![]()

1

Navigating Topics and Creating Research Questions in Linguistic Anthropology

Farzad Karimzad and Lydia Catedral

1.1 Introduction

Research in linguistic anthropology—like research in any field—is not so much defined by particular questions, but rather by a specific way of approaching, addressing, and organizing these questions. At any given time, the same phenomenon is under discussion across multiple disciplines and subdisciplines, each of which has labeling practices that give salience to particular topics related to this phenomenon. Take for instance the topic of migration, which is studied not only in “migration studies,” but also in political science, sociology, economics, and anthropology. Each of these fields not only prioritizes particular methodologies, but also foregrounds certain issues in relation to migration, such as political, sociological, economic, or sociocultural issues. Participation in these fields comes with an expectation that scholarship will not only theorize a topic of interest such as migration, but also contribute to the theorization of intersecting issues within that field.

The fact that the same phenomenon can be discussed simultaneously across multiple fields points to the porous nature of disciplinary boundaries. That is, disciplines do not operate as discrete entities that investigate separate or separable issues, but rather, they use different tools to investigate similar objects and phenomena that have considerable overlap (see Mannheim 2018). As such, disciplines are better understood as different ways of organizing data and analysis around particular topical concerns, rather than as bounded areas of study. The differentiating factor between disciplines and subdisciplines, then, is in the attribution of topical salience (cf., Agha 2007a; Karimzad 2020) or the decision about what to foreground or make central in scholarship within the field. The attribution of topical salience defines not only academic study, but also how non-discrete information is divided up more generally, (re)creating categories for identities, objects, and relations (see Irvine and Gal 2000). While any given category may appear to be stable, it is in fact the result of dynamic categorization processes (cf., De Fina 2011), which are precisely defined by the organization of data in relation to what receives topical salience. Such categorization is simultaneously an unavoidable fact of social life and a “double-edged sword”: Categories enable an understanding of the world because of how they facilitate an organization of the varied and diverse pieces of information people encounter, but they also restrict understanding because they predispose people to recognizing familiar configurations of information and limit attention to what is considered to be “relevant” to the topic at hand (see Mayes and Tao 2019). The limitations imposed by categories can be countered, not by getting rid of them (see Gal 2018), but by developing a reflexive and “meta” understanding of how they are constructed and utilized in scholarship and in the social world more broadly (see Silverstein 1981; Urban 2018). Such a reflexive or meta-approach allows one to see the process of creating categories as not only unavoidable but also valuable in defining focus within and across interactions, reflections, and argumentations.

Coming up with a research focus involves similar meta-processes of categorization and in many ways resembles the processes through which an academic discipline is defined, albeit at a relatively smaller scale. Just as academic disciplines are defined through the repeated attribution of prominence to a particular set of issues, so a research question defines the scope of a research project by proposing to give prominence to some subset of issues in one’s investigation. By organizing information around what has been determined to be topically salient, a research question allows the analyst to engage in categorization processes, which can both limit and expand their potential for understanding the issues at hand. In order to make the best use of research questions then, it is necessary to engage them in flexible, dynamic, and reflexive ways. In this chapter, we lay out a system within which such engagement can be situated: In this system one can zoom in on a particular topic to investigate and describe its details and zoom out to highlight and explain its connections to a broader range of phenomena, much in the way that one can zoom in and out on a high-resolution image to focus on one particular aspect or to see the picture as a whole (cf., Karimzad 2021; Karimzad and Catedral 2021; see also Pritzker and Perrino 2020). This approach also makes it possible to put one’s research question in dialogue with other interrelated questions, categorizations, and conversations in ways that allow for the research focus to be expanded, restricted, modified, and changed.

Returning to the discussion of disciplinary boundaries, we also want to stress that from this perspective, there are no “off-limit” topics about which one can pose research questions. This is particularly true for linguistic anthropologists and sociolinguists, who study language use in the social world—a phenomenon that is involved in every aspect of human life (see Blommaert 2018; Silverstein 1981). Another way of putting this is that because discourse is the means through which categorization happens, any study of categories—whether aimed at challenging or utilizing them—is a study of discourse in its interactional, historical, political, and sociocultural contexts (see Foucault 1972; Jørgensen and Phillips 2002). The fact that any phenomenon can be the object of focus and the topic around which data are organized does not mean that the process of coming up with a research question is perfunctory or that it does not matter. Conversely, one makes their research matter precisely by choosing, articulating, and justifying this focus. Making research matter is admittedly a complex issue that is defined in relation to a wide range of personal, institutional, moral, and scientific values and value systems. Nonetheless, it is a process in which all researchers are engaged inasmuch as they confer importance to a topic by focusing their investigation on it and justify its importance through a demonstration of how it is in dialogue with the work of others.

1.2 Navigating and Situating Research Topics

1.2.1 A Fractal System of Knowledge Production

We find it useful to discuss knowledge production in terms of “presupposition” and “entailment” (Silverstein 1992): the construction of meaning involves presupposing some existing knowledge and categories, which allow for the entailment—or the creation—of new meanings and categories. Although this is a more general process at work in the social world, it also applies specifically to the production of academic knowledge. Scholars enter a research process with certain assumptions based on existing knowledge, which then allow them to categorize and understand their data, and their research projects as a whole, in particular ways, leading to the production of new knowledge.

In linguistic anthropology in particular, knowledge production is situated on the pragmatics-metapragmatics nexus as it plays out in the social world (Silverstein 1993). That is, the empirical, analytical, and theoretical focus of linguistic anthropological research is on social actors’ language practices—a matter of pragmatics—and their interaction with the ideologies that mediate these practices—that is, metapragmatics. Importantly, “language” here is understood in terms of semiosis, which is the construction and construal of meaning through both linguistic and nonlinguistic signs. To be precise, semiosis or meaning-making is made possible through indexical processes in which (non)linguistic signs point to, or index, their presupposed or potential contexts of use and call upon histories of their meaningful usage. It is metapragmatics that mediates the indexical linkages of linguistic signs and their contexts of use, providing those involved in social interaction with some idea for producing and interpreting semiotic practices in relation to particular contexts (Agha 2007b; Silverstein 1993; see also Blommaert 2018; Moore 2020). Those scholars interested in semiosis at the pragmatic-metapragmatic nexus understand that the interaction between pragmatics and metapragmatics is an everyday process through which speakers, including researchers, negotiate and evaluate meaning. However, when linguistic anthropologists theorize the metapragmatics of (meta)semiosis, they are working as meta-interpreters who operate at a higher-order position above the contexts from and about which these acts are situated. Thus, the production of knowledge in linguistic anthropology is a matter of meta-metapragmatics: Scholars use ethnographic data to investigate and theorize language use as well as ideological–normative reflections on this language use, and they then draw on and/or create meta-categories and meta-discourses, which organize these data and analyses in relation to research questions and topical concerns.

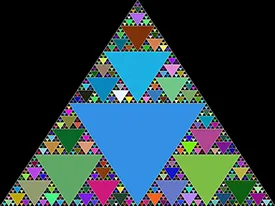

Situating oneself in a meta-position allows for an imagination of research topics and questions within a fractal system, where objects, phenomena, and relations are linked across various interconnected scale levels (cf., Blommaert and De Fina 2017; Gal 2016; Irvine and Gal 2000; Karimzad 2021). The four images in Figure 1.1 are illustrations of fractality: the first is an image of fractal triangles, the second a branch of a tree, and the third and fourth a Romanesco cauliflower (also called Romanesco broccoli) from a zoomed-out and zoomed-in point of view, respectively.

Figure 1.1 Fractal patterns1

While these images differ from one another in a number of ways, they are connected through their fractal patterns, that is, the recurrence of shapes or configurations at various scale levels, ranging from the microscopic to the macroscopic. Take the Romanesco cauliflower for instance: it is made up of pyramid-esque nodes, and each of these nodes is composed of smaller, similarly shaped nodes. The more zoomed-out image of the cauliflower makes it difficult to see all these fractal details and a viewer may miss the fact that each of the nodes is made up of smaller ones. The more zoomed-in image illuminates these details but may not give the whole picture of the cauliflower. If we look at the other images, we see that they differ in appearance from the cauliflower. Nonetheless, across these photos there is a similar way that recursive processes create patterns in which zooming in or out reveals repetitive fractal details and the interconnectedness of the structures as a whole. These structures are not merely the sum of individual parts or even of particular patterns, but rather more comprehensive and collective wholes. At the same time, the structures in these images are only approximations of fractals in the sense that their recursions end at some point, whereas within a fractal system such as the one we are imagining, one could zoom in or out infinitely and the fractal recursions would continue in any direction.

What we are discussing here applies specifically to knowledge production in that knowledge emerges from and in relation to a fractal system of interconnected and recursively organized information on which scholars can zoom in or out in their research processes. Such a system allows for reflection on research from multiple scalar positions (see Blommaert 2015, 2020; Canagarajah and De Costa 2016; Carr and Lempert 2016; Catedral 2018; Gal 2016). This, in turn, enables the possibility of moving away from, without doing away with, the categories that are used to define disciplinary- or project-specific focuses. This is because one can attend to a scalar level at which certain categories become relevant, or zoom in to consider a level at which these categories no longer matter as much as the microscopic social-semiotic details and nuances, or zoom out and consider a level at which the discrete nature of these categories is less relevant than the interconnectedness between them (see Karimzad 2021). To illustrate this further, let us return to the above images, but this time from the perspective of categories and categorization. While one might categorize and label what appears in the images as “triangles,” “foliage,” and “cauliflowers,” limiting the possibility of observing connections between these images, a more zoomed-out perspective makes these particular categories less relevant and could instead emphasize the interconnectedness of “cauliflower” and “foliage” through a broader category such as “plants” or, as we have done, emphasize the nature of fractality in order to illuminate connections between all four images.

Moving across these multiple levels not only facilitates a flexible engagement with categories but also allows researchers to imagine their research topics and questions as multi-scalar, interconnected, epistemological objects. This does not mean, however, that a researcher needs to, or can, engage the entire fractal system. The important point is that although everything is interconnected within the system as a whole, scholars can enter the discussion at any particular scale level. Using questions and topics in ways that enable rather than restrict research, then, requires a navigation of this system, and a commitment to situating a focus at particular scale levels—and on the categories associated with those scales—within the larger interconnected system, in order to determine where new knowledge is being contributed to the ongoing discussions.

This ability to understand and navigate the fractal system is useful in relation to multiple practical concerns at various stages in the research process and in relation to different projects across one’s research trajectory. As one example, take the fact that a young scholar who is starting their very first research project is likely to receive feedback in which they are told that their focus is too broad and that they need to make their research questions more specific. Alternatively, a scholar who is seeking funding for a research project may be asked to expand their view of their research focus and to explain why the issue matters at a broader level. These contrasting examples demonstrate that researchers ...