![]() PART I

PART I

AN INTRODUCTION TO RUBRICS![]()

1

WHAT IS A RUBRIC?

\Ru”bric\, n. [OE. rubriche, OF. rubriche, F. rubrique (cf. it. rubrica), fr. L. rubrica red earth for coloring, red chalk, the title of a law (because written in red), fr. ruber red. See red.] That part of any work in the early manuscripts and typography which was colored red, to distinguish it from other portions. Hence, specifically: (a) A titlepage, or part of it, especially that giving the date and place of printing; also, the initial letters, etc., when printed in red. (b) (Law books) The title of a statute;—so called as being anciently written in red letters.—Bell. (c) (Liturgies) The directions and rules for the conduct of service, formerly written or printed in red; hence, also, an ecclesiastical or episcopal injunction;—usually in the plural.

—Webster’s Unabridged Dictionary, 1913

Rubric: n. 1: an authoritative rule 2: an explanation or definition of an obscure word in a text [syn: gloss] 3: a heading that is printed in red or in a special type v : adorn with ruby red color.

—WordNet, 1997

Today, a rubric retains its connection to authoritative rule and particularly to “redness.” In fact, professors like us who use rubrics often consider them the most effective grading devices since the invention of red ink.

At its most basic, a rubric is a scoring tool that lays out the specific expectations for an assignment. Rubrics divide an assignment into its component parts and provide a detailed description of what constitutes acceptable or unacceptable levels of performance for each of those parts. Rubrics can be used for grading a large variety of assignments and tasks: research papers, book critiques, discussion participation, laboratory reports, portfolios, group work, oral presentations, and more.

Dr. Dannelle Stevens and Dr. Antonia Levi teach at Portland State University in the Graduate School of Education and the University Studies Program, respectively. Rubrics are used quite extensively for grading at Portland State University, especially in the core University Studies program. One reason for this is that the University Studies Program uses rubrics annually to assess its experimental, interdisciplinary, yearlong Freshman Inquiry core. Because that assessment is carried out by, among others, the faculty who teach Freshman Inquiry, and because most faculty from all departments eventually do teach Freshman Inquiry, this means that the faculty at Portland State are given a chance to see close up what rubrics can do in terms of assessment. Many quickly see the benefits of using rubrics for their own forms of classroom assessment, including grading.

In this book, we will show you what a rubric is, why so many professors at Portland State University are so enthusiastic about rubrics, and how you can construct and use your own rubrics. Based on our own experiences and those of our colleagues, we will also show you how to share the construction or expand the use of rubrics to become an effective part of the teaching process. We will describe the various models of rubric construction and show how different professors have used rubrics in different ways in different classroom contexts and disciplines. All the rubrics used in this book derive from actual use in real classrooms.

Do You Need a Rubric?

How do you know if you need a rubric? One sure sign is if you check off more than three items from the following list:

You are getting carpal tunnel syndrome from writing the same comments on almost every student paper.

It’s 3

A.M. The stack of papers on your desk is fast approaching the ceiling. You’re already 4 weeks behind in your grading, and it’s clear that you won’t be finishing it tonight either.

Students often complain that they cannot read the notes you labored so long to produce.

You have graded all your papers and worry that the last ones were graded slightly differently from the first ones.

You want students to complete a complex assignment that integrates all the work over the term and are not sure how to communicate all the varied expectations easily and clearly.

You want students to develop the ability to reflect on ill-structured problems but you aren’t sure how to clearly communicate that to them.

You give a carefully planned assignment that you never used before and to your surprise, it takes the whole class period to explain it to students.

You give a long narrative description of the assignment in the syllabus, but the students continually ask two to three questions per class about your expectations.

You are spending long periods of time on the phone with the Writing Center or other tutorial services because the students you sent there are unable to explain the assignments or expectations clearly.

You work with your colleagues and collaborate on designing the same assignments for program courses, yet you wonder if your grading scales are different.

You’ve sometimes been disappointed by whole assignments because all or most of your class turned out to be unaware of academic expectations so basic that you neglected to mention them (e.g., the need for citations or page numbers).

You have worked very hard to explain the complex end-of-term paper, yet students are starting to regard you as an enemy out to trick them with incomprehensible assignments.

You’re starting to wonder if they’re right.

Rubrics set you on the path to addressing these concerns.

What Are the Parts of a Rubric?

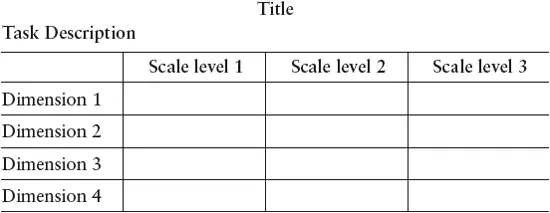

Rubrics are composed of four basic parts in which the professor sets out the parameters of the assignment. The parties and processes involved in making a rubric can and should vary tremendously, but the basic format remains the same. In its simplest form, the rubric includes a task description (the assignment), a scale of some sort (levels of achievement, possibly in the form of grades), the dimensions of the assignment (a breakdown of the skills/knowledge involved in the assignment), and descriptions of what constitutes each level of performance (specific feedback) all set out on a grid, as shown in Figure 1.1.

Figure 1.1 Basic rubric grid format.

We usually use a simple Microsoft Word table to create our grids using the “elegant” format found in the “auto format” section. Our sample grid shows three scales and four dimensions. This is the most common, but sometimes we use more. Rarely, however, do we go over our maximum of five scale levels and six to seven dimensions.

In this chapter, we will look at the four component parts of the rubric and, using an oral presentation assignment as an example, develop the previous grid part-by-part until it is a useful grading tool (a usable rubric) for the professor and a clear indication of expectations and actual performance for the student.

Part-by-Part Development of a Rubric

Part 1: Task Description

The task description is almost always originally framed by the instructor and involves a “performance” of some sort by the student. The task can take the form of a specific assignment, such as a paper, a poster, or a presentation. The task can also apply to overall behavior, such as participation, use of proper lab protocols, and behavioral expectations in the classroom.

We place the task description, usually cut and pasted from the syllabus, at the top of the grading rubric, partly to remind ourselves how the assignment was written as we grade, and to have a handy reference later on when we may decide to reuse the same rubric.

More important, however, we find that the task assignment grabs the students’ attention in a way nothing else can when placed at the top of what they know will be a grading tool. With the added reference to their grades, the task assignment and the rubric criteria become more immediate to students and are more carefully read. Students focus on grades. Sad, but true. We might as well take advantage of it to communicate our expectations as clearly as possible.

If the assignment is too long to be included in its entirety on the rubric, or if there is some other reason for not including it there, we put the title of the full assignment at the top of the rubric: for example, “Rubric for Oral Presentation.” This will at least remind the students that there is a full description elsewhere, and it will facilitate later reference and analysis for the professor. Sometimes we go further and add the words “see syllabus” or “see handout.” Another possibility is to put the larger task description along the side of the rubric. For reading and grading ease, rubrics should seldom, if ever, be more than one page long.

Most rubrics will contain both a descriptive title and a task description. Figure 1.2 illustrates Part 1 of our sample rubric with the title and task description highlighted.

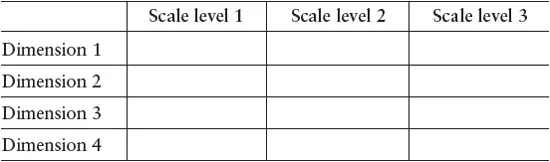

Part 2: Scale

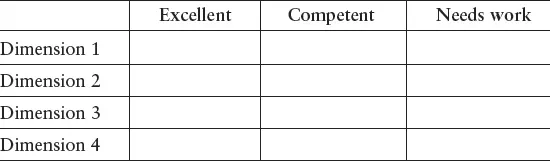

The scale describes how well or how poorly any given task has been performed and occupies yet another side of the grid to complete the rubric’s evaluative goal. Terms used to describe the level of performance should be tactful but clear. In the generic rubric, words such as mastery, partial mastery, progressing, and emerging provide a more positive, active verb description of what is expected next from the student and also mitigate the potential shock of low marks in the lowest levels of the scale. Some professors may prefer to use nonjudg-mental, noncompetitive language, such as “high level,” “middle level,” and “beginning level,” whereas others prefer numbers or even grades.

Changing Communities in Our City

Task Description: Each student will make a 5-minute presentation on the changes in one Portland community over the past thirty years. The student may focus the presentation in any way he or she wishes, but there needs to be a thesis of some sort, not just a chronological exposition. The presentation should include appropriate photographs, maps, graphs, and other visual aids for the audience.

Figure 1.2 Part 1: Task description.

Here are some commonly used labels compiled by Huba and Freed (2000, p. 180):

• Sophisticated, competent, partly competent, not yet competent (NSF Synthesis Engineering Education Coalition, 1997)

• Exemplary, proficient, marginal, unacceptable

• Advanced, intermediate high, intermediate, novice (American Council of Teachers of Foreign Languages, 1986, p. 278)

• distinguished, proficient, intermediate, novice (Gotcher, 1997)

• accomplished, average, developing, beginning (College of Education, 1997)

We almost always confine ourselves to three levels of performance when we first construct a rubric. After the rubric has been used on a real assignment, we often expand that to five. It is much easier to refine the descriptions of the assignment and create more levels after seeing what our students actually do.

Changing Communities in Our City

Task Description: Each student will make a 5-minute presentation on the changes in one Portland community over the past thirty years. The student may focus the presentation in any way he or she wishes, but there needs to be a thesis of some sort, not just a chronological exposition. The presentation should include appropriate photographs, maps, graphs, and other visual aids for the audience.

Figure 1.3 Part 2: Scale.

Figure 1.3 presents the Part 2 version of our rubric where the scale has been highlighted.

There is no set formula for the number of levels a rubric scale should have. Most professors prefer to clearly describe the performances at three or even five levels using a scale. But five levels is enough. The more levels there are, the more difficult it becomes to differentiate between them and to articulate precisely why one student’s work falls into the scale level it does. On the other hand, more specific levels make the task clearer for the student and they reduce the professor’s time needed to furnish detailed grading notes. Most professors consider three to be the optimum number of levels on a rubric scale.

If a professor chooses to describe only one level, the rubric is called a holistic rubric or a scoring guide rubric. It usually contains a description of the highest level of performance expected for each dimension, followed by room for scoring and describing in a “Comments” column just how far the student has come toward achieving or not achieving that level. Scoring guide rubrics, however, usually require considerable additional explanation in the form of written notes and so are more time-consuming than grading with a three-to-five-level rubric.

Part 3: Dimensions

The dimensions of a rubric lay out the parts of the task simply and completely. A rubric can also clarify for students how their task can be broken down into components and which of those components are most important. Is it the grammar? The analysis? The factual content? The research techniques? And how much weight is given to each of these aspects of the assignment? Although it is not necessary to weight the different dimensions differently, adding points or percentages to each dimension further emphasizes the relative importance of each aspect of the task.

Dimensions should actually represent the type of component skills students must combine in a successful scholarly work, such as the need for a firm grasp of content, technique, citation, examples, analysis, and a use ...