![]()

1

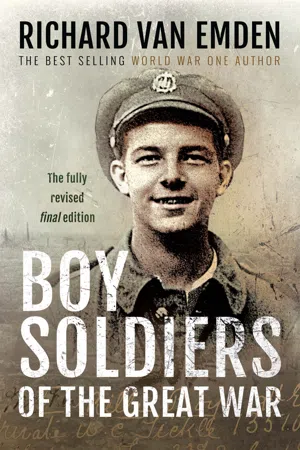

Youthful Dreams

ONLY A BOY BUT A HERO

4214 Private Frank Grainger,

16th Battalion Australian Infantry

Killed in Action 30 August 1916, aged 17

Patriotism was not universal in early twentieth-century Britain, but most people did not question their lifelong allegiance to their native land. Communities demonstrated this through popular activities such as pageants and processions, celebrating the continuing prosperity of the nation and its empire.

On a more personal level, newborn children were often given names that reflected the nationalism of their parents – George Baden White, for example, was born in August 1900, the son of a gunner serving with the Royal Garrison Artillery in Malta. Thomas White, his father, was a patriotic man and, in choosing names for his son, he turned to military leaders made famous in the Boer War. Sir George White, holder of the Victoria Cross, successfully defended the South African township of Ladysmith until its relief in February 1900; Colonel Robert Baden-Powell, better known now for founding the Scout movement, similarly defended Mafeking until relieved in May. Across Britain there had been wild public celebrations at the news and both became national heroes. So the choice of names for the newborn baby sleeping soundly on the island of Malta was obvious: George and Baden.

At least 5 per cent of children born in 1900 were given names associated, in one way or another, with the Boer War. After May, and for the next year, over 6,100 British children, mostly boys, were christened Baden and another 1,000 Powell. A few parents went further, christening their children Mafeking Baden or Baden Mafeking. In England alone, over 700 children, both boys and girls, were christened Mafeking, and over 800 girls were called Ladysmith, or after the other besieged town of 1900, Kimberley, while Pretoria was the chosen name for 600 girls and over sixty boys. Even General Sir Redvers Buller, vc, who, as commanding officer in South Africa, oversaw many of the war’s military failures, had nearly 7,300 British children named after him, either Redvers or Buller; while in 1900, another 3,000 children were named Roberts, after Field Marshal Lord Roberts, vc, the man sent to replace him. Almost any name in South Africa mentioned in the press found its way into baptismal records, from Modder River Lampard to James Spion Kop Skinner. Thirty-five unfortunate children grew up with Bloemfontein inserted in their names; thirty-four had Majuba; fifty-four had Transvaal; and six the name of Stromberg. One child, born with the surname of Russell on 14 April 1900, was even christened Baden Powell Brabant (after the noted Colonial cavalry regiment serving on the veldt) Plumer (after the British general) Mafeking. If that was not enough, Baden later claimed Ladysmith as part of his name, though baptismal records do not support this.

No one came more highly respected than the Queen herself. The names Victoria and Victor became fashionable; ‘Victoria’ was fourteen times more common in 1897, the year of the Queen’s Jubilee, than in 1896. The word ‘ jubilee’ itself was given too, if not as a first then as a second or third name. Bertram William Jubilee Rogers was born during the fiftieth anniversary of the monarch’s accession to the throne in 1887; James Jubilee McDonald was born during the Diamond Jubilee celebrations ten years later. Both were killed during the Great War.

Adult patriotism permeated down to children. At school, headmasters noted famous days in the military calendar, such as the Battle of Waterloo or the defence of Rorke’s Drift, and children stood in respect. The portraits of great military commanders adorned school walls, along with explorers and adventurers, men to be admired, respected and emulated. Tangible expressions of patriotism may seem outmoded today but, for a great number of boys, young life was steeped in military glory and the great campaigns of the past.

A few of the children who would serve underage in the Great War could just about recall the joyous, Union-Jack-waving behaviour of adults during the Boer War, when Mafeking was relieved and a school holiday granted. They remembered, too, the national sorrow at the Queen’s death in 1901, when children wore black as a mark of respect. Her birthday, 24 May, was celebrated as a public holiday during her lifetime and from 1902 as Empire Day, a manifestation of pride in the nation’s achievements. In schools up and down the country, the day was rigorously observed: children turned out to parade banners on promenades and in parks, as brass bands played and local dignitaries made rousing speeches. George Baden White, who arrived in England in 1901, saw it all:

Each year we had a pageant. That was Empire Day, and most of us really revelled in it. The pageant consisted of somebody appearing as Britannia as the centrepiece, and the boys representing the major colonies, like Australia, Canada, New Zealand and South Africa, paying homage to her. As part of the proceedings, we all wore either a red, white or blue cap, lined up to form the Union Jack, and, of course, finished up singing the National Anthem. I loved every minute of it.

This was a world in which monarchy, Church and army were fused together in impressionable minds as the bulwarks upon which the nation state’s security, peace and prosperity rested, each integral to the others’ survival. The Boy Scouts’ three-fingered salute expressed this ideal, representing service to God, King and Country.

The Scouts were one of a number of uniformed youth organisations formed in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, helping to promulgate, perhaps to engineer, future social cohesion; others included the Boys’ Brigade and the Church Lads’ Brigade. All offered boys a taste of outdoor adventure within a framework of healthy Christian discipline and obedience.

Thousands of young boys joined the Scout movement when it was formed in 1907, benefitting from activities that encouraged cooperation as well as self-reliance, personal discipline and fun. The organisation professed not to encourage militarism and to an extent this was true. The elementary drill that the boys practised was said to be similar in character and purpose to that undertaken by children in a school playground so that they could move in numbers without misunderstanding or delay. The long list of badges, of which there were about a hundred, was held up as another example, for few could be associated with military training. Yet the essence of Scout training was self-government, self-discipline, loyalty and good citizenship, and all these had military applications. Boys were taught to march, wave banners, and win medals. They were taught camping, signalling, tracking; they learnt first aid, Morse code and semaphore. In camp, they frequently slept in bell tents and deployed sentries; they built fires and cooked, and in the evening they sang songs:

Scouts will be Scouts

Scouts can be heroes too

By striving to aid

A man or a maid

And seeing the Scout law through.

The Scouts’ motto ‘Be Prepared’ was very pertinent, as war with Germany was anticipated. Since the 1880s, Germany’s industrial rise had been meteoric. As a nation, it had been founded in 1870 and led since 1888 by Kaiser Wilhelm II, a grandson of Queen Victoria. The Kaiser, envious of Britain’s empire, was an enthusiast for rapid industrial and military expansion, leading his country into a naval arms race with Britain that only fostered mutual suspicion. Britain was well aware of the threat of an increasingly strong German nation, and the expectation that war might one day break out between the two seeped into the public consciousness through books and newspapers.

Britain relied on the navy to impose her will and defend the home country. The conflict in South Africa threw into sharp relief the difficulties of fighting a war ranging over thousands of miles, and it had been fought at a time when Britain’s pre-eminence was beginning to ebb. Security through alliances would have to be the way forward: Britain entered into agreements, first with Japan in 1902, and most notably with France in 1904. These ententes were significant because they were, in effect, an acknowledgement that in a changing world Britain would have to cooperate with other nations if she were to maintain her empire.

No country wanted to join an unnecessary war, but understandings with nations such as France ensured that if a major conflagration broke out, Britain would probably side with her neighbour. This likelihood was increased when Britain concluded an Anglo-Russian convention in 1907, as France and Russia were already in alliance. These agreements safeguarded the Empire, but Britain had been drawn into European affairs to an extent that would have seemed impossible a generation before. The only country in Europe with whom Britain might come to blows was Germany, and in this case no non-aggression pact of any sort was attempted. When Germany invaded Belgium in August 1914, Britain had reason to go to war, not because she treasured that country’s neutrality, but because it was in her national interest to side with France and Russia.

The imminence of the conflict in no way hindered the recruitment of youngsters who, if anything, could now see the possibility of military glory won fighting for their country. If the Scouts or other boys’ organisations did not deliberately act as a fertile recruiting ground for the army, their culture of ‘good citizenship’ certainly encouraged such ideas, and prepared their members for active work.

For boys interested in a direct route to an army career, there was Boy Service. Lads signed on from school as young as thirteen, or, if they were the sons of serving soldiers, from the age of twelve, and were predominantly trained to be drummer boys and buglars, and taught trades such as tailoring. Over 2,500 such boys were serving at home or in the colonies by 1914. They received 8d (eight pence) a day until the age of eighteen, when they became soldiers proper, receiving half as much again in pay. This automatic jump in wages was a clear incentive for others, those aged sixteen or seventeen, to inflate their ages on enlistment.

Britain’s Regular Army was small by European standards. Reliance, perhaps over-reliance, on the Royal Navy to defend the nation’s sovereignty had allowed the army to remain purely professional, with, in all, about 250,000 men, half of whom were stationed overseas, and a reserve of a further 225,000 former soldiers who had returned to civilian life but were available in a national emergency.

Across Britain the military provided an ever-present backdrop to daily life in large swathes of the country. In ‘army’ towns, such as Winchester in Hampshire and Richmond in Yorkshire, there was a high concentration of military personnel regularly witnessed on manoeuvres. Keen country boys were offered opportunities to watch the soldiers at summer camp, to walk alongside as the men tramped country lanes, or help look after horses in the transport lines. One boy from Hartlepool recalled:

These bronzed infantry soldiers marched through the village with packs and rifles on long route marches. They went down into the Dene and up the other side of the valley to Nesbit Hall and disappeared into the distance, while we awaited their return. When they came back, their shirts were open at the neck and they looked really exhausted and we offered to carry their rifles. Then, if we were allowed to do so, we made our way up to the camp where the soldiers were making full use of the Ship Inn and there was a lot of singing going on. It looked very romantic with the field kitchens going, preparing the meals, and the smell of the food, the smell of the horses in the lines, the jingle of the harnesses and the bits. It made a fourteen-year-old boy long to be a soldier.

There were always boys who were destined to join up, like Benjamin Clouting, the son of a groom working on a large Sussex estate, who volunteered in 1913 at the age of fifteen.

As a child I brandished a wooden sword, with red ink splattered along the edges, and strutted around the estate like a regular recruit. I daydreamed about the heroic actions of former campaigns, and avidly read highly charged stories of action in South Africa.

Ben had close family links to the army. He had two uncles, one of whom served in the 11th Hussars and taught his young nephew to ride ‘military style’, while the other, Uncle Toby, served in the Scots Guards.

He was a great character and a sergeant major. Even though he had been too young to fight in South Africa and later somehow avoided the First World War, he nevertheless nurtured my interest in the army.

When it came to war and death, the experience of childhood in the early twentieth century was different from that experienced a hundred years later in one way in particular: today’s children are graphically exposed to images of war but protected from the effects of death; Edwardian children were well aware of death but largely naïve about the effects of war.

The Victorian ‘culture of death’ was well developed and continued up to the Great War, with children being encouraged to take an active part in death rituals such as wearing black and kissing the hand of the departed. The sight of a body was not unusual, the dead often resting in an open coffin at home before the funeral. Illness was rife and contagious diseases hard to control when so many families lived in cramped, back-to-back houses, in insanitary conditions. With infant mortality high – 20 per cent of children failed to reach their fifth birthday – it was common to lose a sibling. Overall life expectancy was around fifty for men and slightly higher, fifty-five, for women, and so the loss of a parent or other near relation in childhood was unremarkable. George White lost his father by the age of five, but that was far from his only contact with death. During his childhood, George lost a cousin, Ernie, killed playing on a railway line, and a school friend named Sutton, who drowned in a creek, while a Scoutmaster was accidentally killed during camp. In addition:

A pal of mine, Theobald, lost his mother, who died from consumption, and a neighbour in our road, named Stevens, was killed in an explosion in one of the powder mills.

Death was commonplace but the effects of war less so. Britain’s colonial conflicts were described but not seen, drawn but barely photographed. The medium of film, still in its infancy, was capable of taking anodyne images of soldiers fording a stream, or baggage trains crossing the South African veldt, but nothing of the actuality of fighting. A combination of unwieldy cameras and the restrictions of public taste ensured that explicit war cinematography would wait another generation. Instead, war artists drew the conflict, presenting stirring scenes of battle that were never ignoble. The effect was to create a generation of war romantics. Thomas Hope, who was to serve in France aged sixteen, remembered:

War, glorious war, with its bands and marching feet, its uniforms and air of recklessness, its heroes and glittering decorations, the war of our history books … From the cradle up we have been fed on battles and heroic deeds, nurtured on bloody episodes in our country’s history; war was always glorious, something manly, never sordid, uncivilized, foolish or base.

When the war broke out, ‘the height of my ambition’, he wrote, ‘was to fight for King and Country’.

Stuart Cloete was as intoxicated. He was not much more than three years old when he saw a black and white drawing in his father’s copy of the Daily Telegraph. It was the time of the Boer War, and the image, as Stuart recalled, was:

of a boy trumpeter with a bandaged head, galloping madly through bursting shells for reinforcements. My father coloured the picture for me. The horse brown, the boy in khaki with a red blob of blood on the white bandage round his head. The picture was hung in my nursery.

Stuart was raised on the stories of ancestors who had served, including his great-great-uncle who, at the age of fifteen, fought at the Battle of Waterloo. As a child, he played with hundreds of lead soldiers and guns and forts, and read books with titles such as Boy Heroes and Heroes and Hero Worship as well a...