![]()

1

REVOLUTIONIZING LEADERSHIP DEVELOPMENT

Lessons From Research and Theory

Adrianna Kezar and Rozana Carducci

Today’s leadership development coordinator: I think it was much easier when I could isolate the few characteristics that people could use in all situations to be successful leaders.

Tomorrow’s leadership development coordinator: I like demonstrating how leadership is affected by context, culture, and situational elements. It really feels authentic to me to help people carefully observe and interpret their environment and the people within it to be successful leaders.

Today’s leadership development coordinator: It helps when you can clearly identify who leaders are in organizations. When lines of authority are clear, organizational communication and coordination are much easier. This also assists with helping leaders predict the outcomes of their work.

Tomorrow’s leadership development coordinators: Breaking the illusion of hierarchical power relationships and demonstrating how people have always had agency to follow their own visions and helping to understand how we can move to more collective forms of leadership by empowering people rather than trying to mandate change is exciting.

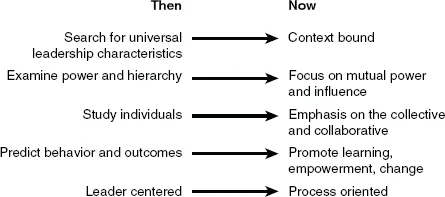

In future years, these may well be the comments of administrators responsible for leadership development on college campuses as leadership development programs move away from traditional scientific management approaches to developing leaders and instead embrace a more revolutionary perspective of academic leadership. As noted in the preface, conceptions of leadership have changed markedly in the last 20 years. Leadership has moved from being leader centered, individualistic, hierarchical, focused on universal characteristics, and emphasizing power over others to a vision in which leadership is process centered, collective, context bound, nonhierarchical, and focused on mutual power and influence processes. These revolutionary assumptions are reflected in the emphasis contemporary leadership scholars place on empowerment, the global dimensions of leadership, cross-cultural understanding, cognitive complexity, and social responsibility for others. These changes are shown in Figure 1.1.

Although leadership development curricular changes are well under way in the business sector, academic leadership programs are just beginning to embrace complexity, globalization, and team-based leadership—three constructs closely associated with revolutionary views of leadership. This book is an attempt to translate and expedite the transfer of revolutionary concepts of leadership into the higher education dialogue and more specifically into the design and implementation of leadership development programs (see Kezar, Carducci, & Contreras-McGavin, 2006, for more details on revolutionary leadership theories and concepts).

In this chapter, we provide an overview of traditional and revolutionary assumptions of leadership and discuss the impact of these assumptions on the format and content of leadership development programs. After synthesizing these two divergent sets of leadership assumptions, we move on to the main focus of the chapter, which is to provide an overview of revolutionary leadership concepts—organizational learning, sensitivity to context and culture, ethics/spirituality, emotions, complexity and chaos, globalization, empowerment and social change, and teams/collaboration. Many of these concepts will be described in greater detail in later chapters. In contrast to the depth provided by these subsequent chapters, our goal is to provide a foundation for understanding and interpreting revolutionary leadership concepts as well as to highlight the characteristics and advantages associated with applying these new perspectives in higher education leadership development programs. The chapters that follow present actual cases of new leadership development programs or hypothesize ways to integrate these new concepts into the curriculum. Another objective of this chapter is to demonstrate the interconnected nature of revolutionary leadership constructs. One of the common dilemmas is that leadership development coordinators become interested in one concept that they add to their program’s curriculum but ignore the many other important innovations that need to be covered in order to create leaders who can be effective in coming years. In this chapter we seek to demonstrate some of the similarities and the synergy that exist between concepts and how they naturally fit together in leadership development curricula.

FIGURE 1.1

The Revolution in Leadership Research

In the end, these revolutionary concepts will require a journey, especially for individuals embedded in traditional scientific management theories. Texts such as Bolman and Deal’s (1995) Leading With Soul and Parker Palmer’s (1990) Leading From Within: Reflections on Spirituality and Leadership underscore how the new assumptions of leadership—social change, empowerment, learning, collective action, mutual power—require leaders to let go of authority, control, power, individualism, and a scientific view of leadership and to embrace what might be a spiritual journey. So to start the journey, readers need to first acknowledge and examine traditional leadership assumptions and how they shape leadership development programs.

Traditional Leadership Development Assumptions and Program Formats

Four main assumptions undergird most contemporary leadership development programs:

1. Leadership is conceptualized as an individual, hierarchical leader.

2. Universal and predictable skills and traits that transcend context best epitomize the work of leaders.

3. Leadership is related to social control, authority, and power.

4. Representations of leadership are value free.

Most leadership development programs tend to focus on individuals who are already (or aspiring to be) in positions of authority. These programs bring in individual leaders rather than teams. Few leadership programs are designed to cultivate all employees as part of the leadership process, a practice at odds with revolutionary leadership principles. Additionally, traditional leadership development programs tend to focus on traits, skills, or behaviors that help an individual in a position of authority to enact leadership. Trait-oriented programs attempt to identify and cultivate specific personal characteristics, such as integrity, commitment, intelligence, and trustworthiness, that contribute to a person’s ability to assume and successfully function in positions of leadership (Bensimon, Neumann, & Birnbaum, 1989). Behavioral models of leadership development call upon participants to examine the roles, categories of behavior, and tasks associated with leadership, such as planning, fund-raising, or negotiation (Bensimon, Neumann, & Birnbaum). Both the trait and behavioral perspectives of leadership rely solely on individual leaders for understanding leadership— context, culture, and other aspects are generally ignored. Program participants are typically asked to reflect on their traits and abilities and to understand their strengths and weaknesses in order to develop a particular character and set of leadership skills. However, leaders are generally not asked to examine these traits in relation to the culture of an organization. For example, they do not consider what honesty might look like or how this trait might be enacted uniquely within their organization or how different individuals within the organization might interpret or understand honesty.

Another underlying assumption of traditional leadership programs is that leaders are responsible for social control and exercising authority. In recent years, as authoritative power structures have been critiqued, leaders have been taught how to ‘‘influence’’ employees so that they do what positional leaders desire, albeit in a more mutual manner, through notions of a shared vision or planning processes where feedback is obtained from stakeholders. What is important to understand is the ability of leaders to use persuasion to achieve desired organizational outcomes. Many leadership development programs focus on ways to influence others and create change, designing learning activities and resources that target the cultivation of abilities associated with persuasion (e.g., effective communication, creating a vision, and allocating rewards and resources). Finally, programs review decision-making processes and focus on principles of efficiency and effectiveness—the hallmarks of scientific management. Authority figures are not asked to focus on ethical or moral consequences and values are de-emphasized within decision making.

Traditional leadership development assumptions have resulted in skill-and trait-based programs aimed at those in authority (or those who aspire to be in authority) that enact universal, context- and value-free strategies. Although we certainly see the value in fostering important traits and skills among positional leaders, we believe leadership development requires a broader emphasis than is currently included in leadership development programs.

Revolutionary Leadership Assumptions

The civil rights and feminist movements of the 1960s and 1970s, coupled with the rapid rise of the global economy, have fundamentally altered contemporary economic, political, social, and cultural interactions and reshaped our understanding of leadership in the process. The social movements resulted in a questioning of traditional authority, examination of abuses of power, recognition and appreciation of differences among people, the power of a collective, and recognition of movements as important social forces for change, willingness to experiment with new ways to approach social processes, and an awareness of ethical aspects of daily decision making. Globalization resulted in multiple, complex forces, such as changing demographics, technology, faster decisions, and greater competition, that require leaders and organizations to abandon outdated scientific management techniques and enact new leadership processes that emphasize interdependence, awareness of cultural and social differences, and adaptability (Lipman-Blumen, 1996, 2000). The revolutionary leadership concepts described throughout this book reflect this changed context of leadership. The leadership revolution explored in this book is guided by five interdependent assumptions:

1. Leadership is a process not the possession of individuals in positions of authority.

2. Culture and context matter; leadership is no longer considered a universal or objective phenomenon that transcends context.

3. Leadership is a collaborative and collective process that involves individuals working together across organizational and national boundaries.

4. Mutual power and influence, not control and coercion, are the focus of revolutionary leadership efforts.

5. The emphasis of revolutionary leadership is learning, empowerment, and change.

The adoption of these revolutionary leadership assumptions has upended traditional notions of leadership as an objective, universal reality characterized by preoccupation with predictable behavior and formal authority. The scientific management views of leadership are slowly giving way to perspectives of leadership that emphasize empowerment, context, reflexivity, cross-cultural understanding, collaboration, complexity, and social responsibility for others (DePree, 1992, 2004; Kezar et al., 2006; Palmer, 1990, 2000). In the following, we elaborate on each of these assumptions and highlight their implications for the design of revolutionary leadership development curricula.

Revolutionary frameworks advance the notion of leadership as a socially constructed phenomenon and thus emphasize the influence of perceptions, interpretations, context, culture, subjective experiences, and the processes of meaning making on leadership practices (Grint, 1997; Kezar, 2002a; Parry, 1998; Rhoads & Tierney, 1992; Tierney, 1988; Weick, 1995). Leadership is no longer understood to be a universal truth or individual possession; instead, it is recognized as a highly complex and ambiguous process shaped by interpersonal interactions and the cultural and social norms of particular contexts. In order to account for and address these complexities, organizations should embrace learning as an essential strategy for adapting and thriving in complex environments and implement leadership development programs that foster in organizational members the skills and values associated with learning (e.g., reflection, environmental scanning, collaboration).

Another revolutionary insight associated with the recognition of leadership as a socially constructed process is the acknowledgment that the perspectives of individuals located throughout the leadership setting, not just those individuals in formal positions of authority, play an important role in shaping leadership contexts and outcomes. Thus, power and influence are understood to be distributed throughout the organization rather than centralized in the hands of a few designated leaders.

The assumption that leadership is a process of shared power and mutual influence is of particular relevance to those revolutionary scholars and practitioners who seek to highlight the historic role of leadership as a tool of social control (Ashcroft, Griffiths, & Tiffin, 1995; Blackmore, 1999; Calas & Smircich, 1992; Chliwniak, 1997; Grint, 1997; Kezar, 2000, 2002a, 2002b; Kezar & Moriarty, 2000; Palestini, 1999; Popper, 2001; Rhode, 2003; Skrla, 2000; Tierney, 1993; Young & Skrla, 2003) and work to disrupt this cycle of oppression by helping organizations establish shared power environments that promote social justice and positive social change (Astin & Leland, 1991; Meyerson, 2003; Meyerson & Scully, 1995). Research has shown that leadership processes capable of empowering historically marginalized individuals and transforming organizations are collaborative in nature and framed by a shared vision for a socially just future (Meyerson; Meyerson & Scully). Thus, individuals committed to enacting revolutionary leadership assumptions seek to cultivate teams, partnerships, and networks with individuals who share their view of leadership as a process of resistance and/or a vehicle for social justice. In addition, social change is not likely to be achieved overnight; revolutionary leadership perspectives emphasize sustained commitment to the leadership enterprise.

Inextricably tied to the revolutionary assumption that leadership is a collaborative process focused on empowerment and social change is the realization that leadership can no longer be framed as a values-neutral phenomenon. Instead, revolutionary scholars emphasize the important role values play in shaping the actions and outcomes of leadership. For example, if the empowerment and social change ambitions of revolutionary leadership are to be realized, individual actions as well as organizational processes must reflect the values of equity, reflexivity, collaboration, empathy, and justice.

The revolutionary assumptions described above hold important implications for the design and implementation of higher education leadership development programs. Rather than continuing to sponsor programs that target positional leaders who operate from a values-neutral, top-down, and context-free leadership paradigm, revolutionary leadership educators should expand their target audience and engage individuals from across the organization as a means of fostering leadership environments that value and enact collaboration, empowerment, learning, and social responsibility. Revolutionary leadership programs should incorporate reflective exercises and collaborative activities that shed light on the context-specific dimensions of leadership, and cultivate among participants the skills and commitment necessary to read and negotiate the ever-changing influences of history, culture, social interactions, and subjective experiences on the leadership process. A more detailed discussion of the development implications embedded within the leadership revolution is presented at the end of this chapter, building upon the distinct, yet interdependent, revolutionary leadership concepts described in the next section.

Revolutionary Leadership Development Concepts

In this section we review the core concepts embedded in the leadership revolution. We introduce and define the concept, explain how it relates to the new leadership assumptions, and introduce some main thinkers and resources. We also review a few ways leadership training might be altered to embrace the concept. For more detail on some of these concepts, see Kezar et al. (2006).

Promoting Individual and Organizational Learning

When leadership is assumed to be a mutual power and influence process and involves a collective of individuals who are working to create change, organizational learning becomes critical to fulfilling this new mandate for leadership. It is no longer sufficient for a set of leaders with positions...