![]() SECTION TWO

SECTION TWO

WORK AS A COMPONENT OF STUDENT IDENTITY ![]()

2

ADULT WORKERS AS UNDERGRADUATE STUDENTS

Significant Challenges for Higher Education Policy and Practice

Carol Kasworm

As noted in chapter 1, in American higher education, work is more common among undergraduate students who are adult learners—individuals who are 25 years of age and older—than among traditional-age students. Working adult students are a unique segment within the total undergraduate population, representing approximately 80% of all adult undergraduate students and approximately 60% of all working undergraduates (O’Donnell, 2006; National Center for Education Statistics [NCES], 2008).

Unlike younger undergraduates, adult students come to college at different stages in their lives and often are driven by broader forces such as global workforce turbulence, commitment to family survival and betterment, interest in developing personal competence, and the impact of a shrinking community economy (Kasworm, 2008). Their participation as part-time students and full-time workers, as well as their more complex and varied goals for engagement in higher education, challenge past paradigms of undergraduate participation.

Much past literature on collegiate participation suggests a pipeline metaphor for undergraduate education—a bridge between youth and future adulthood and career. However, as Ziskin and colleagues (chapter 4 in this volume) also note, these full-time working adults present more varied collegiate participation patterns. In addition, younger working adults who are part-time and/or intermittent students are increasingly represented.

Thus, as we consider adult workers and a growing subgroup of younger workers in higher education, we need to rethink the nature of participation. One alternative is the paradigmatic image of an airport. This notion of an airport reflects a different framework defining the new realities of undergraduate access and participation. This image of an airport suggests that higher education is a “terminal” with individuals entering and exiting to accomplish specific educational goals on a discontinuous basis. Thus, rather than a pipeline between youth and adulthood with a commitment to continuous involvement, higher education participation is now represented in segments across the life span of adulthood and based in learner-specific goals and needs. This paradigm of the airport also reflects the growing need for adult access to new advanced knowledge. Undergraduate education must also support the continuously evolving global knowledge economy and related adult learner needs for updated and often redefined knowledge and skills. As we consider participation of adult workers who are undergraduate students, we need to recognize that undergraduate education that is contiguous and complementary to the complex world of adult-life commitments is more appropriate than a pipeline solely focused on full-time, young student participation.

With a focus on the adult worker who is a student, this chapter presents four perspectives for future policy, research, and practice. The chapter first discusses the importance of a higher education system that is responsive to the global knowledge economy for a competitive knowledgeable workforce. The chapter then examines the demographic landscape of adult workers in undergraduate education. Given the lack of available conceptual models to guide theory, practice, and policy regarding adult workers as students, the third section presents a new framework, the Adult Undergraduate Student Identity (AUSI) model, which identifies the key psychological and cultural factors shaping the beliefs and actions of adults who are engaged in undergraduate studies. The chapter concludes by highlighting contemporary designs, delivery systems, and ideologies that have supported past access and successful engagement of working adults as students.

Global Knowledge Economy and the Adult Working Student

Over the past four decades, American employers have increasingly expected employees to have more advanced levels of knowledge and skills. Higher education and business leaders suggest that undergraduate education should provide cutting-edge knowledge, as well as cognitive complexity, instruction in abstract reasoning and decision making, opportunities for creativity, and innovation (Jones, 2002; Paul & Beach, 1995). Although directed to all participants in undergraduate education, this expectation has had a profound impact on adults who are currently in the workforce, especially those with more limited education, knowledge, and skills. Adult workers age 25 and older who lack an undergraduate credential often face an unstable work life and experience job changes, job dislocation, and difficulties in job advancement more often than younger students do (Kasworm & Blowers, 1994). In a study of adult undergraduates, Kasworm and Blowers found that approximately two thirds (approximately 60 of the 90 randomly selected adults in undergraduate studies) had faced major job or career issues because of the lack of an undergraduate credential, with 13%, or 12 of the 90 adults, experiencing job dislocation.

Recent unemployment figures have become a prominent catalyst for targeting national and state higher education agendas toward energizing policy and programs for workforce development and responsive undergraduate education. In this era of global economic transformation, an undergraduate education has become a desired component of educational and workforce policies designed to support a competitive economy and the viability of our communities and nation. As suggested by the World Bank, “Lifelong learning is crucial to preparing workers to compete in the global economy. But it is important for other reasons as well. By improving people’s ability to function as members of their communities, education and training increase social cohesion, reduce crime, and improve income distribution” (n.d.).

This significant role of higher education in the knowledge economy is not just an American phenomenon. During the last two decades, a global imperative has emerged of the importance to the world economy of lifelong learning for workers. International policy and scholarly forums, including the United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), OECD, European Union, and Pan-Asian forums such as the World Conference on Lifelong Learning in Korea, have noted the importance of lifelong learning as a policy tool for future higher education endeavors linked to economic vitality (Kasworm, 2007b).

Higher education has become interwoven with the broader lifelong-learning agenda. Higher education’s role in lifelong learning is evidenced in part by the crumbling boundaries between the academic and business worlds, as represented by corporate colleges and contract on-site degree programs, as well as customized workforce training to attract industries to a particular locale. Higher education has experienced the merging of continuing education (e.g., evening colleges and summer school) with the growing use of distance outreach education, and evolving undergraduate on-campus education. In higher education, the traditional distinctions among teaching, research, and outreach/extension have blurred, resulting in adoption of a variety of change strategies, partnerships and stakeholder engagements, and creative financing intertwined with the broader agendas of lifelong learning (Aspin, Chapman, Hatton, & Sawano, 2001; Kasworm, 2007b). Higher education has become an institution for lifelong learning directed to the diverse and complex population of adults in the workforce and in the global society, as well as serving the historic mission of preparing youth for future careers and world citizenship.

Within this mission of lifelong learning, societal policymakers also perceive higher education as vital for aiding undereducated and dislocated workers. There has been significant loss of human capital because of the millions of undergraduate dropouts and stop-outs who are now adult workers with limited advanced knowledge and skills and who have had difficulties in returning to undergraduate studies. These individuals represent approximately 32.3 million adults (Jones & Kelly, 2007), almost twice the current total U.S. undergraduate enrollment. In addition, there are untold numbers of other individuals who have previously completed a degree, but who do not view this degree as viable preparation for a career (Kohl & LaPidus, 2000). Many of these individuals seek out undergraduate studies as postbaccalaureate students to obtain credentials required to enter a preferred new career. Postbaccalaureate students were estimated to number approximately 1.5 million adults in 1999 (Kohl & LaPidus, 2000).

As suggested in a National Center for Higher Education Management Systems (NCHEMS) report (Jones et al., 2007), adult learners are the key force for the future of higher education and a competitive national economy. Reports by NCHEMS and the U.S. Secretary of Education’s Commission on the Future of Higher Education (Stokes, 2006) suggest that a key challenge for responsive higher education is serving the adult worker. At the heart of this challenge is reconfiguring the policy and practice of undergraduate education to encourage and support adult learners who have complex life roles of worker, family member, spouse, and community leader alongside their student role.

Demographics of Adult Workers Who Are Undergraduate Students

To understand the complex worlds of adult workers who are undergraduate students, we first need to examine the broader landscape of adult participation in lifelong learning. In 2005, 54% of U.S. adults participated in formal educational activities, predominantly through credit or noncredit higher education, corporate universities, or related formal classroom and online training (NCES, 2008). This percentage represents a sizeable increase over time because earlier data show that 44% of U.S. adults (60 million) reported formal educational involvement in 2001. In both reports, the predominant involvement of adults was in work-related educational efforts. In 2005, more than 12 million adults age 25 and older participated specifically in credential or degree-granting programs in colleges and universities. An estimated 80% to 95% of these adults focused on achieving work-related educational goals (O’Donnell, 2006; NCES, 2008; Stokes, 2006).

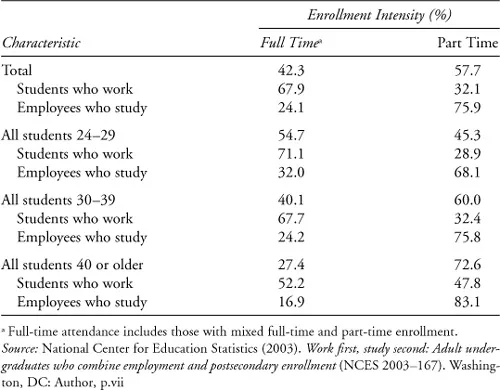

Although adult workers who are also undergraduate students are a difficult population to track, data from the National Center for Educational Statistics provide selective understandings of the characteristics of undergraduates who work. In 1989–1990, 23% of young undergraduates and 46% of older undergraduates worked 40 or more hours a week. A more recent National Center for Education Statistics study (NCES, 2003), Work first, study second: Adults who combine employment and postsecondary enrollment, compared adults age 24 and older who viewed themselves as primarily employees who also study with those who view themselves as primarily students who work to pay for study. As noted in Table 1, a fundamental difference between these two groups is how students combine work and attendance. Most employees who study are enrolled part time (76%), while most students who work are enrolled full time (68%).

TABLE 1

Distribution of Students Who Work and Employees Who Study by Age and Enrollment Intensity: 2003–2004

Employees who study are engaged in higher education to maintain or gain knowledge and skills and related certification to support their career advancement. Undergraduate credentials may help these individuals receive a raise or promotion and/or attain a new job or career with a new employer, as well as meet employer requirements to participate in advanced education (O’Donnell, 2006).

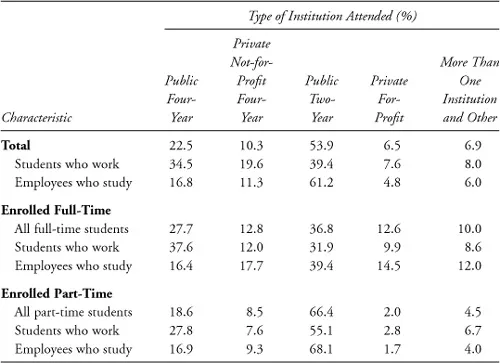

TABLE 2

Distribution of Students by Type of Institution Attended, Student/Employee Role, and Attendance Intensity: 1999–2000

Note: Full-time attendance includes those who also had mixed full-time and part-time enrollment. Rows may not total 100% because of rounding. Total and “ALL” rows for each subgroup also include students who did not work while enrolled.

Source: National Center for Education Statistics (2003). Work first, study second: Adult undergraduates who combine employment and postsecondary enrollment (NCES 2003–167). Washington, DC: Author, p. iv

Adult workers who are students do not participate in equal numbers in the varied levels and types of higher education institutions. As noted in Table 2, working adults (i.e., employees who study) are more likely to participate in two-year than four-year colleges. This NCES (2003) report also suggests that differences in participation rates across different types of institutions may reflect differences in institutional mission for serving working students or differences in institutional orientation toward serving regional business and industry through offering educational programs targeted to workforce needs. The report notes that the lower percentages of workers as students in many four-year colleges and universities may reflect institutional requirements such as for full-time attendance. In addition, a number of these institutions schedule most classes during the day, a problematic design for full-time adult workers. Thus, four-year institutions often report lower enrollments of adult students, suggesting campus environments that are not accessible to adult students and that do not provide instruction and services that are responsive to adult workers.

These varied reports also show that workers who are also students have a number of characteristics that place them at risk for failing to complete college. These students take longer to gain a degree than other students. Adult working students are also more likely to have dependents as well as a spouse. Financial support for college studies is more problematic for them. Moreover, these individuals are more likely to be first-generation college students (NCES, 1995, 2003; O’Donnell, 2006). Reflecting these different characteristics and participation patterns, the following section presents an alternative framework for effectively serving this important undergraduate population.

Creating Responsive Undergraduate Education for Adult Workers Who Are Students: The Adult Undergraduate Student Identity (AUSI) Model

I propose the following model as an alternative perspective for responding to the unique needs of adult workers who are also undergraduate students. This proposed Adult Undergraduate Student Identity (AUSI) model offers a framework for identifying key factors that influence adult workers’ participation in undergraduate education. Developed from a number of my prior research investigations, the AUSI model identifies key factors of adult identity that influence adult worker participation. This model suggests that adult workers who are undergraduates differ from younger adult undergraduates in the complexity of their age-related life roles as well as in their beliefs and life realities in regard to involvement in undergraduate education. This model presents a conceptual framework for delineating the complex and evolving world of decisions and actions of adult students in undergraduate education (Kasworm, 2007a; Kasworm, Polson, & Fishback, 2002).

Understanding adult workers who are students requires understanding their complex and competing adult identities—identities that include worker and student as well as others. As noted by Gee (2001), identity is “being recognized as a certain ‘kind of person,’ in a given context … all people have multiple identities connected not to their ‘internal states’ but to their performances in society” (p. 99). Individuals assume different identities in different social contexts and encounters. As individuals participate in knowledge construction and meaning making across their adult life roles, these varied identities and related efforts to assume agency influence the nature of their participation in higher education (Kasworm, 2003).

As noted in earlier research regarding adult students’ sense of place, identity, and agency, these individuals place primary individual identity and energy in their significant worlds of work, family, and community responsibilities (Kasworm & Blowers, 1994; Kasworm et al., 2002). Collegiate participation for most adult students is important, but often it is one of four to six primary competing life investments—investments that are reflective of ego identity, life values, and resources. Although “time investment and involvement” may be a central definer for undergraduate student success and satisfaction, the AUSI framework and supporting research suggest that adult students participate in undergraduate studies through “identity anchor” commitments vis-à-vis their other life worlds. These committed worlds of self and action influence adult students’ collegiate participation, engagement in learning, and sense of place within a student identity.

Overview of the Adult Undergraduate Student Identity Model

As mentioned, I developed the Adult Undergraduate Student Identity (AUSI) model based on my prior research conducted across a variety of collegiate institutions and adult students. The study includes interviews of 90 adult undergraduate students (age 30 years and older) who were purposefully selected to reflect the following characteristics: (a) had an interruption in their forma...