![]()

FOUR

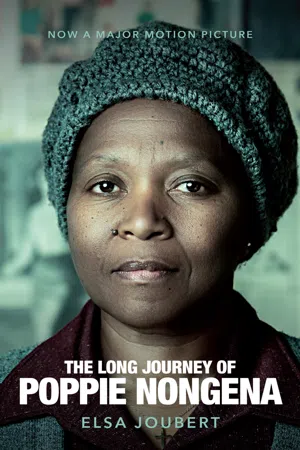

Poppie’s pass

![]()

32

After the strike Poppie went to the clinic to ask if the bed in the hospital was still free. The doctor said: Yes, Stone must come.

But Stone was again unwilling and accused Poppie: You want to get me out of the house.

She took him to the clinic and went along in the bus to the hospital in Westlake, but he wouldn’t speak a word to her. She walked with him up to his bed in the ward and helped him undress, but still he didn’t speak a word to her.

You can come on Sunday afternoons to see him, the nurse said.

A month after the strike, Mrs Graham went back to England and Poppie lost her char work. To get her pass fixed before taking on a new job she went to the new office in Nyanga, two old brick buildings where white people had formerly lived, now fixed up as an office.

They gave me an extension for six months, but after six months when I went back-I didn’t have a job yet because with a sick husband and small children at home it was too difficult-now Mr Strydom looked at my pass and he said: You don’t qualify for the Cape, you must go away to the Ciskei.

It was the first time that I had heard such words. I thought: They brought me here to the Cape, they wouldn’t say such a thing now. I didn’t think it so serious, I thought: Perhaps it is just his way of speaking.

Mama, said Poppie that night to her ma – but she made it sound like a joke, because she didn’t believe it – mama, they want to send me to Kaffirland.

Mama didn’t take it seriously either. But still she said: Then you must see that you get a job. If you’ve got a job, they can’t send you away. Katie must leave school and look after your children.

Poppie wouldn’t have it that Katie should leave school. I’ll manage by myself, she said.

She went to work for Mrs Scobie at Rondebosch for eight pounds a month.

When the clinic heard that I had a job, they took away the disability grant because a person working doesn’t qualify for the grant. So the job meant only four pounds extra to what I had been having, but working helped me to change my pass.

The work at Mrs Scobie’s was inconvenient. She worked sleep-out, from eight in the morning till five in the afternoon, she cooked in the afternoons and put the food in the warming oven for the four adults who were at work, the parents and two children. She worked from Sunday right through the week. Sundays Mrs Scobie’s other married daughter and husband and two grandchildren came to dinner, they ate till two o’clock, then she didn’t leave the kitchen till after three.

Sunday was the only day I could go to Westlake to see my husband, says Poppie. It’s beyond Retreat, past Pollsmoor, and on Sundays the buses were few. When I got there, it was too late, past visiting time. As I came down the road I’d see my husband standing inside the gate, waiting for me. But the gates were locked and we’d have to stand talking through the bars. That’s where he started getting jealous. Where were you? he asked. With whom have you been carrying on? What are you doing all the time, while I’m stuck away here?

Sometimes he started weeping. He became thin and weak.

It was also very difficult because I had no one to look after the children. Mosie and Johnnie Drop-Eye stayed with me, and buti Plank off and on, but they were at work. When the weather was bad, buti Plank came home from the boats. When he wasn’t drunk he was as gentle as a woman with the children.

But other days I had to leave them in the house. The little boy, Bonsile, was in Sub A but the others did not go to school yet. When I left them there, I hid the matches – because children like playing with matches – and locked them in the house. I’d say to the neighbours, I’m going to my job, keep an eye on them. I kept the boy from school and he looked after the other children well. He was seven, the girl five years and the youngest two. Later on they got used to staying alone, because I told them, I don’t want other people’s children in my house when I’m at work, because I lose my stuff, the children carry things away. Now they are content, and I leave them bread and cold tea, everything cold, they must eat it cold.

The hardest thing for me was when the children got sick. You leave the children well in the mornings and when you come back in the afternoon, you find one is ill with a cold, or earache, or feverish. By then the sun has already set, but you’ve got to leave the other two again and walk with the sick one to hospital, that was the hardest. And the houses we lived in, they could take fire so easily, they were only pondokkies of corrugated iron and wood. At work, I used to think perhaps: Has my house burnt down? And have the children run out in the street? Sometimes when you got to Claremont station, you’d hear them talking of a child run over by a car, then you’d get a fright that makes water of your body, and you’d be in a hurry to get home to see if the children were all safe.

The boy was a quiet child, like his father, but he was a good child, fond of his little sisters, not fond of fighting or naughty like. The little girl was four or five years old when she asked me in Xhosa-the children in the location didn’t learn much Afrikaans – she asked me: Mama, who does mama love, me or Thandi. Then I got a fright, because I didn’t think a child of mine would ask such a thing. I didn’t know what she had seen, Thandi was about two, they were close together in age. Then I said: No, but I love both of you. Then she said: Oh, I thought mama loved Thandi more.

It gave me a fright, because she was too young to ask such a thing. What made her ask it, I don’t know. I was always tired and worried when I got home, perhaps I didn’t always treat the children right.

![]()

33

Your buti keeps talking about Muis, said mama. Muis was half-coloured, half-Xhosa. After the strike it seemed she’d dropped him. Now they’d made up again. Mama didn’t often come to see Poppie, she worked sleep-in and, when she was off,.had to see to her own house and children.

She’s not the wife for buti Hoedjie, said Poppie.

Mama sat at the table on a straight-backed chair. She rubbed her hand over the table, the table which she had bought Poppie in Lamberts Bay. She’s a hard worker, said mama.

Forget the hard work, mama, I don’t like her ways. I had a good look at her when she and another woman came here to see Mamdungwana. She works for a month or a week, they say she can’t keep a job.

Perhaps she’ll help your buti, said mama.

But who are her people, from where does she come? We only know she hasn’t got no people, and she grew up in a reformatory at George.

But mama’s heart was for Muis. I can’t help it, but I already love her. It’s surely because of her hardworkingness.

Poppie wouldn’t go to the wedding. Buti Plank was on the boats at sea, but Mosie went. Poppie wasn’t pleased that he went. That thin girl with the legs like sticks, I can’t stand her, she told him.

Mosie thought: My little sister is jealous that her buti is leaving her for another woman. Even if he gives her so much trouble.

They were married in Rylands, in the house of the minister of Muis’s church.

It’s not the place for our people that, said Poppie, the Indians and coloureds live there in brick houses, but the Xhosas must live in pondokkies.

The only comfort for Poppie was that buti Hoedjie didn’t need to pay lobola for such a cast-off orphan child.

Mama gave them a party and Hoedjie and Muis roomed with her. But after two weeks she left mama to stay at another woman’s house. Then she started drinking with Hoedjie.

And where now is the woman that’s so hardworking? Now mama can see her for what she is.

She is good to Hoedjie, mama kept on. But she’s just like kleinma Hessie was, she’s got long fingers and she can’t keep her hands off my things.

Perhaps that’s why she was sent to the reformatory, she is a thief.

Keep your mouth, Poppie, said mama. She never had no ma or brothers like you had.

Kleinma Hessie wrote: When Mosie has to go to the bush, he must come to us, he was always like our child.

Kleinma Hessie had gone back to kleinpa Ruben, who now was the ...