eBook - ePub

Gender, Criminalization, Imprisonment and Human Rights in Southeast Asia

This is a test

- 272 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Gender, Criminalization, Imprisonment and Human Rights in Southeast Asia

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This volume contains two Open Access Chapters.

Gender, Criminalization, Imprisonment and Human Rights in Southeast Asia features contributions from activist scholars grappling to understand and alleviate the compound sufferings of women and LGBTIQA+ persons as they encounter Southeast Asian criminal justice systems. The collection demonstrates that it is critical that the drivers of gendered harms and the way gendered needs intersect with other inequalities are better understood and adequately reflected in law, policy and practice.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Gender, Criminalization, Imprisonment and Human Rights in Southeast Asia by Andrew M. Jefferson,Samantha Jeffries in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Criminology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Introduction to Gender, Criminalization, Imprisonment and Human Rights in Southeast Asia

Abstract

In this introductory chapter, we discuss the impetus for this edited book. We introduce activist, critical and feminist criminological theorizing and research on gender, intersectionality, criminalization, and carceral experiences. The scene is set for the chapters to follow by providing a general overview of gender, criminalization, imprisonment, and human rights in Southeast Asia with particular attention being paid to Indonesia, Malaysia, Cambodia, Thailand, Myanmar, and the Philippines. We consider trends and drivers of women’s imprisonment in the region, against the backdrop of the United Nations Rules for the Treatment of Women Prisoners and Non-Custodial Measures for Women Offenders, also known as the Bangkok Rules, which were adopted by the United Nations General Assembly just over a decade ago. We reflect on the dominance of western centric feminist (and malestream) criminological works on gender, criminalization and imprisonment, the positioning of Southeast Asian knowledge on the peripheries of Asian criminology and the importance of bringing to light, as this book does, gendered activist scholarship in this region of the world.

Keywords: Gender; criminalization; imprisonment; human rights; Southeast Asia; feminism; activism; critical criminology

Setting the Scene

Throughout history, women in conflict with the law and those behind prison walls, have been afterthoughts, often ignored because of their small numbers, making them a relatively invisible or forgotten population (Chesney-Lind, 1998; Jeffries, 2014; Owen, Wells, & Pollock, 2017). As a result, criminal law, justice systems, and prisons across the world have shown little evidence of gender sensitivity in policy or practice, leading to discrimination, social exclusion, and violations of human rights. The absence of gender-sensitive perspectives results in systems that are structurally blind to gender-specific challenges and harms within the field of criminal justice in general, and particularly in prisons. It is critical that gendered needs, including how these intersect with other forms of inequality, are paid more attention, better understood, and adequately reflected in law, policy and practice.

Over the last several decades, the number of detained women worldwide has surged (Walmsley, 2017). Women are no longer as invisible as they once were and concurrently, there has been increasing recognition of their human rights when they come into conflict with the law, and especially behind prison walls (Penal Reform International & Thailand Institute of Justice, 2021; United Nations General Assembly, 2010). Just over a decade ago, the United Nations Rules for the Treatment of Women Prisoners and Non-Custodial Measures for Women Offenders, also known as the Bangkok Rules, were adopted by the 193 countries at the United Nations General Assembly (2010).

The adoption of the Bangkok Rules has not interrupted increases in women’s imprisonment, even though the Rules contain important commitments concerning non-custodial alternatives that should have reduced population numbers (Fernandéz & Nougier, 2021, p. 4). In Southeast Asia, as is the case globally, there have been substantial upward trends in women’s detention (Jeffries, 2014; Jeffries & Chuenurah, 2016; Walmsley, 2017; World Prison Brief, 2021). This expansion in the region is being driven by heightened punitiveness, including government “crackdowns” on the illicit drug trade, human trafficking, and immigration (Jeffries, 2014).

Most notably, the war on drugs (global and local) has resulted in large numbers of women being imprisoned throughout Southeast Asia (Chuenurah & Sornprohm, 2020; Fernandéz & Nougier, 2021; Jeffries, 2014; Jeffries & Chuenurah, 2016). Sentences for drug offending are harsh, incorporating long-term incarceration, mandatory life, and the death penalty in all but two Southeast Asian countries (Cambodia and the Philippines). Furthermore, the number of people being incarcerated pre-trial, and thus presumed innocent, is skyrocketing. In the Philippines, for example, drug laws establish mandatory pre-trial detention (Chuenurah & Sornprohm, 2020, p. 132; Fernandéz & Nougier, 2021, p. 7; Penal Reform International & Thailand Institute of Justice, 2021). While figures by gender are not publicly accessible, data provided by the World Prison Brief (2021) show that in some Southeast Asian countries, around 7 out of 10 people in prison are pre-trial detainees. The overall result is prison overpopulation. Aside from Singapore, all prisons in the region are at over 100% capacity, with some sitting above 400% (Table 1). Custodial overcrowding and concomitant under-resourcing pose obstacles to protecting the human rights of those deprived of liberty, including with regard to healthcare, education, and humane treatment (Chuenurah & Sornprohm, 2020, p. 132; Fernandéz & Nougier, 2021, p. 19; Penal Reform International & Thailand Institute of Justice, 2021). It is important to stress, that representing overcrowding in numerical terms fails to do justice to the experience of living under these conditions. As argued by Schmidt and Jefferson (2021, p. 82),

overcrowding, we believe, cannot be understood only as a quantitative category. It is not about percentages or about exceeding capacity but bodies in close proximity, living, breathing, infectious, aching, sick, damaged, and sensorially extreme.

Table 1. Pre-Trial Detention and Prison Overcrowding in Southeast Asia.

Source: World Prison Brief (2021).

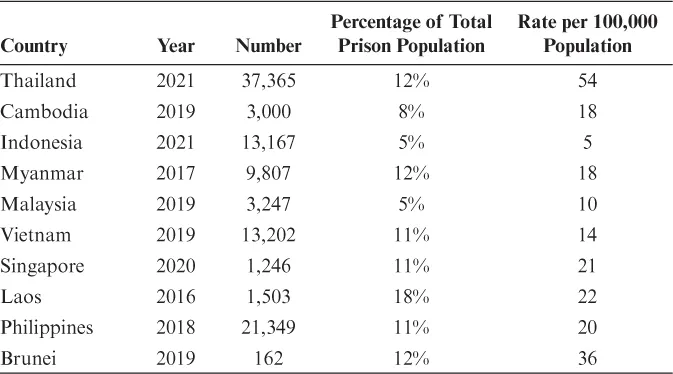

In 2017, the World Prison Brief listed the top 10 countries with the highest female prisoner numbers, in which 5 were in Southeast Asia: Thailand, the Philippines, Indonesia, Vietnam, and Myanmar (Walmsley, 2017). On average, globally, women constitute around 7% of the total global prison population, and are incarcerated at a rate of 9.9 per 100,000. As demonstrated in Table 2, both figures are higher in nearly every Southeast Asian country. The overuse of imprisonment for women in Thailand is particularly stark, with more women in prison here than elsewhere in the region. Furthermore, after the United States, Thailand has the second highest rate of female incarceration in the world (Chuenurah & Sornprohm, 2020, p. 135; Walmsley, 2017; World Prison Brief, 2021).

Table 2. Females Imprisoned in Southeast Asia.

Source: World Prison Brief (2021).

The Impetus for this Book

In proposing this book on Gender, Criminalization, Imprisonment and Human Rights in Southeast Asia in the Emerald Activist Criminology series, our objective was to capture and collate the emerging work of activist scholars and grass-roots advocates grappling to understand the lived experiences of cisgender women, transgender persons, other gender, and sexual minorities, as they encounter criminal justice systems in Southeast Asia. Exploring the complex interplay between conditions, needs, experiences, identities, and trajectories, our goal in the text that follows is to add significantly to our knowledge of the practices of gendered violation, victimization, and vulnerability facing people in conflict with the law and behind prison walls. Covering a range of country contexts – Indonesia, Malaysia, Cambodia, Thailand, Myanmar, the Philippines – and attentive to the variegated gendered experiences of different people on their way into, through, and/or beyond prison, this book contributes toward the development of theoretical and policy-oriented perspectives that are empirically grounded, rather than based on a presumed uniformity of experience.

For the most part, criminological scholarship undertaken within Asian societal contexts has been dominated by academics researching in a limited number of countries, employing masculinist theoretical paradigms (Lee & Laidler, 2013; Moosavi, 2019a). While we have witnessed advancement in criminological knowledge production from East Asia, including Japan, Hong Kong, China, South Korea, and Taiwan, some countries remain on the periphery within the Asian ambit (Lee & Laidler, 2013, p. 144). These tangential sites comprise Southeast Asian countries such as Malaysia, Cambodia, Thailand, Indonesia, Myanmar, and the Philippines (Belknap, 2016, p. 253; Lee & Laidler, 2013, p. 144). Furthermore, even among the relatively active centers of criminological knowledge production in East Asia, most work focuses on testing and reproducing western criminological scholarship, frameworks, and knowledges (Belknap, 2016, p. 256; Lee & Laidler, 2013, p. 150). This work generally coalesces within the domain of new right realist criminology, being “administrative, positivist, quantitative and geared toward reducing crime from a state perspective” (Moosavi, 2019, p. 266). Issues of power, including gender, class, race/ethnicity, and sexuality have not been central to the research agendas of criminologists researching in East Asian countries (Belknap, 2016; Moosavi, 2019, p. 266).

Yet, for the editors of this book, what has become increasingly obvious after years of undertaking collaborative research in Southeast Asia, is the emergence of a burgeoning collection of critical criminological scholarship in the region, including gendered activist work. These endeavors are not limited to academe; they include collaborations with those working at the “frontline” in human rights organizations, NGOs, and government, all of whom seek to effectuate positive change in criminal justice policy, practice, and more broadly. The primary aim of this book is to make this more critical body of work visible.

In contrast to administrative or right realist criminology that has dominated criminological work undertaken in Asia to date, critical criminology is concerned with issues of social structural power. Those working within this activist framework make evident the injustice of criminal justice, and unpack how systems of power mark experiences of criminalization and imprisonment. Ultimately, the aim is the creation of a more socially just society across numerous domains, including, and especially within (and sometimes also against) the criminal justice system (Arrigo, 2016; Belknap, 2016; DeKeseredy & Dragiewicz, 2018; White, Haines, & Asquith, 2017, pp. 209–230).

Feminist Criminology, Human Rights and the Chapters that Follow

Feminist criminology sits within the critical criminological paradigm. The collective goal is to speak truth to patriarchal power by centering and valuing the voices of criminalized women and raising awareness of gender oppression (Barberet, 2014, p. 16; Belknap, 2016, p. 14). Ultimately, feminist criminologists have tasked themselves with calling out gendered injustice and advocating for change in the conditions of criminal justice and society more broadly, that is harmful or oppressive to women in conflict with the law (Barberet, 2014, p. 16; Belknap, 2001; Britton, 2000; 2004; Carlen, 1985; Chesney-Lind, 1997; Daly & Chesney-Lind, 1988; Miller & Mullins, 2008; Renzetti, 2018, p. 75). Explicitly or implicitly, feminist activism presents as the prevailing theme throughout this book. More specifically, the authors of the chapters that follow build on two bodies of feminist criminological work that has, until recently, been dominated by western scholarship – pathways and feminist explorations of women’s imprisonment.

Beginning with Daly’s (1994) seminal work in the United States, feminist pathways researchers have mapped the life experiences leading women into the criminal justice system, exploring how gender shapes criminalization. These studies revealed a particular and shared gendered backstory in the lives of women who come into conflict with the law, which is qualitatively different from that of men (Evans, 2018, pp. 41–43; Miller & Mullins, 2008, pp. 229–232; Wattanaporn & Holtfreter, 2014). Women’s pathways are generally characterized by histories of gender-based violence (e.g., sexual and domestic abuse), associated trauma, substance abuse, economic marginalization, caregiving, problematic familial relationships, and intimate entanglements with men (see Daly, 1994; Owen et al., 2017; Wattanaporn & Holtfreter, 2014 and for studies in Asia, see Cherukuri, Britton, & Subramaniam, 2009; Khalid & Khan, 2013; Kim, Gerber, & Kim, 2007; Jeffries & Chuenurah, 2018; Jeffries & Chuenurah, 2019; Jeffries, Chuenurah, Rao, & Park, 2019; Jeffries, Chuenurah, & Russell, 2020; Jeffries, Rao, Chuenurah, & Fitz-Gerald, 2021; Russell, Jeffries, Hayes, Thipphayamongkoludom, & Chuenurah, 2020; Shen, 2015; Veloso, 2016).

At its core, feminist pathways scholarship highlights how patriarchal social structures play out in the lives of criminalized women, oppressing them through interpersonal, family, and state-sanctioned abuses (e.g., political and economic marginalization). Rather than pathologizing women and seeing their offending as something inherent at the level of the individual, feminist pathways scholars have sought to locate women’s criminalization within social structural forces intimately related to gendered power relationships and associated access to resources. Women, it is argued, are frequently criminalized for exacting behaviors of survival within contexts of patriarchal subjugation (Willison & O’Brien, 2017).

In this book, Veloso (Chapter 9), and Russell and co-authors (Chapter 7) have specifically applied a feminist pathways approach to explore the imprisonment trajectories of women formerly on death row in the Philippines, and older women incarcerated in Thailand. The research findings presented in both chapters mirror the themes of previous feminist pathways studies. For the women in Veloso’s (Chapter 9) study, economic precarity, victimization, and addiction were dominant themes in their lives, alongside deception, betrayal, and corrupted patriarchal systems of justice. Russell, Jeffries, and Chuenurah (Chapter 7) conclude that the older women in their research had either come into conflict with the law because they were providing for their families against the backdrop of poverty, took “the fall” for loved ones, or had self-medicated with illicit drugs in response to adversity and victimization.

The centrality of pre-existing conditions of gendered social structural vulnerability, putting women at risk of criminal justice system involvement, is highlighted in other chapters. Jefferson and co-authors (Chapter 2) discuss how the criminalization of certain behaviors, normative expectations of womanhood, poverty, relationships, gender discrimination in law, access to justice, and treatment in the criminal justice system, alongside the patriarchy of the Tatmadaw (armed forces), especially in the aftermath of the 2021 military coup, underpin women’s imprisonment in Myanmar. Harry (Chapter 3) highlights the gendered vulnerabilities of women sentenced to death in Indonesia and Malaysia. Gorter and Gover (Chapter 4) note that women behind prison walls in Cambodia often come from poor, disadvantaged backgrounds, and lack legal literacy. Rao and co-authors (Chapter 6) highlight similar themes in the life histories of ethnic minority women imprisoned in Thailand.

Around the same time that Daly (1994) was writing, other scholars were attempting to understand the backgrounds and experiences of incarcerated women, alongside the collateral damages of carcerality through a feminist lens (e.g., Bosworth & Carrabine, 2001; Carlen, 1985; 1998; Chesney-Lind, 1991; Owen, 1998; Pollock-Byrne, 1990). In terms of the former, findings align with feminist pathways scholarship. Regarding the latter, women’s time in prison was characterized by multiple interlocking gendered harms ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Tables

- About the Contributors

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1. Introduction to Gender, Criminalization, Imprisonment and Human Rights in Southeast Asia

- Chapter 2. Gender and Imprisonment in Contemporary Myanmar

- Chapter 3. Perpetrators and/or Victims? The Case of Women Facing the Death Penalty in Malaysia

- Chapter 4. Supporting Female Prisoners and Their Families: The Case of Cambodia

- Chapter 5. Catching Flies: How Women are Exploited Through Prison Work in Myanmar

- Chapter 6. Experiences of Ethnic Minority Women Imprisoned in Thailand

- Chapter 7. Older Women’s Pathways to Prison in Thailand: Economic Precarity, Caregiving, and Adversity

- Chapter 8. Transgender Prisoners in Thailand: Gender Identity, Vulnerabilities, Lives Behind Bars, and Prison Policies

- Chapter 9. Gendered Pathways to Prison: Women’s Routes to Death Row in the Philippines

- Chapter 10. Expanding the Promise of the Bangkok Rules in Southeast Asia and Beyond

- Chapter 11. Conclusion: Decentering Research and Practice Through Mutual Participation

- References

- Index