![]()

PART I

FORGING A NEW IDENTITY

![]()

CHAPTER 1

POLITICAL CAPITAL

In a laudatory article that appeared in the government-issued multilingual propaganda publication La Turquie Kamaliste, an American journalist who visited Turkey’s new capital in the late 1930s observed:

Ankara is a city built by the people of a living generation—by Atatürk and his followers. They wanted and they have a capital, an absolutely new city which would symbolize the breakaway from the old and which would demonstrate to themselves and to their visitors what can be done in a hitherto backward Turkey. . . . It isn’t just this giant city that makes us feel that this is Atatürk’s city. Ankara embodies the spirit of the new Turkey about which we have read so much but find hard put to find in Istanbul.1

Indeed the founding fathers of the republic considered building a new capital in Ankara to be integral to their twin goals of modernizing the country and forging a new political order. They fervently believed that producing a new built environment that physically and metaphorically stood apart from that of its Ottoman predecessor and provided a model site for enacting the modern way of life and reaffirming the new cultural values would lend their revolution a tangibility that discourse alone could not.2 Beyond a mere change of address for the seat of power, building a new capital provided an extraordinary opportunity for inscribing the structural transformation of the state into the physical landscape. Therefore, although this gargantuan enterprise threatened to drain Turkey’s already scarce human and material resources, the nationalists seized on its cathartic quality. If starting from scratch entailed years of severe hardship, it also afforded them a unique chance to articulate a new beginning.

The making of Ankara was riddled with challenges: Turkey’s new leaders lacked the social or physical planning expertise needed to define or implement such a complex and comprehensive undertaking. Their widely divergent ideas about a modern capital that could measure up to its Western counterparts were based on fragmented recollections of personal visits to European capitals rather than a systematic understanding of the structure and organization of these cities, their historical development, or their problems. They were also under tremendous pressure to build quickly, as Ankara had neither sufficient office space to accommodate basic government functions nor enough housing for the unprecedented influx of people whose arrival pushed the population from 20,000 in 1920 to 74,000 in 1927 and to 125,000 in 1935.3 Furthermore, the competing needs and interests of the local population and the incoming groups pulled the process in different and often incompatible directions. Consequently, initial planning and construction efforts were largely uncoordinated and consisted of sporadic attempts to solve discrete problems. As Geoffrey Knox, the chargé d’affaires for the British embassy, put it, urban expansion was rapid and haphazard:

Every effort is being exerted with a fine disregard for expediency—even of possibility—to make of Angora the strategic, economic, social as well as the political center of the country. . . . Banks spring up like mushrooms on an ever larger and imposing scale, but all with an equally imponderable capital. Houses, shops and villas are built in every direction with no coherent plan in a wave of optimistic speculation. New roads are traced and abandoned after a spell of feverish and expensive work in order to seek another alignment suitable to some man of influence, or, if they reach completion, subside in a few days under the stress of modern traffic. The municipality undeterred by chronic bankruptcy, goes from one grandiose project to another, each more wasteful, incoherent and inept than the last.4

Ankara’s built environment provides a fertile ground for examining the untidy process by which republican ideals of a modern urban life and a new political culture were translated into action—and not least because so much had been invested in it symbolically, materially, and politically. Probing the discrepancies between the verbal and visual rhetoric used to promote the making of Ankara and actual events on the ground reveals how expediently malleable the nature of modernization discourses and practices were under the republican regime. Similarly, examining the still visible traces of tentative beginnings and altered or abandoned schemes in the city’s physical fabric reveals evidence of manifest resistances, rival interventions, and conflicting intentions. In short, when Ankara and its representations are seen through this forensic lens, what was discarded becomes as informative as what was implemented and what was highlighted becomes as telling as what was downplayed.

This chapter focuses on two sites that are especially symptomatic of the divergent forces that shaped both the physical form of Turkey’s new capital and its form of government. The first of these is the Citadel and its immediate vicinity, which constituted the town of Ankara until the arrival of the nationalists to set up the wartime headquarters for the post–First World War struggle for national liberation. Although the nationalist leadership invoked the imperative to modernize as the primary driver of their decision to relocate and purge all social, institutional, and spatial vestiges of the Ottoman Empire, the pliable logic by which they physically and rhetorically repositioned the existing town betrayed other more pragmatic—and often self-serving—calculations. The second site is the North-South axis, which became Ankara’s main artery, radically transforming the town’s morphology. Although the artery was to be punctuated with a sequence of memorials replicating the milestones of Turkey’s journey from its grassroots independence struggle to democracy, halfway into the implementation the Presidential Palace replaced the Grand National Assembly as the culmination of that narrative. Far from being accidental, this shift paralleled changes in the political regime, which was fast veering toward authoritarianism. I argue that the intertwined stories of these two sites, taken together, hold clues to broader questions about the nature of political authority in the modern Turkish state and the fraught relationship between the country’s ascendant Westernized elites and its population at large.

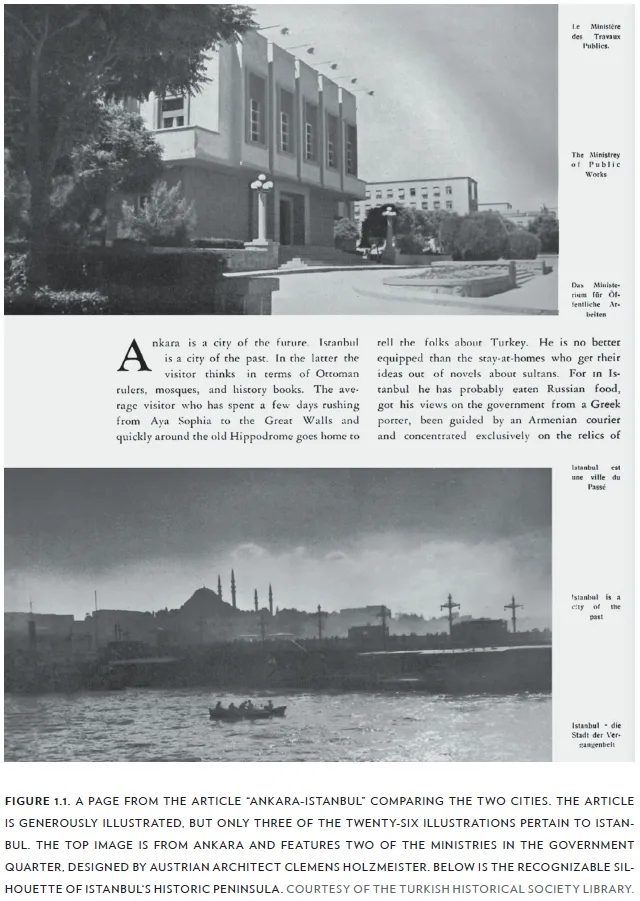

JUSTIFYING THE MOVE

In the early years of the republic, the nationalist intelligentsia used two complementary tropes to justify the decision to relocate the capital in Ankara. The first of these was a logical extension of the ubiquitous and overarching binary discourse that pitted the Ottoman against the republican order to posit the virtuous achievements of the latter over the failures of the former. Using Ankara and Istanbul—two actual places—to illustrate the differences imparted the comparisons a degree of concreteness that sheer words could not attain. In this ever-expanding verbal visual repertoire of contrasts, Ankara became the embodiment of patriotism and progress, whereas Istanbul was assigned the negative mirror image of these qualities, perfidy and obscurantism. The second trope was the equally persistent myth that Ankara had, miraculously, been built from scratch by the idealist founding fathers of the republic. The home base of the nationalist revolution was now an exemplary capital that was transforming Anatolia’s barren plains. Both tropes were widely disseminated through all the means available to the government, in textbooks, newspapers, traveling movie screenings and exhibitions, songs, posters, and speeches. Both masked inconvenient incongruities and pragmatic considerations that would otherwise undercut the image of unmitigated idealism carefully maintained by the republican elite.

In their efforts to validate their actions, the nationalists indiscriminately targeted every aspect of Istanbul and, by implication, the Ottoman legacy it represented. They were critical of the city’s location, tucked in the northwestern corner of the country, too far away to hear people’s concerns or attend to them in times of need. Yet another cause for concern was the leverage European states had gained in Ottoman politics, mostly through liaisons cultivated with powerful palace officials and bureaucrats since the eighteenth century. They also had substantial reservations about Istanbul’s susceptibility to unchecked foreign influence because it was a major port city with a cosmopolitan population. In particular, they regarded the city’s predominantly non-Muslim merchants as agents of imperial capitalism whose ventures with European merchants and manufacturers had been detrimental to the national economy and industry. The nationalists were aware that these networks had not necessarily dissolved following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire and remained a serious threat to achieving full sovereignty. Summarizing these concerns in debates at the Grand National Assembly, which led to the proclamation of Ankara as capital, Representative Besim (Atalay) passionately argued that “places like Basra or Erzurum could not be responsibly governed from such a distance.5 Istanbul, as he put it, was more like a colonial capital “like Congo, like Calcutta, like the colonial capitals of Indochina” rather than a self-selected capital.6 Finally, the nationalists saw the Ottoman administration as a tenacious roadblock to Turkey’s embrace of modernity, and Istanbul itself as the symbol of that stagnation. Not only had the Istanbul government “surrounded itself with a Great Wall of China” cutting itself off from the rest of the country, posited the semiofficial daily Hakimiyet-i Milliye, but it had also managed to “isolate Anatolia and the people of Anatolia from the rest of the planet, from the Enlightenment of the civilized world until now.”7

Therefore, the nationalists reasoned, the relocation of the capital and returning to the “bosom of the nation” (sine-i millet) was a vital course correction to safeguard the country’s future and protect it from infringements on national sovereignty.8 Their conviction that there was an active and mutually reinforcing relationship between state, space, and the formation of a new and modern national identity crystallized during the negotiations for funding Ankara’s construction at the GNA.9 Despite the disproportionate investment it would require, they argued that “building a government seat worthy of an advanced state, by outfitting it with the necessary infrastructure, sanitary and scientific dwellings, and other essentials of civilization is one of the most vital duties of our government as authorized and sanctioned by the Grand National Assembly.”10 The making of Ankara was frequently equated with Turkey’s efforts to “join civilized nations marching forward on the path of progress,”11 which was bringing the country in line with Western civilization and, in the republican imaginary, figuratively moving it closer to Europe. In an article that celebrated this very metaphoric proximation, the popular weekly Yedigün declared: The construction of Ankara has effectively transformed the map of Europe. We can now claim that Europe starts in Ankara. Was this not the purpose of our revolution?12

Nevertheless, becoming modern on these terms also implied an inherent subjugation to Western hegemony, which Turkish nationalists had aimed to break in the first place.13 Constructing an “other” that could be pushed back to a permanent state of anteriority was a theme borrowed from post-Enlightenment notions of history and progress. It had been very effectively deployed by European powers to legitimize capitalist expansion and colonialism that had also been so detrimental to Ottoman interests. These (now extensively criticized) schemes were predicated on an essentialist divide between the West and the rest, implying that not only past societies but also all living ones could be located within a one-way timeline, the trajectory of which was determined by Western civilization.14 Perceived distinctions between Western and non-Western cultures were thus construed as spatial and temporal distances, relegating the latter to the periphery and to a perpetual state of arrested development.15 By polarizing Ankara and Istanbul, and mapping their differences in terms of an insurmountable chasm in time and space, Turkey’s leaders now appeared to have appropriated the same rhetoric. This was tantamount to disavowing their own social, cultural, and, at times, political loyalties and engaging in an oppositional relationship with the very people they sought to liberate. It was also uncannily similar to the relationship between the colonizer and the colonized they so overtly denounced. In other words, propelled by a genuine desire to claim a more favorable place for Turkey in a world that was ostensibly ordered and dominated by Western interests, rather than challenging the divide between West and the rest the nationalists found themselves co-opting it.

Explicating this apparent paradox, Partha Chatterjee points at the parallels between the tenets and workings of imperialism and nationalist thought in non-Western societies and suggests that, indeed, nationalism perpetuates the legacies of both Orientalism and Eurocentrism.16 Despite such fundamental similarities, however, as Chatterjee also recognizes, non-Western nationalist discourses are not simple localized replications of their more dominant Orientalist counterparts. Non-Western nationalists are often painfully aware of their tenuous position as “Easterners” in the West, and “Westerners” in the East, but never quite at home. This in-between place at the interstices of their dual and conflicted identities is precisely the platform whence they have to embark on a cautiously calculated yet volatile discourse, simultaneously reaffirming and refuting the epistemic and moral dominance of the West. In the process, they have to be and are very selective about what to adopt from the West and their choices are inescapably informed by the exigencies of their local political contexts. At the same time, from a historian’s perspective, tracing their wobbles and swivels can be quite illuminating.

The obvious inconsistencies it engendered notwithstanding, the rationale for the polarizing rhetoric used to justify the move to Ankara snaps into focus when evaluated against the tense background of political and practical anxieties the nationalist leadership felt about the form of government and the seat of power in Turkey. In the first place, they had significant security concerns. Turkey’s ability to monitor and protect the Turkish Straits had been curtailed by the Lausanne Treaty, which stipulated this to be a demilitarized zone overseen by an international commission. With virtually no control over the flow of maritime traffic across...