eBook - ePub

South East Asia Colonial History V2

Paul Kratoska

This is a test

- 418 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

South East Asia Colonial History V2

Paul Kratoska

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The six volumes that make up this set provide an overview of colonialism in South East Asia. The first volume deals with Portuguese, Spanish and Dutch Imperialism before 1800, the second with empire-building during the Nineteenth Century, and the third with the imperial heyday in the early Twentieth Century. The remaining volumes are devoted to the decline of empire, covering nationalism and the Japanese challenge to the Western presence in the region, and the transition to independence. The authors whose works are anthologised include both official participants, and scholars who wrote about events from a more detached perspective. Wherever possible, authors have been chosen who had first-hand experience in the region

Frequently asked questions

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes, you can access South East Asia Colonial History V2 by Paul Kratoska in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & World History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

INTRODUCTION

DOI: 10.4324/9781003101673-2

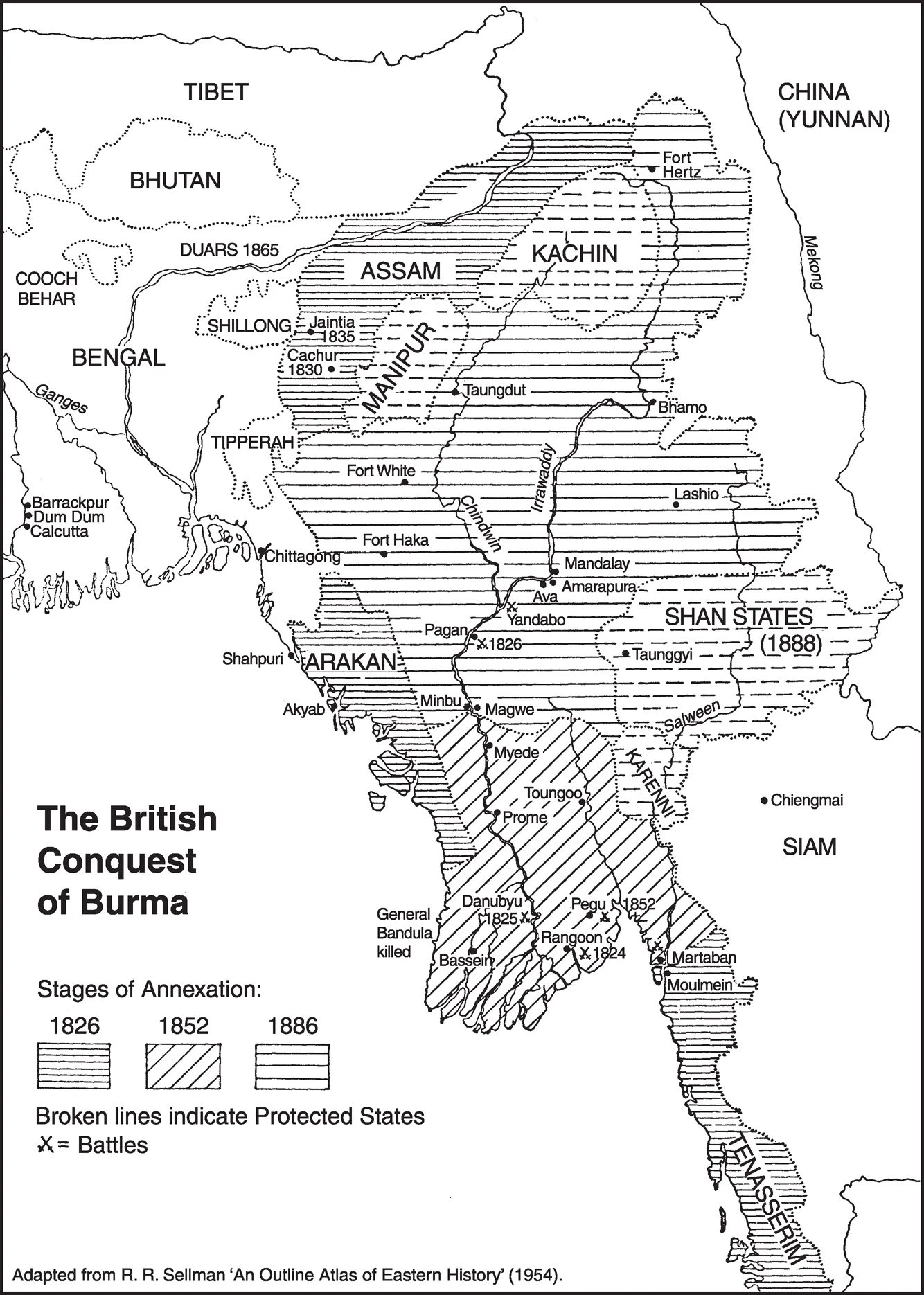

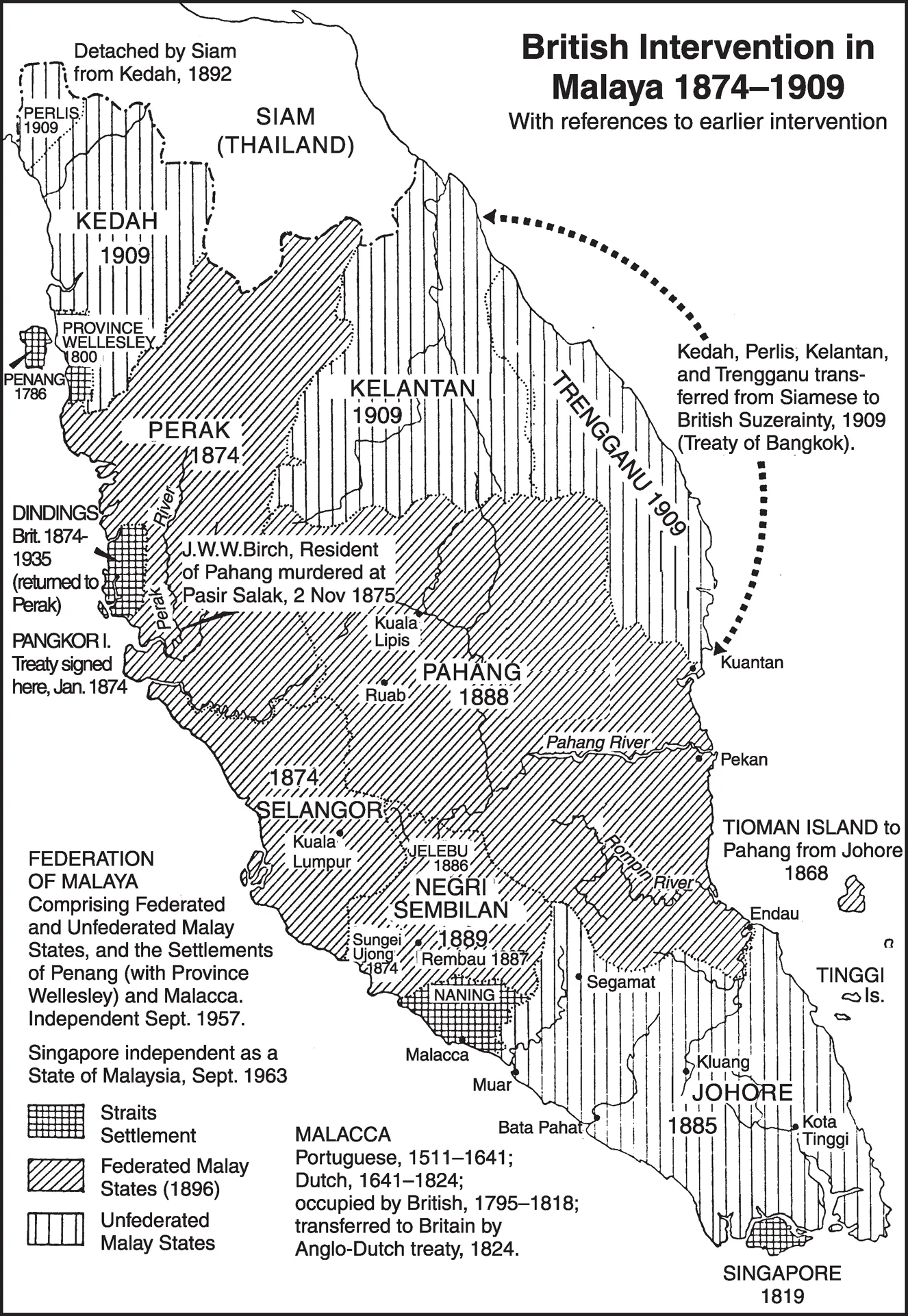

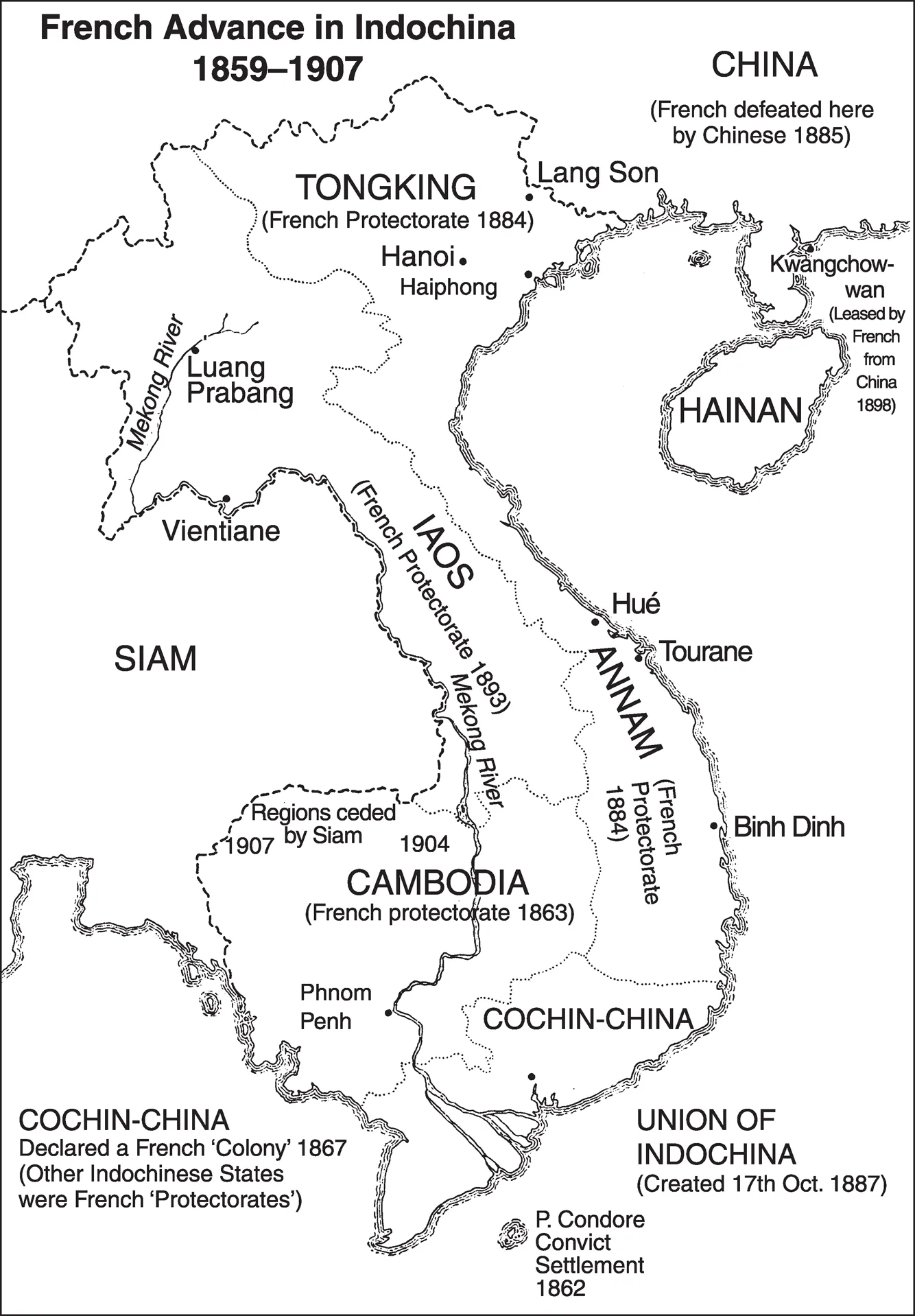

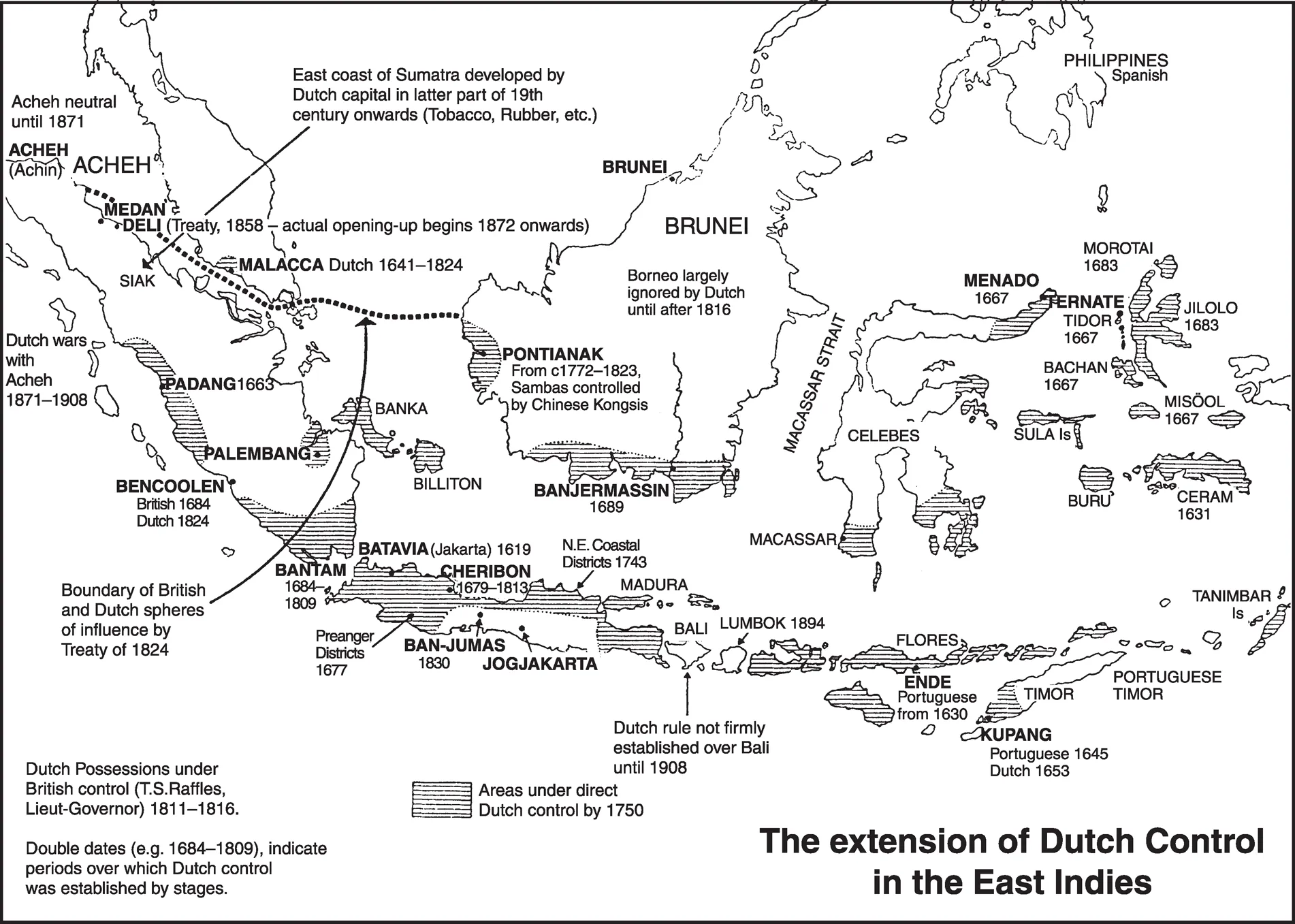

The nineteenth century brought a new wave of colonial expansion to South East Asia, and by the early 1900s the greater part of the region was under some form of Western control. The reasons for this expansion, and the nature of the control exercised, varied considerably. British rule in Malaya grew out of a felt need to forestall the possibility that another power might threaten the trade passing through the Straits of Malacca by acquiring a colony in the Malay Peninsula. British Burma began to take shape as a result of measures taken to defend the eastern frontiers of India, and the process received added impetus from attempts to trade with Burma, and with China through Burma. The hope of gaining access to China through South East Asia also lay behind France’s entry into Vietnam, where the Mekong and Red Rivers appeared to offer prospects for trade with the interior. The Netherlands had maintained a presence in the Indonesian archipelago since the 1600s, but the Dutch now extended their control over a much wider area in order to secure this long-established sphere of influence from imperial adventures on the part of other European powers, and protect Dutch interests from the unrestrained exercise of power by local rulers. At the end of the century, the United States acquired the Philippines in the aftermath of the Spanish–American War, and kept the territory with few clear goals except to prevent it from falling into the hands of other empire-minded powers.

While trade and the protection of borders clearly played a significant role in colonial expansion, some historians have suggested additional explanations. One argument suggests that Western businessmen with a particular interest in colonial territories, or in selling supplies to the military, pushed governments into imperialist adventures. Another calls attention to the activities of ‘men on the spot’ who went beyond the stated wishes of their home governments in acquiring territories or making treaty commitments. Examples of both certainly can be found in South East Asia. Private interests preceded their governments into a number of areas, notably the east coast of Sumatra and the Malay states. And Sir Andrew Clarke arguably exceeded his instructions when he intervened in the affairs of the Malay states, while the French advance in Laos was an almost single-handed effort on the part of Auguste Pavie.

Imperialist expansion involved substantial risks and uncertain outcomes. In itself, expansion was likely to require military action to achieve control and carry out ‘pacification’, and further armed force might be needed to suppress future rebellions or repel an outside attack. The strength of the armies at the disposal of colonial authorities was less than they wished others to believe, and military actions needed to be decisive because defeats were likely to embolden further resistance. Having suffered a setback in one of the British Empire’s least significant military conflicts, at a place near Melaka called Naning, British officials in Bengal sent overwhelming force into the area, noting that any sign of weakness might inspire additional challenges to British authority: ‘Worthless as the object is, we cannot recede without loss of character, and are now bound to subjugate the rebel of Naning coûte qu’il coûte.’1 ‘Cost what it will’, and the costs could be high. Moreover, colonial governments had to meet at least part of these expenses from local revenues. They also had to cover basic administrative costs such as salaries for the civil service, police and judiciary, as well as expenditure for developing physical infrastructure such as public buildings, transport, communications facilities and ports. Finally, they had to deal with a wide range of domestic issues – marriage and divorce and inheritance, petty disputes and minor infractions of the law, and many other matters – that involved financial outlays and gave little or no return.

In contrast with earlier practice, when the Iberian governments and the private, profit-seeking East India Companies exercised sovereign power over overseas territories, colonial administrations now detached themselves from direct economic control and pursued liberal, laissez-faire policies. To raise revenues, they taxed land, imports and exports, prostitution, and non-essentials such as liquor, tobacco and opium. In newly colonized areas the returns were modest, and because home governments expected colonies not to become a drain on the public purse, revenues went to a carefully circumscribed range of activities seen as the proper tasks of government. In the nineteenth century these consisted of little more than defence, law and order, the operation of a court system, tax collection and the provision and maintenance of basic infrastructure. Given that intervention took place in areas of unproven worth, it is somewhat surprising that Western governments showed any enthusiasm at all for colonial adventures.

* * *

This volume begins with an overview of imperialism that compares Britain, France and the Netherlands as colonial powers. The following sections outline details of the process of expansion in the Netherlands Indies, Burma, the Malay Peninsula, Borneo, Indochina and the Philippines. With the exception of John S. Furnivall, who served in the Indian Civil Service in Burma, and Charles Crosthwaite, the authors write as academics, and draw on archival research undertaken long after the events they describe. Crosthwaite, in his capacity as Chief Commissioner of Burma, was head of the civil administration following the final stage of the British conquest and oversaw the pacification campaign there.

Note

- Bengal Secret and Political Consultations, vol. 363, No. 74 of 25 Nov. 1831: Minute by Sir Charles T. Metcalfe, 5 Nov. 1831.

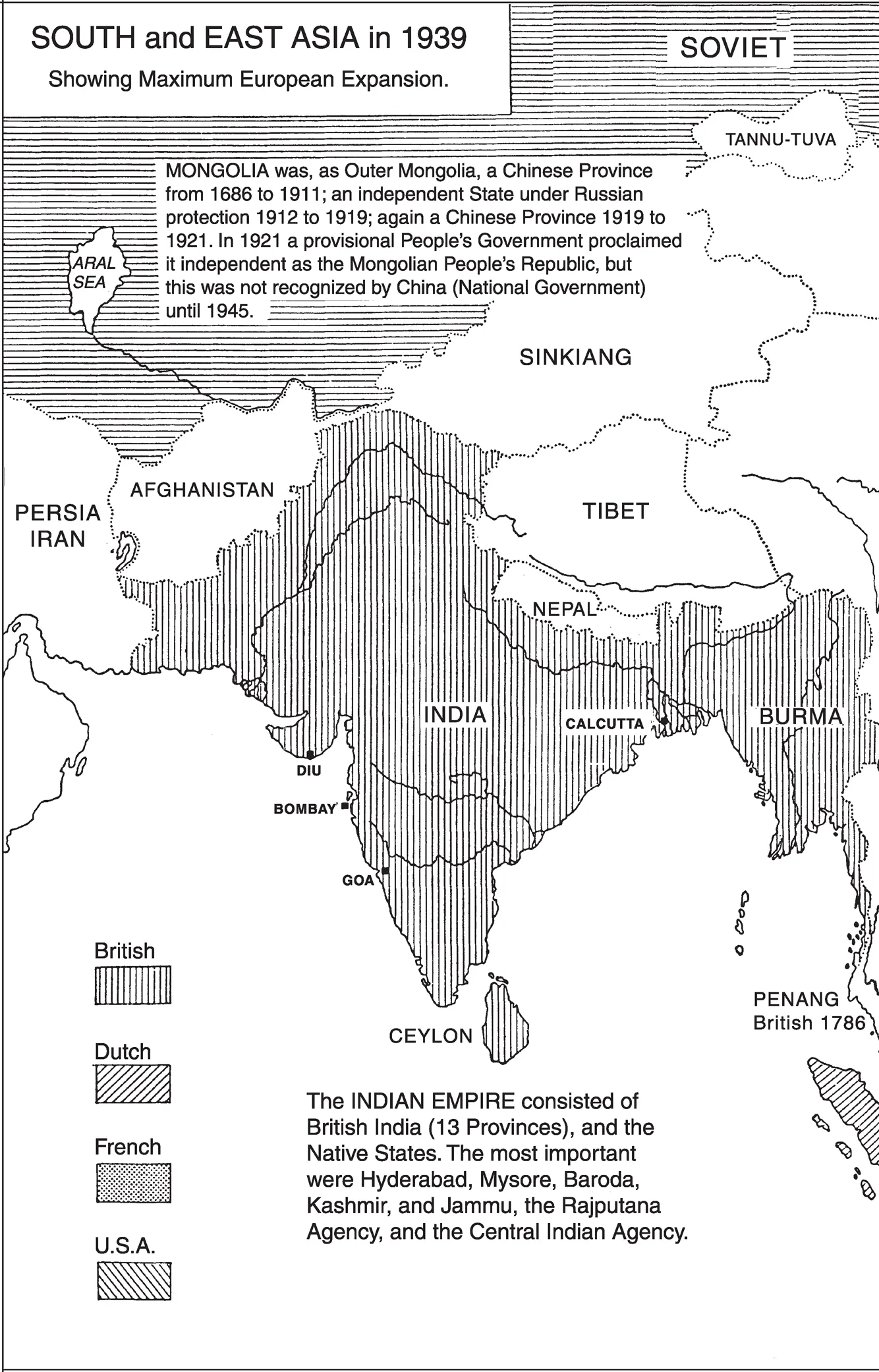

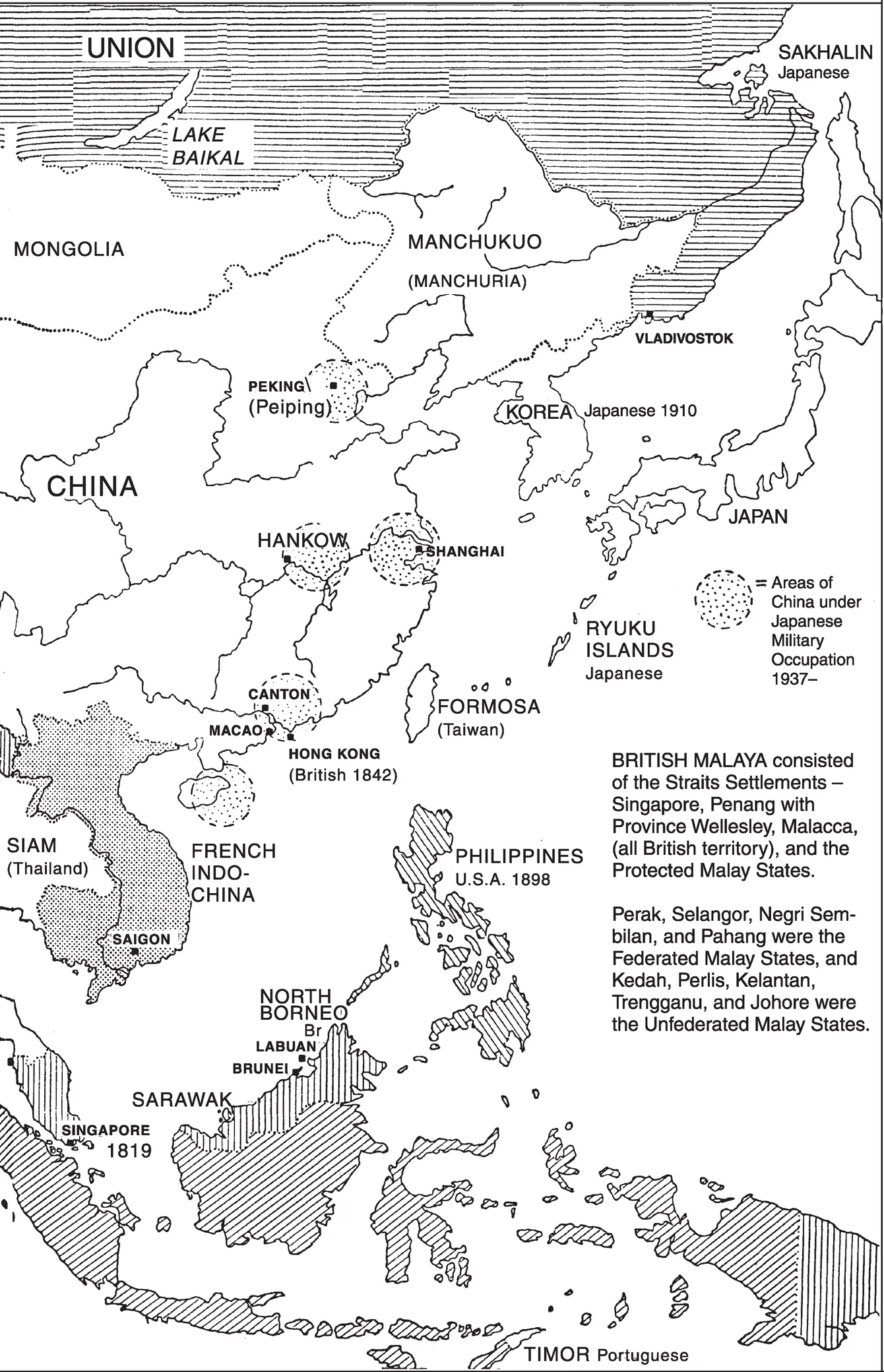

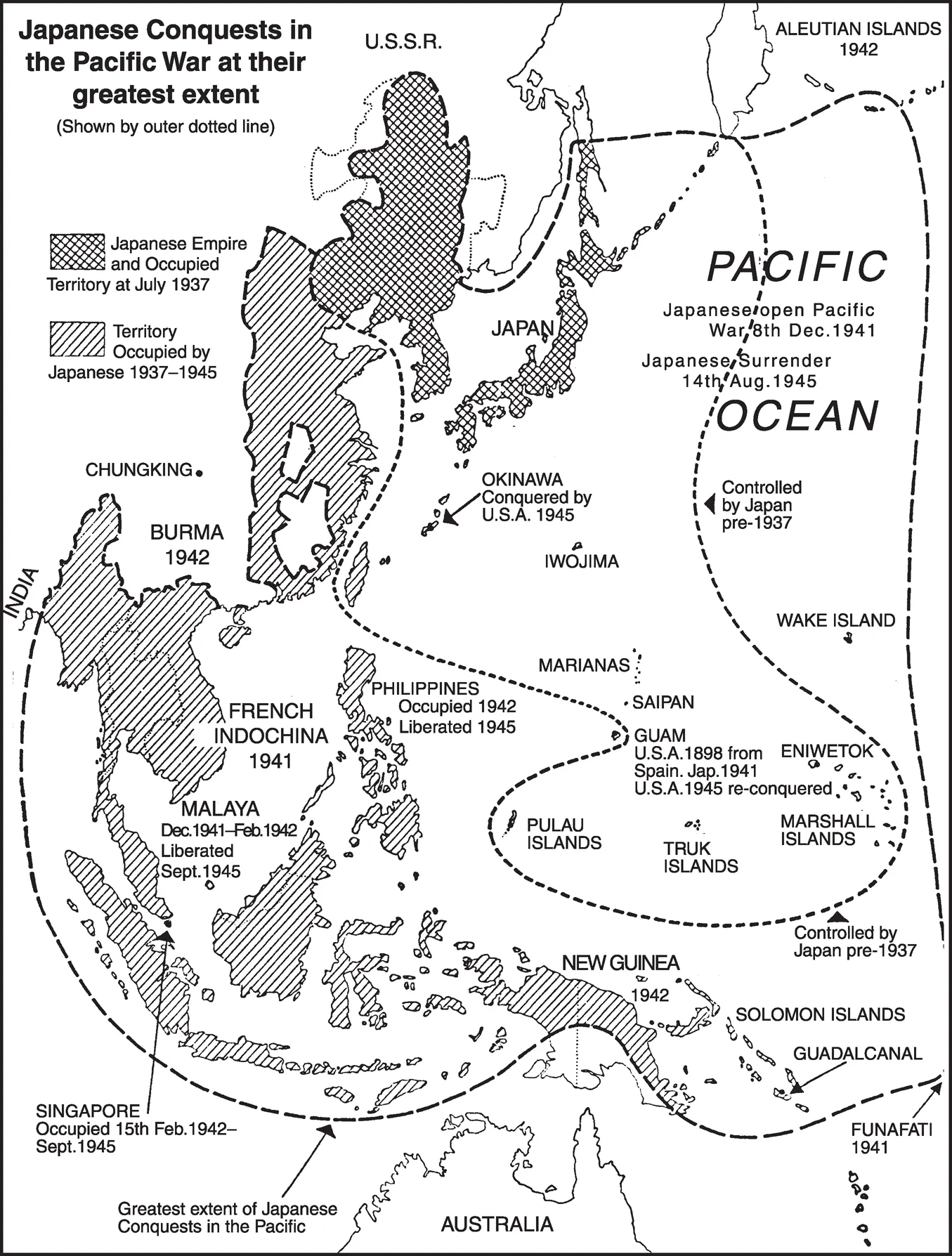

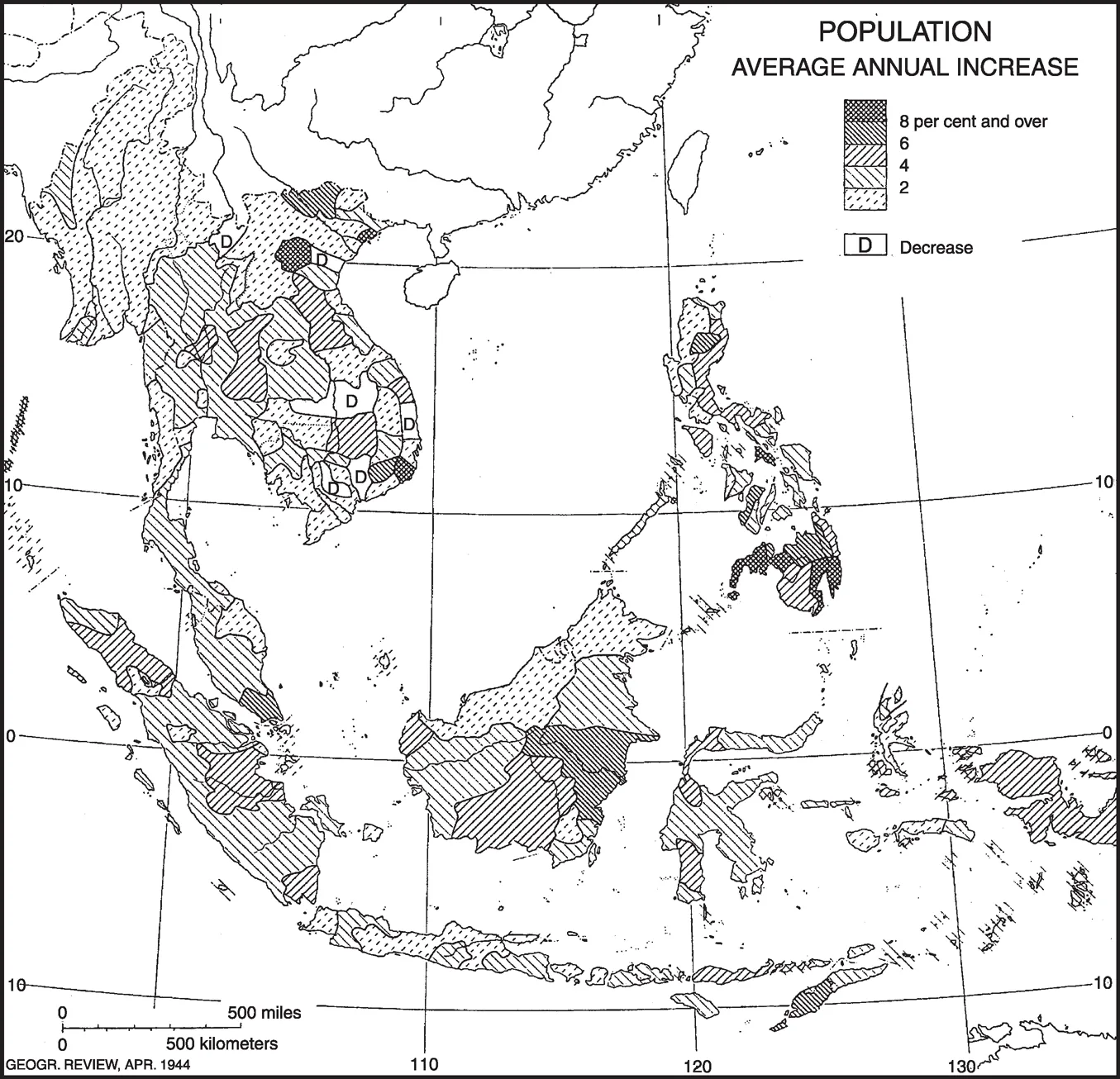

14 MAPS OF SOUTH AND EAST ASIA SINCE 1800

DOI: 10.4324/9781003101673-4

Source: Victor Purcell, South and East Asia since 1800, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press (1965), pp. 35, 49, 65, 104, 116–17, 181.

15 DIVERSITY AND UNITY IN SOUTH EAST ASIA*

DOI: 10.4324/9781003101673-5

Source: The Geographical Review 34(2) (1944): 176–195.

The first half of the 1940’s may prove to be the most momentous period in the history of South East Asia. At the beginning of this decade the lands between China, India, and Australia were, with the exception of the buffer state Thailand, under the direct control of Western nations. Then, in a few months, the 150 million inhabitants of this region were brought under the rule of Japan. Will the expulsion of the Japanese mean a full turn of the wheel of fortune, a return to the situation of 1940? Obviously not; the war has brought such changes in economic, cultural, and political relations and mental attitudes, in the East as well as in the West, that a return to the status quo of prewar years is not only undesirable but impossible.

The colonial question is therefore of greater importance than ever. It is perhaps to be expected that the discussions should center on the subject of political independence, but it is unfortunate that this topic proves so absorbing that little attention is being devoted to equally important economic and social issues. The anticolonial tradition in American history naturally expresses itself in a strong emotional protest against the existence of dependent areas. This attitude can be a powerful lever for progress if it is understood that we are dealing here not with a fortuitous and immoral political relationship but with a deep-rooted cultural and economic complex. The colonial relation is essentially one form of the acculturation process, and as such it is a transitory phase. It was as a dependency of Rome that Western Europe was “exploited,” but also enriched, by the more advanced Mediterranean civilization. In time it threw off the Roman yoke, and eventually it surpassed the old Empire.

South East Asia is now in the stage of “imperial devolution.” The preoccupation with the political aspect of this process obscures, however, the problem in its totality. If one looks at Thailand or at some of the republics of tropical America, it is plain that for the masses a higher standard of living and more democratic procedures do not automatically result from political sovereignty. The Philippine commonwealth, while moving rapidly to political independence, has remained economically dependent on the United States. In the other parts of South East Asia prosperity was not based so overwhelmingly on the right of free access to one market, but collectively these lands were in the same position to the Western countries as the Philippines were to the United States. Japan now grants “independence” generously all over South East Asia, but at the same time it insists on a “co-prosperity sphere” in which, obviously, it will rule while the native peoples will remain the hewers of wood and drawers of water. In turn the Western nations attempt to counteract Japanese propaganda strategy by also making political promises. Thus we may anticipate the strange phenomenon that after the defeat of Japan the ambition of the native peoples for political freedom will be stronger than ever but their economic dependence on the Western nations will be the same, if not greater, than before. This divergence of political ideals and economic realities will be the most baffling problem of postwar tropical Asia.

A one-sided approach, focusing on political doctrines, must inevitably lead to disillusionment. The peoples of the liberated countries will discover that independence has not diminished the need for markets, capital, and trained personnel and that it has not solved the problem of security. And the American people, once again, will be dismayed by the persistence of evils that were supposed to disappear when this war for freedom had been won.

It is often assumed that independent sovereignty for all peoples must be the ultimate aim of a just world order. Yet the Soviet Union, with its great variety of peoples, shows a markedly different, and apparently satisfactory, solution on the basis of equal partnership. We cannot a priori rule out the possibility that some peoples of South East Asia may prefer a similar interdependent relationship. However, whether the future is to be one of equal partnership or of independence, there must be a period of preparation before such adult status can be attained. The roads to this goal as well as the time required to reach it will differ for different peoples, depending as much on their social-economic structure as on their political cohesion.

These considerations are all too often forgotten in the oratorical demands for freedom now and everywhere. Modern means of communication have made the earth a unity, but they have not created uniformity. The recent discovery that the earth is “global” does not change the fact that peoples are first of all a part of their local culture pattern, each with its own interdependent relationships of man to man and man to nature, its own traditions, institutions, and ways of making a living. Terms such as “democracy,” “self-determination,” and “independence” receive their meaning from local experience, not from global charters. Instead of offering universal, ready-made schemes that are likely to prove misfits, we must analyze the specific regional problems and lay plans accordingly.

Regional diversity in South East Asia

In the last year or so various plans have been advanced to fuse the former dependencies into one or two political units administered or supervised by an international authority or mandatory power until the countries are ready for complete self-rule.1 Quite aside from other difficulties, such schemes do not take sufficient account of the diversity of South East Asia.

The natural environment shows a great variety of conditions. The dominant fact is the fragmentation of the lowlands by either seas or mountains. Great plains at one time existed where we now find the drowned Sunda and Sahul shelves, but the present plains beyond the amphibious coastal swamps are relatively small. Within the lowlands there are strong contrasts in soil fertility.2 The best soils are those derived from volcanic deposits. These are found along the inner curve of the great southern island arc, from Sumatra east to the “fishhook” around the Banda Sea, and in the northern arc (part of the East Asiatic island festoons) running from Formosa through the Philippine Islands south to northern Celebes and Halmahera (Fig. 1).

Figure 1 Orientation map. The 100-meter contour line (omitted for the smaller islands) brings out the small extent of lowland areas in South East Asia. The 200-meter bathymetric line indicates the extent of the continental shelves. Tectonic movements in these shelves have subsided; the uplands are dominated by erosional activity, and relatively extensive coastal plains have resulted from deposition. In the zone between the Sunda shelf on the west and the Sahul shelf on the east, and continued to the north in the Philippines, recent and continuing vertical movements are reflected in the mountainous island chains, separated by deep sea basins. The distribution of volcanoes is based on W. D. Smith: The Philippine Islands (Handbuch der regionalen Geologie, No. 3), Heidelberg, 1910, pp. 13 ff. (map of Philippine Islands on p. 14); E von Wolff; Der Vulkanismus, Vol. 2, Part I, Stuttgart, 1923, pp. 159 ff. (Fig. 12 is an adaptation of W. D. Smith’s map); Atlas van Tropisch Nederland, 1938, Sheet 5; L. M. R. Rutten: Voordrachten over de geologie van Nederlandsch Oost-India, Groningen, 1927. The large number of volcanoes in northern Celebes necessitated the use of smaller symbols in that area.

In March, 1941, the Japanese government, acting as “mediator” in the Thai-Indochinese war, allotted parts of Laos and Cambodia (1 and 2) to Thailand. The other boundary changes were announced by the Japanese radio early in July (New York Times, July 6, 1943). Parts of the Shan States, of which Kentung and MOng Pan were mentioned by name, were added to Thailand (3). Also, the four northern Malay States, Perlis and Kedah (4) and Kelantan and Trengganu (5), were “ceded” to Thailand.

Areas marked 2 have a less pronounced dry season and are transitional to the areas with “year-round” rainfall. Java, for example, is under the influence of the Asiatic (N.W.) mo...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Empire-Building During The Nineteenth Century

- Introduction

- The Dutch

- The British In Burma

- The British in the Malay Peninsula

- The British In Borneo

- The Americans In The Philippines