eBook - ePub

Victorian Medicine and Popular Culture

This is a test

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Victorian Medicine and Popular Culture

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This collection of essays explores the rise of scientific medicine and its impact on Victorian popular culture. Chapters include an examination of Charles Dickens's involvement with hospital funding, concerns over milk purity and the theatrical portrayal of drug addiction, plus a whole section devoted to the representation of medicine in crime fiction. This is an interdisciplinary study involving public health, cultural studies, the history of medicine, literature and the theatre, providing new insights into Victorian culture and society.

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access Victorian Medicine and Popular Culture by Louise Penner, Tabitha Sparks, Louise Penner,Tabitha Sparks in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Science General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

‘Dr Locock and his Quack’: Professionalizing Medicine, Textualizing Identity in the 1840s

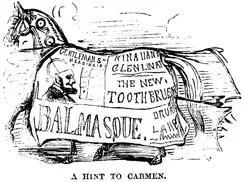

Figure 1.1:‘A Hint to Cabmen’, Punch, 14 January 1847, p. 31, AP101.P8, E. S. Bird Library, Syracuse University.

In early 1846, while Londoners debated a proposal to line the interiors of omnibuses with advertisements, a contributor to Punch declared: ‘Advertising is certainly the great vehicle for the age’. The writer’s pun registers both awareness that modes of marketing commodities in Victorian England had been transformed and anxiety about the onset of a culture of advertising stimulated by a variety of factors, including the growth of the middle class, the increase in literacy and the expansion of consumer goods. Indeed, the contributor’s greatest concern was the distress commuters would experience, while making their way across the metropolis, from long-term exposure to so-called quack medicine advertisements (See Fig. 1.1).2Among the few extant studies of Victorian advertising, most agree that in this period the marketing of goods took on an identifiably modern appearance. Thus, contemporary cultural historians have often approached Victorian advertisements much as they would in our own image-saturated culture, noting how advertisements either generated consumer desires, by the same productive processes that also attempted to satiate them, or participated in normalizing social identities.3 Reading medical advertisements as historical documents that provide insight into nineteenth-century British culture, several scholars have focused on the ways advertisements preyed on public fears about the sources and the spread of disease.4 In mid-nineteenth-century England, the prevalence of consumption and other wasting diseases, the lack of a shared consensus among medical practitioners about how to properly treat illness and the emergence of a culture of advertising engendered particularly auspicious conditions for profitable charlatanism.

These arguments about the cultural work advertisements performed in the Victorian period are compelling. Yet to read medical advertisements solely in terms of how they manipulated public health fears is to reduce their possible meanings to the claims of the advertisements themselves. In what follows, I will analyse the controversy that evolved in the pages of The Lancet, founded by Thomas Wakley in 1823 and now Britain’s leading medical journal, about a series of print advertisements for Dr Locock’s Pulmonic Wafers.5 Beginning in the 1840s, various advertisements for the wafers began appearing regularly in newspapers, magazines and serialized novels. These ads made a variety of claims. Some stressed the wafers’ soothing ability to alleviate sore and strained throats in minutes. Others touted, during a period when ‘fevers’ were prevalent, the wafers’ curative or preventive powers. Indeed, ads for the product promised both to cut in half the number of deaths in London from ‘diseases of the chest’ and to offer relief from ‘Asthma and Consumption, and all Disorders of the Breath and Lungs’. But the product’s appeal was, perhaps, chiefly dependent on its use of the name Locock.

This was a deliberate evocation of Sir Charles Locock, a prominent obstetric physician in London who was appointed Queen Victoria’s first physician accoucheur in 1840. The suggestion that so eminent a physician had conceived of the wafers, though he did not, was enough to guarantee the product’s success for several decades. Whereas an older generation of doctors either had patented their own nostrums for sale or silently acquiesced – in Locock’s case out of a sense of futility – to the use of their names, The Lancet editorials argued that the easily appropriable nature of identity was one of the biggest obstacles to reforming medical practice into an organized profession. Wakley, therefore, launched a campaign in the pages of his journal against quack medicine advertisements and urged practitioners not to endorse medicinal products. Motivated by financial gain, doctors had long lent their names to products, often of dubious quality, and in so doing, Wakley argued, lowered the esteem of all those who practiced medicine.6 Yet even if he were successful in convincing his older colleagues to discontinue endorsements of medicines and the new generation of practitioners not to take up the custom, Wakley recognized that in a changing print culture the problem of forgery remained. Hence, he advocated for stabilizing professional identity through medical certification and legal redress. This episode demonstrates that Victorian print advertisements need to be read, not only for their interpellative functions – or how they participated in refashioning subjectivity according to an ideology of consumption – but also for the ways in which, at least some raised concerns among the emergent professional classes about alienable identity.7

Throughout much of the nineteenth century, one’s professional status as a physician, surgeon or apothecary was determined less by the examining bodies, to which one might submit for certification, than by patronage. ‘The aspirant to a status higher than that of surgeon-apothecary (the prototypic general practitioner)’, Russell C. Maulitz points out, ‘knew full well that advancement depended upon a favoured position within London’s medical plutocracy’.8 Thomas Wakley founded The Lancet as a vehicle for highlighting corruption and nepotism among medical practitioners.9 An editorial, almost certainly written by Wakley himself, prefacing the first issue insisted that ‘we shall be assailed by much interested opinion’, but expressed a hope that ‘mystery and concealment will no longer be encouraged’. Only by acquiring real and disinterested knowledge of one’s subject could the dedicated practitioner help to break up the oligarchic nature of the medical profession. ‘[A] little reflection and application’ on the subject of medicine, the editorial states, ‘would furnish him with a test by which he could detect and expose the impositions of ignorant practitioners’.10 Therefore, as Ronald Cassell explains, Wakley saw The Lancet as a crucial means for challenging the ‘privileged superiority’ among ‘the well-connected physicians and surgeons who dominated the lucrative hospital teaching positions and the councils of the Royal Colleges in London, Edinburgh, and Dublin’.11 He pressed the Royal College of Physicians and the Royal College of Surgeons to implement a system of qualification for their members, such as a program of certification, in order to curtail the rampant nepotism at both institutions.

As part of Wakley’s campaign for reform, he focused the attention of The Lancet’s readers on the prevalence of print advertisements for various medicinal products: pills, powders, lotions, lozenges, ointments, drops and wafers, among others.12 Most of these were dubious at best. The Apothecaries Act of 1815 had attempted to regulate the prescription and sale of drugs in England and Wales by mandating that a Court of Examiners be established to certify and license all apothecaries. But this act notwithstanding, and unlike other European countries, including Germany, which had granted a strong role for the state through the medical police, there was remarkably little tolerance in England for state intervention into health-care practice.13 Even with the passage of the act, one could simply sidestep the law by not proclaiming oneself to be an apothecary and arranging for one’s products to be sold by chemists, grocers and booksellers. Additionally, not all products were manufactured by quacks. Some of the best-known medical professionals of the time either endorsed products or sold them under their names.

Nationwide advertising of medicine in Britain began in the eighteenth century alongside the beginning of the standardized, brand-name commodity and the improvement in systems of goods distribution. Medical practitioners were eager to take advantage of the advances in pharmacology by branding their own products for sale in outlets across the nation and thus expanding their client base well beyond the metropolis. A large percentage of these advertisements appeared in working-class and religious periodicals, reaching a much wider audience than either the urban wall poster or the handbill, which were the primary methods of advertising by street vendors in the eighteenth century. When rules against advertisements in middle-class periodicals began to relax in the first half of the nineteenth century, profiteering doctors, as well as those with no medical background, took advantage of the expanded base of potential customers. In a practice that originated in the eighteenth century and continued into the Victorian period, as Roy Porter points out, ‘[p]rinters acted as distributors of medicines, typically selling them from their offices or bookshops (where they sold the medical books advertised in their papers) – and even delivering them, through their agents and newsboys, with the newspapers themselves’, and ‘nostrum advertising directly supplemented the editor’s revenue’; by the same token, purveyors benefited from having wider, and increasingly national, distribution channels.14 Because England at the time had neither a national product regulation agency nor safety standards to which products had to adhere, the quack-medicine trade was well positioned to exploit these expanded opportunities.

A system of certification might help to eliminate nepotism and corruption within the Royal Colleges of Physicians and Surgeons, but it would not prevent the problem from persisting. Wakley placed advertisements at the centre of his campaign for reform because he believed that the profession would never gain the kind of legitimacy in the eyes of the public that he imagined for it so long as the line between medicine and quackery was blurred. Through The Lancet, he called attention to the different ways doctors abetted fraudulent medicine. ‘Medical men’, an extended editorial in the issue of 28 February 1846 proclaimed, ‘have so frequently given the sanction of their names to preparations of doubtful origin, that society is confused’.15 By licensing their names to products, doctors stood to accrue significant financial benefits or increased celebrity. ‘There is a very prevalent feeling among the profession, that physicians and surgeons sometimes give testimonials with a desire to see their names paraded and advertised as professional authorities’, he insisted. Some doctors, for an extra guinea, would even bring unlicensed druggists with them on patient visits.16 As a consequence of such malfeasance, the journal argued, the public had great difficulty in determining the difference between legitimate doctors and their pharmacology and exploitative quacks and their nostrums.

Because an individual had no firm basis for distinguishing between legitimate and illegitimate forms of treatment, Wakley contended, one might end up taking a toxic remedy marketed as a cure. To emphasize the consequences of professional malfeasance, The Lancet featured family testimonials and coroner’s reports that directly connected various quack medicines, or dubious courses of treatment, such as the ‘water-cure’, with patient deaths. Wakley and his contributors tended to single out the most egregious cases in order to contrast the imagined gentility of professional medicine with the commercialization of quackery.17 Thus: ‘An inquest was held at Cardiff, before R. L. Reece, Esq., coroner, on view of the body of Mr. John Nisbett’, one story read. ‘I am of the opinion that the late John Nisbett died of pulmonary apoplexy … [and] that his death was accelerated by the continued use of large doses of drastic purgative medicines’.18 James Morison, a retired merchant who fiercely opposed ‘orthodox’ medicine, marketed his ‘Universal Vegetable Pills’ – a laxative variously made from aloes, jalap, gamboges, colocynth, cream of tartar, myrrh and rhubarb – as an affordable way for patients to manage their own illnesses. He believed that ‘all maladies arise from impurity of the blood, though they may show themselves under various forms’.19 Hence, the universal nature of the pill – which was an effective combatant, he claimed, against fevers, scarlatina, smallpox, consumption and senility.

Wakley had fought against Morison’s quackery since the mid-1830s, when an editorial in The Lancet declared that the latter was guilty of ‘fraud and extortion’ and his pills nothing more than ‘active poison’ implicated directly or indirectly in a number of deaths.20 As part of its efforts against quack medicine, The Lancet provided a national forum for health-care providers to share information with other medical professionals and interested lay people about the effects of illegitimate nostrums: reports ranged from a summary of an inquest into the death of three-year-old Caroline Julia Hurst of Buckle Street, Whitechapel, who died from ‘effusion on the brain, which may have resulted from disease, or from the effects of the drops’ of ‘strongly narcotic’ patent medicine taken for ‘hooping-cough’, to the account of a butcher, previously convicted and jailed for practicing ‘surgery’ on a ‘patient’, who prescribed mistletoe tea to a young man suffering from and ultimately succumbing to chorea.21 Despite numerous reports of patient deaths, however, the quack-medicine trade was highly lucrative; Morison sold over 1,100,000 boxes annually.22

What made patent medicines so popular? One reason is that, until medical practitioners reached a consensus later in the century on the causal relationship between unsanitary conditions an...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- CONTENTS

- Acknowledgements

- List of Contributors

- List of Figures

- Introduction

- 1 ‘Dr Locock and his Quack’: Professionalizing Medicine, Textualizing Identity in the 1840s

- 2 Dickens, Metropolitan Philanthropy and the London Hospitals

- 3 Cleanliness and Medicinal Cheer: Harriet Martineau, the ‘People of Bleaburn’ and the Sanitary Work of Household Words

- 4 Lacteal Crises: Debates over Milk Purity in Victorian Britain

- 5 ‘The Chemistry and Botany of the Kitchen’: Scientific and Domestic Attempts to Prevent Food Adulteration

- 6 Medical Bluebeards: The Domestic Threat of the Poisoning Doctor in the Popular Fiction of Ellen Wood

- 7 Male Hysteria, Sexual Inversion and the Sensational Hero in Wilkie Collins’s Armadale

- 8 Ungentlemanly Habits: The Dramaturgy of Drug Addiction in Fin-de-Siècle Theatrical Adaptations of the Sherlock Holmes Stories and The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr Hyde

- 9 From Vivisection to Gender Reassignment: Imagining the Feminine in The Island of Doctor Moreau

- 10 Illness as Metaphor in the Victorian Novel: Reading Popular Fiction against Medical History

- Notes

- Index