![]()

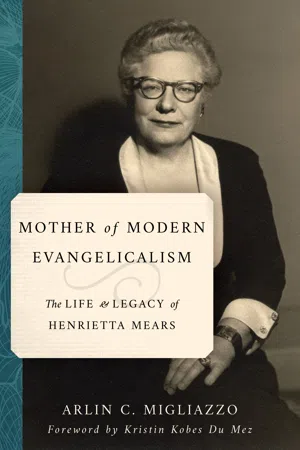

Chapter One

Bloodlines

In the quarter century that elapsed since Henrietta Mears assumed her duties as the director of Christian education at Hollywood’s First Presbyterian Church in 1928, she had become something of an international celebrity among a worldwide Protestant network of parishioners, pastors, missionaries, and teachers. Intent on sharing her story with an even broader audience during the tension-filled years of the Cold War, one of Mears’s younger devotees expressed an interest in writing her biography. Mears found the suggestion ludicrous: “Who wants to know the story of my life? I was born, I lived, I died! What’s so special about that? No one wants to read the story of my life.” A respected publisher, however, disagreed and in 1956 commissioned Barbara Hudson Powers to write the biography of her mentor. So began an ongoing series of discussions that took the young mother from her San Fernando Valley home to Henrietta Mears’s palatial estate in the Bel Air neighborhood west of Beverly Hills. Rain or shine, Powers packed her cumbersome seven-inch reel-to-reel tape recorder into the car and snaked along Coldwater Canyon to 110 Stone Canyon Road just across Sunset Boulevard from the UCLA campus. Once she had wrestled the tape recorder from the backseat into Mears’s home and switched it on, her subject regaled Powers with stories from her past shared previously with only a select few.

The faith and social activism of her mother and maternal grandmother figured conspicuously in her recollections, but Mears spent relatively little time reflecting on her father’s spiritual life except to note that his was a practical faith. When she did speak of him, her memories tended to emphasize his humor or the admission that as a child she could get whatever she wanted from him—a fact certainly not lost on her older siblings. She did not mention or explain his extensive absences from home. While she characterized her maternal relatives as profoundly spiritual, Mears depicted her father’s family as more materially oriented and socially connected; yet she also used the term “militant” (without explaining it) to describe her paternal grandmother’s Christian commitment, which other family members also shared. She recounted the loss of her family’s elite status in the wake of the economic downturn of the mid-1890s, but not the underlying reasons for that loss. Mears spoke freely of the role that physical ailments and death played in the strengthening of her faith, but she did not offer a similar interpretation regarding the many moves her family made during her formative years or the litigation that dogged them during those years. The stories Mears told Powers of abiding faith through good times and bad served as spiritual touchstones for her entire life. But so also did the more troubling aspects of Mears’s youth that never made it onto any of Powers’s tapes or into her 1957 biography. The interplay between the experiences Mears shared with Powers and those she kept to herself shaped her worldview and forged her character in ways that would have substantial consequences for the cause of theologically conservative American Protestantism.1

HENRIETTA CORNELIA’S BIRTH on October 23, 1890, in Fargo, North Dakota, completed the family of Elisha Ashley and Margaret Burtis Mears.2 The youngest of seven children and the third daughter, she grew to maturity in a loving family environment simultaneously permeated by piety and intrigue across four generations. Her father, born in Poultney, Vermont, in 1840, came from a family that sank its roots deep in the civic and religious life of the young republic. Elisha matured under three crucial influences: the Baptist faith of his parents, the commercial intricacies of the metals trade, and the care of a prosperous and privileged extended family. He had an uncanny ability to detect opportunities when they appeared and to seize them for personal gain. By his late teens Poultney could not ground his future nor fulfill his ambitions. Young Mears decided to look elsewhere.

He traveled west, settled in Chicago, and passed the Illinois state bar examination on his twenty-first birthday to become one of the youngest members of the Chicago Bar Association. Though now a lawyer, he utilized the knowledge and skills developed under his father Simeon’s tutelage to good benefit, facilitating his entrance into the nascent manufacturing and metals industries of the growing city. By autumn 1863 Elisha was doing well enough in the tinware business to have earned a listing on the excise tax rolls of the city. The following year he advertised himself as a stove manufacturer as well. He reportedly made a small fortune in metals trading during the Civil War, clearing $25,000 in one scrap iron transaction. By the final year of the war he had added copper, sheet iron, and holloware plus stamped and japanned ware to his inventory and established a foundry.3 While attending Chicago’s prestigious First Baptist Church, Elisha met Margaret Burtis Everts, daughter of the dynamic senior pastor of the church and his second wife—the two women who were to exert the greatest acknowledged influence on the life and ministry of Henrietta Mears.

Her maternal grandmother, Margaret Keen Burtis, grew up a faithful Philadelphia Baptist, but at fourteen had an intense religious conversion experience while participating in a series of meetings at a Presbyterian church close to her home.4 From that point forward Margaret committed herself to live out her Christian faith with a single-mindedness that transformed all aspects of her life. She shunned dancing and any clothing or ornamentation that might inhibit her ability to approach those with fewer material possessions. Money she saved went to assist others. On numerous occasions Margaret refused to accept gifts of clothing she deemed inappropriate. She began a journal, in the words of her biographer, because of a need for “vigilance and frequent self-examination.”5

Margaret became consumed with the desire to mature spiritually and to give evidence of her faith in practical ways. She often wrote of her unworthiness and God’s grace toward her. Among her earliest resolutions were those committing herself to attend all prayer meetings when possible, to spend constructive time with other Christians, and to work for the conversion of non-Christians, including members of her own family. Subsequent journal entries demonstrate the importance she placed on giving of her money and time to the needy and the absolute necessity of progressing in her Christian walk. On a monthlong visit to relatives in New Jersey one summer, she organized a Sunday school for local children. She also planned and taught an evening class for young women employed in her father’s factory.

Tragically, Margaret’s mother passed away soon after the sixteen-year-old entered the Collegiate Institution for Young Ladies. Bowing to her father’s wishes, she traded her educational aspirations for the responsibility of running the household. In 1836 she met young William Wallace Everts, a Baptist theology student from Hamilton, New York. The two married in 1843. Over the next sixteen years the Reverend Everts pastored churches in New York State and then in Louisville, Kentucky, with Margaret providing valuable professional assistance while raising their blended family, which ultimately included five children, two of whom had been born to Everts and his deceased first wife. In 1859, with sectional antagonism building ahead of the Civil War, he accepted an invitation to lead the First Baptist Church of Chicago where he blossomed into a popular and forceful religious leader over the ensuing twenty years.

In many aspects of his work Margaret joined him as a key contributor. She wrote her own musical compositions, taught Sunday school, provided music for church functions, and visited church members and friends on her husband’s behalf. She spoke and wrote on the importance of giving to church causes, appealing to the congregation for greater generosity on one final occasion the Sunday before her death in 1866. For the last fifteen years of her life, Margaret carried on nearly all Everts’s correspondence and transcribed thousands of pages destined for publication. During one of his absences, she “responded to a call for Christian direction from a gentleman of position and influence, and there for hours she met his speculations, inquiries, and agonized doubts, with prayer and the Bible,” acting essentially as a pastoral counselor. She worked alongside Everts in his support of the original University of Chicago, focusing on the needs of students. She ultimately became president of the Ladies Baptist Educational Society, which mobilized Baptist women throughout the state for this purpose.6

Never comfortable with the material trappings that came with a successful urban pastorate,7 Margaret continued to express a deep concern as well for the underserved outside Baptist circles. Soon after settling in Chicago she became a manager of the city’s Orphan Asylum and then of the Home for the Friendless. But she reserved her most passionate advocacy for women. She was a driving force behind the establishment of the first home for destitute females in the city. When the facility proved insufficient, Margaret and her small band of reformers found a larger location, which also filled quickly. Two years later, with the backing of some distinguished citizens, they secured an even bigger home and property, but need continued to exceed capacity. During the final summer of her life, Margaret joined others in soliciting funds from many sources, including the Chicago Common Council, for a seventy-five-bed expansion that included a hospital.

An evangelical ecumenism pervaded both Margaret’s and Rev. Everts’s sense of Christian service. While continuing their duties as committed Baptists, neither confined their interests or their efforts to Baptist circles or only those inside the greater Christian community. The need for justice and mercy meant justice for all and mercy to all. One church historian wrote of Margaret that she “devised, organized, and led in the execution of numerous systems of charity and benevolence, not only of this church, but in the wider circles of society, where all the various churches and creeds of the city were represented.”8 It was this expansive sense of Christian duty that their daughter Margaret Burtis Everts brought to her marriage with Elisha Mears and passed on to her children.

Exactly how and when Elisha and the younger Margaret met is unclear, although it is possible that their initial encounters occurred when she was barely into her teens. Soon after Elisha’s arrival in Chicago his parents and sisters relocated to the city. All attended the First Baptist Church together and Simeon joined Elisha in the hardware trade. Sometime between Elisha’s first visit to the church and his marriage to Margaret toward the end of the decade, he and Everts partnered in a speculative real estate development on the North Shore that would have significant consequences for the Mears family. The lure of quick success pulled his interests progressively away from manufacturing toward the financial services industry.9

Against the backdrop of complex transactions worth thousands of dollars and partnered with one of the most powerful men in Chicago, as well as one of the most influential Baptists in the country, Elisha courted Margaret. Little is known about the length of their relationship before their marriage and not much more about its nature, but it must have been quite complicated. After Margaret’s mother died, she spent much of the next two years studying music and the arts in Germany while Elisha remained in Chicago tending his hardware company and speculating in North Shore properties.10

By the fall of 1868 their intentions toward each other were clear. As the wedding approached, Margaret’s father, perhaps aware of either the expense or the impossibility of including all those dear to them, refused to have invitations sent, instead issuing an open invitation to the December 31, 1868, marriage ceremony directly from the pulpit. So many well-wishers attended that a contingent of Chicago mounted policemen facilitated crowd control. Shortly after their marriage and pregnant with her first child, Margaret returned to Europe for a time, probably to attend her father’s wedding in May 1869. In mid-June Elisha sent her some presents and wrote about the latest developments in his ongoing real estate transactions north of the city. By this time he had purchased at least one lakeshore lot as a potential summer home. Toward the end of the seven-page letter Elisha reflected on the pressures of the business world, hoping that she would guard him “against dissipation of any kind and never let me under any pretense take a glass of wine.”11

Over the course of the 1870s the Mears family grew with the addition of four more children. Members of the family not only spent time with their Everts relatives, they also regularly visited their Mears relations in Poultney, remaining firmly grounded in extended family connections that stretched from New England and Georgia to the Midwest. When Elisha suffered an unspecified misfortune in 1878, Margaret’s brother William tried but failed to find him a position in Providence, Rhode Island. Whatever occurred seems to have had a major impact on the family, for shortly after Norman’s birth, they left for New Jersey where a sixth sibling, Margaret, was born. While they may have moved eastward to be closer to Mears family members, the more probable cause lay in the fact that Margaret’s father accepted the call to serve Bergen Baptist Church in Jersey City in January 1879. By June 1880 Elisha, Margaret, and their children, along with Elisha’s sisters Elizabeth and Cornelia, all lived in Jersey City. Whether by design or default, Mears left hardware behind to pursue his interest in real estate development.12

Although Elisha’s profession is noted as real estate in the 1880 census, nothing is known about what that designation may have entailed or whether he sought advice from relatives in the industry at this pivotal point. It is also difficult to determine whether monetary or personal reverses or a lethal combination of both led the family to leave New Jersey. What is known is that oldest daughter Florence contracted typhoid fever and died on August 21, 1882. The effects of this first “Great Sorrow” as it was called by Elisha’s mother, washed over the entire extended household. Although their faith sustained them, Florence’s passing initiated a period of instability that would last well into the 1890s and test the Mears family in ways they could not then have imagined.13 Memories of a long deceased, similarly named sister intertwined with Elisha’s grief over the loss of his seven-year-old daughter. Within a year he cut his losses and turned his attention westward.14

Perhaps stimulated by the achievements of relatives in Saint Paul, Elisha moved his family in 1883 to the frontier settlement of Ipswich, Dakota Territory, where he became a prominent real estate developer. He quickly expanded his economic interests, purchasing properties nearby in Edmunds County and testing the mortgage sales market.15 Hoping to build upon these exploits, he moved his large family to Minot in 1887. Over the next two years he burnished both his financial position and his personal reputation, founding a number of banks and serving in a variety of civic positions. As his successes multiplied, so also did his ambition; neither Ipswich nor Minot could contain it. In October 1889, less than a month before North Dakota joined the union, Elisha relocated his family to Fargo in order to manage and diversify his rapidly growing empire from the largest city in the new state. That empire ultimately included nearly twenty businesses—unchartered territorial, state, and national banks, insurance firms, and at least one livestock company.16

From his initial days in Ipswich, Elisha took advantage of the economic climate of a region abundantly rich in natural resources, poor in capital, and lax in regulation. Banking protocols in the late nineteenth century encouraged “creative” practices—especially in the territories—and Elisha made the most of these conditions.17 Through an ingenious but precariously interlocked network of companies, Elisha wedded his aspirations to the intense desire for land ownership characteristic of settlers in the rural Midwest. He provided Dakota homesteaders with capital gleaned almost exclusively from eastern investors, often through contacts he reportedly made by attending church services and participating in charitable events during his regular and sometimes lengthy trips to the East.18

Elisha’s First National Bank of Fargo served as the crown jewel of a commercial domain that covered much of North Dakota. His Mortgage Bank and Investment Company, through which he managed all of his other i...