eBook - ePub

Leadership in Crisis

11 Leadership Lessons from the Global Pandemic

Rachel Feintzeig

This is a test

- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Leadership in Crisis

11 Leadership Lessons from the Global Pandemic

Rachel Feintzeig

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The Covid crisis has been a proving ground of sorts for business leaders, forcing them to adapt to new realities and unprecedented uncertainty. Leading through it has often been painful, but it's also produced valuable lessons about rallying employees, navigating global pressures, and finding opportunity amid hardship.

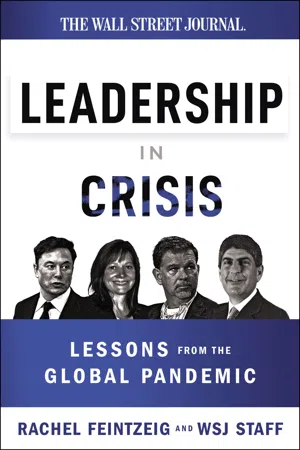

Leadership in Crisis profiles leaders of a range of business from auto giants like Telsa and General Motors to Moderna, the upstart that developed a Covid-19 vaccine, to a small grocery store in North Carolina. Takeaways include:

- Take advantage of a crisis to try something new.

- Channel your scrappiness and tenacity.

- Be of service.

Turn to Leadership in Crisis and remember that when the world breaks, there are all kinds of opportunities to make it better, for your business and beyond.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Leadership in Crisis by Rachel Feintzeig in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Leadership. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

THE STALWART

DAVID FARREMERSON ELECTRIC

The CEO of manufacturing giant Emerson Electric Co. for two decades, David Farr likes the corporate jet, golf, and vodka on the rocks. He’s known to poke his people with baseball bats during earnings calls if he thinks they’re doing a subpar job of talking to investors. The sight of empty parking lots—even at other companies—during much of 2020 made him mad. He didn’t serve in the military, but his approach to crises is distinctly militaristic. “I’m not going to die,” he said in the first weeks of the pandemic. “I’m too busy to die.”

He’s helped Emerson weather everything from the September 11 attacks to the 2014 protests following the shooting death of an unarmed Black teenager in Ferguson, Missouri, where the company is headquartered. But the pandemic proved the biggest challenge of his career, sprouting a host of roadblocks, from government regulations to logistics challenges, and upending many of the lessons of his years of experience. His moves in the face of obstacles around the globe are a fascinating case study in management.

Rachel’s Takeaways

- Never stop pushing forward. You might be wrong sometimes, but remember that a leader’s job is to make calls and take leaps.

- Realize you are a model and your employees may take their cues from you.

- Sometimes, you have to make your move and ask for forgiveness later.

The COVID Crisis Taught David Farr the Power and Limits of Leadership

Nine months with Emerson Electric, a manufacturing giant, show the firm knocked off course by the pandemic. The CEO insisted on moving forward anyway.

BY THOMAS GRYTA

DECEMBER 4, 2020

David Farr looked down at the empty parking lot and blew up. It was March 20, a cloudy day with a chill in the air. The coronavirus and lockdowns were grinding the US economy to a halt, sending much of the American workforce home, including most of those at the Ferguson, Missouri, headquarters of Emerson Electric Co.

Mr. Farr, who had run the industrial conglomerate for two decades, wasn’t going anywhere. He told his assistant to summon the other eight members of the OCE—the Office of the Chief Executive.

“We have a company to run,” he growled, his voice echoing through the empty sixth floor.

Mr. Farr wasn’t naive. The virus had torn through China and Europe, disrupting Emerson’s operations. It was just a matter of time before it spread in the US.

But World War II wasn’t won by hiding, he liked to tell people, and generals can’t lead their armies from the bunker. He expected employees to be present, and he wasn’t going to run the company from his home office.

“We have customers to serve and we can’t frickin’ do it if nobody is here!” he bellowed to the group assembled in his office.

COVID-19 has tested executives like few other events in modern history. How they respond is making some careers and breaking others.

In more than three dozen interviews throughout the course of the year, Mr. Farr and his top lieutenants showed what it’s like to guide a global enterprise without a map.

The CEO reveled in his firm control and belief in constant action. The pandemic rendered much of that experience irrelevant.

It sprouted crises for Emerson’s widespread global operations faster than Mr. Farr could contain them. He butted up against the reality of government regulations, suppliers struggling to meet commitments, and sick workers idling production.

Mr. Farr, center, leads an executive team meeting.

PHOTO: WHITNEY CURTIS FOR THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

For all his attention to detail, Mr. Farr knows he underestimated the threat. “Why did we miss it?” Mr. Farr, sixty-five years old, said last month. “I fault myself for that because I would have been better prepared.”

And yet he never stopped moving. Pushing through a crisis, with small and reversible steps, and making tough choices, such as pursuing an acquisition and pushing out a lieutenant, is better in his mind than waiting to act.

“I might be wrong, but we get paid to make decisions and make calls,” he said in April after he shared financial projections with Emerson’s board of directors. “I would never jump off a cliff without knowing a bit about what is at the bottom. But I know you have to take jumps.”

Seven Charter Planes

Emerson, with 90,000 employees around the globe, has roots in the nineteenth century, when it made the first electric fans sold in the US. Built up by acquisitions, it now produces cutting-edge systems that automate factory processes, and heating and air-conditioning equipment. It makes giant valves used in the oil industry as well as Insinkerator garbage disposals and the red Ridgid pipe wrenches used by generations of plumbers. It runs more than two hundred manufacturing sites, with two-thirds of them outside the US. To shareholders, it’s a business worth $45 billion.

On January 21, Mr. Farr was in Mumbai with five of his top executives when he opened an email from the head of Emerson’s China business, Jennie Li. She wanted to talk about a virus outbreak—and a possible government plan to lock down the sprawling city of Wuhan.

The company employed 8,000 people in China at three dozen facilities. Fewer than a thousand people were infected by the virus globally, and it was impossible to gauge where this would go.

Within days, China extended its Lunar New Year holiday to help slow the spread of the virus. Mr. Farr finished his trip to India and headed home, certain something big was brewing, even if its extent was unclear.

Back in Ferguson, Mr. Farr asked his chief operating officer, Steve Pelch, to put together a team to make sure they were doing everything they could to keep the China operations safe and running.

Mr. Farr knew that if China shut down, it could choke the company and the global economy. Production would slow as parts inventory thinned, orders would back up or be canceled, and the loss of scale and sales would make each transaction less profitable. The resulting slowdown could reshape industries as companies shrank and others—those smart enough to be ready—grabbed market share.

Emerson’s products were essential to keeping power and water utilities and other critical services running smoothly, even refrigeration for medicines and food. But now, a truck full of flow meters coming from its Nanjing factory and going to Shanghai was finding it almost impossible to get through.

The company reserved seven charter planes, ensuring it could get its products out of the country for months to come. It proved to be a lifeline when the cost of logistics skyrocketed.

This could all be managed, Mr. Farr thought. Seeing the Chinese government deal with the virus early in the year and reopen without major outbreaks gave him some confidence. “I got into a lot of heated battles around here in St. Louis because I had the opinion that you can live with this virus,” he said.

On February 4, Emerson reported first-quarter earnings. The coronavirus was mentioned nine times by executives on the conference call with Wall Street analysts. Mr. Farr expressed his concern for the Emerson workers in China. He predicted that the sales impact from virus disruption would be moderate but warned economic growth could stall later in the year.

The company expected its Chinese factories to restart on February 10, Mr. Farr told analysts and investors. The Chinese plants did come quickly back online. But Mr. Farr didn’t anticipate what came next.

“I’m Too Busy to Die”

Mr. Farr is old school. He runs an industrial conglomerate.

He likes golf and the company jet. He likes a glass of wine, or a vodka on the rocks, and goes on walks with his wife, Lelia, almost every night through their upscale neighborhood of Ladue just outside the city of St. Louis. He is up at 5:30 a.m. and tries to stop working around 8:00 p.m., but is still quick to answer emails later than that. He doesn’t watch television outside the office and spends most nights reading, lounging with Rocket and Doon, his two King Charles spaniels, and going to bed early.

He grew up in Corning, New York, where his father was a math teacher before becoming a plant manager at glass-maker Corning Inc. The job moved the family to England, where his mother died from a cerebral hemorrhage when Mr. Farr was eighteen.

Fresh out of business school, he joined Emerson in 1981 and rose through the ranks working for a tough CEO who ran the place for twenty-seven years with a focus on grinding down costs. Mr. Farr, too, is hard on his managers. His shouting is balanced by an affinity for hugs, handshakes, and kisses. He dictates long memos to his secretary and enjoys “good debates, bad debates, and yelling debates.”

He is politically conservative and an admirer of Jack Welch, the hard-nosed former boss of General Electric Co. At an investor conference in 2009, he said he wouldn’t hire more US workers because the Obama administration was out to “fundamentally destroy” manufacturing with its environmental and labor rules. He declares a lack of interest in politics, yet he talks with the White House, governors, and mayors and makes sure people know it.

Emerson’s salesman in chief rarely misses the chance to pitch the company’s products, even interrupting a conversation to tout a Ridgid “closet auger,” a device for unclogging toilets. He roots, in jest, for heat waves, storms, and flooding so Emerson can sell more air-conditioning compressors and wet/dry vacuums.

Mr. Farr keeps five baseball bats in his office, including one signed by St. Louis Cardinals greats Stan Musial and Albert Pujols. He likes to swing the bats while he thinks. During earnings calls, he is known to poke people with a bat if he thinks they aren’t doing a good job of talking to investors.

He has delivered steady gains for investors. Since he took over in October 2000, Emerson shares have logged a 311 percent total return, including dividends, compared with the 275 percent return from the S&P 500 Index, and a 239 percent return for the S&P Capital Goods Industry Group Index.

He was just forty-five when he was named CEO. Months into the job, he faced the bursting of the dot-com bubble in 2001 and the September 11 terrorist attacks. The company’s forty-three-year streak of earnings growth came to an end.

In an era of shrinking CEO tenures, Mr. Farr’s has also spanned the 2008 financial crisis and the 2014 racial unrest in Emerson’s hometown of Ferguson stemming from the fatal police shooting of Michael Brown, an unarmed Black teenager. Mr. Farr plans to retire next year, which means the pandemic will likely be his final challenge.

Though he didn’t serve in the military, Mr. Farr approaches crises as if he were commanding his troops from the front line. “I’m not going to die,” he said in the first weeks of the pandemic. “I’m too busy to die.”

Downward Slide

As February turned to March, the virus ebbed in China but emerged in a new hot spot: Northern Italy, where Emerson has five factories and nearly 2,000 workers. The government locked down areas around Lombardy and Milan, then widened the shutdown to other regions and eventually the entire country.

“Is it going to grow in just pockets or is it going to grow across the whole country?” Mr. Farr wondered.

A major Emerson conference for European customers scheduled for mid-March in Milan was canceled. The company pulled out of an oil-and-gas conference in Houston. In the relatively untouched US, Emerson started shutting down offices and giving employees instructions for working from home.

In early March, St. Louis reported its first case of coronavirus. Shortly after, pharmaceutical giant Bayer temporarily shut down a ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction by Rachel Feintzeig: Wall Street Journal

- The Stalwart: David Farr Emerson Electric

- The Stumblers: Jeffrey Katzenberg & Meg Whitman Quibi

- The New Chief: Sonia Syngal Gap

- The Persuader: Linda Rendle Clorox

- The Streamliner: Mary Barra General Motors

- The Work Futurist: Reed Hastings Netflix

- The Hard Charger: StéPhane Bancel Moderna

- The Mover: Jeff Shell Nbcuniversal

- The Adjusters: The Wegman Family Wegmans Food Markets

- The Small-Business Survivor: Frank Timberlake Rich Square Market

- The Rebel: Elon Musk Tesla