eBook - ePub

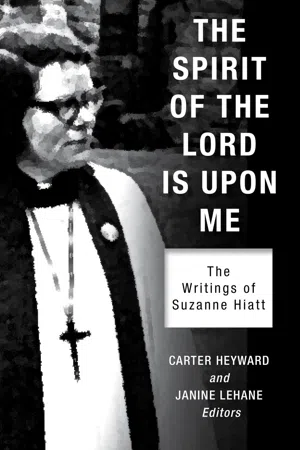

The Spirit of the Lord Is Upon Me

The Writings of Suzanne Hiatt

Carter Heyward,Janine LeHane

This is a test

- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Spirit of the Lord Is Upon Me

The Writings of Suzanne Hiatt

Carter Heyward,Janine LeHane

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The writings of Sue Hiatt, considered "bishop to the women" and leader of the movement that led to the ordination of women in the Episcopal Church.

Quiet, introspective, passionate, strong-minded, Sue Hiatt's road to Christian feminism began as a teenager. These writings, alongside material by Carter Heyward and others critical to the movement, are a vital source of study, reflection, and inspiration.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The Spirit of the Lord Is Upon Me an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The Spirit of the Lord Is Upon Me by Carter Heyward,Janine LeHane in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Teología y religión & Religión. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Teología y religiónSubtopic

Religión

THE RADICAL

LADY WHO CHANGED

THE CHURCH

LADY WHO CHANGED

THE CHURCH

Introduction to Part One

The Radical Lady Who Changed the Church

If you read only one essay in this book, this should be it. Initially a speech to the Ecumenical Conference on Women’s Ministries at Graymoor Conference Center, Garrison, New York, in March 1983, this piece carries the reader into the core of Sue Hiatt’s passion for justice for women and her strategic intelligence about how to make it happen—in this case the ordination of women priests—in one relatively small organization, the Episcopal Church in the United States. This essay is a case study in community organizing. It is also a manifesto in feminist pastoral theology, which might be defined as reflections on God in ways that strengthen women, thereby contributing to the healing of their wounds and to their refusal to make peace with their own oppression.

Hiatt contends here that women must “take” authority, rather than wait to have it bestowed upon us, if significant change is to be brought about in realms of gender equality. She speaks both politically, about how social change generally happens, and personally, about her own vocation: “I realized … my vocation was not to continue to ask for permission to be a priest, but to be a priest.” This sensibility is present early in Hiatt’s own life. The theme of her high school honors paper (see part two, “The Domestic Animal”) is that women need to take responsibility for our own lives, and assume authority for and insist upon the conditions in which we will live. Sue Hiatt has little use for women whining about, or resigning ourselves passively to, sexist behavior on the part of individuals or society. If you don’t like it, do something about it, is her mantra.

She is cool and strategic in sorting out the relationships in which she and the other feminist women activists found ourselves in the 1970s. Referring to the bishops who wanted to ordain women but felt, for various reasons, that they couldn’t take this step as quickly as we were demanding, Sue Hiatt writes, “They were our friends and allies but, since they could go no further, we had to go on without them.” She did not hesitate to lead women deacons out of a meeting in New York City in 1973 with these very bishops, our “friends and allies,” by commanding in her soft, understated way, “Sisters, let’s vote with our feet!” So out we walked, leaving behind the men who, until then, had perceived themselves as our best hope. In that moment, the women deacons and our bishops realized that we women were our own best hope.

Hiatt concludes this essay, which should be required reading for women and men who intend to bring about social change in the church, academy, or elsewhere, with four “principles” for organizing:

1. Women, or others who seek social change that will affect them in a primary way, must take a primary role in bringing that change about. Women are their own best advocates and they have no reason to apologize for this. In fact, it should make us proud to be women—and to be advocates for ourselves and our sisters.

2. We must learn how the institutions that we wish to change actually work and how best to influence them. This is the basis of good strategy, which was one of Sue’s special gifts as a social worker trained in community organizing.

3. We women must be united and avoid horizontal violence—that is, we must avoid sniping at other women with whom we may have different strategies but with whom we share long-term goals. More than anything, we must avoid blaming women for sexist oppression and violence against women. At the same time we must hold women responsible for struggling together against such oppression and violence.

4. Specifically in relation to the church, we women must remember that the church needs us. Later in life, Hiatt would add, “… more than we need the church.” Implicit in her life and work, throughout this essay and this book, is Sue Hiatt’s belief that women could live strong, creative, spiritually rich lives without the church—and would do better without the church than to continue to submit ourselves to the church’s oppression and its trivialization of women.

C.H.

How We Brought the Good News

from Graymoor to Minneapolis

from Graymoor to Minneapolis

An Episcopal Paradigm

Journal of Ecumenical Studies 20, no. 4 (Fall 1983): 576–84

When I was asked to speak at this conference, I accepted the invitation immediately and enthusiastically. The time was right, I felt, to tell the story of women’s battle for ordination in the Episcopal Church. Women are good at telling stories, but we are less good at learning from those stories, and not good at all at recalling and cherishing our own history (even when we call it “herstory”). So I have a story to tell—a history to recapture. I hope we can all learn from the recalling of these events.

You probably know that women may serve in all orders of ministry in the Episcopal Church and that the Episcopal Church is the United States manifestation of the worldwide Anglican Communion. You may remember that in the summer of 1974, in Philadelphia, three retired and resigned Episcopal bishops ordained eleven women deacons to the priesthood without the consent of the bishops under whom the women served or the consent of the church at large. You may also remember that in September 1976, the Episcopal Church in general convention in Minneapolis voted approval for the ordination of women to the priesthood. Women began to be ordained regularly and legally in January 1977. It is these events and the actions of churchwomen leading up to them which I recall here.

In the prayerbook ordination service according to which I was ordained priest in July 1974, the bishop in laying hands on the head of the ordinand recites this formula: “Take thou authority to execute the office of a Priest in the Church of God, now committed to thee by the imposition of our hands.” I had often pondered that transfer of authority when I attended ordinations. The bishop does not confer priestly authority but simply tells the ordinand to assume it. The story of the ordination of women priests in the Episcopal Church is a case study of women “taking” authority, and that is what is instructive about it. Somehow over the past fifteen years women in my church (and in many of your churches and synagogues as well) were able to take the initiative and to change institutions not noted for their susceptibility to change. The details vary with the struggles, but women’s taking the initiative and stepping away from our time-honored position of supplicant is what has changed about women vis-à-vis the church.

Beginning at Graymoor

The story of women’s taking authority in the Episcopal Church began at Graymoor in April 1970. If I had to pick a moment it would be the sharing of an agapé (since of course none of us were priests or even deacons at that time) on Orthodox Easter. On that bright April morning about sixty Episcopal women gathered out on the lawn to close a two-day conference and to strengthen our resolve to insist on the opening of all aspects of the church’s ministry to women. The conference had grown out of the secular women’s movement, which was itself beginning to grow out of the anti-racist and peace movements of the late 1960s. In fact, the conference had been organized by women active in the Episcopal Peace Fellowship who simply sent out a call to all women on their mailing list to come together to discuss the church’s discrimination against women.

It was a difficult conference, as it had attracted a very diverse group of women. There were young militant feminists who felt peripherally connected to the church but very wounded by it. There were seminary-educated women of all ages, many of whom had never found fulfilling ministries within the church. There were laywomen just barely hanging on, and nuns and clergy wives who felt trapped and exploited by the institutional church. A few of the women had owned their own vocations to priesthood.

We fought and talked and cried together for two days and finally came up with “the Graymoor Resolution” in which we branded the institutional Episcopal Church “racist, militaristic and sexist. Its basic influence on our own lives is negative.” We resolved further “that women as well as men [must] be accepted and recognized as equals so that they may function in proportion to their numbers in all aspects of the Church’s life and ministry, including but not limited to …” and here we listed every office in the church we could think of, from vestries to altar guilds and from bishops to thurifers. We agreed on the final wording and signed the document in the course of that Easter agapé.

The Graymoor meeting did not lead directly to further organizational activity. The resolution was distributed and widely publicized, but no follow-up meetings were arranged, nor was an organization begun. But women began to take authority at Graymoor thirteen years ago simply by meeting together as women and sharing with other women what we had all been thinking privately for some time. We began to connect—to meet and know each other and to affirm ourselves as sisters.

The Episcopal Church meets in General Convention every three years, and such a convention was coming up in October 1970. The 1967 convention had appointed a commission on ordained and licensed ministries to look into the matter of women’s ministries, but no one at church headquarters had gotten around to convening it. In May and June of 1970, some of the Graymoor veterans discovered that the commission was made up of people who, if they met, would most likely propose that women be ordained to all orders of ministry. We persuaded them to meet rather than report “no progress” as headquarters had requested, and, after a September meeting, they came to the convention in Houston with such a resolution. In addition, four women came to that October convention to discuss our call to priesthood. With the help of some experienced church politicians and publicists (male clergy), the women and the commission recommendation caught the interest of the convention. In fact, the resolution to ordain women was debated and voted on—winning the approval of a majority of clerical and lay delegates, but losing by a narrow margin in the clergy order due to the technicalities of how the votes are counted.

The issue of women’s equality engaged many women at the convention, and on the morning after the defeat of the ordination resolution about fifty women crowded into a small hotel room to caucus on our response. The response was angry and forceful. Women had just been seated as lay delegates after a twenty-five-year debate and the church was congratulating itself on that, when suddenly the women were no longer grateful but turned hostile. The result of the women’s anger was the last-minute approval by the convention of the ordination of women to the diaconate on the same basis as men. Over the next few years women seminary graduates began to be ordained as deacons.

Doing Things Decently and in Order

In April 1971, I took a trip through the Midwest to test the waters on whether Episcopal women might be organized to press for the full ordination of women. I was a trained, experienced community organizer, having worked for several years for the Philadelphia Welfare Rights Organization. But, like most women, I knew nothing about church politics. As a professional I also knew that it was not a good idea for an organizer to work on an issue in which she has a deep personal stake (I was scheduled to be ordained deacon in June 1971). My talks with women in Detroit and St. Louis convinced me, however, that Episcopal women were ready to claim their place in the church and that someone with the skills to help them do it would be a valuable catalyst.

For the next two years we worked to build a network and an organization to influence the 1973 convention to be held in Louisville, Kentucky. We enlisted sympathetic bishops, priests, and laymen, but the major work was done through the Episcopal Women’s Caucus, organized at Alexandria, Virginia, on Halloween, 1971. Through regional branches the caucus researched and worked on the delegates to the upcoming convention. Organizing and educational events and meetings were held all over the country, and literature designed for varying levels of sophistication was produced. Again, with the help and advice of knowledgeable church politicians, we built a groundswell of enthusiasm for women’s ordination.

But the opposition was also hard at work organizing a groundswell against such a plan. By the time the convention was held there were about forty women in deacon’s orders (in addition to about seventy mostly elderly deaconesses who had been made deacons by the action of the 1970 convention). We were highly visible in clerical garb and on our best “winning of hearts and minds” behavior. This time the issue came as no surprise to the delegates, and they were cajoled and buttonholed by both sides. When the vote finally came, women’s ordination lost again. Again there was a majority of delegates voting yes, but this time the motion lost on the same technicality in both the clergy and lay orders.

By now the ordination of women was no longer a simple matter of equity that people had not thought about before, but a full-blown political issue threatening to “split the church.” In 1973, most delegates were faced with the decision of whether it would be more trouble for the church to ordain or not to ordain women, and they decided it would be more trouble to do it. In 1976, when faced with the same question, the delegates decided it would mean more trouble not to do it. How the atmosphere changed so dramatically is the story of women at work in the intervening three years.

Moving Toward Irregular Ordination

Even before the Louisville convention had adjourned, a group of women and bishops had met to talk about “irregular” ordination of women to the priesthood. The meeting was not a happy one, as several bishops and a few women had come to dissuade the others. Some of us, however, had felt a growing urgency in our vocations and had been increasingly aware that dramatic action was needed to break the logjam.

As early as 1965, I remember joking with a seminary classmate about his becoming a bishop and laying hands on me “suddenly.” As late as the spring of 1973, I had had a conversation with J. A. T. Robinson, an English bishop, in which we had agreed that the only way women’s ordination would come to the Church of England would be for a bishop or bishops simply to proceed to ordain a woman. After the defeat in Louisville, I had run into an older woman friend wise in the ways of the church who had remarked that she guessed the ordination of women would now become a perennial issue for general conventions, just as allowing women to vote as delegates had been from 1946 to 1970. Instantly I realized she was rig...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Prologue

- Part one: The Radical Lady Who Changed the Church

- Part Two: The Making of a Feminist Priest

- Part Three: “Bishop to the Women”

- Part Four: Setting the Captives Free

- “We Will Meet Again”

- Remembering Sue

- Reference List

Citation styles for The Spirit of the Lord Is Upon Me

APA 6 Citation

[author missing]. (2014). The Spirit of the Lord Is Upon Me ([edition unavailable]). Church Publishing Incorporated. Retrieved from https://www.perlego.com/book/3047504/the-spirit-of-the-lord-is-upon-me-the-writings-of-suzanne-hiatt-pdf (Original work published 2014)

Chicago Citation

[author missing]. (2014) 2014. The Spirit of the Lord Is Upon Me. [Edition unavailable]. Church Publishing Incorporated. https://www.perlego.com/book/3047504/the-spirit-of-the-lord-is-upon-me-the-writings-of-suzanne-hiatt-pdf.

Harvard Citation

[author missing] (2014) The Spirit of the Lord Is Upon Me. [edition unavailable]. Church Publishing Incorporated. Available at: https://www.perlego.com/book/3047504/the-spirit-of-the-lord-is-upon-me-the-writings-of-suzanne-hiatt-pdf (Accessed: 15 October 2022).

MLA 7 Citation

[author missing]. The Spirit of the Lord Is Upon Me. [edition unavailable]. Church Publishing Incorporated, 2014. Web. 15 Oct. 2022.