This is a test

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

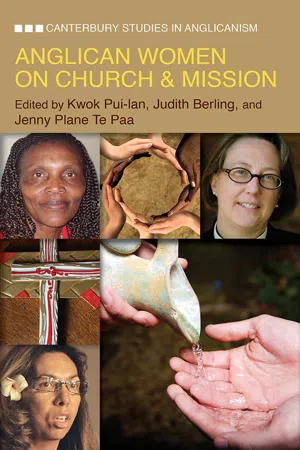

Anglican Women on Church and Mission

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In the past several decades, the issues of women's ordination and of homosexuality have unleashed intense debates on the nature and mission of the Church, authority and the future of the Anglican Communion. Amid such momentous debates, theological voices of women in the Anglican Communion have not been clearly heard, until now. This book invites the reader to reconsider the theological basis of the Church and its call to mission in the 21st century, paying special attention to the colonial legacy of the Anglican Church and the shift of Christian demographics to the Global South. In addition to essays by the volume editors, this 12-essay collection includes contributions by Jane Shaw, Ellen Wondra and Beverley Haddad, among others.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Anglican Women on Church and Mission by Judith Berling in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Denominations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

Christian DenominationsPART 1

ANGLICAN HISTORICAL

AND THEOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVES

ON THE CHURCH

AND THEOLOGICAL PERSPECTIVES

ON THE CHURCH

1

FROM A COLONIAL CHURCH TO

A GLOBAL COMMUNION

A GLOBAL COMMUNION

Kwok Pui-lan

The Anglican Communion was formed as a result of the expansion of colonialism and mission work in the colonies. Beginning in the seventeenth century, Anglican churches were established in the settler colonies in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, South Africa, and the eastern part of the United States. By the mid-1860s, a large number of overseas Anglican dioceses were effectively independent of the Church of England, having their own patterns of government and discipline and procedures for electing bishops. Controversy over the position of churches in the colonies led the Canadian bishops to request Archbishop of Canterbury Charles Longley to convene a meeting of all the bishops of the Anglican Church, both at home and abroad. Lambeth Conference 1867 marked the beginning of Anglican churches coming together to discuss their common concerns and affairs. Of the seventy-six bishops gathered at Lambeth Palace, many shared very similar backgrounds, as the colonial bishops and the English bishops had mostly gone through an education at Oxford or Cambridge.1

The idea of an Anglican Communion slowly took root and became more popularized in the first half of the twentieth century. After the Second World War, the diversity within the Communion was heightened, when many African and Asian countries regained political independence and struggled to assert cultural autonomy. Lambeth 1948 endorsed the United Nations’ proposed Covenant on Human Rights and declared that these rights belong to all men (sic) irrespective of race and color.2 The Conference also discussed the relation between the Church and the modern state.

Since the end of the Cold War, the term “globalization” has been widely used in the 1990s to describe changes brought by the neoliberal market, the information highway, and the use of new technology. The global character of the Anglican Communion has been recognized and strengthened by more connections between member churches in the North and in the South. While membership in mainline denominations in the North Atlantic has continued to decline, churches in the South experience growth and vitality. The global breadth was shown at Lambeth 1998, attended by nearly 750 bishops, including 224 from Africa, 177 from the United States and Canada, 139 from the United Kingdom and Europe, 95 from Asia, 56 from Australia, 41 from Central and South America, and 4 from the Middle East.3 The voices of churches in the global South could no longer be ignored. They have significantly changed the discussion in the Communion.

Within the academy, the study of world Christianity has gained momentum, with prominent scholars such as Andrew Walls and Lamin Sanneh pushing for more attention to be paid to African churches. Several important works on the Anglican Communion have been published, which study the history of the Communion, the trajectory from colonial to national churches, and the struggles from a church of the British Isles to become a postcolonial and multicultural church.4 Several of them feature authors who are lay and ordained scholars across the Communion.5 In recent years, the controversies over women priests and bishops and homosexuality have generated poignant conversations on the identity, authority, and future of Anglicanism. This chapter begins with a discussion on the crisis of Anglican identity. Using the examples of polygamy and homosexuality, it examines how race, gender, and sexuality have shaped the cultural politics of the Anglican Church. The final section offers some comments on the future of the Anglican Communion.

The Crisis of Anglican Identity

An important challenge facing the Anglican Communion is how to be accountable to each other, when controversies and conflicts arise. Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams acknowledged that the issues that threaten to divide the Communion are not limited to human sexuality, but could include “developments about how we understand our ordained ministry; how we understand our mission; the limits of diversity in our worship; even perhaps in the public language we use about our doctrine.”6 That the Anglican Church has not come to some common understanding on so many fundamental aspects of the Church and its mission points to the deep crisis of Anglican identity.

The crisis of Anglican identity can be attributed to many causes. The Anglican Church is not a confessional church and does not have the equivalent of the Augsburg Confession and the body of official doctrines similar to those of Lutheranism. It was formed more out of political expediency by Henry VIII, rather than out of rigorous theological arguments similar to those advanced by Luther and Calvin. The Thirty-nine Articles, which served to define the doctrine of the Church of England during Reformation, are not officially normative in all Anglican churches. The Chicago-Lambeth Quadrilateral adopted by Lambeth 1888 laid out the broad consensus of the Church: the Scripture as containing all things necessary to salvation, the Apostles’ Creed as the sufficient statement of Christian faith, the two sacraments of baptism and Eucharist as ordained by Christ himself, and the emphasis on the historic episcopacy as the basis of Christian unity.7 While the Quadrilateral can serve as a foundation to discuss Christian unity and ecumenism with other churches and denominations, it does not spell out the uniqueness of Anglicanism.

Some of the most prominent Anglican theologians even debated whether Anglicanism has special doctrines of its own. Several modern interpreters, such as Michael Ramsey, Stephen Neill, and Henry McAdoo, insist that the Anglican Church is a part of the historical Christian tradition that embraces the creeds and doctrines of the early church and does not have unique doctrines of its own. Such a claim emphasizes the intention of Anglicanism to be Catholic, to remain in the mainstream, and to be part of the whole.8 Others, such as Stephen Sykes, argue that “the no special doctrines” claim is a fallacy, for every Church must have a doctrine of the Church to legitimize its existence and maintain its integrity. Sykes writes, “While it may have been true that there is no specifically Anglican Christology or doctrine of the Trinity, or even (though it could be disputed) doctrine of justification, it cannot be the case that there is no Anglican ecclesiology.”9

But even if one wishes to study the doctrine of the Church in the Anglican Church, as Paul Avis notes, one is immediately faced with the issues of the diversity of Anglicanism and the problem of selectivity.10 The Anglican Church does not have a teaching office similar to that of the Roman Catholic Church and it is not easy to appeal to certain texts or writers as “typical” or “representative.” The historical scope and geographical extent of Anglicanism further undermine any easy generalizations. There is no single period of Anglican history that can be seen as definitive and can serve as the paradigm for developing Anglican ecclesiology. In addition, Anglicanism is a global phenomenon, existing in many social and cultural contexts. While the historical texts developed in sixteenth- and seventeenth-century England and Ireland constitute a common legacy, member churches in the Communion have developed their Anglican theology to address their own issues. Richard Hooker’s classic text, Of the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity,11 written in the sixteenth century in the context of the established Church of England, cannot be easily applied to other churches with totally different church-state relations.

If it is not easy to define Anglican identity by its doctrines and theological locus, many turn to its common liturgy, because Anglicans are fond of saying lex orandi, lex credendi (the law of prayer is the law of belief). The Book of Common Prayer serves for some as a pointer to conformity and koinonia (communion) of member churches. Yet the provinces have freedom in revising their Book of Common Prayer and many modern revisions have come out. It was often difficult to balance between historical continuity and cultural relevance. By Lambeth 1958, it was acknowledged that the Prayer Book was no longer the basis for unity.12 New liturgies emerged to meet the needs of different cultures. For example, the widely acclaimed New Zealand Prayer Book is bicultural and bilingual (Maori and English), and includes the cosmological worldviews, idioms, and languages of the Maoris.13 Another example can be found in one of the Eucharistic prayers of the Episcopal Church’s Book of Common Prayer, which includes modern language in its reference to God’s creation. It addresses God as ruler of the universe, who creates “the vast expanse of interstellar space, galaxies, suns, the planets in their courses, and this fragile earth, our island home.”14

Even the elements used for Eucharist could be controversial, as the question of substitution of bread and wine has arisen. Some churches consider bread and wine to be “foreign” imports; others claim that there are elements in their local culture to convey the notion of the celebratory meal better than bread and wine. In Islamic countries, the government outlaws all alcoholic drinks and it is hard to obtain wine. Some churches need to respond to concerns of recovering alcoholics and the needs of those who have gluten allergies. The discussion of food and drink at Eucharist touches on theological issues, but also on cultural authenticity and adaptability, given the diversity of the Communion.15

The discussion of theology and liturgy has already touched on the complex issues of cultural difference in the Communion. Some scholars attribute the crisis of Anglican identity to the difficulties of the transition of an English church to a global multiracial, multicultural, and multilingual Communion. Writing in 1993, before the heated debates erupted in recent decades, William L. Sachs already noted: “The deepening of local influences upon the Church brought forth a profusion of religious forms, all claiming historic precedent and religious validity, which shattered the unity of Anglican identity. The modern question became one of mediating between diverse forms of Anglican experience.”16 Ian T. Douglas, a member of the Design Group for Lambeth 2008, has gone one step further in his critique of the cultural domination and the continued colonial patterns of power in the Anglican Communion. For him, the crisis in the Anglican Communion is not so much about structure and instruments of unity, but about relationships and mission. In order for the Church to advance God’s mission of reconciliation and restoration, the Church must respect and embrace what he has called “different incarnational realities.”17 He writes, “Communion is thus primarily based upon relationships of mutual responsibility and interdependence in the body of Christ across the differences of culture, location, ethnicity, and even theological perspective to serve God’s mission in the world.”18

The issue of cultural difference has arisen in the Anglican Communion since its inception. Lambeth 1867 was convened in part to settle the “Colenso Affair.” John Colenso, Bishop of Natal in South Africa, was criticized for undermining the authority and inerrancy of Scripture by using the historical method to study the Bible. Sympathetic to Zulu culture, he challenged the missionaries’ condescending attitudes toward the “heathens.” He insisted that God is revealed to all humanity and that revelation is not confined to one nation and to one set of books. Colenso approached the Bible through wider and comparative lenses and insisted that Christ redeems all people everywhere whether they have heard his name or not.19 Colenso was tried for heresy and appealed his case all the way to England. The Colenso affair brought into focus questions that would engage the Anglican Communion for years to come, such as Gospel and culture, diversity in biblical interpretation, the nature of Church, relations in the Communion, and the authority of the Lambeth Conference. In the following section, I use the examples of polygamy and homosexuality to examine the intersection of race, gender, and sexuality in the cultural politics of the Anglican Communion. It underlines the twists and turns of the transition from a colonial church to a global Communion.

The Cultural Politics of Polygamy and Homosexuality

During the colonial days, differences in marriage, sexual norms, and family structures served to reinforce cultural superiority of the colonizers over the colonized. English missionaries, shaped by their Victorian marriage norms and domesticity, found polygamous marriage troubling and against their Christian upbringing. Although polygamy was practiced in most societies encountered by missionaries in the nineteenth century, it was in Africa that polygamy became most problematic for the churches, including the Church of England.20 Traditional African marriages were arranged between families and often involved the exchange of bride wealth in the form of cattle. Multiple wives served as a sign of wealth, children, power, and status.

Missionaries and the mission societies frequently raised the question of how to deal with polygamy. While the majority of missionaries upheld the monogamous ideal, a small minority, including Bishop Colenso, argued that polygamy should not be a barrier for baptism and exclude a person from becoming a full member of the Church.21 Lambeth 1888 allowed for the baptism of polygamous wives, but resolved that “persons living in polygamy be not admitted to baptism, but that they be accepted as candidates and kept under Christian instruction until such time as they shall be in a position to accept the law of Christ.”22 The resolution did not resolve the issue, but rather created further problems, because it implied that a polygamous husband had to divorce all but one of his wives in order to receive baptism. But the churches at the time opposed divorce in general. In the African familial system, women deserted by their husbands had little means of supporting themselves and their children.

Throughout the twentieth century, polygamy continued to be an issue for the Anglican Church. The matter was brought up repeatedly at various Lambeth Conferences. The Archbishop of Canterbury commissioned a survey of the treatment of polygamous converts in the Anglican Communion leading up to Lambeth 1920. The Conference maintained the ban on the baptism of men living in polygamy. Timothy Willem Jones notes that the tone of church proclamations regarding polygamy softened after the Second World War, when the African countries became decolonized.23 Lambeth 1958 maintained that monogamy is the divine will, but recognized that “the introduction of monogamy into societies that practice polygamy involves a social and economic revolution and raises problems which the Christian Church has as yet not solved.”24 The 1968 Conference reaffirmed monogamous lifelong marriage as God’s will and acknowledged that polygamy posed “one of the sharpest conflicts between the faith and particular cultures.”25

The issue of polygamy was also brought up in the meetings of Mothers’ Unions in Africa. The Mothers’ Union, an Anglican organization begun in England, spread to Africa and had a strong presence in the continent. The Union was set up to strengthen Christian marriage and to promote the well-being of families. Anglican scholar Esther Mombo notes that in Kenya, the Mothers’ Union discussed marriage and polygamy in their early meetings beginning in the late 1950s.26 The missionaries who founded the Mothers’ Union spoke against polygam...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- About the Contributors

- Introduction

- Part 1 - Anglican Historical and Theological Perspectives on the Church

- Part 2 - Anglican Women and God’s Mission

- Epilogue - Judith A. Berling

- Notes

- Index