![]() PART ONE

PART ONE

THEORY, ORGANIZATIONAL LEARNING, AND TOOLS AND PRACTICES OF THE EQUITY SCORECARD![]()

1

THE EQUITY SCORECARD

Theory of Change

Estela Mara Bensimon

In the Equity Scorecard process, student success in college is framed as an institutional responsibility that requires race-conscious expertise. The centrality of race-conscious practitioner expertise distinguishes the Equity Scorecard process from the more familiar models of student success. Prevailing models of student success are based on sociopsychological behavioral theories of student development, integration, and engagement. Typically academic success is described and assessed as behaviors, attitudes, and aspirations that represent how college students, ideally, ought to be. The normative model of academic success focuses on the student’s self-motivation and the amount of effort he or she willingly invests into the academic activities that signify he or she is taking on the identity of “college student.” The normative model of academic success is exemplified by Vincent Tinto’s (1987) theory of academic and social integration, Alexander Astin’s theory of involvement, and George Kuh’s (2003) model of student engagement. Although there is no lack of evidence that these models capture what it takes to be academically successful in our colleges and universities, there is also plenty of evidence showing that very large numbers of students do not have access to the social networks that can help them develop the knowledge, practices, attitudes, and aspirations associated with the ideal college student.

Practitioners and scholars typically respond to evidence of low rates of college completion by asking questions that focus attention on the student: Are these students academically integrated? Do these students exhibit desired behavioral patterns? Do these students exert effort? How does the effort of these students compare with the effort of such-and-such group? How do the aspirations of high-performing students compare with those of low-performers? Are they engaged? Are they involved? Are they motivated? Are they prepared?

A premise of the Equity Scorecard process is that questions like these reflect a normative model of academic success. That is, academic success is associated with the experiences, behaviors, and values of the full-time, traditional college-age student. When we come across students who are not engaged or involved, who don’t take advantage of support resources, or who rarely ask questions or seek help, we judge them as deficient and in need of compensatory interventions. These students often acquire the “at-risk” label.

The purpose of this chapter is to introduce a theory of student success that focuses on the knowledge and behaviors of practitioners and institutions, rather than on the knowledge and behaviors of students. Instead of speaking about the racial achievement gap, we focus on the knowledge and cultural gap that undercuts practitioners’ capacity to be responsive to the students they get, rather than the ones they might wish for.

The chapter introduces the concept of funds of knowledge for race-conscious expertise, followed by a discussion of the four theoretical strands: sociocultural theories of learning, organizational learning, practice theory, and critical theories of race that represent the principles of change underlying the Equity Scorecard process. The chapter concludes with the attributes of equity-minded individuals.

Funds of Knowledge for Race-Conscious Expertise

In this section we discuss the meaning of funds of knowledge, how they develop, why the prevailing funds of knowledge that practitioners draw on are inadequate to undo racial patterns of inequity, and how practitioners can develop funds of knowledge that increase their expertise to make equity possible.

The terms funds of knowledge (González, Moll, & Amanti, 2005; Moll, Amanti, Neff, & Gonzalez, 1992), background knowledge (Polkinghorne, 2004), tacit knowledge, implicit theories, cognitive frames (Bensimon, 2005), and cultural frameworks, among many others, have been used by social scientists to describe historically developed and accumulated strategies (e.g., skills, abilities, ideas, practices) or bodies of knowledge that practitioners draw on, mostly unconsciously, in their everyday actions. They draw on these funds of knowledge as they decide what to pay attention to, what decisions to make, or how to respond to particular situations (Polkinghorne, 2004). A premise of the Equity Scorecard process is that practitioners can make a marked difference in the educational outcomes of minoritized1 (Gillborn, 2005) students if they recognize that their practices are not working and participate in designed situated learning opportunities to develop the funds of knowledge necessary for equity-minded practice (Bensimon, Rueda, Dowd, & Harris, 2007).

How do we know that practitioners’ funds of knowledge are inadequate for the task of improving the academic outcomes of minoritized populations? Through our work with the many campuses implementing the Center for Urban Education’s (CUE’s) Equity Model, we have documented the conversations of practitioners as they attempt to make sense of racial patterns of inequity revealed by their own institutional data. The Equity Scorecard process, through its various data tools and data practices, enables practitioners to notice racial disparities in successful completion of remedial2 courses in English and mathematics; persistence in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) majors; transfer to four-year colleges; graduation with honors; and many other fine-grained measures that signify the completion of critical milestones as well as participation in academic opportunities (e.g., studying abroad, doing research with a faculty member, having an internship in a Fortune 500 company, transferring to a highly selective college) that enhance students’ likelihood of accessing valued experiences, resources, and social networks.

Our analyses of practitioners’ talk consistently show that the prevailing funds of knowledge informing their interpretations of student outcomes reflect widely accepted beliefs about student success. These beliefs are mostly derived from psychological theories of motivation, self-efficacy, and self-regulation, as well as sociological theories of cultural integration. In essence, practitioners have learned to associate academic success with individual characteristics and attributes that signify the motivated, self-regulating, and academically and socially engaged archetype college student. For sure, it is hard to dispute practitioners’ desire for college students who are responsible; persist from semester to semester; and graduate, if not in four years, within six. But the reality is that a great many students, particularly those who are first-generation, low-income, immigrant, or from marginalized racial and ethnic groups have been disadvantaged by highly segregated high schools that lacked the resources to prepare them, academically and culturally, for college. Upon entering college these students are further disadvantaged by a college culture that expects them to know the rules and behaviors of academic success: seeking help when in academic trouble, visiting faculty members during office hours, knowing how to study, and having goals and being committed to them.

These students are not an exception. In many colleges, particularly community colleges and four-year colleges with open admissions policies, they are modal students. Viewed through the normative lens of academic success, these students fall so short of the image we have of academic-ready college students that they have become known as at-risk. Herein lies a major obstacle to the agenda of equity in educational outcomes for minoritized students: The funds of knowledge that lead practitioners to expect self-directed students, and to label those who fall short of the ideal at-risk, reinforce a logic of student success that is detrimental to an equity change agenda.

The logic underlying the notion of at-risk students goes something like this: “If students are not doing well it must be because they are not exerting the effort/seeking help/motivated; or because they are working too many hours/unprepared for college/disengaged.” Framing the problem in this manner is defeatist in that patterns of racial inequity seem inevitable and self-fulfilling. This leaves little hope for practitioner agency. It is also unproductive because a focus on the deficits of students discourages practitioners’ deeper reflection about their failure to understand the structural production of inequality or the need for institutional responsibility—in practices and ethos—for producing racial equity in educational outcomes.

To bring about institutional transformation for equity and student success, practitioners, including institutional leaders, have to develop funds of knowledge for equity-minded expertise. We pause here to provide an example that contextualizes the meaning of deficit and equity-minded funds of knowledge through an actual conversation among members of a campus team that participated in one of CUE’s early field tests3 of the “Equity Scorecard” (at the time called “Diversity Scorecard”). This excerpt was adapted from “Learning Equity-Mindedness: Equality in Educational Outcomes” (Bensimon, 2006) to illustrate funds of knowledge that represent a deficit perspective of student success. Throughout the rest of the chapter we will refer to it to show how the Equity Scorecard process attempts to remediate this perspective.

Campuses that adopt the Equity Scorecard process create teams of practitioners based on specific criteria: knowledge; leadership attributes; and forms of involvement in decision making, academic governance, and administrative structures. Institutional researchers are required to be members of the teams because the Equity Scorecard process’s initial phases involve the review of numerical data as a means of raising awareness of inequality at various stages of educational progress and success.

The team portrayed in the following excerpt had been meeting for several months to create indicators for its campus’s Equity Scorecard. One of the perspectives of the Scorecard is “excellence” and teams typically examine indicators that, as mentioned previously, illustrate experiences and relationships that give students access to scarce resources that create advantage for a small number of beneficiaries (e.g., honors programs).

Among community college teams a common measure of equity within the “excellence” perspective of the Scorecard is the proportion of students, by race and ethnicity, who transfer to selective colleges. We encourage community college teams to examine transfer patterns to highly selective institutions, particularly the flagship campuses of their public university system because there is a tendency to ignore racial and ethnic access to high-resourced and elite institutions. For example, if the community college portrayed in the excerpt was located in Texas, then the team would look at transfer to UT–Austin or Texas A&M at College Station; if it was located in Wisconsin, then transfer patterns to UW Madison would be the focus of the analysis. In California, transfer into UC–Los Angeles and UC–Berkeley would constitute important metrics of equity.

The Funds of Knowledge Evident in Team Members’ Data Interpretations

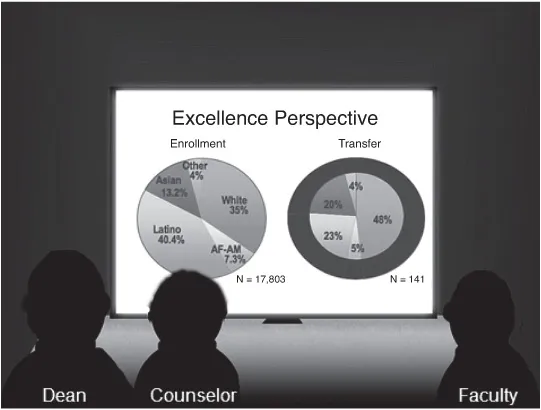

The following excerpt from a conversation among three members of a community college Equity Scorecard evidence team4 was prompted by data on transfer patterns to the state’s highly selective flagship university, which is located about ten miles from the college. To make it easier for the team members to notice the patterns of inequity, the institutional researcher created two pie charts (see Figure 1.1). The pie chart on the left shows that among the almost 18,000 students enrolled in the college, Latinas and Latinos are the largest group, constituting just over 40 percent of the total head count, followed by Whites (35 percent), Asian Americans (13 percent), African Americans (7 percent), and American Indians (4 percent). The pie chart on the right shows that on the particular year being examined, 141 students transferred successfully to the highly selective public university. As can be seen immediately, Latinos’ and Latinas’ share of the students who transferred to the flagship university is 23 percent, which is considerably lower than their 40 percent share of the total enrollment. In the case of Latinas and Latinos, to have equity in transfer to the flagship university they would need to increase their share from 23 percent to 40 percent. The pie chart also shows that while White students represent 35 percent of the total student population, their share of the transfer population is 48 percent.

Let’s see how three of the team members attempt to create meaning of the equity gaps between enrollment and transfer to the highly selective university campus. As you read the excerpt it is important to concentrate on the language used and reflect on the ways in which unequal outcomes are attributed to students’ characteristics, making them the authors of their own inequities.

Dean: More Black and Latino students may transfer to the local four-year college than to the state’s leading university because the state college is closer to home.

Counselor: This may be an issue for Latino students because of the pressure from family to remain close to home.

FIGURE 1.15 Members of a community college evidence team comparing the shares of total enrollment and transfers to a selective university by race and ethnicity.

Faculty: It may also be related to financial issues. Many students do not know about financial aid options. They also tend to manage money poorly.

Counselor: Many students don’t take advantage of the tutoring and counseling services we offer because they are embarrassed to use them or don’t see their relevance to educational success.

Faculty: Or they may not value education intrinsically but see it as a ticket to a well-paying job. Many of our Latino and African American students need remediation due to inadequate academic preparation, but they are not willing to put in the work necessary to be able to transfer. Some of them may need two or three years of remediation even to begin taking courses that are transferable, and this discourages many students.

Based on how these individuals respond to the data, what are they saying and what can be inferred about the funds of knowledge implicit in their interpretations about unequal patterns of outcomes? This is how we read it:

1. The individuals construct a narrative about the pie charts in such a way that inequity, instead of being interpreted as a racialized outcome is rationalized as a cultural predisposition of Latino and Black students to “stay close to home.”

2. The assumption is made that the students may be low income and need financial aid to be able to transfer to the more selective college, but they are not smart enough to take advantage of financial aid opportunities, nor do they have the competence to manage their finances responsibly.

3. The assumption is made that students lack the academic qualifications; therefore, they have to enroll in remedial education courses, taking them longer to get to the college-level courses that will eventually make them eligible for transfer. It is assumed that the students do not help themselves because they don’t take advantage of the college’s academic support services. Why not? Because, it is assumed, that they are embarrassed to admit they need help or they don’t have the motivation; or because they lack the stick-to-itness needed to get through the long sequence of remedial education courses.

4. In addition, it is assumed, these students may not have the cultural or social class predisposition to appreciate education for its own sake. The assumption is that they are more motivated by occupational opportunities than by a general and liberal arts education.

The explanations given by the participants foreground student deficits and take the focus away from the pattern of intrainstitutional racial inequity that is revealed by the transfer patterns in the pie chart. The conversation among the dean, counselor, and instructor bring to mind the “color-mute” (Pollock, 2004) euphemisms that are used in education—“at-risk,” “disadvantaged,” “underprepared”—to attribute disparities to race and culture without appearing to do so.

The dialogue creates the distinct impression that what we interpret as an instance of inequity in transfer patterns these practitioners view as the domino effect of cumulative disadvantages inherent in the students’ cultural and social characteristics, which are manifested in lack of self-efficacy, lack of effort, lack of ambition, and avoidance of help-seeking due to hyper self-consciousness. The influence of normative concepts of student success (e.g., commitment, effort, motivation, and integration) are discernable in the team members’ attribution of small transfer numbers among Latinas and Latinos to inadequate values, not having the right attitude, and not engaging in desirable behavioral patterns.

Although it is possible that the practitioners in the illustration may not be familiar with the scholarly literature on college student development and success, it is highly likely that they have been exposed to key concepts such as engagement, involvement, effort, and integration in conference ...