![]()

Old Herbaceous

by

Reginald Arkell

The mists be on the river bed,

The roses all be gone;

And here be I, about to die,

With Harvest coming on.

Dear Lord, I've traipsed some weary miles,

I'll be main glad to rest awhiles.

The folk'll soon be in the fields

A-getting in the grain;

For most of those, the time You've chose

Be awkerd in the main.

Though not so bad, 'tis sure, for they

As be a-workin' by the day.

September be a better month

For all the carter men;

And when I die don't signify,

So let I bide till then:

The wagons'll be standing by,

And there'll be time to bury I.

(From Green Fingers Again)

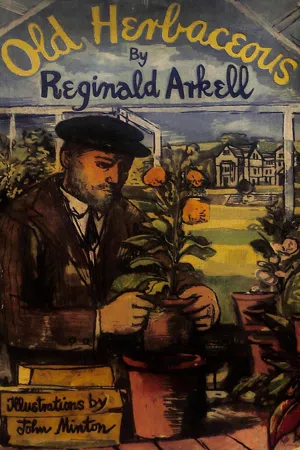

These young fellows should have seen him in the hour of his glory

[Pg 7]

It was one of those mild autumn mornings when early mist had turned to soft rain and water dripped from everything. No real touch of winter yet; just a soft pause between the seasons, giving you the best of both. Not too warm, as it had been; not too cold, as it would be. . . .

This was the time of year and the time of day that the old man loved best. He couldn't get around so much now, but they had made up his bed by the cottage window, and there he would sit, half waking and half sleeping, dreaming of this and that.

From where he sat, propped up among his cushions, he could see into the Manor gardens. Not what they were—not by a long chalk. . . . Mind you, it was only fair to admit they were still a bit short-handed, and you had to take the dry summer into account, but these young fellows ought to have made a better job of it than that. . . . When he was a young chap, he had to move at double their pace. No slipping off when the clock struck for him. Hours he'd spent watering when the sun was off the borders. . . . But not to-day. That meant overtime, and where was the money to pay for that? So the old garden wasn't what it had been when he was in charge.

Everything was different to what it was in his day. They [Pg 8]earned more money, and that was only right. But the more they got, the less they seemed to care. You had to be proud of a garden to do any good with it. Gardening was a whole-time job, like the cows or the sheep. Cows had to be milked, whatever happened; and who thought of stopping in bed when the sheep were lambing? In a garden, you had to work with the seasons. There were slack times, when you could take an easy with a pipe behind the tool shed, but when the grass started growing and the weeds were getting on top of you, there was an end to all that nonsense. . . . Hours he'd spent watering. . . . But these young fellows. . . .

That was the trouble nowadays. Nobody seemed to care any more. When he was a boy, you'd see the farm chaps and their families walking round in their Sunday clothes as though the place belonged to them. Showing off, they were. Proud of the work they'd done during the week. Laughing at young Harry's crooked furrows. Scuffling up a bit of spring wheat to see how it was doing. Cowman bragging to his missus about his herd. Shepherd making sure there wasn't a sheep on its back. . . . Then, if the farmer came along, they'd all have a friendly chat and everyone would learn something. . . . Good days, those were. . . . Good days.

Same with the garden. When he was in charge across the way, he never felt that he was just a paid man working for a wage. He felt that the place was his—and so it was, in a manner of speaking. He learned that from old John Addis, his first head gardener. Very quiet, old John was—very quiet and respectful, up to a point; but when it came to an argy-bargy with the young missus, there was no doubt who was boss. 'Very well, Addis,' she would say, 'if you think that's how it should be done, I've no objection.' And when it came to picking flowers for the house, they always [Pg 9]had to ask old John about it. . . . But not to-day. . . . Anyone could pick anything, because nobody cared any more. . . .

Looking out of his little window, the old man saw that the early morning mist had cleared, as though a gauze curtain had been raised to reveal the bright detail of a theatrical scene. The dahlias, not yet blackened by the first frost; michaelmas daisies and petunias, still making splashes of colour against a grey wall; the berries of a cotoneaster looking like a regiment of toy soldiers in ceremonial uniform. . . .

In the shrubberies, the yellowing nut bushes gave the first hint of autumn's final golden cavalcade. Very soon, the flowering shrubs would add their reds and oranges to the picture; coral berries would glisten behind the gothic foliage of the spindle trees and the great leaves of the catalpa would trace their crazy pattern on the wet grass. There would be the final flurry of butterflies round the last bit of buddleia. . . .

Truly a gracious and very English scene, as he had known it for more than three-quarters of a century. People said that big gardens were finished; that everything belonged to everybody and nothing to anybody. He didn't believe that. The world started with a garden and a thing that had been going all that time wouldn't end so easily. Anyway, they would last out his time and what happened after he'd gone wasn't his business.

Gardens! The old man closed his eyes and let his thoughts wander through the scented past. A long journey, up-hill most of the way, but it had led somewhere, and no mistake. . . . Started as a nobody and ended as a somebody. . . . That day when he was asked to judge at the County Show. . . . Lunch in the big marquee, and him sitting up at the top table. . . . Those were the days. . . . A young fellow could [Pg 10]push his way through and rise to anything. . . . If he wasn't afraid of work and took an interest in his job.

Well, he'd stuck to it, and he'd come out at the top. Respected, he was. They might laugh at him behind his back, some of the young ones. Called him 'Old Herbaceous' when they thought he wasn't listening. But they never took liberties. After all, he was a bit of a perennial. . . . Eighty years he'd been going. . . . . So let them have their little joke. . . .

That was the best of growing old. You didn't get hot under the collar about little things and you didn't have to worry about the future. . . . Time was too short for that. . . . Here he was, living in his own cottage and enough in the Post Office to see him through. . . . Anything he had he could pay for. . . . He wasn't dependent on one of them. . . . What they did for him they got paid for, and very glad they were to find the money on the corner of the mantelpiece every Saturday morning. . . .

That was the right way for a man to finish, and that was how it was going to be. . . .

[Pg 11]

On a certain Thursday in November 1789 was effected what the Morning Post described as 'the greatest object of internal Navigation in this Kingdom.' The Severn was united to the Thames by an intermediate canal, ascending to the height of 343 feet, by 40 locks; there entering a tunnel through the hill of Saperton, for the length of two miles and three furlongs, and descending by 27 locks to join the Thames near Lechlade.

When the first boat completed this tremendous journey, she was welcomed by vast crowds who answered a salute of twelve pieces of cannon by loud huzzas. A dinner was given at five of the principal Inns, and the day ended with ringing of bells, a bonfire and a ball.

'With respect to the internal commerce of the kingdom and the security of communication in time of war,' concluded the Morning Post, 'this junction of the Thames and Severn must, for all time, be attended with the most beneficial consequences.'

So much for the vanity of human prognostications. Within fifty years the railways had sealed the fate of inland water transport, and, in another fifty, the Thames and Severn canal was as near derelict as made no difference . . .

[Pg 12] But no depressing reflections on mutability and decay troubled the minds of the small country boys who, in the 'seventies, perched on the hump-backed bridge and exchanged dubious courtesies with the ageing lock-keeper who lived in the curious little Roundhouse. His job was almost a sinecure, for though the canal was still officially navigable, a week might pass before the next barge came through. And then it would only bring a load of coal for the villages or pick up sacks of barley sold by some local farmer to the brewers at Bristol.

So the lock-keeper, a contraptious old buffer, if ever there was one, had time enough to battle with his young tormentors and the canal settled down to the nostalgic task of forgetting its former glories.

Among the urchins who picked stones from the bridge and threw them into the stagnant water was one who did not enter largely into the spirit of the thing. Like his companions, he wore the discarded corduroys and hob-nailed boots of his seniors, but his features had a finer line, and one of his scraggy little legs was a shade shorter than the other; the result of rough horse-play in which he had had the worst of the bargain. His 'back answers' to the contraptious old buffer lacked the snap of his fellows; possibly because he couldn't run as fast as they could; and even when the occasional barge crawled round the corner of the canal, he was more concerned with the yellow flags and ragged robins that, each year, encroached more and more upon this dwindling waterway.

At this point in his ruminations, Old Herbaceous stirred uneasily among his cushions. He loved wandering in the past, especially along the banks of the old canal, but always the picture of himself, so different from the other boys, came [Pg 13]as a disturbing element. For different he had certainly been and for a very good reason.

Opening her cottage door, on a May morning some eighty-odd years ago, Mrs. Pinnegar, the cowman's wife, had received a shock, and no mistake. There, on the door-step, wrapped in an old cotton skirt, was a baby, as newly-born as made no difference. Mrs. Pinnegar, a kindly soul, with six children of her own, passed the village maidens in review. Several of them were 'expecting,' but Mrs. Pinnegar, unofficial midwife and friend of all families, knew their dates to a nicety and the problem was not so easily solved. There had been no gipsies through the village for weeks. . . . Being a practical woman, the cowman's wife picked up the parcel the fairies had brought her; christened it Herbert, after an uncle who was killed in the Crimea, and set about her Monday's wash. When you had six of your own, one more didn't matter.

Naturally, there was a bit of chatter at the time, but unexpected arrivals never made front-page news in an English village. A rick fire and talk of the Prussians in Paris were much more exciting. Young Herbert settled down in his new home; seasons came and went; the new self-binder started tying the sheaves with string . . .

Still, being picked up on a door-step did take the gilt off the gingerbread a bit; especially when you'd got along in the world and become someone in the village. True, there was nobody left to throw his birth in his teeth. Everybody was dead—every man Jack of them! Old folk went and new folk came, until you couldn't find a single soul who remembered anything. Very soon he'd go, too, and then there'd be nothing left but houses—and gardens.

Funny, that! You planted a tree; you watched it grow; you picked the fruit and, when you were old, you sat in the [Pg 14]shade of it. Then you died and they forgot all about you—just as though you had never been. . . . But the tree went on growing, and everybody took it for granted. It always had been there and it always would be there. . . . Everybody ought to plant a tree, sometime or another—if only to keep th...