This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

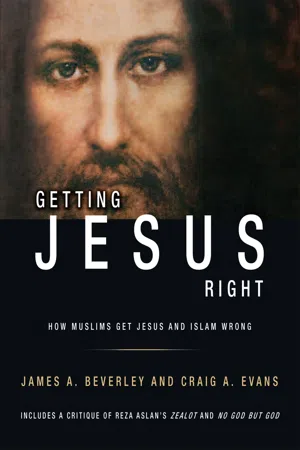

Getting Jesus Right: How Muslims Get Jesus and Islam Wrong

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

IS IT POSSIBLE THAT MUSLIMS ARE WRONG ABOUT JESUS AND VARIOUS TENETS OF ISLAM?Is the famous Muslim writer Reza Aslan mistaken in his portrayal of Jesus ofNazareth and apologetic for Islam? Professor James Beverley and Professor CraigEvans take an in-depth look at subjects at the core of the Muslim-Christian divide: the reliability of the New Testament Gospels and the Qur'an, and what we can really know about Jesus and the prophet Muhammad. Importantly, they also examine the implications of traditional Islamic faith on the status of women, jihad and terrorism.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Getting Jesus Right: How Muslims Get Jesus and Islam Wrong by James Beverley, Craig A Evans in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Systematic Theology & Ethics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

Systematic Theology & EthicsChapter 1—Are the New Testament Gospels Reliable?

Jesus and His Followers

All competent study of the historical Jesus begins with the four New Testament Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke and John). This is because they are the oldest sources and exhibit the features that historians expect of sources that are likely to provide reliable information. Of course, from time to time someone expresses skepticism about the New Testament Gospels. Sometimes Muslims express skepticism, especially when the Gospels and the Qur’an disagree. Therefore we begin our book by addressing the question of the reliability of the Gospels. Do these Gospels tell us the truth about Jesus, about what he taught, what he did, and what really happened to him?

One of the reasons it is good to begin with the Gospels is because they are biographies, based in part on eyewitness testimony. They were written 30 to 40 years after the time of Jesus, while some of his original followers were still living. The sources the Gospel writers drew upon circulated during this period, when the apostles of Jesus were active, teaching and giving leadership to the new movement. The Gospels are not biographies in the modern sense, but they are biographies as written in antiquity.1 We have good reasons for believing that these Gospel biographies in fact provide us with a great deal of useful, reliable material.

We do not begin with the Qur’an, not only because it was written almost 600 years later than the New Testament Gospels, but because it really is not a historical narrative or a biography. There may well be historical and biographical data within it, the kind of data that historians can utilize, but the Qur’an as a whole is obviously not a historical work. Later in our book we shall look at what the Qur’an and other early Islamic sources have to say about Jesus.

In this chapter, we will treat two important questions that relate to the Gospels as potentially accurate and useful biographical histories concerning the life, teaching and activities of Jesus. The first question asks how close the New Testament Gospels are to the time of Jesus. The second question asks if the information in the Gospels is based on the testimony of eyewitnesses.

How Close Are the New Testament Gospels to the Time of Jesus?

When it comes to comparing the Qur’an and the New Testament Gospels as potential historical sources, chronology and temporal proximity are very important. By temporal proximity we mean how close the written record is to the persons and events that the written record describes. Most historians agree that an account written within the lifetime of the participants and eyewitnesses is to be preferred to an account written centuries later. This is how historians think. They know, of course, that proximity is not the only criterion for evaluating the potential value a document has for historical research, but it is a very important criterion.

So when was the Qur’an written and when were the New Testament Gospels written? Muslims believe that Muhammad received the revelations that are in the Qur’an over a period of about 23 years, from AD 610 to 632, the year that he died. After Muhammad’s death, written materials were gathered, and memorized material was committed to writing.2 Within 20 to 70 years or so from the death of Muhammad, something pretty close to today’s Qur’an (“recitation”) had emerged. Most of the variant versions were gathered up and destroyed.3 Given the close proximity of the Qur’an to the lifetime of Muhammad, it is reasonable to assume that this book contains some of what Muhammad taught, or at least something pretty close, though there are difficult historical issues involved.

Jesus of Nazareth was born shortly before the death of Herod the Great, the Idumean prince whom Rome appointed as king over the Jewish people in 39 or 40 BC. After defeating the last native Jewish ruler, in 36 or 37, Herod became king in fact. He died in either 4 BC or 1 BC, which means Jesus was born in either 4/5 BC or 2 BC.4 Jesus began his public preaching and activities when he was about 30 (Luke 3:23). On the assumption that the death of Jesus took place in AD 30, it is likely that his ministry began in AD 28/29 and ran for about two years.5

Jesus was confessed by his followers as Israel’s Messiah and as God’s Son (e.g., Mark 8:29; Matt 16:16; Luke 9:20; John 1:49; 6:68–69). They and others regularly called Jesus rabbi and teacher. His closest followers were called disciples, which in Hebrew and in Greek means “learners.” This is important to remember: Jesus was known as a teacher (which is also what “rabbi” more or less meant in the first century; see John 1:38) and his closest followers were learners. And what did they learn? They learned Jesus’ teaching.

Judging by the length of the Gospels, the body of Jesus’ teaching was not extensive, especially when we remember that there is a great deal of overlap among the first three Gospels: Matthew, Mark and Luke. It was not difficult for a devoted follower to commit to memory most or all of Jesus’ teaching.6 It is also believed that much of this teaching was committed to writing and would later be drawn upon by the authors of Matthew and Luke.7

Most scholars think Mark was the first Gospel to be written and circulated. According to Papias (c. AD 125)8 the Gospel of Mark was composed by John Mark (Acts 12:12), who in the 50s and 60s AD assisted Peter, the lead disciple and apostle. Whereas the Gospel of Mark itself may have been penned in the mid- to late-60s, near the end of Nero’s rule (AD 54–68), the reminiscences of Peter may well have circulated for many years earlier. Of course, Peter himself would have preached and taught everywhere he went until he was imprisoned and executed c. AD 65. We have reason to believe that a collection of Jesus’ teachings also circulated perhaps as early as the 30s or 40s. Not too many years after the publication of Mark, the Gospels of Matthew and Luke were published and began to circulate. Later still, perhaps in the 90s (though some scholars argue for an earlier date), the Gospel of John was published.

Oldest Synoptic Gospels Papyri

That the teaching of Jesus circulated and was known well before the Gospels were written is demonstrated by the appearance of his teaching and aspects of his life and death in earlier writings, such as the letters of Paul, the earliest of which were penned in the late 40s. Paul often alludes to Jesus’ teaching, though sometimes he explicitly cites a “word” from the “Lord.” We see an example of the latter when Paul charges the people in the church at Corinth not to seek divorce: “To the married I give charge, not I but the Lord, that the wife should not separate from her husband…and that the husband should not divorce his wife” (1 Cor 7:10–11). It is the Lord, Paul says, who has given command that divorce should be avoided. Paul has appealed to Jesus’ teaching, which he gave in response to a question put to him concerning the divorce regulations in the Law of Moses (Matt 19:3–9; Mark 10:2–9). After quoting parts of Genesis 1:27 (“male and female he created them”) and 2:24 (“they become one flesh”), Jesus asserts, “What therefore God has joined together, let not man put asunder” (Mark 10:6–9).

Another obvious Jesus tradition in one of Paul’s letters is the citation of the Words of Institution, that is, the words Jesus spoke at the Last Supper (Matt 26:26–29 = Mark 14:22–25 = Luke 22:17–20). Paul finds it necessary to instruct the church at Corinth, reminding them of what Jesus did and said on that solemn occasion:

For I received from the Lord what I also delivered to you, that the Lord Jesus on the night when he was betrayed took bread, and when he had given thanks, he broke it, and said, “This is my body which is for you. Do this in remembrance of me.” In the same way also the cup, after supper, saying, “This cup is the new covenant in my blood. Do this, as often as you drink it, in remembrance of me.” (1 Cor 11:23–25)

Paul’s wording matches the form of the story in Luke very closely, which probably should not occasion surprise, for Luke the physician traveled with Paul on some of his missionary journeys.9

Of even greater significance is the appearance in Paul’s letters of allusions to Jesus’ teaching. When the apostle commands, “Bless those who persecute you; bless and do not curse them” (Rom 12:14), he has echoed the words of Jesus: “Love your enemies…bless those who curse you” (Luke 6:27–28); “Love your enemies and pray for those who persecute you” (Matt 5:44). When Paul speaks of mountain-moving faith, saying “if I have all faith, so as to remove mountains” (1 Cor 13:2), he has alluded to Jesus’ famous teaching: “if you have faith…you will say to this mountain, ‘Move from here to there,’ and it will move” (Matt 17:20). When Paul warns the Christians of Thessalonica that “the day of the Lord will come like a thief in the night” (1 Thess 5:2), he has alluded to the warning Jesus gave his disciples: “if the householder had known in what part of the night the thief was coming, he would have watched” (Matt 24:43). Paul’s admonition that the Thessalonian Christians “be at peace among” themselves (1 Thess 5:13) echoes Jesus’ word to his disciples that they “be at peace with one another” (Mark 9:50).10

Paul is not the only New Testament writer to show familiarity with the teaching and stories of Jesus; the letter of James is filled with allusions to the teaching of Jesus.11 There are important allusions in Hebrews and 1 and 2 Peter also. All of this shows that the teaching of Jesus was in circulation long before the Gospels were written, and even when the three early Gospels (Matthew, Mark, and Luke) were written, many of Jesus’ original followers were still living and active in the Church.

What all of this means is that the four New Testament Gospels were written early enough to contain accurate data relating to the teaching and activities of Jesus. Three of the four Gospels were written within the lifespan of many of Jesus’ original disciples. The Gospels were not written hundreds of years after the ministry of Jesus and the birth of the Church; they were written toward the end of the first generation. And the New Testament Gospels are not the oldest documents in the New Testament. Older writings, such as the letters of Paul (and probably James as well), contain quotations, allusions and echoes of the same material.

But what about the Jesus stories and teachings in the Qur’an that are distinctive to the Qur’an? Should we accept these materials as authentic and therefore historically reliable? And if the Qur’an’s version of the Jesus tradition contradicts the tradition of the New Testament Gospels, should the Qur’an’s version be preferred?

The first and most obvious problem with the Qur’an as a source for new stories and teachings that supposedly go back to Jesus is that the Qur’an was written 600 years after the ministry of Jesus. We don’t doubt that the Qur’an might give us some authentic thoughts and teachings of Muhammad. Several friends and supporters who had heard his teaching were still living after he died and were able to assemble his teaching and write out the Qur’an. The Qur’an was written in its final form only about one generation after the death of Muhammad (though the process of editing may have continued for another generation or two), just as the New Testament writings were written only about one generation after the death and resurrection of Jesus.12

But does this mean that the Qur’an is a reliable source for the historical Jesus, especially if in places it contradicts what is said in the first-century Christian Gospels? No, it does not. The problem is that the Qur’an was written more than half a millennium after the time of Jesus, some 550 years after the writing of the New Testament Gospels. No properly trained historian will opt for a source that that was written more than five hundred years after several older written sources.

We face the same problem with distinctive Jesus traditions in the rabbinic literature. Jesus appears in the Tosefta, which cannot be dated earlier than AD 300, or about 225 years after the New Testament Gospels were written. More traditions about Jesus appear in the two recensions of the Talmud. The Palestinian recension dates to about 450 AD, while the Babylonian dates to about AD 550. Historians and serious scholars find this material colorful, even entertaining, but they view it with suspicion as regards trustworthiness about Jesus. And why shouldn’t they? These compendia of Jewish law and lore were compiled hundreds of years after the time of Jesus and the New Testament Gospels. They are almost as far removed in time as the Qur’an. Historians make little use of rabbinic literature as historical sources in writing about the historical Jesus.

As we will see in a later chapter, almost all of the Qur’an’s distinctive Jesus tradition seems to have been derived from later times and places, such as Syria in the second and third centuries. The Jesus of the Qur’an seems to be very much colored by the type of asceticism that was taught in second- and third-century Syrian Christian circles, such as the Encratites. Some of the sources on which Muhammad relied are quite dubious, such as the Infancy Gospel stories (where, for example, Jesus gives life to birds made of mud) or the strange idea of Basilides (who said it was not Jesus who was crucified but some poor fellow who looked like Jesus). Some of Jesus’ alleged pronouncements in the Qur’an (e.g., where Jesus denies his divinity) reflect the debates and polemics that were part of Muhammad’s context in Arabia in the late sixth and early seventh centuries, not the context of Jesus and his contemporaries in first-century Israel. Indeed, the Jesus of the Qur’an is largely an imagination of a mid-seventh century religious community.13

For all of these reasons, very, very few historians make use of the Qur’an as a sou...

Table of contents

- Title Page

- Praise for Getting Jesus Right

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Chapter 1—Are the New Testament Gospels Reliable?

- Chapter 2—Are the Manuscripts of the New Testament Gospels Reliable?

- Chapter 3—How Did Jesus Understand Himself and His Mission?

- Chapter 4—Did James and Paul Preach a Different Gospel?

- Chapter 5—Was Jesus a Zealot?

- Chapter 6—How Do Muslims View Muhammad?

- Chapter 7—How Reliable Is the Historical Record about Muhammad?

- Chapter 8—Is Muhammad the Greatest Moral and Spiritual Model?

- Chapter 9—How Do Muslims View the Qur’an?

- Chapter 10—Is the Qur’an God’s Infallible Word?

- Chapter 11—Does the Qur’an Get Jesus Right?

- Chapter 12—Does the Qur’an Get the Death of Jesus Right?

- Chapter 13—Does Islamic Tradition Get Jesus Right?

- Chapter 14—Does Islam Liberate Women?

- Chapter 15—Is Islam a Religion of Peace?

- Chapter 16—Easter Truths, Muslim Realities and Common Hope

- Appendix 1—Reza Aslan’s Zealot: Wrong at Many Points

- Appendix 2—Was Jesus Married to Mary Magdalene?

- Appendix 3—Modern Studies on the Qur’an

- Appendix 4—New Testament Background and the Growth of Christianity

- Appendix 5—Timeline of Islam

- Appendix 6—The Islamic State and The Atlantic

- Appendix 7—The Infamous Fox News Interview

- Resources

- Endnotes

- Index of Scripture and Ancient Writings

- Also by James A. Beverley