This is a test

- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

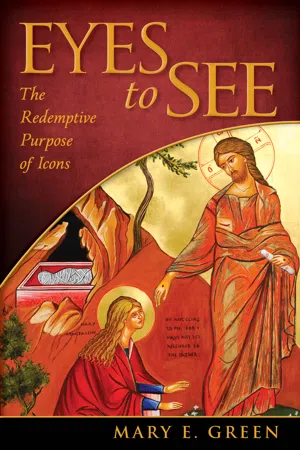

About This Book

Eyes to See: The Redemptive Purpose of Icons offers the discovery of life-giving spiritual insights found through learning to read the language of religious icons. Written especially for those whose traditions have not included icons, this book introduces eight icons written (painted) by the author. Historical notes, explanation of symbolism, related scriptures for interpretation, and a reflection for each icon deepens understanding and appreciation for the ancient holy images of the Church. The book is eight chapters in length, each describing one of the eight full-color icon plates in the insert.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Eyes to See by Mary E. Green in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Rituals & Practice. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

Theology & ReligionSubtopic

Christian Rituals & PracticePART I

Discernment ~ Receptivity

Theotokos, God Bearer

The place God calls you to is the place where your deep gladness and the world’s deep hunger meet.

—Frederick Buechner

I do think it would be worthwhile for you to reconsider Mary, and if she has no place thus far, to ponder inviting her to be a part of your prayer life. … If we return to the mystery of the cosmos in her womb, we may begin to view the world and our place in it differently. We may reverence all creation as sacred and do what we can to preserve and treat it that way.

—Br. Eldridge Pendleton, SSJE 9.8.11

Icon Authenticity: Beginning at the Beginning

The iconographer starts each day of painting with a prayer that begins: “O Divine Lord of all that exists, thou hast illuminated the apostle and evangelist Luke with thy Holy Spirit, thereby enabling him to represent thy Most Holy Mother, the one who held thee in her arms and said: The grace of him who has been born of me is spread throughout the world!”

Ancient tradition says Luke wrote three icons of Mary sometime after Pentecost, making him the first person to write holy icons.1 Historians claim Luke’s original prototypes of Mary were distributed from Jerusalem to Constantinople, Rome, and Antioch. St. Germanus, Patriarch of Constantinople (715–730 C.E.), wrote that “most excellent Theophilus” (Luke 1:3, Acts 1:1) for whom Luke/Acts were written had been the recipient of two of Luke’s originals.2 When Christianity was accepted as a state religion in the early fourth century, previously hidden religious objects were brought out and placed in public church buildings. Pope Gregory I (590–604 C.E.) is said to have carried one of Theophilus’ icons of Mary in procession when it was moved to the original basilica of St. Peter in Rome.3 Scores of Mary icons claimed to be Lucan originals exist today in Russia, on Mount Athos, Jerusalem, and Rome, but it is certain that none of Luke’s actual icons is extant. Instead, these ancient icons are believed to be the earliest reproductions of Luke’s three prototypes.4

Icons of Mary are called Theotokos, Greek for “God bearer” or “Mother of God,” the name commonly used by the Orthodox Church for Jesus’ mother. Mary’s title as “Mother of God” resulted from the work of the Third Ecumenical Council of Ephesus, 431 C.E., as early Christendom articulated what it believed about the human and divine nature of Jesus Christ. “What Mary bore was not merely a human being closely united with God—not merely a superior kind of prophet or saint—but a single and undivided person who is God and man at once.”5 Therefore, Mary’s high station in Christendom is derived from a belief in who Jesus is, a being divinely “conceived by the power of the Holy Spirit and born of the Virgin Mary,” as stated in the Apostles’ Creed. Because Mary was proclaimed by the Council to be the one who “contained the uncontainable God,” images of Theotokos are second only to icons of Christ in terms of “quantity and the intensity of their veneration.”6 Because Mary was solely human, her influence as spiritual model has identified her with common humanity more closely than any other person, something often dismissed in Protestantism as inappropriate or bordering on idolatry.

Questions concerning concepts of icon authenticity are especially relevant to Theotokos icons. Just as standards were established for determining authenticity of writings accepted in the canon of scripture, so also standards for determining authenticity of icons exist. One standard similar in both scripture and icons has to do with when the first images were produced and by whom. Images by those believed to be eyewitnesses are considered most authentic, thus the significance of Luke as the originator of Theotokos patterns. Tradition qualifies patterns as authentic, thus all subsequent icons are derivative of original patterns. This accounts for the similarity in features that render people recognizable despite being reproduced over hundreds of years by thousands of different artists. Icons not conforming to the essential qualities of established patterns would not be considered authentic.

The motivations and purposes for which icons are painted are also significant for discerning authenticity. Icons are to be God-inspired from the beginning. Iconographers are to be spiritually committed Christians capable of responding to God’s initiatives of guidance, even for choosing what to write. The willingness and ability of the iconographer to be a channel of God’s grace is a necessary link in connecting the icon with the viewer. The Orthodox Church believes that “real icons,” authentic icons that truly represent their prototype, hold a power for the believing or receptive viewer. This power that emanates from the icon is the major reason why icons are not to be used as decorator pieces in homes, unfortunately a current fad.

When icons are used as decorative art, they cease to function as icons. In fact, an Orthodox priest told me that icons lose their power when they are displayed in secular settings and are not respected for the purposes for which they were created. “Like scripture, when icons are removed from the ecclesial context of prayer and worship, you’re in big trouble!”7 The idea of receptionism comes to mind, the long-questioned idea that claims the power of the Eucharist resides in the beliefs of the individual receiver. The power inherent in authentic icons may be likened to the Real Presence of Christ in the Eucharist. Authentic icons are on a level of reverence equal to that of Anglicans’ respect for the consecrated elements of Holy Communion. Icons are not offered for secular displays any more than consecrated bread and wine would be left on a coffee table. A “real icon” carries the power to inspire and encourage the believer. It is the goal of every iconographer to be the instrument through whom God writes a revelation of truth.

The Power of the Most High Will Overshadow You

In the months before moving to Houston at the end of 2003, I anticipated there would be something special for me besides the new ministry job, some new opportunity that living in the city would provide. Soon after the move, I met a friend from our seminary years who told me he was learning to write icons and was discovering it to be a great way to study theology. As soon as he began telling me about his icon classes, I knew that learning about icons was the special thing I’d intuited would come to me. I called his teacher that same afternoon. Vivian accepted me as a private student, and we began weekly three-hour sessions in her studio. Enabled by Vivian’s professional skills as an iconographer, I completed my first icon, “Pantocrator,” within three months. That casual lunch conversation proved to be the catalyst for the processes that have reframed my theology and completely retooled my creativity.

During the months I worked with Vivian in her studio on my second icon, “Noli Me Tangere,” she encouraged me to practice at home writing any icons that attracted me. Using heavy water color paper instead of icon boards is an inexpensive way to practice mixing colors and painting the stylized facial features. One of my practice subjects was the “Theotokos” icon. I was attracted to her icon by the stunning beauty of her face surrounded by brilliant blue clothing, lavishly highlighted with gold.8 My practicing yielded unlovely lifeless faces and an inchoate sense that I was missing something essential in the process of icon writing. The beautiful face of Mary I’d failed to copy lingered in my thoughts, tugging at me.

It came to me one morning during my prayers that I should try again to write Mary’s face, only this urging seemed quite different than a practice assignment. There was a definite sense of feeling compelled, and two specific goals came quickly to my thoughts: First, I was to write it as a birthday gift for a friend who had a devotional relationship with the Blessed Mother; and second, Mary’s image had to be beautiful. Unlike my very unsatisfactory practice attempts, this effort was not for practice. It had to be beautiful, not to make it a more worthy gift, but because Mary was utterly beautiful and the assignment was to properly reflect her beauty.

The first goal felt completely arrogant. Who was I, less than a year into learning to write icons, to presume my friend, who had never expressed any interest in icons, would want to receive one from a total amateur? Prideful, indeed. Nevertheless, there was a sense, or maybe just a hope, that I was to create something sacred. Even if I managed that lofty feat, there was then the risk of its being rejected, a possibility that helped me comprehend another principal of icon authenticity. There is a powerful connection of the icon image with the person represented, and any reverence offered to the icon passes to the person depicted.9 An authentic icon is never about whoever produces it, so any rejection of the icon would be directed more toward the Blessed Mother than me!10

As for the second goal, my practice attempts verified how unlikely it would be for me to produce a beautiful image of Mary in the immediate future. The missing essential for writing sacred images had just been revealed to me: a response of trust in God was required of me if God was to enable me to fulfill what God assigned. Only in retrospect did I recognize this assignment as the beginning of a vocation. All I knew at the time was that I had to depend on the Lord in a way I had never even thought of before—to show me how to paint his beautiful mother.

Thus began a connection of contemplating divine assignments—Theotokos’ and mine. Certainly the one Mary received through the angel Gabriel’s announcement was the most profound divine assignment ever issued. Mary’s calling was the ultimate example of God choosing a human agent. Mine was far less significant, but just as personal and vital for my relationship with God. Maybe neither of us comprehended much about the implications initially, but we both wondered and questioned how this could be.

Gabriel’s explanation of how Mary’s child would be conceived has always seemed to me an unsatisfactory response to her legitimate question. “The Holy Spirit will come upon you, and the power of the Most High will overshadow you; therefore the child to be born will be holy; he will be called Son of God” (Luke 1:35). Gabriel’s explanation was proclaimed to answer what I had assumed was Mary’s question about biology. A common mistake of Bible readers is asking questions of a scientific or historical nature and expecting answers that reflect the asker’s mindset rather than the Bible’s purpose. The Bible is stubbornly prone to giving theological and spiritual answers instead, a plane I had never before perceived in criticizing Gabriel’s explanation to Mary. Regardless of the nature of Mary’s question or my appraisal of Gabriel’s explanation, a faith response was required if God’s assignment was to be fulfilled. Regardless of magnitude comparisons, a response of trust in God was called for from the Blessed Mother, and from me.

The misguided approach to scripture just described can also yield misunderstandings about the Doctrine of the Virgin Birth. I have accepted as essential the theological truth of the doctrine while choosing to relegate my biological questions to the unanswerable “Mysteries of God” category. While I cannot pretend to have unraveled the twist we’ve gotten ourselves into about this doctrine, being confronted by the icon of Theotokos and the assignment to write her image has brought me closer to what feels like a better understanding. Rather than intending to say anything about the physical nature of Jesus’ conception, what if the Doctrine of the Virgin Birth is exclusively a theological statement? If so, have my mistaken assumptions ignored possible theological or spiritual meanings of virginal status that have nothing to do with Mary’s physical status? Could mistaken assumptions have stunted my responses to God’s initiatives? Have I missed other opportunities, other times God has called me, because I failed to comprehend the absolute adequacy of theological explanations? Scripture says Jesus was not the only one who was conceived apart from the physical initiative of man. “But to all who received him, who believed in his name, he gave power to become children of God, who were born, not of blood or of the will of man, but of God” (John 1:12–13). Are not all spiritual births the result of some sort of virginal conception, that is, without the aid of a physical human father? Are we not all born again by the Holy Spirit coming upon us and overshadowing us by the power of the Most High?

The Incarnation of Christ was the real physical manifestation of the creative power of the Holy Spirit. Mary’s cooperation with being overshadowed by the Most High was essential if a virgin conception (a better designation than virgin birth) was to occur. Likewise, our cooperation and participation are required if Christ is to become incarnate in us. As new creations in Christ, our rebirth is physically manifested through actions that reveal renewed, transformed people, people who look somehow different than before. This is the deification process Orthodox theology says is nothing less than our salvation and redemption.11 Spiritual rebirth is supposed to show!

Orthodox theologian Leonid Ouspensky said, “If the icon of Christ, the basis for all Christian iconography, reproduces the traits of God who became man, the icon of the Mother of God, on the other hand, represents the first human being who realized the goal of the Incarnation: the deification of man.”12 Mary’s beauty is iconic language that presents her deification. Anatomically incorrect for emphasis, her facial features represent four of the five senses, doors of access to God. Disproportionately large eyes have seen holy things. Her abnormal-looking ear is tuned to hearing the Word of God. Her long, thin nose has smelled the fragrance of holy things. Her lips are closed, representing the gentleness of few words, and the small mouth indicates that only a little food is needed. The blue of her garments represents purity. Vivid splashes of gold marking the folds of her garments emphasize the brilliant light of God that shines from within her. Mary’s complete deification accounts for the beauty of her physical appearance. If I didn’t eat so much or talk so much, if my eyes were always wide open to the presence of God, if my ears were filled more often with the music of heaven instead of the noise of the profane, then maybe the...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Icons Found in This Book

- Preface: Drop by Drop, the Puddle Is Refilling

- Introduction: Eyes to See: The Redemptive Purpose of Icons

- Part I Discernment ~ Receptivity

- Part II Fulfillment ~ Embodiment

- Further Words—Four Questions

- A Final Word

- A Brief Guide for Individual or Group Meditation of Icons

- Appendix: Parallel Processes: The Descent from the Cross—Removal of Artificial Life Support

- Acknowledgments

- Notes