- 96 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

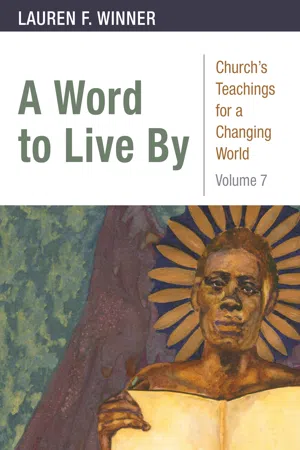

A Word to Live By

About this book

- Next generation of the classic Episcopal Teaching Series

- Accessible and engaging enough for newcomers and adult learners; full of content for church leaders and seminarians

- Filled with interactive study materials

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

What Are We Talking about When We Talk about “The Bible”?

At any Episcopal worship service, you will hear passages from the Bible. What, exactly, is the text from which we read in church? In this chapter, I’ll try to answer that question by walking backwards, charting in reverse order the history of the biblical text.

When you hear the Bible read in an Episcopal church, you’re usually hearing passages from the New Revised Standard Version of the Bible (often called, simply, the NRSV). That’s a recent English translation of texts originally written in Hebrew, Aramaic, and Greek. The NRSV was published in 1989; it was produced by a group of scholars—mostly members of Protestant churches, though there were a few Catholic and Orthodox Christians, and one Jew. Their task was to update a 1952 translation of the Bible, the Revised Standard Version (RSV). In their work, which began in 1974, the NRSV translators set out to draw on the latest in biblical scholarship. They also wanted to update any passages that, because American idiomatic English had changed so much since 1952, sounded stilted to the 1970s ear, and they wanted to get rid of unnecessary masculine pronouns and to eliminate the words “man” and “men,” if the Greek or Hebrew versions of those words didn’t actually appear in the original (so the RSV’s rendering of Matthew 6:30, “O men of little faith,” became “you of little faith,” and the RSV’s “Man does not live by bread alone” in Matthew 4:4 became “One does not live by bread alone”).

Every new Bible translation has disgruntled critics. When the Revised Standard Version of the Bible was published in 1952, one minister in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, deemed the new translation “a heretical, communist-inspired Bible.” He burned a copy with a blowtorch and sent the ashes to Luther Weigle, who’d chaired the translation committee.

The NRSV is by no means the only English translation of the Bible; on my bookshelf, I have nine different English translations, and even that is a small fraction of what’s available. The Episcopal Church has authorized fourteen different translations for use in our worship services, but typically we read the NRSV. Most of the translations that Episcopalians can use in corporate worship were published in the last sixty years, but one is much older: the King James Version of the Bible (KJV), which was first printed in 1611, and which in some way stands behind all subsequent English translations. The King James was not the first English Bible—it was in part because there were so many different Bible translations floating around England at the beginning of the seventeenth century that James called for a new translation. (James hoped the new translation would be authoritative; he also hoped it would replace the popular Geneva Bible, whose interpretative notes contained anti-monarchical sentiments.) It took several decades for the KJV to become established as the principal Bible in England; once it had, the KJV also began to predominate in the English colonies in North America.

So, we have a range of English translations—of what? Just what are these English texts, from the King James to the New Revised Standard Version, versions of?

The book known as the “the Bible”’ is in fact a collection of over sixty books, which were themselves written over the course of perhaps one thousand years. We know with some confidence who wrote some of them (Paul’s letter to the Galatians), and we don’t know the authorship of others (the Psalms). It’s long been thought that some material in the Bible was in circulation orally for many years before being written down; other biblical material was, in its first instantiation, a written text. By “books,” I mean literary works with notional independence. A given biblical book was not necessarily written by one person, or even written at one time (Dorothy Sayers’s novel Thrones, Dominations was completed after Sayers’s death by Jill Patton Walsh; thus it has two authors, but it is one coherent work).

Over several centuries, early Christians discerned which books would constitute, and hold the authority of, sacred Scripture. The earliest Christians inherited—and continued to study and read in worship—Israel’s Scripture, which comprised three sections: the Torah, the Prophets, and the Writings.

• The Torah—the five books of Moses—tells the story of the creation of the world, and God’s relationship with humanity, focusing in particular on God’s relationship with the descendants of Abraham and Sarah. The Torah follows those descendants, the people of Israel, into and out of slavery, and through a forty-year period in which they wandered in the desert, received a revelation of law from God, and made their way to the edge of the land of Canaan.

• The Prophets are collections of oral declamations by people chosen by God to speak to the people of Israel, to interpret their present to them, to remind them to keep God’s law, and to chart a vision for their future.

• The Writings encompass poems, prayers, proverbs, narratives about individual men and women’s faith lives, and histories.

The Torah, the Prophets, and the Writings were originally written in Hebrew and Aramaic. By the time Jesus was born, various Jewish communities had translated the Hebrew and Aramaic texts into Greek, the dominant language of politics, trade, and learning in much of the Mediterranean world. The earliest Christians read these Greek translations alongside Hebrew and Aramaic texts of the Jewish scriptures, especially as the church spread among Jews and Gentiles for whom Greek was a mother tongue. (By custom, these various Greek translations of scriptural books are referred to as the Septuagint. The term “Septuagint” comes from the Latin for “seventy”; the term was applied to the Greek Jewish scriptures because it was thought that 70 Jewish scholars translated the books of Moses into Greek in Alexandria some time in the third century BCE.)

As the first Christians were continuing to read and study Israel’s Scripture, they were also producing their own literature and reading it in church. Letters of theological instruction and practical counsel, written by Paul of Tarsus, circulated throughout the churches, and Gospels (accounts of the events leading up to and following the death of Jesus of Nazareth) began circulating, and other texts circulated, too. By the middle of the second century CE, Christians began discerning with focused intentionality which of these new texts should be read in church worship and studied in church. They were trying to clarify which letters and Gospels Christians absolutely needed to read, which texts Christians urgently needed to converse with, and which texts could confidently be known to convey the words of God to God’s people.

That discernment entailed real debate. In particular, there were arguments about whether to include the epistle to the Hebrews and the Revelation of John of Patmos. These arguments turned largely on three questions.

1. Early Christians asked whether the content of the books was consistent with what they knew about God.

2. They were also interested in who had written the text—was it written by someone who had witnessed personally the events he was writing about, or who was otherwise deemed a trustworthy reporter?

3. And finally, early Christians wanted to know whether there was consensus among Christian communities that a given book was life-giving, inspired, and inspiring. Did Christian communities generally agree that a book helped their faith grow and helped them follow Jesus? St. Jerome, for example, said that it didn’t much matter that no one knew who wrote the letter to the Hebrews, because the letter was “constantly read in the churches.”

By the end of the fourth century, the churches in the Roman Empire had settled on the books that they understood to be the words of the Lord and therefore to be read in church and studied for interest and edification. To the Jewish scriptures, the church had added the Gospels according to Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John; a text called Acts of the Apostles, which recounts the ministries of several early Christians who were crucial in spreading the story of Jesus throughout the Roman Empire; twenty-one letters; and the Revelation of John of Patmos. (They’d settled not only on which texts to embrace as Scripture; they’d also affirmed the importance of the order I just gave, the same order you’ll find in the table of contents of any New Testament today.)

PAUSE AND CONSIDER How do you respond to this history—to the Bible’s comprising a collection of books written over many centuries, whose status as “biblical” required discernment and debate?

The early Christians’ long discernment concluded the process of canon formation, and the books finally included in the small library we know as the Bible are called the biblical canon. It’s a basic component of Christian faith to think that the Holy Spirit worked through the early Christians in this process of canon formation. The church has always affirmed that Christians can read, and expect to be spiritually edified and theologically nurtured by, books that aren’t included in Scripture. But Scripture alone is the text we proclaim in worship and respond to in sermons. And Scripture alone is the text about which Christians say “these are the words by which God speaks directly to us.”

Canons are, it must be admitted, somewhat out of fashion. Fifty years ago, it seemed to people that there was a clear “canon of Western literature” and “canon of Western art.” Today, not only the scope of those canons is debated; the very sense that we can meaningfully talk about a canon of Western literature, or should want to, has been usefully subjected to scrutiny by people who are interested in giving Tabitha Tenney’s 1799 novel Female Quixotism (a novel I adore) or Harriet Jacob’s 1860 autobiography Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (which I read annually) the same attention they accord Moby-Dick.

Roman Catholic editions of the Bible have seventy-three books; all Protestants, including Episcopalians, include only sixty-six. The extra (or, depending on your perspective, missing) books were included in some, but not all, ancient Jewish collections of Scriptures. In antiquity and the Middle Ages, Christians understood the books in question to be part of the Bible, even as there were learned Christians who questioned their status because the books were not included in all Jewish scriptural collections. During the sixteenth century, Protestants affirmed that (in the phrasing of Martin Luther) these books “are not held equal to the Sacred Scriptures and yet are useful and good for reading,” while Catholics affirmed the books as “sacred” and canonical. The Episcopal Church acknowledges them as (in the words of one sixteenth-century Anglican) “read for example of life and instruction of manners,” and we occasionally read passages from some of them—Judith, Baruch, Sirach, and the Wisdom of Solomon—during worship.

So why a biblical canon? I sometimes chafe against our canon. I think it would be interesting to preach on one of the gospels that was excluded from our biblical library, and there are bits of Ezekiel and Ephesians I’d like to skip. But I believe that, just as Jacob wrestled with the angel and was eventually blessed by his wrestling (Genesis 32:22–31), the task given to us by the early church’s canon formation is a task of committed wrestling. I needn’t understand or enjoy or feel affinity for all of Scripture—but I’m committed to wrestling with it, and I believe that eventually, I’ll be blessed by that wrestling (though I also think the wrestling might leave me, as it left Jacob, limping).

In my canon-wrestling, I sometimes muse about etymology. “Canon” comes from the Greek word for “rule.” The Greek word is a Semitic language word adopted into Greek; the Semitic word means “ruler” or “measuring rod,” and it, in turn, comes from a Semitic root that designates a “reed”; that root is etymologically related to “cane,” as in sugar cane. Historically, the reason we began to call the books of the Bible our “canon” is that the list of canonical books constitutes a rule for our reading, and the books in question constitute a rule of faith. No one was thinking about sugar cane when they began to speak of the biblical canon. But I like to think of it. Sugar cane has a complicated history—its history in the West is inseparable from the history of slavery, and the history of poverty in the Caribbean. There’s a bitterness to sugar cane, just as there is bitterness to how biblical texts have, in history, sometimes been used to violent ends.

But sugar cane, like the canon, is sweet. In the words of the Bible itself, “How sweet are your words to my taste, sweeter than honey to my mouth” (Ps. 119:103).

PAUSE AND CONSIDER Scripture brims with similes, metaphors, and other flights of prose that help us see what kind of book Scripture is. According to various biblical books, Scripture is a lamp, a running path, a blanket of snow on the landscape, a mirror. Which of these metaphors intrigue you? If the Bible is a running path, where does it lead? If the Bible is a mirror, what should we expect to see when we read the Bible?

Chapter 2

Digesting Scripture

If you attend an Episcopal church on the second Sunday of Advent, you’ll pray a collect that focuses, in a seasonally appropriate key, on Jesus’s coming, two thousand years ago, “to visit us in great humility,” and on anticipating Jesus’s second coming, “in the last day.” But in the sixteenth century, Anglican worshippers who used the first edition of the Book of Common Prayer (it was published in 1549) found a different collect for the second Sunday of Advent.

The collect said at the beginning of a Sunday service is a short prayer that collects the themes of the day’s worship service.

Their collect was connected not so much to the grand themes of Advent, but to the reading from the Letter to the Romans appointed for that Sunday. In that reading, Paul assures the fledging church in Rome that Scripture “was written in former days . . . for our instruction, so that by steadfastness and by the encouragement of the scriptures we might have hope” (Romans 15:4). The collect that people prayed a few minutes before hearing those words is now known as “the collect for Scripture.” In the pra...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface: An Acquired Taste

- Chapter 1:

- Chapter 2:

- Chapter 3:

- Chapter 4:

- Chapter 5:

- Chapter 6:

- Chapter 7:

- Conclusion: Abundant, Inexhaustible

- Acknowledgments

- Notes

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access A Word to Live By by Lauren F. Winner in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Christian Denominations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.