![]()

1

Historical and cultural background

Belfast, Beirut and Berlin: Three histories of division

Richard Sennett claims that the encounter of entirely different individuals in a city intensifies ‘the complexity of social life’.1 This holds specifically true in the case of divided cities in which the structure of the urban population is particularly complex. To understand the issues raised in the films under scrutiny, an introduction to Belfast’s, Beirut’s and Berlin’s functioning during the respective conflicts seems to be necessary. Scott A. Bollens observes that ‘city division can be physical, psychological, and/or social in character’.2 This also applies to the three cities central to this book, as all of them are characterized by what Bollens calls ‘physical markers’ and ‘invisible lines’, which in different ways are ‘behaviour-shaping and limiting’.3 While physical barriers occur in the form of walls and other territorial indicators, ‘invisible lines’ manifest themselves in the shape of psychological boundaries which prevent individuals from freely moving through a given urban space. In the case of Belfast, Beirut and Berlin, political division is the prominent theme, even if this division may also contribute to a growing social gap. Bollens further notes that polarized cities are commonly platforms for the playing out of broader epic struggles tied to religion, historic political claims, ideology and culture.4 This statement is accurate in the case of Belfast’s and Beirut’s segregation in which the interrelation between religion, culture and historical political claims plays a salient role. As to Berlin, the city’s division was generated due to the clashing of two ideological systems which were disconnected from religious belief and cultural issues. Only after Berlin’s partition did two contrasting cultures develop in the two parts of the city.

The conflicts having taken place in the three cities are of very different nature. Whereas Beirut was the scene of a civil war with warring militias confronting each other on the streets, the violent confrontations in Belfast are not to be seen as a war but as ‘an armed conflict without trenches and uniforms’,5 in which belligerent paramilitary organizations, the British army and the local police force were involved in intense political fighting. In Northern Ireland, unofficial armed groups are called ‘paramilitaries’, whereas their Lebanese counterparts are referred to as ‘militia’. Even if the aim of the groups was similar, that is the defence of a certain territory and a certain community, different terms are used to refer to them according to the geographical zone in which they occur. Berlin, on the contrary, was the centre of the Cold War, that is a conflict falling short of military action but characterized by continual political pressure and threats.

Peace lines, murals, kerbstone paintings: Belfast’s internal boundaries and borders

In the nineteenth century, Belfast became Ireland’s industrial centre with a thriving tobacco and linen industry. At this time, the city’s shipyard Harland and Wolff – the place in which the Titanic was built – was considered as the biggest in the world.6 Thanks to its flowering industry, Belfast attracted numerous Catholic and Protestant workers from all parts of the island. The influx of members of both ethno-religious communities generated a mixed population in the city.7 At the end of the 1960s, Belfast’s industry suffered a severe crisis, which affected mostly working-class Catholics as well-paid jobs were frequently monopolized by the Protestant community. Due to the tense situation, many people left the city and those who stayed on began to live in almost exclusively Catholic or Protestant areas.8 Residential segregation intensified after the outbreak of the Northern Irish conflict in 1968, which claimed almost 4,000 lives.9 The main belligerent groups represented the Irish nationalists and republicans, wishing to end the partition of Ireland, and the unionists, desiring to maintain constitutional and cultural links with the rest of the UK. Today, the city has about 300,000 inhabitants and two main ethno-religious communities, which are split almost evenly. The Protestant community is slightly bigger than its Catholic counterpart10 with 48 per cent of the overall population being Protestant and 45 per cent Catholic.11

The roots of the Northern Irish conflict lie in the Plantation of Ulster, which started in the sixteenth century. Protestant colonizers came from Great Britain to Ireland in order to take over the land of the local Catholic population. Initially settling in the north of the island, the settlers gradually travelled south.12 Thus, two populations from a different ethnic, religious and cultural background confronted each other. Ireland became a part of the UK in 1801. Only after the foundation of the Republic of Ireland in 1948, the south of the island became an independent county. Mostly Protestant, the north remained a part of the UK.13

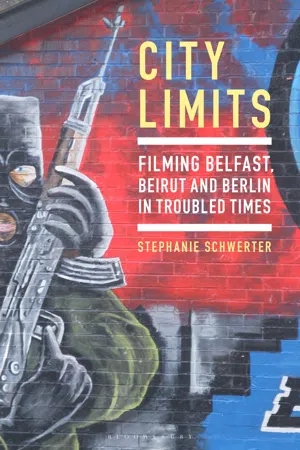

After 1948, the relationship of the two ethno-religious communities deteriorated in Northern Ireland due to the discrimination of the Catholic population concerning employment, housing and the right to vote.14 Violent confrontations between the two groups broke out in 1968, marking the beginning of the Northern Irish conflict, which in the Anglophone world is commonly, somewhat euphemistically, referred to as ‘the Troubles’. As both warring factions did not feel sufficiently protected by the British army and the local police force – the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) – a number of paramilitary organizations formed on both sides. Among the Catholic organizations counted the Irish Republican Army (IRA), the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA), the Real Irish Republican Army (RIRA), Continuity Irish Republican Army (CIRA) and Direct Actions Against Drugs (DAAD). To the Protestant organizations belonged, among others, the Ulster Defence Association (UDA), the Ulster Freedom Fighters (UFF), the Red Hand Commando (RHC), the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and the Loyalist Volunteer Force (LVF).15 Even if most of them officially disbanded and have been at peace since 2005, their splinter groups are still involved in occasional sectarian crimes.16 The acronyms of the paramilitary organizations remain visible on the walls of Belfast’s working-class areas, functioning as boundary markers, which designate the territory of the respective communities. The historian Claire Mitchell explains that the Troubles are not to be seen as ‘a holy war’, but a conflict generated by multiple factors such as ethnicity and inequality, with religion remaining one of the central dimensions of social difference.17 In the same vein, the sociologist Colin Coulter argues that even if the Northern Irish conflict is not about the Bible, religious belief and practice have ‘served to promote those secular identities and disputes that form the basis of the “Northern Ireland problem”’.18 Scholars disagree about the date of the end of the Troubles. While some see the Good Friday Agreement concluded in 1998 as the event ending the tensions, others argue that the Troubles were over only in 2007 with the instauration of a joint government in which Catholic and Protestant were equally present.19

During the Northern Irish conflict, Belfast became the epicentre of political violence. Forty-one per cent of the violent clashes between the two communities happened in and around Belfast. Among the bombings, 70 per cent were aimed at housing in the Belfast urban area. Attacks on shops, offices, industrial and commercial premises as well as clubs and pubs were also disproportionately concentrated in Belfast.20 Today, the city still remains divided into numerous Catholic and Protestant sectors. However, ethno-religiously segregated areas are mostly inhabited by the working class.21 Middle-class areas, on the contrary, are more intermixed. Nevertheless, even if territorial segregation is mostly absent in wealthier neighbourhoods, the prevalence of separate schooling systems, separate churches, separate cultural institutions as well as political parties maintains the communal divide.22 Out of fifty-one wards of the city, thirty-five are almost exclusively Protestant or Catholic.23 Including areas such as Ballymacarret, Sydenham, Ballynafeigh and Castlereagh, East Belfast is inhabited up to 88 per cent by the Protestant community. The presence of the Protestant community in the east of the city is historically due to the shipyard Harland and Wolff, which employed mainly Protestant workers.24 Wishing to remain close to their work place, many employees settled in the east...