![]()

SECTION 1

Introducing the Struggle and the Authors

–Arnold Townsend, San Francisco pastor and member of the San Francisco State Black Student Union Presidium (Townsend, 2019)

Part 1: Introducing the Struggle

THE SAN FRANCISCO STATE strike of 1968 was one of the most successful campus movements in U.S. history. It guaranteed a place for Black students and Black scholarship in higher education within the United States and abroad. This remarkable feat was accomplished by young Black working-class men and women and their allies, all of whom lacked money or traditional political influence.

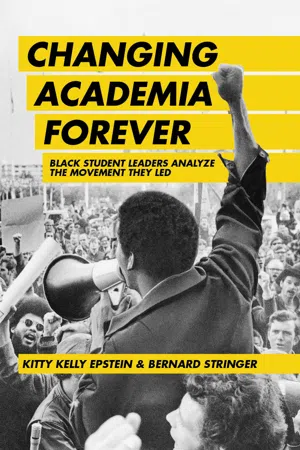

For a long time, the strike was largely ignored by academics and harshly criticized by governmental bodies. The only academic book, written a year after the strike, was authored by Robert Smith, the college’s president, who was forced out of office by the strike and was, unsurprisingly, somewhat dismissive of its results (Smith, 1970). But decades of hindsight can provide perspective, and by 2010 the San Francisco Chronicle was calling the strike at San Francisco State the event that “changed academia forever” (Van Niekerken, 2018).

This book takes a deep look at how the strike’s success was made possible and what it means for modern-day activism. Several recent scholars have included a chapter on the strike (Biondi, 2012; Rojas, 2010). A dissertation discusses the relationship of the strike to the communities of San Francisco (Ferreira, 2003), and another makes the case that the movements at the City University of New York and San Francisco State were the most successful of their kind (Ryan, 2010). The present volume is the first full-length study devoted to the strike and the first to focus on the leadership of the Black Student Union.

The significance of San Francisco State can be measured both by its support and its impact. Thousands of students stayed away from classes, picketed daily, and rallied regularly. The campus was essentially shut down for four and a half months. A one-day survey taken by the college in January 1969 found that only 37% of scheduled classes were meeting, and all of those had less than 50% attendance. There were 800 arrests. Although only 4% of the students were Black, a mostly white campus followed their leadership. The faculty members’ chapter of the American Federation of Teachers went on strike in solidarity in January 1969.

And the strike was victorious. Most of the strikers’ fifteen demands were met. The first Black Student Union in the country was formed. The first College of Ethnic Studies in the country was created. Black, Latino, Asian, and indigenous faculty were hired. The Black Studies Department opened immediately, and its first graduate had his degree by 1970. Finally, the state’s master plan for tracking higher education was challenged.

This book interweaves events and analyses with the life histories of its fascinating participants. It uncovers facets of this particular student movement that have thus far remained unexplored.

For example, the socioeconomic status of the strike leaders was quite different from the leaders on other, more affluent campuses. Many of them were first-generation migrants leaving the terrors of the Jim Crow South. All of them were working-class people who had to struggle for food and rent money while carrying on the strike, and they had a vision for Black Studies that was different from the more academic interpretation. They had intense relationships with the Black community. As a child, Danny Glover watched the San Francisco movement grow, because his parents were local union leaders. Bernard Stringer got many of his meals from the parents of children he worked with in the Western Addition neighborhood. These two men were not self-consciously “creating allies” or “looking for support”; instead, they were relying on their own deep relationships with friends and neighbors for survival and political insight.

One reason why the voices of the San Francisco State leaders have not been heard amid the growing interest in student movements of the 1960s is their relative modesty and collaborative leadership model. Together they created a politics and strategy through hours of discussion and, for the most part, did not try to compete with each other for acknowledgment of such. Although people lost jobs and money and sometimes spent many months in jail, one hears few complaints about who got the credit. These leaders intended for the emerging Ethnic Studies departments to have the same relationships and the same approach to knowledge that their community relationships afforded them. They honored the idea of “theory into practice,” with the intention that Black Studies would operate in direct service to the Black community.

This movement was not spontaneous (Thompson, 2004). Of course, as we will see, particular events took on a life of their own, but there was an overall strategic plan for organizing all the Black students on the campus and changing Black America.

Another insight, one that remains critical to modern-day activists, is the essence of their political outlook. “Integration” was being replaced by “self-determination” as a goal. Did that mean they wanted nothing to do with whites? Clearly not, since often a majority of the picketers were white. In fact, Bernard Stringer asserts that the strike could not have been won without the “white mother-country radicals.” So what did revolutionary nationalism and self-determination mean?

It is hard to place oneself in the context of the 1960s, because so much of what we take for granted did not exist at that time. Before 1967, Black students were called Negroes. There were no Black Studies programs, and there were very, very few Black faculty or students on college campuses in the North. Student governments and student newspapers were all white. And much of what Americans learned in public school was a rehash of Confederate mythology. Little children read about “Black Sambo,” and older children were taught that Blacks and white Northerners had messed up the South in the period after the Civil War when they won the vote (Zimmerman, 2004).

College students did not learn much about Black people at all, except for a few pages in a general history or political science text. But the San Francisco State strikers themselves were hungry for knowledge about Black people, hungry enough to make great sacrifices to attend the few classes on the subject that existed prior to the strike (Stewart, 2019).

The strikers had goals far more wide-reaching than rectifying some racist textbooks. The emergent Black Student Union wanted to change the entire paradigm of American higher education by creating and naming an institutional space for Black scholars who would work at solving the problems of the Black community, asserting self-determination over that space, and welcoming Black students into the institutions that their parents’ taxes had long been paying for.

The strike ultimately resulted in universities meeting most of the demands made by the Black Student Union, first at San Francisco State and then across the country. A College of Ethnic Studies was created, and 150 Black Studies departments were born. Other successes followed: hundreds of African-Americans became faculty at these institutions; the body of knowledge about Black history and economics expanded; an international movement was born; a national Black Studies organization was created; and thousands of Black students were admitted to four-year institutions. Movements calling for multicultural education blossomed, movements that have recently resulted in ethnic studies requirements in many U.S. high schools. Federal financial aid was modified, and programs for educational opportunity were embedded in most institutions. In addition, beyond the immediate demands, the strategic political approach of revolutionary nationalism was developed, which, we will argue, has had a long-term international impact on the culture and politics of Black people in particular, and U.S. thinking in general.

Of what use is such a study of the Black Student Union and the San Francisco State strike? This movement was uniquely effective. Why? What was it about the leadership practices, the leaders, the organizing, the demands, the politics, or the coalition that made it work, or was it all of those things? Might this movement suggest something about what mass movements will look like, if a movement large enough to fundamentally change the society is to occur?

The sources for the book are many. One author, Bernard Stringer, was a member of the Central Committee of the BSU. He also conducted extensive interviews with other strike leaders in preparation for writing the book. Additional conversations with some of the strike leaders were carried out by Kitty Kelly Epstein during the writing of the book, as well as some personal communications with non-leaders whose lives were altered by the events. Archival material was collected by Bernard between 1968 and 2019. The authors also made use of materials available in the archives of the San Francisco State College Library.

In this section we explain the organization of the book and introduce the authors. In Section 2 we discuss the reasons why and how this most significant strike occurred on what had previously been a little-known California college campus. We include the stories of two early leaders, Dr. Jimmy Garrett and now-attorney Jerry Varnado, and we illuminate the emerging politics of the Black Student Union. In Section 3 the campus struggles that came before the strike are detailed, along with the stories of additional strike leaders. In Section 4 we discuss their demands, the beginning of the strike, and the story of Terry Collins. Section 5 treats the allies of the BSU, which included the Third World Liberation Front, the local chapter of the American Federation of Teachers, the white student organizations and individuals, and the Black and Latino communities of San Francisco, and it includes an interview with film actor and producer Danny Glover, who was a leader of the 1968 movement. Section 6 examines the implementation of Black Studies and other demands and the national impact thereof, providing more stories that illuminate the points with personal details. Section 7 provides life stories of two BSU activists who attempted to carry out the BSU philosophy of serving the community after the strike ended. Section 8 analyzes the political implications and the causes for the strike’s success.

The book neither attempts to provide a chronology of every event before, during, and after the strike nor seeks to include every political or academic leader who played a role in the strike. Such chronologies already exist, particularly in the San Francisco State College Library archives.

Because the purpose of the book is not to provide yet another chronology, each section is organized in a way that integrates an understanding of strike leaders and participants with the events and politics of that period in the San Francisco State struggle. Each section contains one or two life stories, a discussion of a particular period in the SF State struggle, and an analysis of some aspect of the politics or strategy. Thus, for example, Section 2 begins with the life stories of two of the early organizers, Varnado and Garrett, proceeds to a discussion of some of the early organizing, and concludes with an elaboration on the politics of the emerging BSU.

We begin with the life stories of the authors.

Part 2: Introducing the Authors

Introducing Bernard

“I am the first person to ever earn a degree in Black Studies. San Francisco State had the first department, and I was its first graduate.

“All the people I have ever met who were involved in the San Francisco State Strike have told me that it changed their lives. We are beginning this book with a bit of my own story, so that readers can understand who we were and the amazing changes in education and in ourselves that we helped to birth.

“I was raised in Bogalusa, Louisiana, by my elderly aunt Mary and her blind boarder, James May. Aunt Mary suffered a paralyzing stroke when I was six years old, after which I became the accountable person for two disabled elderly adults. Life was very basic. We had electricity but no inside bathroom or refrigerator. We cooked on a wood stove, and I did the errands and the bill payments at six years of age. There was a Black school and a white school in Bogalusa. The Black school used all the hand-me-downs from the white school, and we had all Black teachers who were very caring. Bogalusa was a lawless sawmill town where 15 Black people were killed by whites at Live Oak Church. No white man was ever convicted of killing a Black man in Bogalusa in the twentieth century.

“My aunt Mary passed on to her homecoming when I was 9 years old. My cousin and my sister came to Aunt Mary’s funeral and took me back to Oakland, California, by train. I got to play with my sister for the first time. When we arrived in Oakland, I could have all the food I wanted, and I could sit anywhere I wanted in the movie theater.

“After 2 weeks in Oakland, my grandfather, Roosevelt Stringer, arrived to take me home with him to Fresno. He was 6 feet, 6 inches tall, weighed 250 pounds, and worked 361 days a year. The other 4 days he took off to see the Giants or the Dodgers play baseball. He and my neighbor, Jack Gaines, were my mentors. Jack Gaines was the first person to tell me I was a slave. What did he mean? A slave to what?

“During the summer between my sophomore and junior years, I was practicing for football season at Edison High. Coach Masini, the varsity football coach, told me I would not be able to play for him. That hurt and insulted me and led me to think about how to get away from him. Because of Brown v. Board of Education, we were able to choose a different high school, and I went to Fresno High. Academics took hold, and the school had better equipment. This was the beginning of a whole different world for me, but I could never leave my culture behind.

“At Fresno High I was the first-line defensive tackle. I was not only on the team, but I made first string. How you like me now, Coach Masini?

“My grandfather had a third-grade education, and he told me that education was the one thing that could not be taken away from Black people. I went to Reedley Community College in Reedley, California, after high school, and one of the speakers at my Reedley orientation told me that ‘only four in ten of you will finish college with a 4-year degree.’ I made up my mind that I was absolutely going to be one of those four.

“I visited different areas of California as part of the Reedley football team. I fell in love with San Francisco and applied to San Francisco State. The SF State team was white and Black and Mexican, and we all got along well. I remember one incident in Chico, California, when the State team played there. The hotel deskman asked my roommate if he wanted to be paired with a Black man, and my teammate had some very bad words for him.

“Our football team was successful, but I had to turn down going to a bowl game because I didn’t have any money, and I had to find steady work. I had only a noontime monitoring job watching the children at John Muir Elementary; we got lunch for 25 cents before the children came down to the cafeteria. And the parents at John Muir Elementary were saviors in terms of home-cooked meals. I found the Black community willing to help Black college students in any way they could, with plenty of love.

“The summer of 1967 changed my life. By then I had a job with more hours, and I had enough money to rent a flat in the Western Addition with three other brothers. We were sitting on our front steps drinking tequila one day when my homeboy from Fresno, Marvin X, who was ...