opposed to “normalizing history.” Chin explains:

The historical project of making people from past worlds like us is an empathetic project, and it does useful work in many contexts, such as when we argue for the continued relevance of ancient history to the contemporary world. I would like to suggest, though, that the empathetic project of history, especially premodern history, is better served by a kind of imaginative stubbornness, a determination to remember that people living in past worlds were not always very much like us, but that we should pay attention to them anyway. And this much harder project of empathy is what I think focusing on weirdness allows us to undertake.

Just so. Paul was not always very much like us, but we should pay attention to him anyway. That is my watchword in the present volume. Of course, differently from most of the premodern past about which Chin writes here, the letters of Paul come down to us as part of Christian scripture, which adds another layer of complexity to the matter (to indulge in understatement). For of course, one very common approach to biblical texts is deliberately to read them as speaking to the present, not the past. But even with biblical texts—and even among religious readers, I would argue—a version of Chin’s rule really should stand. Recognizing that Paul belongs to the past forces us modern readers to take moral responsibility for our interpretations, which is all the more urgent for religious readers of the Bible. Contrary to a popular figure of speech, it is not the case that Paul (or Moses, or Jesus, etc.) speaks, and we just listen. No, we read Paul (or Moses, or Jesus, etc.) and generate our interpretations, for which we then stand responsible. Chin, again, puts the point eloquently:

The reason that hindering our ability to draw such historical analogies is morally important is that historical analogy is not a useful substitute for direct moral reasoning. Without recourse to such analogies, we are forced into the often uncomfortable position of asking ourselves directly, is what I am doing right now, in this moment, the right thing? The weirdness of the past gives us fewer places to hide in the present…. Domesticating the past is a disservice to that past in a factual sense, but it is also a disservice to ourselves in an aesthetic and moral sense. The project of learning to see and write weird history is a harder empathetic task than writing normalizing history.

“The weirdness of the past gives us fewer places to hide in the present.” As regards the letters of Paul, the lesson here is that later readers ought to own the uses to which they put Paul’s words. The buck stops with them, with us. Neither Augustine’s “Sin came into the world through one person,” nor Martin Luther’s “righteousness from faith,” nor Robert Louis Dabney’s “The one called as a slave is the Lord’s freedperson” is identical to what Paul meant by those words. Both Paul’s and Augustine’s views are “weird” (in Chin’s sense), but the one is not the other. If we mind the gap between Paul and Augustine, and the gap between Augustine and us, and the gap between Paul and us, and so on, then we stand to understand all parties better. This example reminds us that there are not just—as the hermeneutical slogan has it—two horizons: ancient text and modern reader, then and now. There are myriad horizons (“thens”) in between, all pressing, powerfully but often silently, upon the modern reader of Paul. Marcion, Valentinus, Tertullian, Augu...