eBook - ePub

Democratic Brazil Divided

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Democratic Brazil Divided

About this book

March 2015 should have been a time of celebration for Brazil, as it marked thirty years of democracy, a newfound global prominence, over a decade of rising economic prosperity, and stable party politics under the rule of the widely admired PT (Workers' Party). Instead, the country descended into protest, economic crisis, impeachment, and deep political division. Democratic Brazil Divided offers a comprehensive and nuanced portrayal of long-standing problems that contributed to the emergence of crisis and offers insights into the ways Brazilian democracy has performed well, despite the explosion of crisis. The volume, the third in a series from editors Kingstone and Power, brings together noted scholars to assess the state of Brazilian democracy through analysis of key processes and themes. These include party politics, corruption, the new "middle classes," human rights, economic policymaking, the origins of protest, education and accountability, and social and environmental policy. Overall, the essays argue that democratic politics in Brazil form a complex mosaic where improvements stand alongside stagnation and regression.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

THE DEMOCRATIC CONTEXT

1

The PT in Power, 2003–2016

IN DEMOCRATIC BRAZIL: Actors, Institutions, and Processes (2000), William Nylen analyzed the role played by the Workers’ Party (Partido dos Trabalhadores; PT) in the consolidation of democracy in Brazil. According to Nylen, the PT helped strengthen Brazilian democracy in three ways: first, by conducting itself as a loyal opposition that acted within democratic limits; second, by questioning the social and economic inequalities that existed in Brazil and proposing new, inclusionary public policies within the framework of a democratic regime; and third, by providing political activists with a nonviolent channel in which to challenge the existing political order (2000, 126–27). By 2000, in the wake of Luiz Inácio (Lula) da Silva’s defeat in the presidential elections of 1989, 1994, and 1998, the PT had consolidated itself as the most important opposition party in Brazil. Two years later, Lula and the PT won the presidency for the first time and began the longest spell of single-party control over the Brazilian federal executive since the end of the authoritarian regime. However, after three complete terms, and the reelection of president Dilma Rousseff in 2014, the party faced its biggest political and institutional crisis. In 2016, after losing the party’s support in the Congress and amid a strong economic recession, Dilma Rousseff was involved in the second impeachment process in the country since the end of the authoritarian regime.

What did twelve years in Brazil’s Planalto Palace mean for the PT and for democracy in Brazil? What did this period represent for the Brazilian party system and for political competition in Brazil? What were the principal changes that took place within the PT during that period? A decade of PT presidency brought improvements in the quality of democracy in Brazil, although certain obstacles remain to the cementing of the regime’s legitimacy among Brazilian citizens, as the economic and political crises in 2015–2016 clearly show.

There have been clear changes in the Brazilian party system between 2003 and 2016. While the Brazilian party system has stabilized over the past decade, it is still weakened because support for parties is not firmly entrenched in the electorate. Important transformations that occurred under the PT administrations, such as the significant reduction in national income inequality and the positive impact of poverty reduction programs, have proved to be important sources of political support during most of the PT’s period in power, and PT governance has impacted on the perceptions Brazilians hold of democracy more broadly. The PT has also undergone transformations during its twelve years in power. Its organizational structure and programmatic ideology have evolved, and the party has experienced significant growth in its membership base and proved capable of maintaining a network of fruitful relationships between its leadership and social movements. However, it did not build mechanisms to prevent its leaders from involvement in corruption scandals connected to electoral campaigns. With regard to its programmatic scope, the PT opted to respond strategically to the dynamic of alliances fostered by coalitional presidentialism, even though these decisions resulted in political defections and a shift to the right. Organizational changes have been more gradual than programmatic ones, creating a source of tension inside the party during its period in power.

The Party System, 2003–2016

The Brazilian political system combines presidentialism, federalism, and a hybrid-norm electoral system that produces majoritarian and consociational arrangements in high magnitude districts. The resulting high number of actors contributes to a highly fragmented party system at the national level, allowing presidential elections to dictate the logic of party arrangements and political strategies (Limongi and Cortez 2010; Meneguello 2010). Furthermore, because the system relies on direct elections at the federal, state, and municipal levels, voters have the power to shape both executive and legislative electoral outcomes and can therefore dictate the character of the ultimate governing coalition.

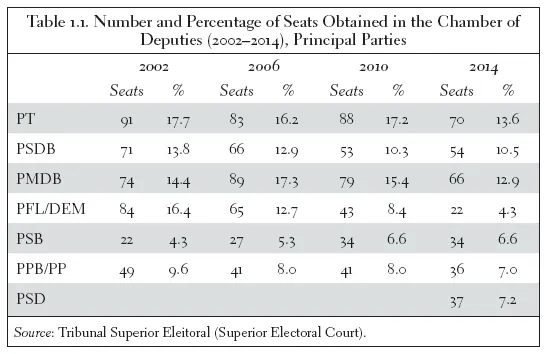

What were the effects of twelve years of PT power on the party system? How did this period alter the patterns of political competition observed in Brazil? One way to answer these questions is to analyze the electoral performance of the PT between 2003 and 2014. In the three general elections in which the party participated while holding the presidency, the PT’s performance at the national level was marked by stability. In the presidential elections of 2006, 2010, and 2014, Lula and then Dilma received, in the first round of votes, 48.6 percent, 46.9 percent, and 41.6 percent of the vote, respectively. As a result, both candidates had to compete in a second round of voting against Geraldo Alckmin (2006), José Serra (2010), and Aécio Neves (2014), all members of the Party of Brazilian Social Democracy (Partido da Social Democracia Brasileira; PSDB). In elections for the Chamber of Deputies during the same period, the PT received more votes than any other party in all elections but did not achieve significant growth and in fact declined relative to its performance in 2002. In that election the PT had received 18.4 percent of the vote and won 17.7 percent of seats in the Chamber. Four years later, the party obtained 15 percent of the vote and 16.2 percent of seats. In 2010, the percentages were similar: 16.8 percent of the vote and 17.2 percent of seats. In 2014, the party received 13.9 percent of the votes and obtained 13.6 percent of the seats (table 1.1), reflecting the increased level of party fragmentation in the lower house.

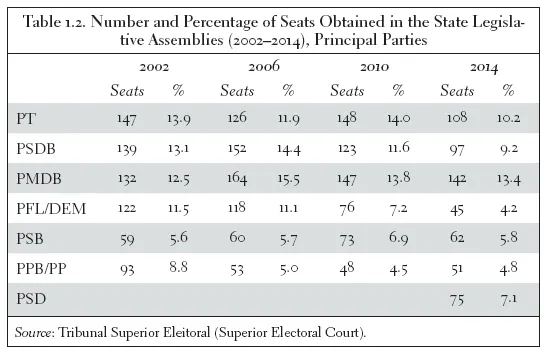

At the state level the PT’s results were equally modest. In 2002 the PT held three of the country’s twenty-seven governorships. In 2006, 2010, and 2014 that number rose to five. In the state legislative assemblies, the party held 147 assembly seats (13.9 percent of the total) in 2002; that figure fell to 126 seats (11.9 percent) in 2006, rose to 148 (14 percent) in 2010, and dropped back to 108 (10.2 percent) in 2014 (see table 1.2). At the municipal level, the party experienced substantial growth in the 2004 elections, achieving a 48 percent increase in the number of municipal council seats (vereadores) held and a 120 percent increase in the number of mayoralties (prefeituras) held, relative to the year 2000. In the elections of 2008 and 2012, the PT continued to gain seats, but at a slower rate. By the end of the period in question, after twelve years occupying the presidency, the PT held only 8.5 percent of municipal council seats and 11.6 percent of Brazil’s more than 5,500 mayoralties.

Data on voting patterns in presidential and legislative elections shows the consolidation of two distinct competitive dynamics in the Brazilian political system. On the one hand, presidential elections have essentially become two-party contests. Since 1994 the PT and the PSDB have been the only parties whose candidates have garnered more than 25 percent of the presidential vote. The effective number of parties in the presidential elections of 2006, 2010, and 2014 were 2.4, 2.7, and 3.0, respectively. These numbers are consistent with the data from 1994 (2.7), 1998 (2.5), and 2002 (3.2). On the other hand, electoral competition for the Chamber of Deputies is quite open. In 2010 and 2014 only three parties (the PT, the PSDB, and the Brazilian Democratic Movement Party [Partido do Movimento Democrático Brasileiro; PMDB]) obtained between 10 percent and 20 percent of votes for the legislature. These numbers are similar to data from elections in 1990, 1994, 1998, 2002, and 2006. The result has been a Chamber of Deputies with a high—and increasing—level of fragmentation. The effective number of parties in the Chamber of Deputies was 8.5 in 2003, 9.3 in 2007, 10.4 in 2011, and 13.2 in 2015—numbers that are broadly consistent with the data from 1991 (8.7), 1995 (8.2), and 1999 (7.1).

The restriction of viable presidential candidacies to the PT and PSDB between 1994 and 2014 reflects the Brazilian electorate’s support for parties that offered strong leadership based on different visions for the country’s development. The PT and the PSDB each led a partisan block with a distinct program. While the PSDB served as an organizing pole for Brazil’s center-right parties, the PT played a similar role for the center-left. That dynamic has also played out at the state level, demonstrating the importance of presidential elections in shaping partisan alliances at all levels of the Brazilian political system (Limongi and Cortez 2010). The diversity of parties found in the Chamber of Deputies results from the Brazilian electoral system’s combination of open lists with proportional representation in high magnitude districts. Worthy of note is the fact that stability in the effective number of parties competing for legislative seats is accompanied by consistency in the principal party actors present in the Chamber. Electoral volatility indexes, which measure the stability of voter behavior in successive elections, are thus another indicator of the consolidation of stable party dynamics. Data on volatility is available for congressional elections from 1990 onward. Volatility in the most recent elections was measured at 15.3 (1998), 14.9 (2002), 10.4 (2006), 11.2 (2010), and 17.6 (2014), a figure close to the average found in advanced industrial democracies (Mainwaring, Power, and Bizzarro, forthcoming).

Many scholars have observed that the Brazilian party system between 2003 and 2014 exhibited a growing stability (Limongi and Cortez 2010; Zucco 2011; Peres, Ricci, and Rennó 2011; Meneguello 2011; Braga, Ribeiro, and Amaral 2016). The routinization of democratic life, a general adherence to the rules of the game, the permanence of the same party actors and the emergence of a two-party cleavage in presidential contests all added predictability to electoral outcomes and conferred stability on the system more broadly. This is a positive development and indicates that the Brazilian party system is capable of processing demands and institutionalizing existing conflicts in Brazilian society. Furthermore, greater stability brings a greater capacity to coordinate political and electoral strategy within parties. These factors contribute to the stability of the democratic regime and help legitimize it.

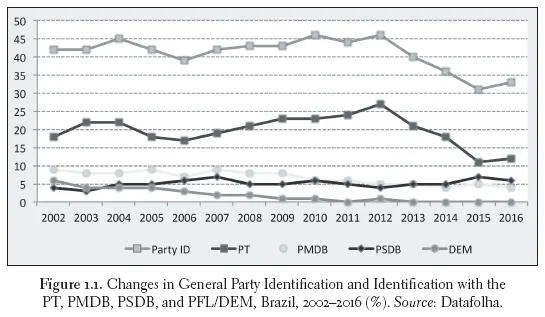

However, increased stability has not translated into the firm entrenchment of parties within the electorate, as the data on party identification and loyalty indicates. With the exception of the PT, all Brazilian parties have had low levels of identification (figure 1.1). The PT, in addition to being an anchoring pole in the system of political alliances, is the only party that has garnered significant mass support in Brazil. The party, however, has been hit by the general crisis of representation that affected the whole party system between 2013 and 2016. Identification with the PT has dropped from 27 percent in 2012 to 12 percent in 2016. For the PT, this crisis was more dramatic: the party lost one element of the ethical politics brand it had strived to build in the 1980s and 1990s, as its leaders were embroiled in corruption scandals. Furthermore, the party was unable to respond effectively to the economic crisis of 2015–2016.

The PT Government

The PT era ended in a very unpredictable way, combining economic and political crises, a polarized society, and the impeachment trial of president Dilma Rousseff. The PT administration, however, oversaw a number of well-known successes, especially between 2003 and 2013 when the PT government was responsible for the implementation of internationally lauded cash transfer programs, the expansion of employment, and increases in wages. Although to some extent improvements in the economy under the PT were a result of Brazil being insulated from the effects of the international financial crisis of 2008–2009, it is worth emphasizing that, by 2010, the PT had managed to significantly expand consumption in Brazil, including among low-income sectors of the population, who benefited from policies that brought higher wages and expanded the availability of credit. The emergence of what became known as the “new middle class”—the nova classe C—led to a rise in family income and consumption in previously marginalized sectors of the population. However, the economic success of the first decade in office came to an end in early 2014. The collapse of commodity prices, the economic slowdown in China, the rise in inflation, and a series of poor decisions regarding fiscal and investment policies drove the country into economic recession, with its GDP decreasing by 4.0 percent in 2015, and unemployment rising to 9.0 percent—the worst figure since 2009.

The PT also oversaw political successes resulting from programmatic deliberations. With regard to poverty reduction, the success of the PT government is indisputable: the expansion of Bolsa Família, which increased from 3.6 million beneficiaries in 2003 to 16.7 million beneficiary families in 2010, meant that a quarter of the Brazilian population received transfers from the program (Soares and Sátyro 2010).

While the first PT government (2003–2006) presided over only modest improvements in indicators of economic growth, it did oversee an important increase in the equality of income distribution. This resulted both from factors associated with the labor market, such as changes in the supply and demand of labor and real increases in the minimum wage, and from the improvement of social safety nets, particularly with the expansion of cash transfer programs such as the Bolsa Família program (Sergei Soares 2006). Social programs played a role in the substantial reduction in poverty that took place in Brazil between 2003 and 2006, when there was a 27.7 percent drop in the proportion of Brazilians living below the poverty line. By 2005 the poverty rate had fallen to 22.8 percent, and by 2006 it reached 19.3 percent. In addition, after 2004 there was a 6.6 percent increase in average income, which primarily benefited the poorest 50 percent of Brazilians, who experienced an average income increase of 8.6 percent. For middle and upper income brackets, the increases were 5.7 percent and 6.9 percent, respectively (Neri 2007).

Under Lula’s second government (2007–2010), Brazil not only was the country least affected by the global financial crisis of 2008–2009 but also experienced significant reductions in its poverty rates. Relative to 2003, the percentage of Brazilians living below the poverty line decreased by an impressive 50.3 percent. Moreover, a 20 percent increase in average income between 2004 and 2009 made new levels of consumption possible and helped incorporate previously marginalized segments of the population into the market system; particularly notable is the fact that over 50 percent of the Brazilian population benefited from popular credit programs (Neri 2010, 2011b).

The reductions in poverty and increases in income that took place under Lula had a significant impact on public support for the PT government. A brief analysis of fluctuations in political support during the PT’s time in power reveals certain trends in the relationship between the democratic regime and Brazilian society. The success of the PT government in defining an agenda centered on implementing wide-ranging social programs and a policy of prioritizing improvements in employment and income generated significant mass support from the beginning of the party’s first presidential term.

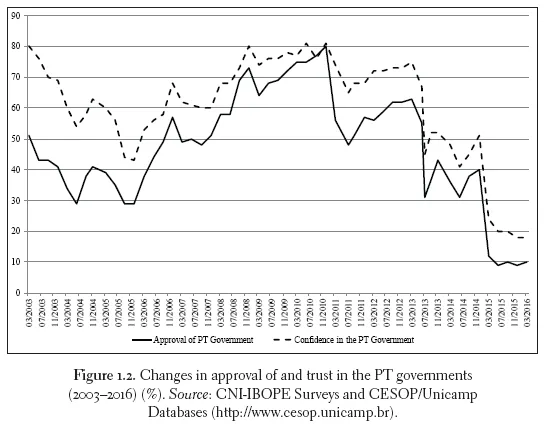

Public opinion surveys show that improvements in economic and social indicators correspond with increases in public approval of and trust in the government. During the first two PT governments, public trust in the government was consistently high, particularly during Lula’s second term. Notably, trust remained high even during a period of political crisis in 2005 that enveloped the PT in accusations of corruption, which reached prominent government figures. By March 2006 public trust had been fully restored, and by the end of Lula’s second term in 2010, the government had the trust of 81 percent of the population.

Public approval of the government followed a similar pattern. During both of Lula’s presidential terms, but particularly during his second, approval ratings were high. Although the government’s approval ratings dropped as a result of PT corruption scandals, by the end of Lula’s second term the party had the highest approval rating on record (80 percent of the population). The political capital that accrued from such high levels of public approval helped ensure a third PT term. At the beginning of Dilma’s first term, both approval and trust remained high. In March 2013, 75 percent of Brazilians expressed trust in her government and over 60 percent gave her a positive approval rating. It was not until after June 2013—when a series of popular demonstrations demanding better public services and protesting against corruption took to the streets in many cities throughout the country—that her approval rating began to fall, stabilizing at around 40 percent. In 2015, with the deepening of the economic crisis, income reduction, the increase of unemployment, and the development of the investigations against corruption under the Lava Jato operation, the figures plummeted. In March 2016, only 10 percent approved of the PT government, and only 18 percent trusted it (figure 1.2).

It is important to remember that economic indicators have played an important role in determining levels of political support since the beginning of the post-1985 democratic period in Brazil. Studies on the determining factors of voting patterns in presidential elections suggest that since 1994, when the Plano Real changed voter expectations of government performance, a new pattern has emerged wherein a candidate’s past performance and voter expectations about the candidate’s future accomplishments constitute the strategic content of the vote. This strategic decision is oriented around the voter’s individual interests and expectations of well-being and consumption—the so-called economic vote (Meneguello 1995; Balbachevsky and Holzhacker 2004). Under Fernando Henrique Cardoso’s government (1995–2002), the state of the economy and levels of government approval were crucial determinants of election outcomes. But since the PT’s presidential victory in 2003, partisan identification and political loyalty to particular candidates have also factored into voting decisions. The influence of partisan loyalty was especially clear in 2006, when national surveys taken before the beginning of the presidential campaigns showed significant loyalty to Lula across elections: 49.9 percent of voters interviewed believed that Lula deserved to be reelected in 2006, and of those, 64.7 percent had voted for Lula in 2002 (Desconfiança Survey 2006).

Survey data collected in 2006 and 2010 also suggests that political loyalty was a crucial factor in determining voting decisions for PT candidates. A survey conducted after the 2006 election found that 85 percent of voters who voted for Lula in the first round of voting in 2006 also voted for him in the first round in 2002. Furthermore, 80 percent of voters who chose Lula in the second round in 2006 also voted for him in the second round in 2002, and 92.4 percent of those who voted for Lula in the first round in 2006 also voted for him in the second round that year (ESEB Survey 2006).

Dilma Rouseff’s presidential candidacy also benefited from high levels of political adhesion in PT voters. Although the extent to which popularity can be transferred from one candidate to another is clearly limited, the mass political support acquired by President Lula helped drive, in part, the continuation of high levels of partisan identification for other PT candidates. Survey data from 2010 shows a remarkable persistence in voter identification across candidates and elections: 62 percent of those who voted ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Acronyms

- Introduction. A Fourth Decade of Brazilian Democracy: Achievements, Challenges, and Polarization

- Part I. The Democratic Context

- Part II. Policy Innovation and State Capacity in a Maturing Democracy

- Part III. Politics from the Bottom Up

- Part IV. Strategies of Global Projection

- Notes

- References

- Contributors

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Democratic Brazil Divided by Peter Kingstone, Timothy J. Power, Peter Kingstone,Timothy J. Power,Peter R. Kingstone in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Global Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.