- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

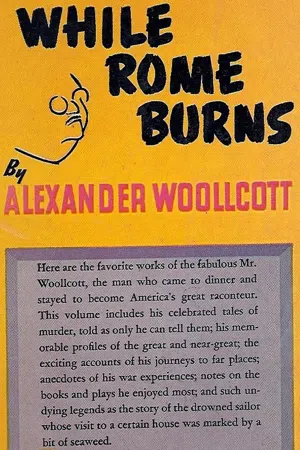

While Rome Burns

About this book

"This is Woollcott speaking."...America's favorite raconteur here offers a generous selection of his best horror stories, anecdotes, personal portraits, legendary tales and reminiscences, including celebrated tales of murder as only he could tell them, his memorable profiles of the great and near-great, the exciting accounts of his journeys to far places, his war experiences, and much more.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PORTRAIT of a poet attempted

by one who, abashed by the

difficulties of the undertaking,

breaks down and weakly resorts

to a hundred familiar quotations.

SOME NEIGHBORS: IV OUR MRS. PARKER

SOME NEIGHBORS: IV—OUR MRS. PARKER

When William Allen White, Jr., son of Emporia’s pride, was a verdant freshman ten years ago, he spent the Christmas vacation in New York and was naturally assumed as a public charge by all his father’s friends in the newspaper business. He had been at Harvard only a few months, but the pure Kansas of his speech was already seriously affected. He fastidiously avoided anything so simple as a simple declarative.

For example, he would never indulge in the crude directness of saying an actress was an actress. No, she was by way of being an actress. You see, they were going in for that expression at Harvard just then. Nor could he bring himself to ask outright if such and such a building was the Hippodrome. No, indeed. Subjunctive to the last, he preferred to ask, “And that, sir, would be the Hippodrome?”

I myself took him to the smartest restaurant of the moment, filled him to the brim with costly groceries, and escorted him to a first night. As we loped up the aisle during the intermission rush for a dash of nicotine, I pointed out celebrities in the manner of a barker on a Chinatown bus. Young Bill seemed especially interested in the seamy lineaments of a fellow Harvard man named Robert Benchley, then, as now, functioning on what might be called the lunatic fringe of dramatic criticism. Seated beside him was a little and extraordinarily pretty woman with dark hair, a gentle, apologetic smile, and great reproachful eyes. “And that, I suppose,” said the lad from Emporia, “would be Mrs. Benchley.” “So I have always understood,” I replied crossly, “but it is Mrs. Parker.”

In the first part of this reply, I was in error. At the time I had not been one of their neighbors long enough to realize that, in addition to such formidable obstacles as Mrs. Benchley, Mr. Parker, and the laws of the commonwealth, there was also a lack of romantic content in what was then, and ever since has been, a literary partnership seemingly indissoluble. At least it has had a good run. Mrs. Parker’s latest and finest volume of poems carries on the fly-leaf the simple dedication: “To Mr. Benchley,” and even a dozen years ago, these two shared a microscopic office in the crumby old building which still houses the Metropolitan Opera.

There was just about room in it for their two typewriters, their two chairs, and a guest chair. When both were supposed to be at work, merely having the other one there to talk to provided a splendid excuse for not working at all. But when Benchley would be off on some mischief of his own, the guest chair became a problem. If it stood empty, Mrs. Parker would be alone with her thoughts and—good God!—might actually have to put some of them down on paper. And, as her desperate editors and publishers will tell you, there has been, since O. Henry’s last carouse, no American writer so deeply averse to doing some actual writing. That empty guest chair afflicted her because the Parker-Benchley office was then so new a hideaway that not many of their friends had yet found a path to it, and even Mrs. Parker, having conscientiously chosen an obscure cubby-hole so that she might not be disturbed in her wrestling with belles-lettres, was becomingly reluctant to telephone around and suggest that everyone please hurry over and disturb her at once.

However, this irksome solitude did not last long. It was when the sign painter arrived to letter the names of these new tenants on the glass door that she hit upon a device which immediately assured her a steady stream of visitors, and gave her the agreeable illusion of presiding over as thronged a salon as even Madame Récamier knew. She merely bribed the sign painter to leave their names off the door entirely and print there instead the single word “Gentlemen.”

Thus pleasantly distracted through the years, Mrs. Parker’s published work does not bulk large. But most of it has been pure gold and the five winnowed volumes on her shelf—three of poetry, two of prose—are so potent a distillation of nectar and wormwood, of ambrosia and deadly nightshade, as might suggest to the rest of us that we all write far too much. Even though I am one who does not profess to be privy to the intentions of posterity, I do suspect that another generation will not share the confusion into which Mrs. Parker’s poetry throws so many of her contemporaries, who, seeing that much of it is witty, dismiss it patronizingly as “light” verse, and do not see that some of it is thrilling poetry of a piercing and rueful beauty.

I think it not unlikely that the best of it will be conned a hundred years from now. If so, I can foresee the plight of some undergraduate in those days being maddened by an assignment to write a theme on what manner of woman this dead and gone Dorothy Parker really was. Was she a real woman at all? he will naturally want to know. And even if summoned from our tombs, we will not be sure how we should answer that question.

Indeed, I do not envy him his assignment, and in a sudden spasm of sympathy for him, herewith submit a few miscellaneous notes, though, mark you, he will rake these yellowing files in vain for any report on her most salient aspects. Being averse to painting the lily, I would scarcely attempt a complete likeness of Mrs. Parker when there is in existence, and open to the public, an incomparable portrait of her done by herself. From the nine matchless stanzas of “The Dark Girl’s Rhyme”—one of them runs:

There I was, that came of

Folk of mud and flame—

I that had my name of

Them without a name—

to the mulish lyric which ends thus:

But I, despite expert advice,

Keep doing things I think are nice,

And though to good I never come—

Inseparable my nose and thumb!

her every lyric line is autobiographical.

From the verses in Enough Rope, Sunset Gun, and Death and Taxes, the toiling student of the year 2033 will be able to gather, unaided by me, that she was, for instance, one who thought often and enthusiastically of death, and one whose most frequently and most intensely felt emotion was the pang of unrequited love. From the verses alone he might even construct, as the paleontologist constructs a dinosaur, a picture of our Mrs. Parker wringing her hands at sundown beside an open grave and looking pensively into the middle-distance at the receding figure of some golden lad—perhaps some personable longshoreman—disappearing over the hill with a doxy on his arm.

Our Twenty-First Century student may possibly be moved to say of her, deplorably enough, that, like Patience, our Mrs. Parker yearned her living, and he may even be astute enough to guess that the moment the aforesaid golden lad wrecked her favorite pose by showing some sign of interest, it would be the turn of the sorrowing lady herself to disappear in the other direction just as fast as she could travel. To this shrewd guess, I can only add for his information that it would be characteristic of the sorrowing lady to stoop first by that waiting grave, and with her finger trace her own epitaph: “Excuse my dust.”

But if I may not here intrude upon the semi-privacy of Mrs. Parker’s lyric lamentation, I can at least supply some of the data of her outward life and tell the hypothetical student how she appeared to a neighbor who has often passed the time of day with her across the garden wall and occasionally run into her at parties. Well, then, Dorothy Parker (née Rothschild) was born of a Scotch mother and a Jewish father. Her people were New Yorkers, but when she came into the world in August 1893, it was, to their considerable surprise and annoyance, a trifle ahead of schedule. It happened while they were staying at West End, which lies on the Jersey shore a pebble’s throw from Long Branch, and it was the last time in her life when she wasn’t late.

Her mother died when she was still a baby. On the general theory that it was a good school for manners, she was sent in time to a convent in New York, from which she was eventually packed off home by an indignant Mother Superior who took umbrage when her seemingly meek charge, in writing an essay on the miracle of the Immaculate Conception, referred to that sacred mystery as spontaneous combustion. When, at her father’s death a few years later, she found herself penniless, she tried her hand at occasional verse, and both hands at playing the piano for a dancing school.

Then she got a job writing captions on a fashion magazine. She would write “Brevity is the Soul of Lingerie” and things like that for ten dollars a week. As her room and breakfast cost eight dollars, that left an inconsiderable margin for the other meals, to say nothing of manicures, dentistry, gloves, furs, and traveling expenses. But just before hers could turn into an indignant O. Henry story, with General Kitchener’s grieving picture turned to the wall and a porcine seducer waiting in the hall below, that old marplot, her employer, doubled her salary. In 1918, she was married to the late Edwin Parker, a Connecticut boy she had known all her life. She became Mrs. Parker a week before his division sailed for France. There were no children born of this marriage.

Shortly after the armistice, the waiting bride was made dramatic critic of Vanity Fair, from which post she was forcibly removed upon the bitter complaints of sundry wounded people of the theater, of whose shrieks, if memory serves, Billie Burke’s were the most penetrating. In protest against her suppression, and perhaps in dismay at the prospect of losing her company, her coworkers, Robert E. Sherwood and Robert Benchley, quit Vanity Fair at the same time in what is technically known as a body, the former to become editor of Life, and the latter its dramatic critic.

Since then Mrs. Parker has gone back to the aisle seats only when Mr. Benchley was out of town and someone was needed to substitute for him. It would be her idea of her duty to catch up the torch as it fell from his hand—and burn someone with it. I shall never forget the expression on the face of the manager who, having recklessly produced a play of Channing Pollock’s called The House Beautiful, turned hopefully to Benchley’s next feuilleton, rather counting on a kindly and even quotable tribute from that amiable creature. But it seems Benchley was away that week, and it was little Mrs. Parker who had covered the opening. I would not care to say what she had covered it with. The trick was done in a single sentence. “The House Beautiful,” she had said with simple dignity, “is the play lousy.”

And more recently she achieved an equal compression in reporting on The Lake. Miss Hepburn, it seems, had run the whole gamut from A to B.

But for the most part, Mrs. Parker writes only when she feels like it or, rather, when she cannot think up a reason not to. Thus once I found her in hospital typing away lugubriously. She had given her address as Bed-pan Alley, and represented herself as writing her way out. There was the hospital bill to pay before she dared get well, and downtown an unpaid hotel bill was malignantly lying in wait for her. Indeed, at the preceding Yuletide, while the rest of us were all hanging up our stockings, she had contented herself with hanging up the hotel.

Tiptoeing now down the hospital corridor, I found her hard at work. Because of posterity and her creditors, I was loath to intrude, but she, being entranced at any interruption, greeted me from her cot of pain, waved me to a chair, offered me a cigarette, and rang a bell. I wondered if this could possibly be for drinks. “No,” she said sadly, “it is supposed to fetch the night nurse, so I ring it whenever I want an hour of uninterrupted privacy.”

Thus, by the pinch of want, are extracted from her the poems, the stories, and criticisms which have delighted everyone except those about whom they were written. There was, at one time, much talk of a novel to be called, I think, The Events Leading Up to the Tragedy, and indeed her publisher, having made a visit of investigation to the villa where she was staying at Antibes, reported happily that she had a great stack of manuscript already finished. He did say she was shy about letting him see it. This was because that stack of alleged manuscript consisted largely of undestroyed carbons of old articles of hers, padded out with letters from her many friends.

Then she once wrote a play with Elmer Rice. It was called Close Harmony, and thanks to a number of circumstances over most of which she had no control, it ran only four weeks. On the fourth Wednesday she wired Benchley: “CLOSE HARMONY DID A COOL NINETY DOLLARS AT THE MATINEE STOP ASK THE BOYS IN THE BACK ROOM WHAT THEY WILL HAVE.”

The outward social manner of Dorothy Parker is one calculated to confuse the unwary and unnerve even those most addicted to the incomparable boon of her company. You see, she is so odd a blend of Little Nell and Lady Macbeth. It is not so much the familiar phenomenon of a hand of steel in a velvet glove as a lacy sleeve with a bottle of vitriol concealed in its folds. She has the gentlest, most disarming demeanor of anyone I know. Don’t you remember sweet Alice, Ben Bolt? Sweet Alice wept with delight, as I recall, when you gave her a smile, and if memory serves, trembled with fear at your frown. Well, compared with Dorothy Parker, Sweet Alice was a roughshod bully, trampling down all opposition. But Mrs. Parker carries—as everyone is uneasily aware—a dirk which knows no brother and mighty few sisters. “I was so terribly glad to see you,” she murmurs to a departing guest. “Do let me call you up sometime, won’t you, please?” And adds, when this dear chum is out of hearing, “That woman speaks eighteen languages, and can’t say No in any of them.” Then I remember her comment on one friend who had lamed herself while in London. It was Mrs. Parker who voiced the suspicion that this poor lady had injured herself while sliding down a barrister. And there was that wholesale libel on a Yale prom. If all the girls attending it were laid end to end, Mrs. Parker said, she wouldn’t be at all surprised.

Mostly, as I now recall these cases of simple assault, they have been muttered out of the corner of her mouth while, to the onlooker out of hearing, she seemed all smiles and loving-kindness. For as she herself has said (when not quite up to par), a girl’s best friend is her mutter. Thus I remember one dreadful week-end we spent at Nellie’s country home. Mrs. Parker radiated throughout the visit an impression of humble gratitude at the privilege of having been asked. The other guests were all of the kind who wear soiled batik and bathe infrequently, if ever. I could not help wondering how Nellie managed to round them up, and where they might be found at other times. Mrs. Parker looked at them pensively. “I think,” she whispered, “that they crawl back into the woodwork.”

Next morning we inspected nervously the somewhat inadequate facilities for washing. These consisted of a single chipped basin internally decorated with long-accumulated evidences of previous use. It stood on a bench on the back porch with something that had apparently been designed as a toothbrush hanging on a nail above it. “In God’s name,” I cried, “what do you suppose Nellie does with that?” Mrs. Parker studied it with mingled curiosity and distaste, and said: “I think she rides on it on Halloween.”

It will be noted, I am afraid, that Mrs. Parker specializes in what is known as the dirty crack. If it seems so, it may well be because disparagement is easiest to remember, and the fault therefore, if fault there be, lies in those of us who—and who does not?—repeat her sayings. But it is quite true that in her writing—at least in her prose pieces—her most effective vein is the vein of dispraise. Her best word portraits are dervish dances of sheer hate, equivalent in the satisfaction they give her to the waxen images which people in olden days fashioned of their enemies in ...

Table of contents

- IN THAT STATE OF LIFE

- THE SACRED GROVE

- A PLOT FOR MR. DREISER

- REUNION IN PARIS

- HANSOM IS

- HANDS ACROSS THE SEA

- MY FRIEND HARPO

- REUNION IN NEWARK

- FATHER DUFFY

- OBITUARY

- THE EDITOR’S EASY CHAIR

- FOR ALPHA DELTA PHI

- AUNT MARY’S DOCTOR

- THE TRUTH ABOUT JESSICA DERMOT

- LEGENDS: I ENTRANCE FEE

- LEGENDS: II MOONLIGHT SONATA

- LEGENDS: III FULL FATHOM FIVE

- LEGENDS: IV THE VANISHING LADY

- LEGENDS: V RIEN NE VA PLUS

- THE CENTURY OF PROGRESS: I THE LITTLE FOX-TERRIER

- THE CENTURY OF PROGRESS: II BELIEVE IT OR NOT

- SOME NEIGHBORS: I A PORTRAIT OF KATHLEEN NORRIS

- SOME NEIGHBORS: II COLOSSAL BRONZE

- SOME NEIGHBORS: III THE FIRST MRS. TANQUERAY

- SOME NEIGHBORS: IV OUR MRS. PARKER

- SOME NEIGHBORS: V THE MYSTERIES OF RUDOLFO

- SOME NEIGHBORS: VI THE LEGEND OF SLEEPLESS HOLLOW

- SOME NEIGHBORS: VII THE PRODIGAL FATHER

- SOME NEIGHBORS: VIII THE YOUNG MONK OF SIBERIA

- “IT MAY BE HUMAN GORE”: I BY THE RUDE BRIDGE

- “IT MAY BE HUMAN GORE”: II IN BEHALF OF AN ABSENTEE

- “IT MAY BE HUMAN GORE”: III THE MYSTERY OF THE HANSOM CAB

- “IT MAY BE HUMAN GORE”: IV LA BELLE HÉLÈNE AND MR. B.

- “IT MAY BE HUMAN GORE”: V MURDER FOR PUBLICITY

- YOUR CORRESPONDENT: I MOSCOW AN EXOTIC FIGURE IN MOSCOW

- YOUR CORRESPONDENT: I MOSCOW - THE CORPORAL OF ST.-AIGNAN

- YOUR CORRESPONDENT: I MOSCOW - COMRADE WOOLLCOTT GOES TO THE PLAY

- YOUR CORRESPONDENT: I MOSCOW - THE RETREAT FROM MOSCOW

- YOUR CORRESPONDENT: II GOING TO PIECES IN THE ORIENT

- YOUR CORRESPONDENT: III HOW TO GO TO JAPAN

- PROGRAM NOTES: I CHARLIE—AS EVER WAS

- PROGRAM NOTES: II CAMILLE AT YALE

- PROGRAM NOTES: III LEST WE FORGET

- PROGRAM NOTES: IV MOURNING BECOMES ELECTRA

- PROGRAM NOTES: V THIS THING CALLED THEY

- BOOK MARKERS: I THE GOOD LIFE

- BOOK MARKERS: II THE WIFE OF HENRY ADAMS

- BOOK MARKERS: III THE GENTLE JULIANS

- BOOK MARKERS: IV THE LAST OF FRANK HARRIS

- BOOK MARKERS: V THE NOSTRILS OF G.B.S.

- BOOK MARKERS: VI WISTERIA

- BOOK MARKERS: VII THE TRIUMPH OF NEWTIE COOTIE

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access While Rome Burns by Alexander Woollcott in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Literary Essays. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.