1 The standard text

1.1 Economics is the science of choice

It seems obvious that economics is about the economy; so a common sense definition of economics might be that it concerns itself with money, markets, business and how people make a living. But this definition is too narrow. Economics is not just the study of money and markets. It studies families, criminal behaviour and governments’ policy choices. It includes the study of population growth, standards of living and voting patterns. It can also have a shot at explaining human behaviours in relation to dating and marriage.

The fact that economics can examine subjects traditionally studied by other social sciences suggests that content does not define the discipline. As long as a topic has a social dimension, we can look at it from the perspective of any social science.

Most textbooks define economics as the science of choice. It’s about how individuals and society make choices, and how those choices are affected by incentives. This definition includes all aspects of life: a couple’s choice to have a child, or a political party’s choice of its platform. Its drawback is that it doesn’t help to differentiate economics from the other social sciences, since they too look at how we make choices.

What distinguishes economics from other social sciences is its commitment to rational choice theory. This assumes that individuals are rational, self-interested, have stable and consistent preferences, and wish to maximize their own happiness (or ‘utility’), given their constraints – such as the amount of time or money that they have. Social situations and collective behaviours are analysed as resulting from freely chosen individual actions. Just as science attempts to understand the properties of metals by understanding the atoms that comprise them, so economics attempts to understand society by analysing the behaviour of the individuals who comprise it.

1.2 Scarcity

Why is choice necessary? Economics assumes that people have unlimited wants. Therefore, no matter how abundant resources may be, they will always be scarce in the face of these unlimited wants.

A fundamental question in economics has always been how do we maximize happiness? Economists maintain that while we must allow people to decide for themselves what makes them happy, we know that people always want more. Therefore, society needs to use its resources as efficiently as possible to produce as much as possible; and society needs to expand what it can produce as quickly as possible. This explains why economists emphasize the goals of efficiency and growth.

But does the concept of unlimited wants mean that someone will want an unlimited number of new coats, or an unlimited number of pairs of shoes? No, it doesn’t. Along with unlimited wants, economists normally assume that the more you have of something, the less you value one more unit of it. So, unlimited wants does not mean we want an unlimited amount of a specific thing. Rather, it means that there will always be something that we will desire. There will always be new desires. Our desires and wants are fundamentally unlimited.

1.3 Opportunity cost

Since resources are scarce, if we choose to use them in one way, we can’t use them in another. Choosing more of one thing implies less of another thing. In other words, everything has a cost, and the real cost of something is what must be given up to get it. This is its opportunity cost – the value of the next best alternative forgone.

It’s a cliché that there’s no such thing as a free lunch – there is always an opportunity cost. Even if someone else buys you lunch, there is still a cost. There is a cost to society for all the resources used to grow the food, ship it to the restaurant and have it prepared. Your free lunch even costs you something: it uses up some of your scarce time that you could have used to do something else.

1.4 Marginal thinking: costs and benefits

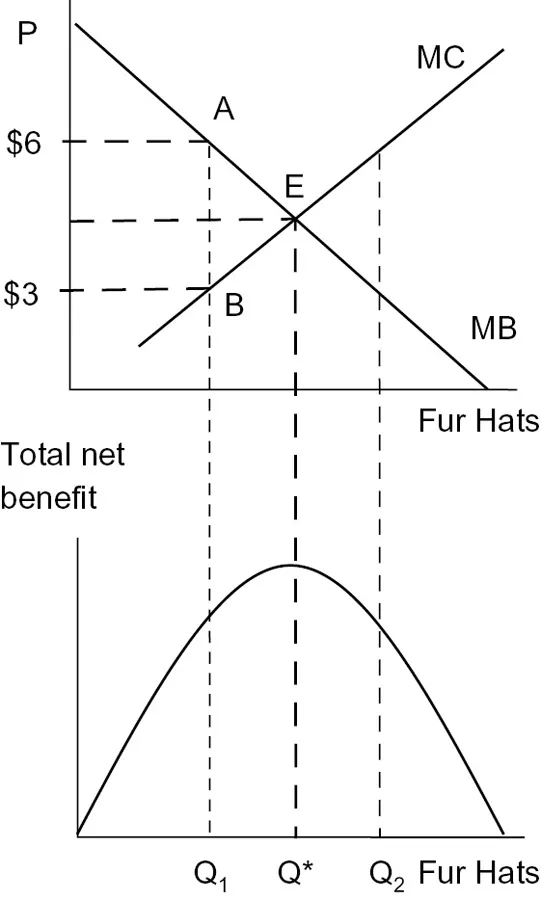

You are familiar with the margin on a page – it lies at the edge. And when someone describes a soccer player as being marginal they mean he is a fringe player, on the edge of inclusion. Economists use the word marginal in a similar way. Marginal cost is the cost at the margin – or to be more precise, the cost of an additional unit of output or consumption. Thus, the marginal cost of wheat is the additional cost of producing one more unit of wheat. Similarly, marginal benefit is just the benefit someone gets from having one more unit of something. We might measure benefit in hypothetical utils of satisfaction; or in dollar terms – the maximum willingness to pay for one more unit. As the science of choice, the core economic framework is remarkably simple: all activities are undertaken to the point where marginal cost equals marginal benefit. Why? Because at this point total net benefit is maximized. An example will help.

Imagine we are old-style Soviet planners, trying to determine the quantity of Russian-style fur hats to produce. Let’s assume that the marginal cost of producing a fur hat increases the more we produce – so we draw it as the upward-sloping line in the upper diagram of Figure 1.1. Further assume that the more hats are produced, the less one more hat is valued – so the marginal benefit line slopes down. How many hats should we produce? If we produce only Q1 units, the marginal benefit of one more hat is $6, but the marginal cost is only $3. This means that the extra benefit of one more unit is greater than the extra cost of producing it. Therefore, we can improve society’s well-being by producing one more. This remains true as we increase production to Q*. But we should not produce more than Q*. Beyond that point marginal cost exceeds marginal benefit, reducing total net benefit from hat production. Total net benefit is shown in the lower diagram of Figure 1.1. Clearly, this is maximized at an output of Q*.

This marginal-cost/marginal-benefit framework can be applied to everything we do, buy, hire or produce. If I want to maximize my satisfaction from studying economics, I should study until the marginal cost of one more hour of study just equals the marginal benefit. If I want to maximize my satisfaction from buying oranges, I equate marginal cost to the marginal benefit of one more orange.

When textbooks claim ‘rational people think at the margin’ it is this framework they have in mind. But are people rational?

1.5 Rational and self-interested individuals

Critics claim the foundations of economics are shaky – people are not rational, they say, nor solely self-interested. But rationality in economics means something quite different from its colloquial meaning. All it means in an economic context is that individuals are goal oriented and have consistent preferences (or tastes). So if John prefers apples to oranges, and oranges to grapefruit, he must prefer apples to grapefruit.

Economists assume everyone has the same fundamental goal: to be as happy as possible, or (to use economic jargon) to maximize their utility (or satisfaction). But different things bring happiness to different people. One person prefers to give their money to charity and live a simple ascetic life. Another prefers to spend their money on the fast life – the American comedian W. C. Fields famously quipped, ‘I spent half my money on gambling, alcohol, and wild women. The other half I wasted.’ Economists do not judge the things that bring utility to people. To be ‘rational’ in economics simply means that given your preferences, you choose to allocate your time and money to maximize your utility.

Further, individuals are not assumed to think only of themselves. Someone’s utility may depend on the well-being of others. The altruist is viewed as no better or worse than the miser, since they are both trying to be as happy as possible. Selfish and selfless, virtue and vice, have no meaning in economics – they’re just different preferences.

If individuals are rational, they respond to incentives in predictable ways. Thus, if we wish to encourage people to give blood we could pay them for their time. Or, if we wish to encourage people to recycle bottles, we could make them pay a bottle deposit that is refunded upon return.

1.6 Markets are usually a good way to organize economic activity

We don’t need economic planners; as long as we have competitive markets they organize the economy in a way that maximizes the value of total production and thus the incomes that are earned by producing it. This is better than the perfect planner for two reasons: first, it doesn’t require an expensive planning bureaucracy; second, it doesn’t require that anyone be altruistically motivated.

We will develop the argument over several chapters, but let’s have a quick synopsis right now. Here it is in three sentences:

In competitive markets, prices and quantities are determined by demand and supply. But demand is just marginal benefit, and supply turns out to be just marginal cost. So, competitive markets guarantee that the right quantities are produced and society’s net benefit is maximized.

This is the technical argument for laissez-faire, the view that governments should leave the economy alone. Let's consider the argument developed by Adam Smith in The Wealth of Nations, published in 1776. In an analogy that has become iconic, Smith compares competitive market forces to an invisible hand that guides self-interest into socially useful activities. He wrote: ‘It is not through the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer or the baker, that we expect our dinner, but from their regard to their own interest.’ In a later passage he added: ‘Every individual… by directing that industry in such a manner as its produce may be of the greatest value, he intends only his own gain, and he is in this, as in many other cases, led by an invisible hand to promote an end [the public interest] which was no part of his intention.’2 The novel twist in Smith’s argument is that he turns selfishness into a virtue. Government intervention is not needed because a competitive market system naturally leads to a harmony of interests. In Smith’s example, it leads to the optimal quantities and lowest possible prices for meat, beer and bread. In other words, it leads to an efficient outcome.

1.7 Governments can sometimes improve market outcomes

The central message is this: if all markets were competitive and there were markets for everything, laissez-faire would produce an efficient outcome in three key aspects: it would produce the optimal quantity of each good; it would produce these quantities at the lowest possible cost; and it would distribute the output to those who ‘value’ it most. This situation is called Pareto optimal, and it has the property that it is not possible to make anyone better off without making at least one person worse off – in other words, there would be no waste anywhere in the economy.

The condition that all markets must be competitive can be violated in two ways, however. First, some markets may be non-competitive, as in the case of monopoly (a single seller). Second, some markets may not exist, such as the market for unpolluted air. Both cases lead to ‘market failure’. In such situations, government intervention can (in theory) improve upon the inefficiency produced under laissez-faire. Thus, the role of the government is critically dependent on two factors: first, how competitive existing markets are; and second, upon how many markets don’t exist.

1.8 Another government role: providing equity

In the special situation of complete and competitive markets, laissez-faire leads to a Pareto-optimal situation – an ideal situation in an efficiency sense. But that doesn’t mean that the outcome would be fair or humane. It might be a situation where widows and orphans are starving while everyone else has three homes and a luxury yacht. So the government has an...