![]()

CHAPTER 1

Triangular Relations and the Pacific War

ON THE EVENING of April 13, 1941, Stalin hosted Japan’s foreign minister, Yosuke Matsuoka, at a banquet in the Kremlin to celebrate the Neutrality Pact that had been signed that afternoon. Jubilant and quite drunk, Matsuoka pledged: “The treaty has been made. I do not lie. If I lie, my head shall be yours. If you lie, be sure I will come for your head.” Stalin replied: “My head is important to my country. So is yours to your country. Let’s take care to keep both our heads on our shoulders.” Then Stalin told Matsuoka: “You are an Asiatic. So am I.” “We’re all Asiatics,” Matsuoka chimed in. “Let us drink to the Asiatics!”

The two men met again the following day. Stalin made a rare appearance at Yaroslavl Station to bid farewell to Matsuoka. He embraced and kissed the Japanese foreign minister and saw to it that the scene was photographed. Stalin carefully staged his appearance to demonstrate—as much to the Japanese as to the German ambassador also present at the railway station—the importance of the Neutrality Pact.1

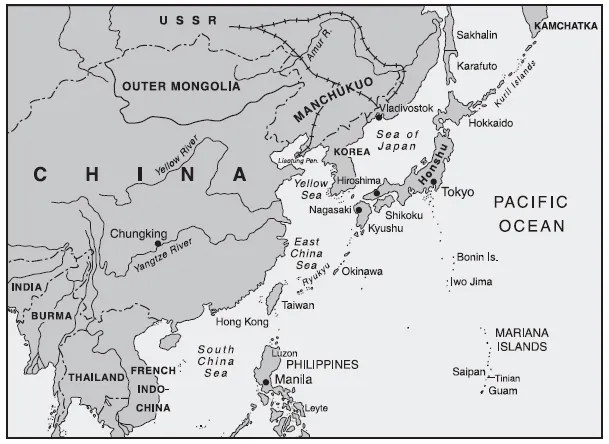

A quick glance at the tortured history of Russo-Japanese relations since the late nineteenth century is sufficient to appreciate the uniqueness of this ostentatious display of friendship. But it is also important to bear in mind that two other powers, the United States and China, were closely intertwined with Russo-Japanese affairs. Exploiting China’s weakness, Russia acquired enormous territories north of the Amur and west of the Ussuri in the middle of the nineteenth century. Russia founded the port city of Vladivostok in 1860 as its gate to the Pacific Ocean. Its next ambition was to extend its influence into Manchuria and Korea. But there, Russia encountered Japan, a formidable rival who, having embarked on modernization after 1868, began its own imperialist expansion into its neighbors’ territory. Japan’s aggressive policy toward Korea soon enraged China, the nominal suzerain of the hermit kingdom, and the two Asian countries went to war in 1894–1895. Japan defeated China, which was obliged to cede to the victor Taiwan, the Pescadores Islands, and the Liaotung Peninsula in Manchuria, and to recognize Korea’s independence. Japan had now acquired a foothold into the Asian continent. (See Map 1.)

Alarmed by Japan’s intrusion into Asia, Russia persuaded Germany and France to force the Japanese to abandon the newly acquired Liaotung Peninsula. In addition, in the 1890s Russia began to build the Chinese Eastern Railway through Manchuria to Vladivostok. Japan was further humiliated when in 1898 Russia acquired the lease for the Liaotung Peninsula and the right to construct the South Manchurian Railway connecting the Eastern Chinese Railway to the warm-water port of Dairen and the naval fortress of Port Arthur. Russia and Japan were on a collision course.

When the Chinese revolted against foreign powers in the Boxer Uprising in 1900, Japan and Russia sent a large contingent of expeditionary forces. To Japan’s alarm, Russia not only refused to withdraw its forces after the uprising was quelled but also began sending significant reinforcements over the Trans-Siberian Railway. In 1902, as tension between Russia and Japan intensified, Japan concluded the Anglo-Japanese Alliance, thereby securing a powerful ally. In February 1904 Japan broke off relations with Russia and launched a surprise attack on the Russian fleet in Port Arthur two days before it declared war against Russia. The Japanese laid siege to Port Arthur, which fell in January 1905. The Japanese Army crossed the Yalu into Manchuria and captured Mukden in March. Russia pinned its last hope on the Baltic fleet, which sailed all the way across the world to attack Japan. But the Japanese Navy, which waited in the Straits of Tsushima, annihilated the Russian fleet in a one-day battle. Russia lost the war. The Portsmouth Treaty, mediated by President Theodore Roosevelt in 1905, granted to Japan southern Sakhalin and the South Manchurian Railway as far north as Changchun and Liaotung Peninsula. The Japanese Empire gradually turned Manchuria into a virtual colony by sending Japanese settlers, who displaced Chinese villagers. Once this colonial outpost was created, it had to be protected from Russian encroachments. The Japanese troops stationed in Manchuria became the Kwantung Army in 1919. (See Map 1.)

Map 1. Japan at War, 1945

Defeat in the Russo-Japanese war delivered a profound blow to Russia.2 Not only did it acquire the dubious distinction of being the first European great power to suffer defeat at the hands of a non-European power, but it also was compelled to cede to Japan southern Sakhalin, an integral part of its territory. Moreover, Russia lost the strategically important city of Dairen and Port Arthur. This humiliation lived well beyond the Russian Revolution.

After the Russo-Japanese War, however, Russia and Japan quickly reached rapprochement by concluding three conventions in 1907, 1910, and 1912, which divided their respective spheres of influence. Whereas Outer Mongolia became Russia’s protectorate, Japan annexed Korea. Manchuria was divided in half, the southern half under Japan’s sphere of influence and the northern half under Russia’s. These conventions were also designed to exclude from Manchuria other Western powers, especially the United States, which was making aggressive attempts to expand its influence through commercial and financial deals in the name of the open door policy.

World War I gave the Japanese an opportunity to expand their territorial ambition in China. Taking advantage of the European powers’ preoccupation with the war in Europe, the Japanese sent troops to Tsingtao to repulse the Germans and imposed the infamous Twenty-one Demands on China. All the major powers protested against Japan’s brazen opportunism. Only Russia refrained from joining the chorus of protest in the hope that its silence would earn the gratitude of Japan and prevent it from infringing on Russia’s territory in Manchuria. In 1916, Russia and Japan concluded an alliance whereby they pledged to support each other if a third party were to threaten their respective spheres of influence.

The Russian Revolution and the civil war, however, exacerbated Soviet-Japanese relations. Together with the United States, Japan sent its expeditionary forces into the Soviet Far East to assist anti-Communist forces. But Japan’s mission was avowedly more territorial than anti-Communist; Japan intended not only to invade northern Manchuria but also to extend its reach far into Siberia and northern Sakhalin. Japan’s “Siberian intervention” resulted in strong feelings of hostility on the part of the Russians toward the Japanese and validated the Soviets’ suspicion that Japan was always ready to pounce on Russia.

Just as the Versailles Treaty was the foundation on which the post–World War I order was constructed in Europe, the Washington Treaty system that resulted from the Washington Conference in 1921–1922 was the basic framework of Asian international relations. Japan agreed to adhere, together with the United States and Britain, to naval disarmament and concluded the Nine-Power Agreement, which guaranteed China’s independence and territorial integrity. The Soviet Union was excluded from both the Versailles Treaty and the Washington Treaties. Left isolated, the Soviet Union had to fend off Japan’s expansion alone. In accordance with the agreement reached between the Far Eastern Republic, a buffer state created by the Soviet Union, and the Japanese government, Japan finally withdrew its troops from the Soviet Union, except for northern Sakhalin. Not feeling completely comfortable with international cooperation with Western powers, and facing mounting domestic criticism against the cost of continuing the intervention, Japan also found it convenient to reach rapprochement with the Soviet Union in order to settle the new demarcation between their respective spheres of influence in Manchuria. Both countries restored diplomatic relations in the Basic Convention of 1925. Japan finally withdrew its troops from northern Sakhalin in exchange for oil concessions.

Japan Invades Manchuria

Japan’s invasion of Manchuria in 1931 marked a new era in international relations in the Far East. In 1932, Japan created the puppet state of Manchukuo. In 1933 it withdrew from the League of Nations. In 1934 it annulled the Washington Naval Disarmament Treaty. Despite Japan’s brazen aggression and open challenge to the Washington system, however, the reaction of Western powers was muted. The British government was reluctant to challenge Japan, as it was not completely averse to the possibility of a Soviet-Japanese war. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, inaugurated into office in 1933, was initially preoccupied with domestic problems and lacked a clear vision for a new international system in the Far East.3

Japan’s invasion and annexation of Manchuria posed a serious threat to the Soviet Union. Still isolated diplomatically, the Soviet government had to devise ways to fend off the constant threat coming from Japan, which was under the increasing control of the military. Its first line of defense was appeasement. During the invasion, the Soviets kept strict neutrality. When Japan rejected the Soviets’ repeated attempts to conclude a non-aggression pact, the Soviet government negotiated with Japan for the sale of the Chinese Eastern Railway. The deal went through in 1935.

Between 1933 and 1937 international relations in the Far East were marked by uncertainty. The Japanese government under the leadership of the foreign minister and later prime minister Koki Hirota attempted to establish a new international order that recognized the gains Japan had obtained from its aggression. The Nationalist government in China was divided over peace with Japan: Chiang Kai-shek sided with the pro-peace faction against the pro-war faction headed by his brother-in-law, T. V. Soong. To complicate the matter, Nazi Germany maintained close relations with the Nationalist government in China during that period and even provided it with substantial military aid and advisers. The British government vacillated between appeasement and confrontation with Japan. The Americans, though more alarmed by Japan’s expansionism than the British, remained largely passive.

Facing the danger of the Japanese military threat in the East and the rise of Nazi Germany in the West, the Kremlin adopted a new foreign policy designed to seek collective security with Western powers. The Soviet Union gained the diplomatic recognition of the United States in 1933 and joined the League of Nations in 1934. In 1935 the Comintern, the headquarters of the Moscow-led international Communist movement, adopted a new policy calling for the formation of a popular front against fascism. Nevertheless, U.S. recognition of the Soviet Union did not immediately lead to a meaningful coalition with Western powers against the Japanese threat. The continuing dispute over payment of debts that the Bolshevik government had canceled after the Russian Revolution became the insurmountable obstacle to further improvement in relations with the United States. The British government under Exchequer Neville Chamberlain and Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin preferred instead to establish “permanent friendly relations” with Japan by recognizing Manchukuo. This situation left the Soviet Union with one option to guard against possible Japanese aggression: to rely on its own military strength and demonstrate its determination in border incidents.

The Soviet military buildup in the Far East began in earnest. In 1931, the Kwantung Army outnumbered the Red Army by a large margin, but by 1939 the situation was reversed. In 1932 the Pacific Fleet was created. The double-tracking of the Trans-Siberian Railway was completed in 1937. The Soviets also began building fortifications along the Manchurian border and the Maritime Province.

While the Soviets were quickly fortifying the Manchurian border, Japanese militants were loudly advocating war against the Soviet Union. General Sadao Araki, the army minister from 1931 to 1934, repeated his conviction that war against the Soviet Union was Japan’s national mission. But this policy met with the opposition of the navy, which preferred war against the United States and Britain. In August 1936, the Japanese Government and the Imperial General Headquarters adopted three basic principles for Japan’s foreign policy: to maintain Japan’s position in the Asian continent; to prevent Soviet expansion in the continent; and to advance to the south. The prototype of Japan’s direction in the Pacific War was formulated. And yet Japan remained decidedly anti-Soviet. In 1936 it concluded the anti-Comintern Pact with Germany. Its secret protocol stipulated that if one party went to war with the Soviet Union, the other party was obligated to remain neutral. This pact, which was concluded one month after the formation of the German-Italian Axis, meant that Japan took the decisive step toward siding with the Axis powers.

The second Sino-Japanese War, in July 1937, forced the major powers to abandon their past policy of non-intervention. As Japan quickly expanded the war in China, President Roosevelt made a speech in Chicago in October stressing the need to “quarantine” those who were spreading “the epidemic of world lawlessness.” This was Roosevelt’s first signal that the United States would abandon isolationism. In November, Japanese troops pursued the retreating Nationalist forces to Nanking and committed the Nanking massacre. This brutal action invited international outcry and contributed further to the isolation of Japan in world public opinion. In 1938, Roosevelt initiated the U.S.–British military cooperation for joint operations against Japan, and moved the major portion of the U.S. fleet to the Pacific. He also approved a loan to China to support the Nationalist government’s resistance to Japanese aggression. The United States was emerging as the major power to block Japan’s military expansion. While the United States was asserting its strong stand against Japan, Hitler abandoned Germany’s long-standing assistance to China and recognized Manchukuo. The clear line between the Axis powers and Western liberal allies was now clearly drawn. The question was, Which side would the Soviet Union take?

The Sino-Japanese War was a godsend for the Soviet Union. The more the Japanese became bogged down in the quagmire of the war in China, the less likely they were to invade the Soviet Union. In the initial phase of the Sino-Japanese War, the Soviets were China’s most reliable ally; they concluded a non-aggression pact with the Nationalist government and shipped weapons, planes, and tanks to China to help the Chinese resist Japan’s aggression.

From 1937 on, the Soviets became more aggressive in responding to border skirmishes with the use of force. In 1938 the Soviets and the Japanese clashed in a major border battle at Lake Khasan (Changkufeng) near the Korean border. In 1939 they again clashed in a full-fledged war in Nomonhan (Khalkin Gol) along the Mongolian-Manchukuo border that resulted in a Soviet victory. The defeat had a sobering effect on the Japanese military. Japan’s offensive against the Soviet Union would require careful planning and enormous military buildup along the Soviet borders.

Conclusion of the Neutrality Pact

The outbreak of World War II dictated to both countries the temporary suspension of hostilities for their respective strategic interests. The Munich Conference in 1938 had convinced Stalin that the only way to keep the impending war from being fought on Soviet soil was to conclude the Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact. Despite the pact, however, Nazi-Soviet relations quickly deteriorated by the end of 1940, raising the ominous possibility that the Nazis might invade the Soviet Union. To avoid a war on two fronts, Stalin needed Japan’s neutrality.

The Japanese were shocked to learn of the Non-Aggression Pact. But they very quickly decided to exploit the changing vicissitudes in the international situation, and in 1940 they concluded the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy. Matsuoka declared that the pact was “a military alliance directed against the United States.” Foreign Minister Matsuoka had a grandiose plan to form an anti-Western alliance consisting of Germany, Italy, Japan, and the Soviet Union. For this purpose, he made a grand tour in March and April 1941, visiting Moscow, Berlin, and Rome. While in Moscow, Matsuoka negotiated with Stalin and Viacheslav Molotov to conclude a neutrality pact. But the negotiations were anything but smooth. To conclude the pact, Stalin had to intervene personally and Matsuoka had to pledge to abandon oil concess...