Chapter 1

Stanley Spencer

The Berkshire village of Cookham lies in a crook of the Thames a few miles upstream from Maidenhead and twenty-five miles west of London. In the last years of Queen Victoria’s reign, in winter and spring it was a tranquil place, frequently cut off when the surrounding commons and water meadows flooded. But in summer the river sprang to life, thronging with pleasure seekers in punts, rowing boats, skiffs and paddle steamers. July saw the ancient ceremony of Swan Upping, when the Vintners’ and Dyers’ Companies claimed ownership of the swans between Blackfriars Bridge and Henley, gathering them in to mark their beaks: once for the Vintners, twice for the Dyers, and those left unmarked for the Queen. And in September there was Cookham Regatta, when the village was decorated with flags, and the trees decked with bunting and Chinese lanterns. Brass bands played, and the river filled with all manner of floating vessels.

It was these pleasures of the Thames that Jerome K. Jerome captured in 1889 in his comic novel, Three Men in a Boat:

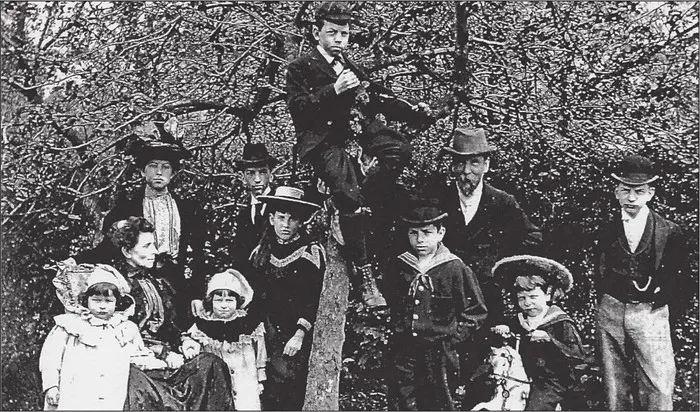

Had Jerome and his friends lingered longer in Cookham, perhaps to gather supplies from the village shop or pause for refreshments at the Old Ship Inn or the Bel and the Dragon Hotel, they would have passed on the High Street two tall, semi-detached Victorian brick villas. Fernlea and Belmont were the homes of two brothers and their families, and had been built by Cookham’s master builder – their father, Julius Spencer. In Cookham, everyone knew everyone else, and many local families were related: courtships and romances started as early as the village school, and Julius’s grandchildren could claim over seventy relatives in the neighbourhood.

Mirror images of each other, Fernlea and Belmont could be distinguished by the brass plate on the former’s front gate: ‘W. Spencer: Professor of Piano’. In the year Jerome’s novel was published William Spencer was forty-four years old and, as local church organist and resident music teacher, was a familiar sight around the village, out in all weather on his lady’s bicycle, music case slung over the handlebars, reciting aloud the works of his adored hero, the art critic and social reformer John Ruskin. William Spencer was an excitable, pious man with a sense of wonder that expressed itself in his fondness for music, poetry and astronomy, and in his intimate observations of nature: ‘I crossed London Bridge on Tuesday and could have stood for hours watching the flight of the seagulls – surely the acme of graceful motion’, he told one of his sons. ‘And yet the people passed by without a glance’.2

‘Par’ Spencer’s family was large, talented and musical; his greatest ambition was the success of his eldest son and namesake. A child prodigy, William junior could play preludes and fugues from memory on the family piano. Even before he could reach the pedals he was performing before the Duke of Westminster at Cliveden, the large country house across the Thames. Guests included the Prince of Wales (the future King Edward VII), who presented the young virtuoso with a piano of his own. When he grew older Will progressed to the Royal College of Music in London, and gave evening recitals at Maidenhead, the family dressing up to hear him play. The Spencers were doing well: Par travelled regularly to London to serve as organist at St Jude’s, Whitechapel, and to give piano lessons to wealthy West Enders. There were concerts, servants and a nurse to look after the five children: what one of them later called ‘all the trappings of position’.3

Par did everything he could to further his eldest son’s musical success. In fact, with overbearing Victorian discipline, he did too much. Long hours of endless practice, together with Par’s ban on outdoor sports that might damage his son’s precious fingers, combined to undermine Will’s health, and he suffered a nervous breakdown. But again, only the best would satisfy Par – Will was sent to Thomas Holloway’s ‘Sanatorium for Curable Cases of Mental Disease’ at Virginia Water. This eventually proved too much for Mrs Spencer, however. Seeing that the hospital was nothing more than ‘a club for rich dilettantes with a turn for discussion and a belief that they had been reprieved from facing life outside’,4 she brought Will home to Cookham. Though she had saved her eldest son from a life of idle infirmity, the family’s fortunes were already broken. Financially spent, his ambitions shattered, according to his youngest son, Par Spencer ‘never quite got over the failure of his highest hopes, and buried himself and his disappointment more and more in his books.’5

It was into this ‘confusion of ambitions, high endeavour, disappointments and partial recovery’ that Mar and Par’s last children were delivered.6 Stanley Spencer was born in Cookham on 30 June 1891 and Gilbert in August the following year. With the money for a nanny eaten away by Will’s hospital fees, their teenage sister Annie took charge of the boys. Theirs would be a simple, unrestricted upbringing, as Gilbert later recalled, and the brothers were preciously close. Stanley later remembered how he once hit his younger brother, ‘not very hard’, but ‘Gil bellowed like a bull & then of course I cried. If Gil cried I cried & if I cried Gil cried. Mar comes rushing into the room, “What is it”, “I’ve hit him I have, I hit him I have, oh Gil”, “Oh Stan”, “Oh Gil”, “Oh Stan”.’

And Stanley recalled another time when he and his brother sat in their high chairs: ‘we were talking over things in general when Gil says very mysteriously “Stan, what are Angels?”, “Ow” says I very knowing and wise “Great big white birds wot pecks”. Gil after digesting this peered about for a white bird wot pecks’. His eyes fell on Annie: ‘so Gil outs with it “Is she an Angel?”, “No” says I very contemptibly “Not great big squashed fat things like her”.’7

On wet days the boys made their own entertainment indoors: they had only a few toys — an old jigsaw puzzle, a box of buttons, later some wooden bricks. They cut up pieces of paper to make figures to play with, opened with wonder huge old books of wallpaper samples, inhabiting their private imaginative world. Though they preferred to amuse themselves in the nursery, on fine days their sister took them on meandering walks round the village, which began to fascinate and entrance them. Sneaking into the mysterious garden of some grand old house, climbing trees and ‘swinging high into other lands’, Gilbert would long after recall how ‘the thrill of seeing bits of Cookham cropping up in strange places so unexpectedly never lost its charm for us.’8

As they grew older the brothers swam in the river, played football and cricket on the common, or hid unnoticed in dark corners of the village, watching their little world revolve around them. Their love of Cookham and its varied inhabitants meant everything to them – Gilbert swore that the villagers could be distinguished by the different sounds their shoes made on the road.9 And at the centre of it all was the church, where their brother William performed Bach on the organ – a sound like the joy of angels, said Stanley – and in whose graveyard they played among the tumbling tombstones of Cookham’s ancestral dead.10

Such was their love of home that a visit to another brother in Maidenhead left them miserable. Gilbert thought this fierce love of Cookham was inherited from their father: ‘With so much of his life now in the past, it was all he had to give us, but it was all we needed, or for that matter ever wanted.’11 When Par made £10 from a published edition of his poems (Verses, Grave and Gay), he invested the money in a range of ‘Everyman’ classics and established a lending library in Fernlea’s front room, employing Stan and Gil to paste labels in the books. It was opened to the public with expectant excitement – but nobody came. Such schemes were vivid illustrations of what Gilbert called Par’s ‘odd excitability and lack of control’.12 But he galvanised the young boys with his love of existence: ‘With him, there could be no excuse for idleness’, wrote Gilbert much later. ‘Father lived his life whole, and we too if we wished could follow his example out in the “world” – which for us and for him was still Cookham.’13

Mar was the rock on which the family stood, ‘strong willed and strong minded’, taking everything calmly in her stride – but it was Par the boys kissed goodnight.14 Returning home from London, he brought them presents – one penny ‘Books for the Bairns’: Brer Rabbit, Snow White, Don Quixote, Gulliver’s Travels, Pilgrim’s Progress. After Annie had put them to bed she practised her viola in their room whilst downstairs Par continued his piano lessons. Melodies of Handel, Beethoven, Schubert and Mozart floated up through the house, with occasionally an exasperated cry of criticism from Par: ‘You play the piano like one of your father’s cart horses!’15

This lively family life seemed to provide for everything. Meal times were an animated r...